[STANDARD SPOILER ALERT] Despite what the global saturation ad campaign may imply, it’s better to approach My Architect as a spinoff–like a feature-length installment the Animatrix–not as a sequel. (That none of the actors from The Matrix films were in My Architect should’ve been my first clue.) Once I made this distinction, I was able to appreciate the movie much better; it turns out to be a moving, well-told story which happens to have an extremely misleading marketing strategy behind it. It’s the Shawshank Redemption of the Matrix Universe.

My Architect is set in the previous iteration of The Matrix, slotting into the Timeline somewhere between 1963 and 1974, although it includes trips backward and forward in time. The One here is a filmmaker named Nathaniel Kahn and is also called The Only Son. And the movie follows him on his quest to understand the Big Questions about his existence and his relationship to The Architect, who doesn’t look like Colonel Sanders in this film, but ressembles instead a somewhat homelier Danny Kaye, complete with big Architect glasses and a bowtie.

My Architect is set in the previous iteration of The Matrix, slotting into the Timeline somewhere between 1963 and 1974, although it includes trips backward and forward in time. The One here is a filmmaker named Nathaniel Kahn and is also called The Only Son. And the movie follows him on his quest to understand the Big Questions about his existence and his relationship to The Architect, who doesn’t look like Colonel Sanders in this film, but ressembles instead a somewhat homelier Danny Kaye, complete with big Architect glasses and a bowtie.

While some characters in the film react badly to the idea, there’s never any suspense about whether The Architect is The One’s father. For one thing (no pun intended), his name is Louis Kahn. Frankly, I couldn’t tell who is The Oracle. In a plotline taken straight from Star Wars, The One learns he has siblings, sisters–half-sisters, really–who also grew up thinking they were The One. It made for confusing family lives, and The Architect led a nomadic existence, hopping from house to office to building site to house, ultimately alone, even among his three “families.” Unlike Star Wars, though, The One doesn’t almost inadvertently hook up with his sister.

The Architect has uncompromising visions of a perfectly constructed world; the film tells many stories of his mighty battles with the forces of evil (called Clients, or in one case, Urban Renewal Planners). Ultimately, The Architect has to leave The Matrix itself, traveling to the then-new country of Bangladesh, where he harnesses the energy of the most un-plugged-in population on Earth to build his Capital. [This is a direct reference to the Animatrix episode about how the machines founded their country, 01, in a desolate corner of the Middle East.]

The Architect has uncompromising visions of a perfectly constructed world; the film tells many stories of his mighty battles with the forces of evil (called Clients, or in one case, Urban Renewal Planners). Ultimately, The Architect has to leave The Matrix itself, traveling to the then-new country of Bangladesh, where he harnesses the energy of the most un-plugged-in population on Earth to build his Capital. [This is a direct reference to the Animatrix episode about how the machines founded their country, 01, in a desolate corner of the Middle East.]

As we know from the movies, train stations figure prominently in the Matrix, and My Architect is no exception. The Architect dies of a heart attack in the men’s room at Penn Station. [This is not really a spoiler since the whole premise of the movie is The One’s search as an adult for The Architect/Father he barely knew as a child, his attempt to understand more about how The Architect spent his last moments, when, instead of being surrounded by at least one of his families, he collapsed alone in a bathroom.]

In a plotpoint that reminded me a bit too much of Kevin Smith‘s Dogma, where God goes temporarily AWOL because he (she, actually, since God is played there by Alannis Morrisette) went unrecognized in a hospital ICU, The Architect went unrecognized at the morgue for several days because he’s crossed the address off his passport. Nevertheless, both the enigma and emotional stakes faced by The One are touchingly conveyed, and this viewer found himself identifying freuqently with Nathaniel and his quest.

Did I say action scenes? Perhaps the most significant way in which My Architect varies from the Matrix formula is the utter and complete lack of action. Every time I thought, “here comes the big chase scene,” it was, “here comes another serene pan of a museum, library, and/or hall of parliament.” And while there were some tense moments, there weren’t any real fight scenes. Aunt Posie got pretty worked up, though, talking about her sister running off and having a baby like that. Just drives her up the wall.

