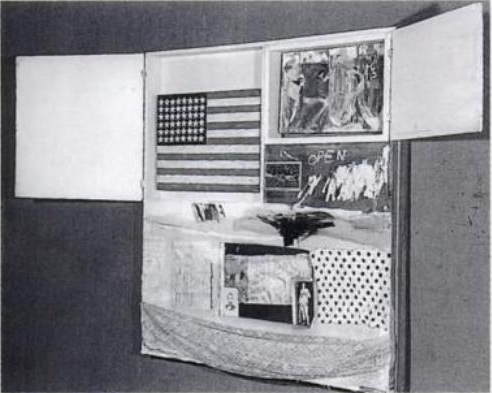

After a brief break, during which I briefly pwned Miami Art Basel, the search for the Jasper Johns flag painting which was included in Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine-painting Short Circuit [above], continues.

Actually, because I had to carry on the oddball contents of the gift bags I did for my #rank presentation, I went to the airport freakishly early and ended up with extra lounge time, which let me read through all the details and footnotes in my pristine, OG copy [apparently from the library of Artforum!] of Dr. Roberta Bernstein’s definitive 1985 dissertation-cum-catalogue raisonné, Jasper Johns’ Paintings and Sculptures 1954-1974, “The Changing Focus of the Eye.”

Only guess what, it wasn’t there. Not a mention, not a photo, not a footnote, not a trace.

[UPDATE: Since posting this in December, I have communicated with Dr. Bernstein about the Short Circuit flag and its absence from her thesis, as well as its status in her forthcoming Johns catalogue raisonne. Scroll down for her gracious and informative reply.]

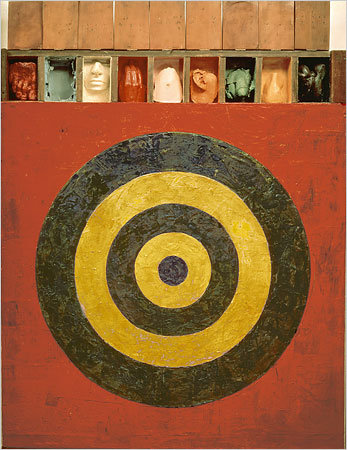

Johns’ artistic career starts, as anyone who passes through MoMA knows, with the destruction of almost all of the work he made before 1954. And while Bernstein mentions a handful of existing works that precede it, Johns’ revolutionary story really starts with Flag (1954-55, which has since been redated 1955), Target with Plaster Casts (1955) [above], and the first painting he exhibited in New York, at a 1957 group show at the Jewish Museum, which freaked Leo Castelli out and started the whole thing rolling, Green Target.

Or maybe it’s the first painting that wasn’t incorporated into Rauschenberg’s work, or subsumed, really, since no exhibition credit was given to Johns [or for that matter, to the other two artists whose works went into Short Circuit.]

As I’ve been looking more closely at the history of Short Circuit, and at Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s relationship, and at the resonances and dialogues between their work during that time, I can’t help wondering if Short Circuit and the flag in it aren’t a part of Johns’ early career story he doesn’t want to emphasize. Actually, it’s absolutely the case that Johns doesn’t want to emphasize it. The question, then, is the extent to which Short Circuit and its flag–the first one exhibited, if not the first one made–have been neglected, forgotten, or ignored, and the extent to which they’ve been buried or concealed.

Granted, Short Circuit itself remained in Rauschenberg’s collection, and the Sturtevant replica Johns Flag has been there, visible, but different, for at least the last 35 or so years. But I guess my particular question is less about Short Circuit–and Rauschenberg–than about the flag–and Johns.

Bernstein’s book began as her 1975 doctoral dissertation. Her objective, she wrote, “is to present a detailed, comprehensive examination of the first twenty years of Jasper Johns’ paintings and sculptures.” [Gone emerita from SUNY Albany, she’s working right now on the official Johns painting and sculpture catalogue raisonné, to be published under the auspices of the Wildenstein Institute.]

As an art graduate student at Columbia, Bernstein worked for Johns in 1968-69, and she drew extensively on her daily conversations and journals kept since she first met him in 1967. She also used the artist’s own records and notes, including a file of his works he maintained on index cards:

Through my personal contact with Johns, I have acquired much information and gained many insights which have provided what i consider to be a sound basis for interpreting his art. This study is an attempt to share that knowledge and experience.

On the period of Short Circuit‘s and its flag’s creation and context, Bernstein writes with the elliptical understanding and reticence that reflects the time–and her subject’s temperament:

Rauschenberg and Johns were close friends for six years, and many aspects of their work reveal a common sensibility and similar artistic concerns. Their friendship ended in 1961-62, and the tone of emotional crisis reflected in Johns’ works from that period is probably connected with that break-up.

Bernstein’s account, then, is not official, but it is certainly presented as as close to the artist’s version of the ‘truth’ as it can be.

In such an account, the absence of a single mention of the Short Circuit flag seems meaningful, and can be accounted for by one or more of the following:

- Johns did not include the Short Circuit flag in his file of works.

- Johns did not discuss or mention the painting to Bernstein between 1967 and 1975, when her dissertation was submitted. Or by 1985, when it was expanded and published.

- Johns and Bernstein discussed the Short Circuit flag, and a decision was made not mention it.

Considering that the Short Circuit was exhibited and the flag was reportedly removed in 1967-8, during Bernstein’s acquaintance and engagement with Johns, and that it directly relates to the development of Johns’ first major thematic series, it strikes me as implausible that the subject of the little flag would not have come up.

So it is likely, then, that decisions were made to not include it. Whether because it was not considered a work, or not an autonomous work; whether it was contested or problematic, or negated somehow; or whether because it concerned “Johns’ relationship to his contemporaries,” a “thorough handling of which,” as Bernstein wrote in her preface, “does not fall within the scope of this study,” it was absent.

So far as I can tell, the thorough handling of Short Circuit and the Johns flag it originally enclosed has not been done.

UPDATE As mentioned above, I contacted Dr. Bernstein, and she informed me that she had no knowledge of the Short Circuit flag while she was writing her dissertation, and that Johns had never mentioned it during her tenure or her time working on the book. It will be included in the catalogue raisonne, however. She also mentioned that she had searched for the flag painting and had been unable to find it. Needless to say, I am very stoked and grateful for her highly informed response.