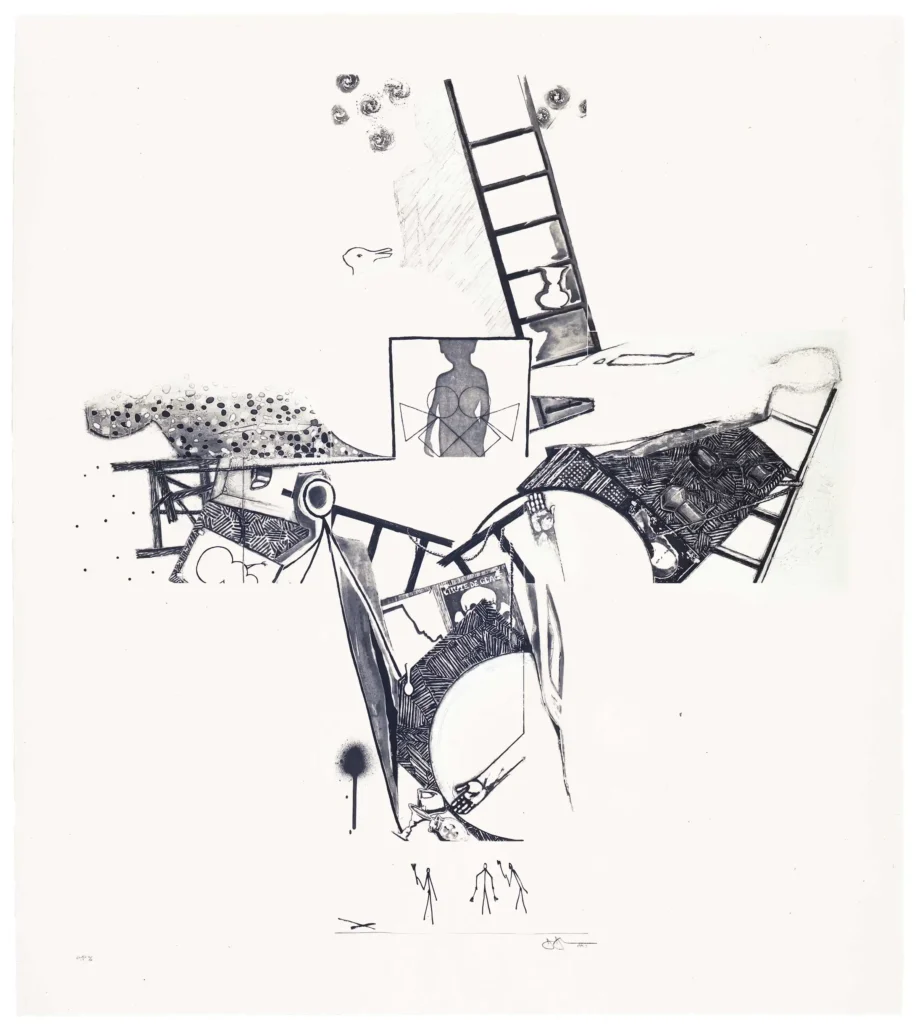

![a mostly black on white jasper johns print is a dense composition of recognizable elements from his work in 1992 and before: trompe l'oeil paper prints of barnett newman etchings and a large photo of a spiral galaxy sit on top of an outline traced from the isenheim altarpiece, recognizable as something figural, or copied, but hard to discern. in the lower left corner is his optical illusion vase made from two profiles of, presumably, himself. on top of the galaxy are printed ladder fragments, a silhouette of a small child, the latter in blue, and inside [sic] the vase, three stick figures with brushes are printed in red against the grey gradient interior, hard to pick out. these elements all match up to etching plates from the seasons, a print johns made two years earlier, in 1989-90, so this is a crossover combo of several sets of elemtns, or series of images. a gift of the artist to the walker art center](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/johns-untitled-little-guys-1992-wac-1024x853.jpeg)

You’d think I’d have taken the hint sooner. Like after seeing the big jump around 2001 of appearances of the three little, brush-wielding stick figures in Jasper Johns drawings—because they were in the prints he was reworking. Or after finding little guys gazing at the stars in the 1997 etching he made for Leo Castelli’s 90th birthday portfolio.

But no, it took finding little guys in Johns’s 2008 Artists for Obama print that made me realize there was much I didn’t know about Johns using the little guys motif in his prints. And it turns out they’re all over the place. Johns is a printmaker who paints, and his imagemaking crosses mediums with the ease Canadians used to have crossing the US border. So I was missing a big part of the little guys story.

TBF, I’d done some work, looking at the archives of Johns’s primary print foundries, Gemini GEL and ULAE. But the Gemini CR is currently frozen at 2006, and Johns set up his own printworks in Connecticut. So there are gaps. Fortunately, he’s been giving the Walker Art Center an example of every print he makes.