Did I say action scenes? Perhaps the most significant way in which My Architect varies from the Matrix formula is the utter and complete lack of action. Every time I thought, “here comes the big chase scene,” it was, “here comes another serene pan of a museum, library, and/or hall of parliament.” And while there were some tense moments, there weren’t any real fight scenes. Aunt Posie got pretty worked up, though, talking about her sister running off and having a baby like that. Just drives her up the wall.

Kudos, finally, to the set designers. The series has always been known for its production design, but the dreary technoworld of the previous movies is replaced here by a seemingly endless parade of luminous, inspiring spaces. Very Logan’s Run. I wonder who did them.

What Nathaniel learns–and what he teaches us, of course, even in the title of his film– is that the quest isn’t for The Architect, but for My Architect. While the other Matrix films seduce us with the threat of an insidious, all-pervasive, artificially constructed reality, Nathaniel shows how much more enmeshed we become in the reality we fabricate inside ourselves.

Nathaniel’s mother recognized the stigma of having a married man’s child as an externally imposed social construct, and she rejected it. Yet her survival hinged inextricably on her belief that Her Architect was always just a passport edit away from leaving his wife. By definition, Nathaniel the filmmaker traffics in constructed, edited reality. He’s aware of the wilfully childlike innocence of his objective (he included scenes of himself rollerblading around the Salk institute or chasing his paper yarmulke in the wind at the Wailing Wall, after all), and yet he spent five difficult, emotionally wrenching years pursuing it with his camera.

Why get all worked up about The Matrix when My Matrix is more revealing and engrossing?

Hajji doin?

An update on Hajji, the Arabic term for “pilgrim” which has become the GWII term for “enemy”: it looks like it’s not just for GWII anymore. I found a Jan. 2002 usage in a short piece by Lisette Garcia, who writes,

Tampons, alarm clocks and Kodak film were easy enough for me to negotiate at the local Hajji shop. But giving a regulation haircut was simply too foreign a concept in the middle of the desert.

Garcia’s talking about the original Gulf War, I think, which gives the term a bit of breathing room, at least as far as its original coiners are concerned.

There are certainly some benign usages of Hajji around, and I can easily see how soldiers, hearing Arabs, Kuwaitis, or Iraqis address each other–or their elders–as “hajji,” could adopt it with clean intent. Try justifying the phrase “mowing down some hajjis,” though. I dare you.

For the record, this has nothing to do with Gus Van Sant.

Bloghdad.com/Hajji_Town

From Jay Price’s article in the Raleigh NandO: US Coalition US troops in Iraq have come up with this war’s equivalent of “kraut,” “slope,” or “gook.” They call everyone–everyone else, that is– “hajji.” It’s pronounced the way one soldier scrawled it on his footlocker, “Hodgie Killer.”

The ever-present, locally run on-base souvenir shops are called hajji shops; when there are several businesses together, they call it Hajji Town. Iraqis out the window of a Humvee, hajji. Kuwaitis and foreign contractors, hajji.

“This is more of a commonsense thing,” said [a CentCom spokesman in Baghdad]. “It’s like using any other derogatory word for a racial or ethnic group. Some may use it in a joking way, but it’s derogatory, and I’m sure people have tried to stop it.”

Pretty spin-free, for now. Killing Goliath, who pointed me to the story, got an imaginary spokesman’s spin that we can only wish was true: it’s like the brotherly love of Jonny Quest and his best friend. “but not in a pederasty sort of way,” “said” the soldier.

Pretty spin-free, for now. Killing Goliath, who pointed me to the story, got an imaginary spokesman’s spin that we can only wish was true: it’s like the brotherly love of Jonny Quest and his best friend. “but not in a pederasty sort of way,” “said” the soldier.

The real problem is that, to Muslims, hajji is not derogatory at all; it’s Arabic for “pilgrim.” It’s a title of respect and faithfulness, signifying someone who’s completed the hajj.

Like gook and kraut, hajji is used to distance oneself and dehumanize the enemy. But unlike past slurs, including GWI favorites like “towel-head” and “sand n***er,” hajji also religionizes them. So while Lt Gen. William Boykin preaches with impunity at home about this war against Satan, our unwittingly valiant Christian soldiers are faithfully “mowing down some hajjis” on the front. And intensifying Muslim distrust and hatred of the US.

More later. I’m off to church to pray for forgiveness.

