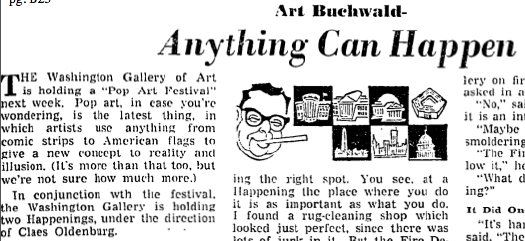

I've already mentioned the May 3, 1963 Time Magazine article about the Washington Gallery of Modern Art's Pop Art Festival; it's really not much, but it contains the most extensive contemporary account of Claes Oldenburg's 1963 Happening, Stars. Here's how they reported the grand finale:

Red Gee String.All these activities map very closely to Oldenburg's script, which was transcribed and published with his Raw Notes in 1971. But these incomplete accounts generate as many questions as they answer about how Stars took shape, what actually happened, and what happened afterward as a result.

As the evening wore on, slides of naked women were projected, suggesting that pornography has its place among the neo-Palladian splendors of the alabaster city. Waiters spilled bits of plastic from trays onto the audience. A woman came on wearing a shredded American flag on her head; her spine was as stiff as a flagpole. It had to be, since it was part of the monument to the victory at Iwo Jima, and three soldiers held her at the appropriate tilt. A 14-year-old boy in a Lincolnesque beard entered the room, was shown to his seat, and sat there waiting to be shot. Zow.For the closing number, Miss Washington, stacked like the melon gallery, appeared in a mass of red taffeta. She pulled her rip cord, and there she stood--after all, it is the nation's capital--not quite nude. An aw-gee string. A suggestion of red taffeta there-there and there.

She turned and bolted like a moose, followed by official Washington, gurgling hip-hip for happenings.

I finally decided to go to the source. Last week I spoke with Alice Denney, who organized the Pop Art Festival and curated the Popular Image show it accompanied. She was generous and awesome, and not a little bemused at my questions--or that I was asking them at all.

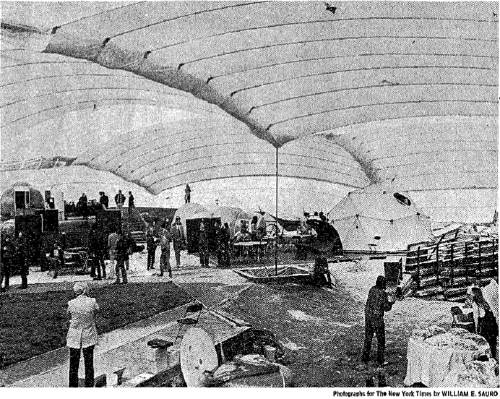

How many Happenings were there? When and why did the site move from the cleaners to the Gallery, and how did that affect it?

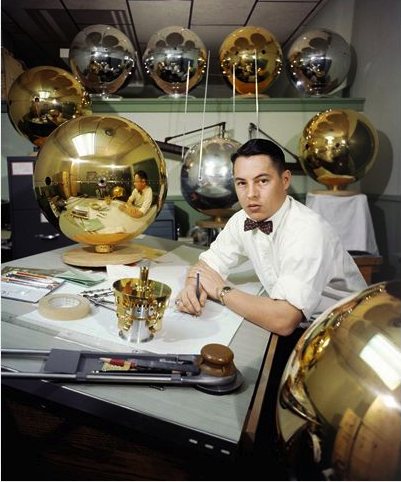

AD: We thought we could do it in the rug cleaning place on P Street, but a few days before, a couple of the trustees came in and said, "You couldn't do it there, there's no egress." So we moved it.Ah, so Olga Kluver was the one in the red taffeta dress. In 1963, though she was living with Billy Kluver, she still went by Olga Adorno. Kluver, of course, had helped organize another major event for the Festival, a multi-stage dance performance by the Judson folks at a roller skating rink in Adams Morgan. Meanwhile, in 1964, Andy Warhol threw a party to celebrate Adorno and Kluver's marriage....

[The content] didn't change, even though the space was much tighter. We used the stairway so that Olga Kluver could come down.

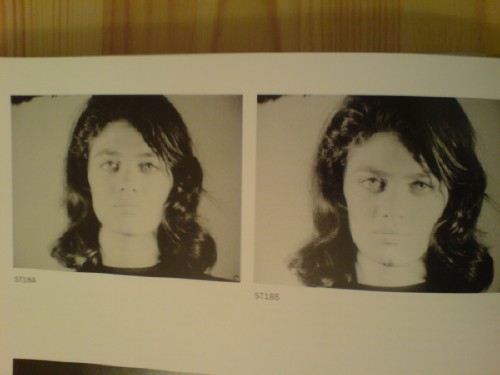

Adorno appeared in at two of Warhol's Screen Tests, ST184 and ST185, both in 1964. She also performed in Happenings by Allan Kaprow, Red Grooms, and Robert Whitman. Apparently, Adorno's still going strong, creating enigmatic performance works from her base in Nice, France. But back to Mrs Denney, who was the gallery staffer mentioned in Time as making blue ice cream and serving it on picnic plates, and whose son was the stand-in for Lincoln:

...It was all about Washington: the monuments, the dinner parties...And it turned out to be quite popular. The reservations filled right up for all three Happenings [one on Wed., Apr 24, and two on the 25th]. Mrs Denney mentioned that in addition to performing in Stars, Claes's first wife, Patty [Pat Muschinski], worked on many of Oldenburg's soft sculptures and costumes, and wrote a memoir of the Happening for Art in America. And so the chain continues.Everybody wanted to go, and all the fancy folks wanted to be in it.

But it was pretty much my gang of crazies, [Claes] didn't want society ladies.