I count fifteen appearances in prints by the stick figure trio up until the pandemic—the latest batch of prints was donated in 2020—beginning in 1989 with The Seasons (ULAE 0249, 1990), the large, cruciform intaglio print that combined elements from the larger, four-image series. They come in groups, or are at least related. The untitled 1992 print at the top, with the trompe l’oeil Barnett Newmans, appears to have some of the plate elements from The Seasons in it as well, mostly on top of the galaxy. But there are also faint stick figures inside the optical illusion vase. This 1998 print is like a quarter the size, but it contains a scaled down rendering of The Seasons cross, with redrawn stick figures. [Also, there’s the UNESCO Picasso stick figure, which just feels like its own thing.] Stick figures in the vase reappears, too, but like twenty years later, in a 2011 shrinky dink print. [I loved that show.]

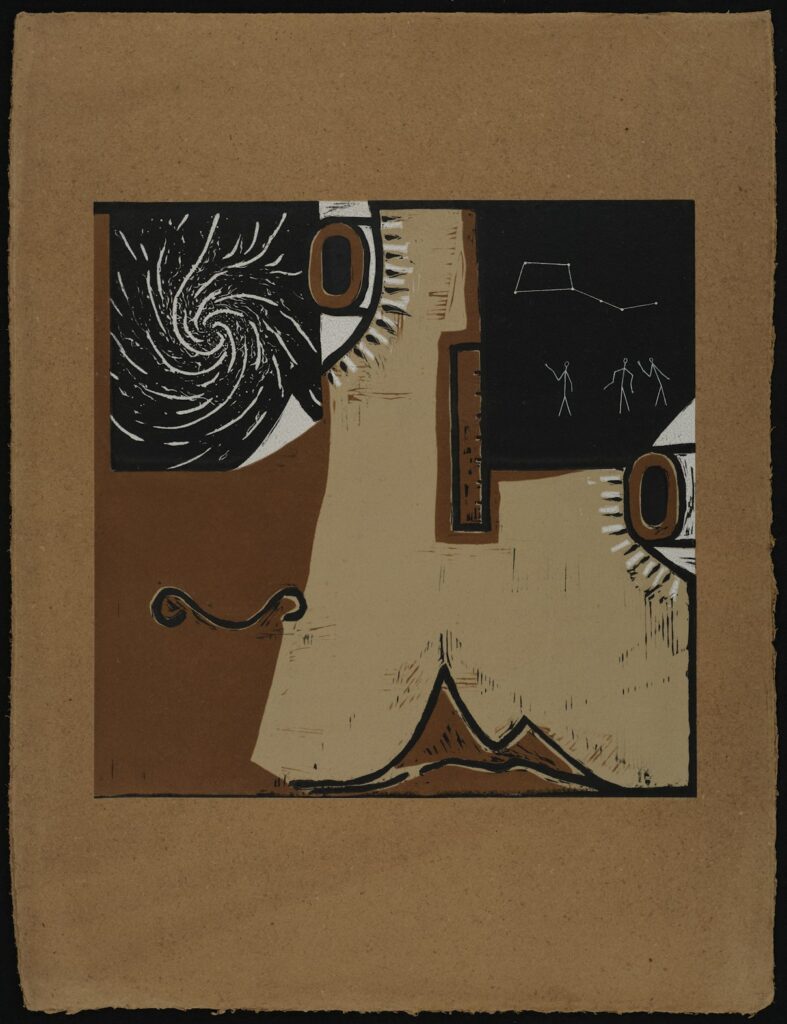

But that skates past the 2001 catenary prints, the rejects of which Johns reworked by hand. Then there’s a cluster of linoleum prints in 2016 in which the little guys look at the Big Dipper, amidst the disassembled Bruno Bettelheim face.