[post-church update: Price’s article ran on Oct. 2, and I can’t find a single other media source who reports on hajji. Please prove me wrong. An earlier web citation is from August 17, when a Lt Rob Douglas uses it in his letters home, which get published in his local paper.]

Further reading: War Slang: American Fighting Words and Phrases from the Civil War to the Gulf War by Paul Dickson and Paul McCarthy.]

Sforzian Backstabbing

Since before Elizabeth Bumiller came up with the term for the Times, I was a fan of Sforzian Backgrounds, the news-manipulating slogans created by Scott Sforza, a key member of the White House’s advance scenery and production team, for just about every public appearance of George W. Bush. [After giving up hope for a commentary track from Sforza himself, I wrote my own interpretive post for Bush’s trip to Africa last July.]

And yet this week in a rare press conference, when he was asked about one of his Sforzian Backgrounds, Bush said, ” The ‘Mission Accomplished’ sign, of course, was put up by the members of the USS Abraham Lincoln, saying that their mission was accomplished. I know it was attributed some how to some ingenious advance man from my staff — they weren’t that ingenious, by the way.”

Talking Points Memo’s Josh Marshall is rightly shocked, shocked, that Bush is trying to pin the background on the military. I hope the unsigned report in the Times is a placeholder for an impending Bumiller story. In the mean time, I’ll call George W. on his transparent lie: his advance men are ingenious. [And they were behind the banner.]

In her first report on White House stagecraft, Bumiller reported that these advance men spent days “embedded” on the Abraham Lincoln staging the speech. “Sforza and his aides choreographed every aspect of the event.”

Sforza positioned the audience/crew in the background according to their uniform color:bright turtlenecks on the fighter wing (a favorite Sforzian spot, by the way), Army standard [thanks, Dan!]Navy service khakis in the front row. And to help them blend in with the troops, he put Bush’s Secret Service detail in Top Gun-style bomber jackets rather than their typical G-Man suits. Meanwhile, Bob deServi, the White House cinematographer, went the extra mile, turning the aircraft carrier around in order 1) to show a background of open sea and not the nearby San Diego skyline, and 2) to get the “magic hour” light just so on his boss’s face. The banner is instantly recognizable as Sforza’s–and the White House’s–ingenious vision.

The real question here is not who put up that banner, but why is Bush dishonestly and unfairly harshing on his loyal soldiers for it, both in the military and in the White House?

Related: Sforza’s version of Out of Africa

Whitehouse Stagecraft: Is this going to be on the DVD?

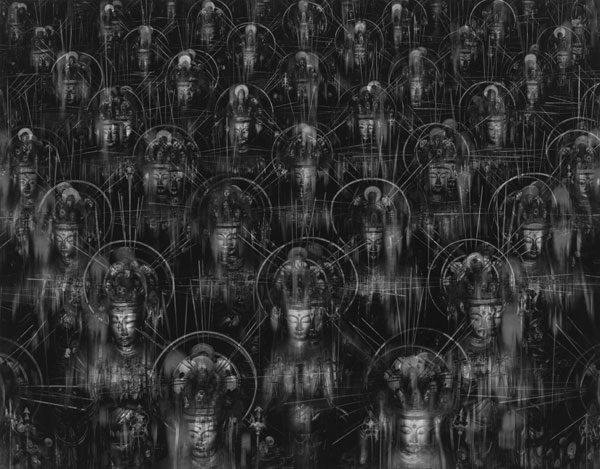

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Accelerated Buddha

Hall of Thirty-Three Bays, 1995, Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto: I came for the Seascapes, I stayed for the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays. I love Sea of Buddhas, 1995, his series of nearly identical photos of the Sanjusangendo, shrine in Kyoto. They’re generally under-appreciated, partly because they work best when seen all together.

Fortunately, Chicago has started making up for the Cow Parade embarrassment by putting the whole series of Sea of Buddha on view at the Smart Gallery at the University of Chicago until Jan. 4th.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Still image from Accelerated Buddha, added 2013

Also on view, the artist’s rarely seen video, Accelerated Buddha, which rocks like only an increasingly shimmering animation of nearly identical still photos with a sharp electronic soundtrack by Ken Ikeda can.

Related: an interview with Hiroshi Sugimoto [update, which I retrieved from the Internet Archive, since the original site is gone.]

