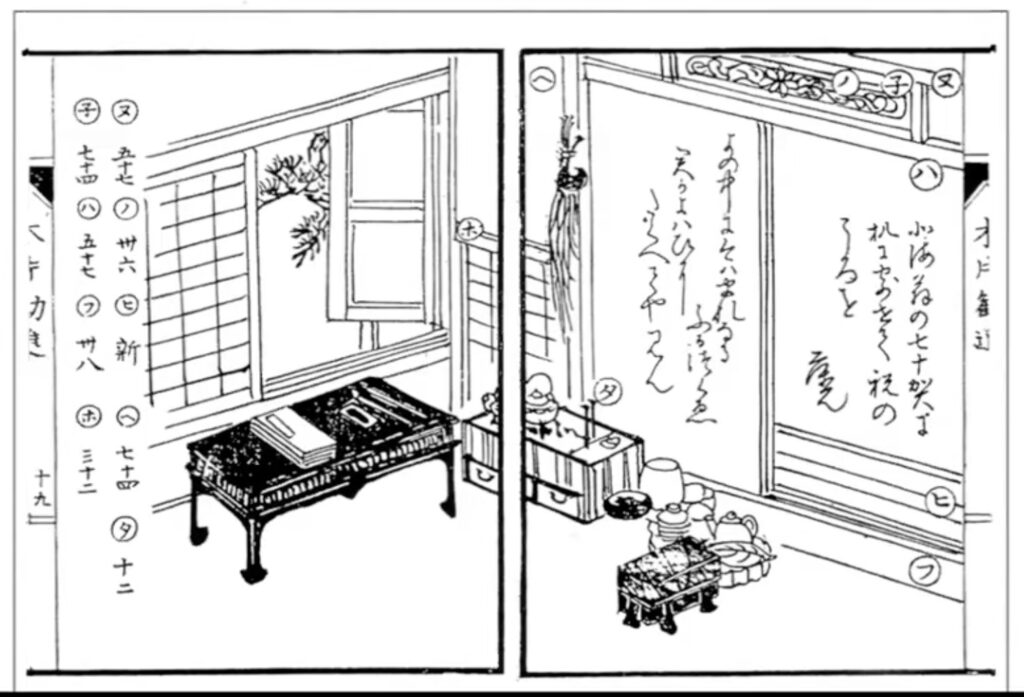

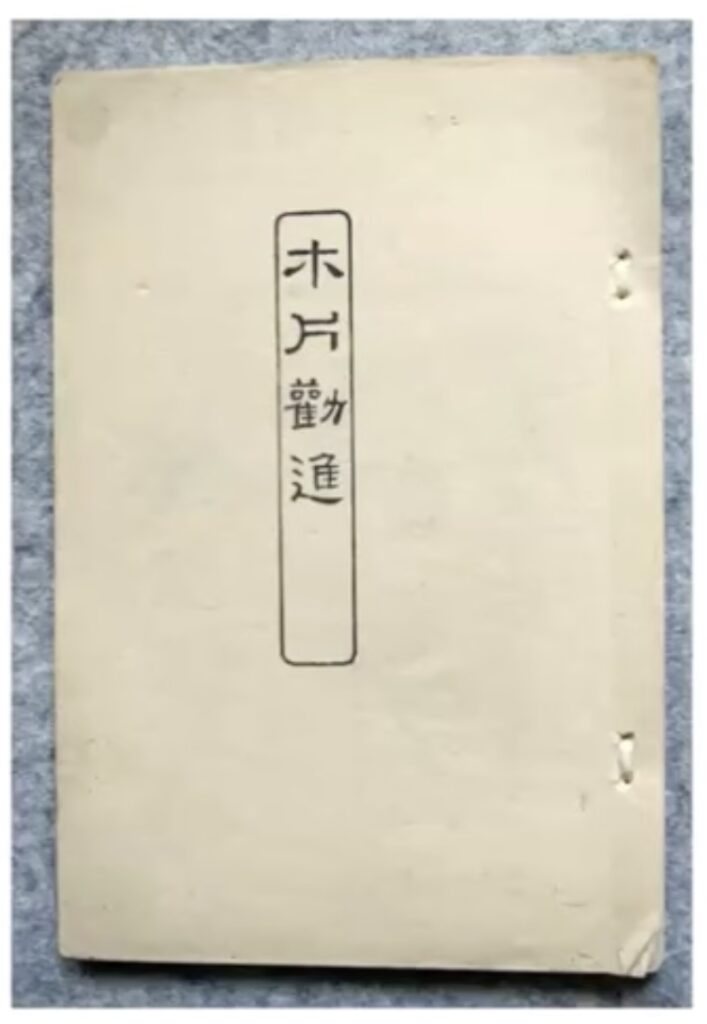

After two decades as an explorer and cartographer, Matsuura Takeshirō, who gave the northern island of Japan its name, Hokkaidō, settled into a second life as an antiquarian. In anticipation of his 70th year (1888), he decided to build a tiny study onto his small house in central Tokyo, and asked his antiquarian colleagues across Japan to each send him a piece of old wood. He called the study the Ichijōjiki ((一畳敷), or One-Mat Room, though it is actually slightly larger than its single tatami mat. Matsuura documented each piece of wood, its source and significance, and its donor, in a tiny, self-published catalogue, Mokuhen Kanjin (木片勧進), which Columbia professor emeritus Henry Smith II translates as, A Solicitation of Wood Scraps.