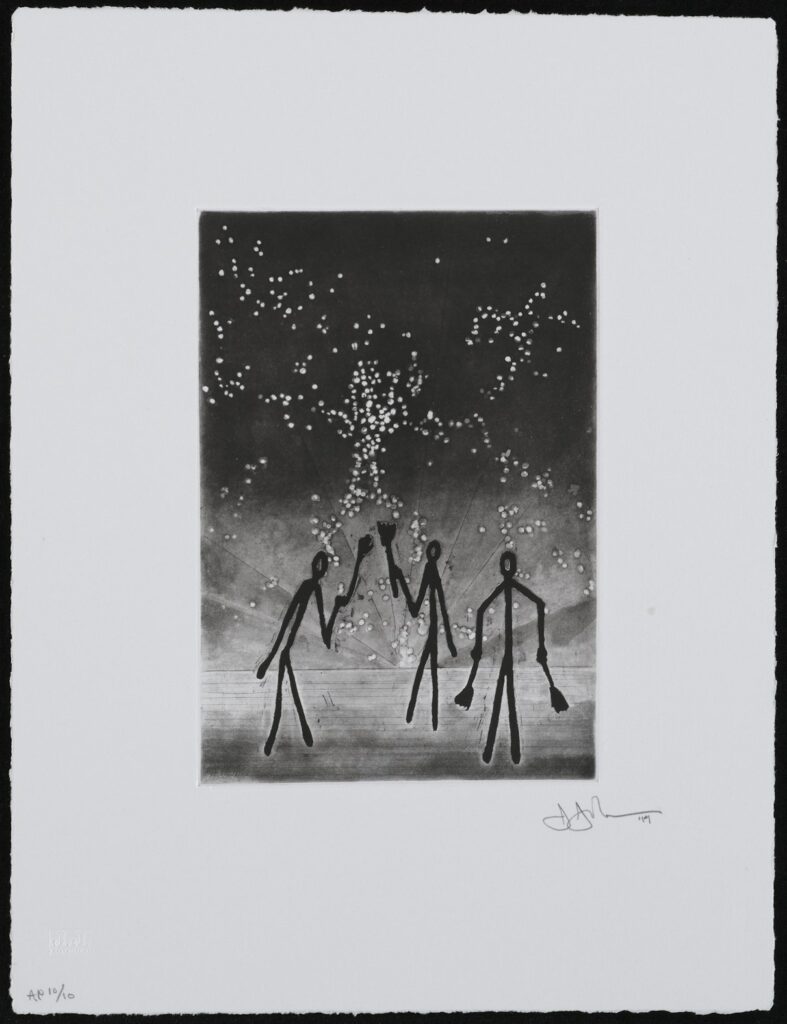

And then it comes full circle, to the little guys that started it all, and by it, I mean my fixation on these little guys. From 2018, Johns really put the stick figures to work, and they were everywhere, doing all kinds of stuff. It was these prints and related drawings that made such an impression in Johns’s last two shows at Matthew Marks, in 2024 and 2021—the one with the knee thing, remember? A little 2019 print in that 2021 show is one of my favorite little guys images: they’re out under the threadlike structure of the universe, admiring the diagram astrophysicist Margaret Geller sent to Johns several years earlier.

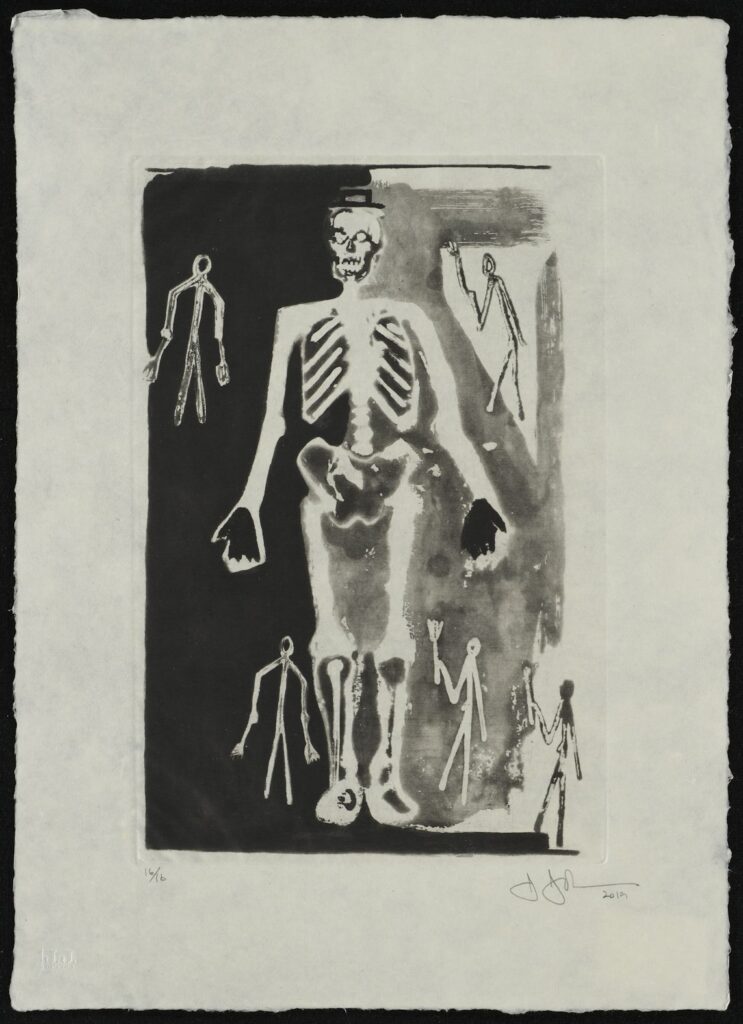

There are a couple of prints that echo the drawings of stick figures surrounding Johns’s skulls and skeletons. This one makes them feel Lilliputian, or maybe rather than captors they’re Promethean creators. Or at least X-ray techs. Maybe Johns’s dancing skeletons and bouncing skulls are not symbols of inevitable death, but of care and insight into our human essence. Or death, death is a possibility, too.