Interview with Hiroshi Sugimoto, March 1997

by William Jeffett

Edited from Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK Catalogue Hiroshi Sugimoto, from an exhibition held 1997

WJ. How and when did you first take up working with photography?

HS. When I was six or seven years old, the science teacher at my elementary school taught us to make photographs with light sensitive blue paper. By placing an object on this paper under direct light we could transfer its shape to the paper’s surface. This activity made a strong impression, not only on the paper, but on my mind. As I think about it now, it was as if I had started at the very moment of the invention of photography as if I was reliving the experiences of photographers like Niepce, Daguerre and Fox Talbot.

WJ. You have lived in the United States for most of your career. How has this shaped the development of your approach to photography?

HS. Wherever I lived, art was the only activity that interested me. But both the move to a new country and the fact that photography is a relatively young medium seemed to welcome new attitudes. However, while living in a new country, I started to deal in ancient Japanese art and consequently was involved with continuity and tradition. I think my work is the product of both of these influences.

WJ. What does it mean for you to have a show in the Sainsbury Centre with its rich collections of world art?

HS. The Sainsbury Centre has a collection of several works of ancient Japanese art that were acquired from me while I was still a dealer, and I feel that this exhibition of my own work brings these two parts of my life and activities together. I think it is very good to see one’s work together with ancient art. Looking back gives a sense of perspective you cannot get when looking at works of your contemporaries.

WJ. Often there is a sense of stillness in your work, as if time were somehow frozen. Indeed, time is one of the features more evident in your work, and in the past you have even used very long exposures in a time lapse. Could you tell me about your thoughts on time in your work in general?

HS. Time is one of the most abstract concepts human beings have created. No other animals have a sense of time, only humans have a sense of time. But time is not absolute; the time measured by watches is one kind of time, but it is not the only kind. The awareness of time can be found in ancient human consciousness, arising from the memory of death. Early humans buried their loved ones and left marks at the grave site, trying to remember images of the dead. Now, photography also remembers the past. I am tracing this beginning of time, when humans began to name things and remember. In my Seascape series, you may see this concept.

WJ. Your work has taken both natural and highly artificial subjects as a point of departure (Seascapes and Dioramas). Where would you situate yourself in relation to artifice, on the one hand, and nature on the other?

HS. The natural history dioramas attracted me both because of their artificiality and because they seemed so real. These displays attempt to show what nature is like, but in fact they are almost totally man-made. On the other hand, when I look at nature I see the artificiality behind it. Even though the seascape is the least changed part of nature, population and the resulting pollution have made nature into something artificial.

WJ. Do you manipulate the image? In what way does your work interrogate the process of looking?

HS. Before we start talking about manipulation, we have to confirm the way we see. Is there any solid, original image of the world to manipulate from? Each individual has manipulated vision. Fish see things the way fish see, insects see things the way insects see. The way man sees things has already been manipulated. We see things the way we want to see. Of course I manipulate. Artists create excitement by manipulating a boring world. All art is manipulation, to take still photography with black and white images is further manipulation, but before all this the very first manipulation is seeing.

WJ. You work in series and in this respect your work parallels the approach of movements like Minimalism or even Pop Art. Could you tell me why you have adopted a serial approach and how you see your photography in relation to other forms of contemporary art?

HS. I see the serial approach in my work as part of a tradition, both oriental and occidental – Hokusai’s views as well as Cézanne’s landscapes or Monet’s Haystacks, Cathedrals and Waterlilies.

WJ. Do you see time as an important component in the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays series?

HS. Time is an important component of all of my work. In my videotape Accelerated Buddha, time takes on an accelerated shape.

WJ. Your earlier series devoted to the Dioramas, Seascapes and Theatres depict subjects which are not recognizably Japanese, while the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays is based on one of the most important shrines in Japan. Could you tell me why you chose this series to work on over the last six years and how it relates to your other work?

HS. All of my works are related conceptually. The photographs of the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays extend the concept behind the Seascape series: repetition with subtle differences. Even though these images seem similar to those of the Wax Figures, I see them more as a ‘Sea of Buddhas’.

WJ. In what way does the series have a connection with Buddhist thought?

HS. I don’t think that this series has more of a connection with Buddhist thought than any of my others. It interested me, however, that I was photographing this temple, built as a result of the fear of a millennium 2000 years after the birth of Buddha, at a time when we ourselves are approaching a millennium 2000 years after the death of Christ.