Smith is certainly the foremost non-Japanese expert on the One-Mat Room, which survived Matsuura’s death, three moves, the Great Kantō Earthquake, and WWII, and is currently on the campus of International Christian University in Tokyo. Smith’s 1993 monograph on the One-Mat Room, for which he visited all 91* sources of wood and other artifacts, is so far impossible to find. But his 2012 essay for Impressions, the journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, “Lessons from the One-Mat Room,” [pdf] is on his webpage. [h/t Steve Forrest via Shannon Mattern for pointing to this article on bluesky]

From Smith’s “Lessons”:

The One-Mat Room (Ichijōjiki) project that he designed to celebrate his seventieth year was essentially a joining of two types of mapping, first of the religious and historical sites from which the pieces of wood had come, and second of his network of friends who donated these “wood scraps.” Each entry in the catalogue recorded the source of the piece of wood, and often something of its history; the name and province of the residence of the donor; and the wood’s use within the One-Mat Room. In this way, each item was thus simultaneously mapped in geographical space, in historical time, in Matsuura’s own social network, and finally within the architectural space of the tiny study.

The One-Mat Room is a conceptually sophisticated embodiment of the way people can imbue even the most seemingly mundane objects with meaning. Even while questioning the legendary sources of some of the wood scraps, he recognized the history and relationships they represented. Smith adds some specific Japanese context:

The catalogue begins with a prefatory section that opens with a four-character Chinese phrase written by Sōkei Bokujū, the chief priest of Diatokuji in Kyoto: “Wood scraps send out light” (Koppen hikari o hanatsu). This nicely captures the aura of the One-Mat Room, and evokes the special Japanese feeling for wood as a medium of religious power. Trees themselves, of course, are the home of kami spirits, but the gods can also “reside” in inanimate objects, investing them with a spiritual power that can either threaten or protect. Japanese amulets (o-mamori), in particular, are for the most part made of wood or paper (itself a wood product). This enables us to conceive of the One-Mat Room as a comprehensive collection of talismans that gather in the protective powers of the greatest shrines and temples in Japan.

Matsuura, who was born near the Ise shrine, and in Mokuhen Kanjin, he stated that after his death, the One-Mat Room should be dismantled and used to cremate his body. The ashes should be scattered on Mt Odai, which is situated upstream from three of Japan’s most sacred sites, recycling the spirits embodied in these scraps.

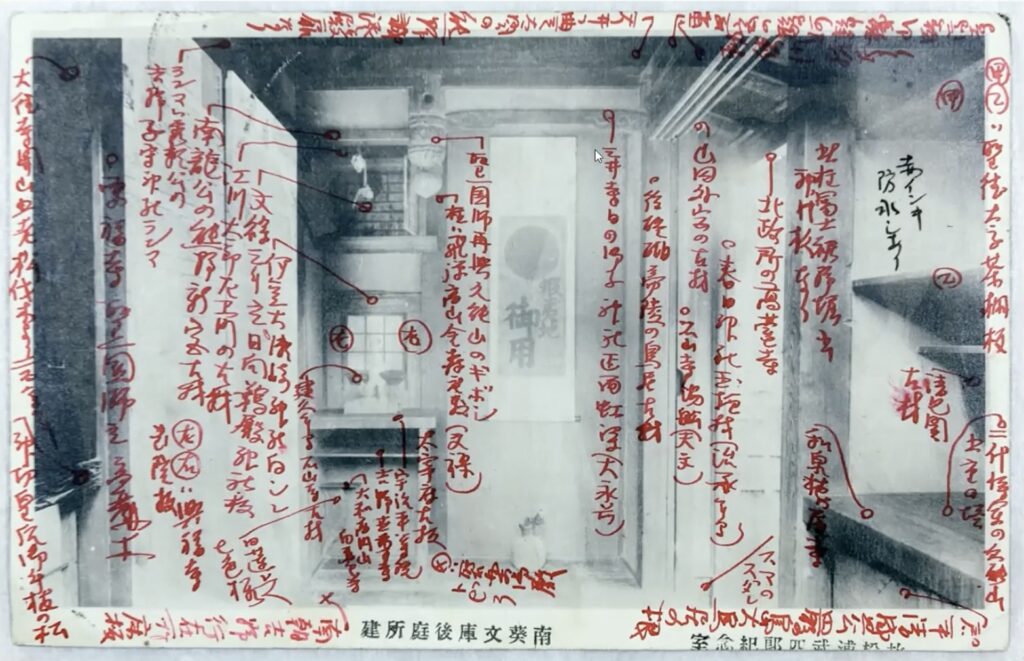

The One-Mat Room became momentarily famous in the early 20th century, when Tokugawa Yorimichi, a sort of pretender to the shogunate and a major force in Japanese historic preservation, acquired it from Matsuura’s grandson, and installed it in the garden of his private library in Azabu. I think this was the occasion for the publication of a commercial edition in 1908 (Meiji 41) of Mokuhen Kanjin. Shinshu University’s copy has been digitized. That is the only copy of Mokuhen Kanjin I can find online. [Well, here’s a picture of one from a blogger’s visit to a Matsuura exhibition at the Seikadō Bunkō Art Museum in 2018.]

Smith doesn’t say as much, but it seems The One-Mat Room became famous again after he and some ICU colleagues wrote about it. It is closed to most public viewing for conservation reasons, but a replica has been created, of this tiny structure made of uniquely irreplaceable pieces of ancient wood which is about the most hilarious thing I can think of. [a few minutes later update: there are two.] As far as I can tell, no facsimile of Mokuhen Kanjin has been published, nor has it an English translation.

Previously, related: Walden, Or The Afterlife of Wood

The Canes of the Martyrdom

A Walking Stick Frederick Douglass Gave To John Brown Would Be Quite A Find

Untitled (George Washington’s Coffin), 2016

*In 2012 Smith said 89 items were catalogued; in 2024 he referenced 91. Thirteen loose items—including the desk, hibachi, books, and paintings—were apparently lost in the move to Tokugawa’s library.