WJ. You said you made each of the photographs from this series at the same hour of the morning. Could you say why and explain a little about your working method?

HS. The photographs were all taken between 6.00 and 7.30am so that the natural light would be soft and diffused, also so that each image would be photographed in the same light. Working at this hour also allowed me to be alone in the Temple since the monks are not around until 7.30am. Each subject calls for different working hours. Only the Seascapes allow me to work 24 hours non-stop.

WJ. The Hall of Thirty-Three Bays depicts a sacred subject. Do you see your work as in any way engaged with the sacred?

HS. The relationship between the Buddha series and religious thought is somehow parallel to the one between the Seascapes and nature. Pollution has made nature artificial and the commercialization of traditional religions has de-spiritualized them.

2003-10-27, Talk of The Town

TALK OF THE TOWN

COMMENT/ RUSH IN REHAB/ Hendrik Hertzberg on pill-popper Rush Limbaugh’s hypocrisy.

S.I. DISPATCH/ THE WRECK/ Ben McGrath on the reaction to the Staten Island Ferry disaster.

DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY/ NOT LOST IN TRANSLATION/ Boris Fishman witnesses a major kissing of Mikhail Gorbachev at The Pierre.

DEPT. OF SIGNAGE/THE MAN AND THE HAND/ Nick Paumgarten talks about the walking man disappearing from the “don’t walk” signs.

DEPT. OF REMEMBERING/ TWO FROM BERLIN/ Jane Kramer talks September 11th memorials with Berlin conceptual artists Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock.

“We can easily believe that Bill Viola is worth ten Scorseses.”

Them’s fightin’ words. In his Cinema Militans Lecture, Greenaway thought he’d rile up his audience at the Netherlands Film Festival with his opening, “Cinema died on the 31st September 1983.” (Killed by Mr. Remote Control, in the den, if you must know.) But it’s his claim that Viola’d trump Scorsese that’s the real “they bought yellowcake in Niger” of this speech. He’s just got Britishvision, distracted like a fish by a shiny object passing in front of him [Viola‘s up at the National Gallery right now.] And the conveniently timely evidence he cites seems, well, let’s just say we know from conveniently timed evidence over here.

Sleeping with the enemy: Greenaway

texts up a set of bed linens. for sale at bonswit.com

Greenaway argues for a filmic revolution: throw off the “four tyrannies” of the text, the actor, the frame and the camera, banishing at last the “illustrated text” we’ve been suffering through for 108 years, and replacing it with true cinema.

The Guardian‘s Alex Cox sees video games and dvd’s rising up to answer Greenaway’s call, and he makes the fight local, pitting Greenaway against the British Film Establishment, as embodied by director Alan Parker. So the choice is either Prospero’s Books or The Life of David Gale?? This fight’s neither pretty nor fair.

Also in the Guardian: Sean Dodson’s report on a Nokia-sponsored campaign for the new future of cinema, a “festival” of 15-second movies to watch on your mobile phone. It’s part of London’s excellent-looking Raindance Film Festival, and it embodies perfectly the

More than rallying the troops, Greenaway and Nokia are actually tottering to catch up with the next generation. Paul Thomas Anderson’s inclusion of Jeremy Blake’s animated abstractions in Punch Drunk Love. The Matrix Reloaded‘s all-CG bullet time “camera.” The Matrix launching the DVD player, for that matter. Gus van Sant’s Gerry as film-as-video-game and the multiple POV reprises of scenes in Elephant. Multi-screen master Isaac Julien, Matthew Barney, spawn of Mario Brothers. And the unscripted cinematic narrative mutations of corporate-sponsored mediums like PowerPoint and AIM buddy icons.

More than rallying the troops, Greenaway and Nokia are actually tottering to catch up with the next generation. Paul Thomas Anderson’s inclusion of Jeremy Blake’s animated abstractions in Punch Drunk Love. The Matrix Reloaded‘s all-CG bullet time “camera.” The Matrix launching the DVD player, for that matter. Gus van Sant’s Gerry as film-as-video-game and the multiple POV reprises of scenes in Elephant. Multi-screen master Isaac Julien, Matthew Barney, spawn of Mario Brothers. And the unscripted cinematic narrative mutations of corporate-sponsored mediums like PowerPoint and AIM buddy icons.Greenaway’s righter than he knows, but the evolution’s already underway, with or without him. It always has been

Whereas, Ten Hours of Polish Film is NOT an Ordeal…

I came to Kieslowski for the fateful mystery of La Double Vie de Veronique, but I stayed for the unassuming, naturalistic power of the Dekalog.

This seminal ten-part series of films is playing this weekend at Symphony Space in NYC. POV has an excellent write-up, with good links to get you in the mood.

The Decalogue was one of the greatest unwatchable works of film, ever. For years in North America, the series, which Kieslowski and writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz originally made for Polish TV, was kept off of video and DVD by weird rights disputes. But it’d turn up at film festivals and cinematheques, and you’d suddenly have to figure out how to shoehorn ten hours of moviegoing into two or three days. It was an experience prewired to disappoint, or, more precisely, leave you wanting.

By 2000, I’d only managed to see half of the installments, when an odd one-year distribution agreement brought a bare-bones 2-DVD set to the market. I snapped it up, and since then I’ve been steeping regularly in some of the most engrossing storytelling around.

This year, The Decalogue reappeared in a far superior 3-disc format, complete with several Kieslowski interviews and other real supplementary material. So get up to Symphony Space for at least a couple of episodes, then watch and rewatch them at home. Of course, GreenCine rents them one disc at a time; it may be better, emotionally, to pace yourself.

[related: the effects of watching Dekalog on an impressionable new filmmaker]

On Transit and Memory

Santiago Calatrava talks about his vision for the transit hub he’s designing for the World Trade Center site. I’m a fan, although there doesn’t seem to be a lot of design meat here.

And the New Yorker‘s Jane Kramer gets Berlin artists/memorial designers Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock to talk about a memorial for the World Trade Center. Their comments seem well suited to the discourse of a year or so ago, when entertaining the world of possibilities didn’t feel so escapist as it does now.

In fact, last year, I was very impressed by their proposed Holocaust memorial.

More Olafur Eliasson Pix

The Weather Project, 2003, Olafur Eliasson, at the Tate Modern

The top one’s shot in the mirrored ceiling.

I’m working on it, but right now, I got nothing that’ll top this.

tate update: sun worshippers

the british public treats it as the real sun, laying out on their backs as if at the beach.

[10/21 update: like I said…]

Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project at Tate Modern

Just got back from the preview and party for The Weather Project, Olafur Eliasson’s absolutely breathtaking installation at the Tate Modern in London. The Turbine Hall is something like 500 feet long, the full length and height of the building.

I can tell you that Olafur created a giant sun out of yellow sodium streetlamps, but that doesn’t begin to describe the experience of seeing it and being in the space. It is this awareness of one’s own perception which is at the heart of his work. Not only does he use and transform this unwieldy cavern, he intensifies the viewer’s sight and sense of being in the space.

And as always, Olafur lays bare the mechanisms that create the unavoidably sublime experience, which in this case include, literally, smoke and mirrors. You can see exactly how you’re being

[update: the Guardian‘s Fiachra Gibbons likes it, too.]

Seeing Lost In Translation on the Upper East Side

Context isn’t everything, but it counts. We just got back from seeing Lost In Translation with a multi-generational crowd, in the movie theater around the corner from Holly Golightly’s brownstone. As they say, it’s the little differences:

Chia-Church

The artists Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey and their team of 15 people plastered the walls of a church in South London with clay and grass seed. Read their diary at the Guardian and watch it grow to Graeme Miller’s soundtrack.

Related: visiting information from the London International Festival of Theatre

More info on Ackroyd & Harvey and Miller on Artsadmin

I Report, You Decide: Speaking with a former WTC juror

Friday, I met an architecture professional who was on the LMDC jury last summer to select the architects for the World Trade Center site design study. We spoke about the Memorial Competition, details of which were familiar to this person.

The juror was deliberately cagey, but said the Memorial jury was down to ten proposals: “And when it gets down to ten, the lines start to sharpen.” Asked about the timeline, this person said, “very soon,” but when I bounced the rumored names of finalists, the response I got was, “you know more than I do, then.” (Which is so clearly not the case, it’s almost embarassing.)