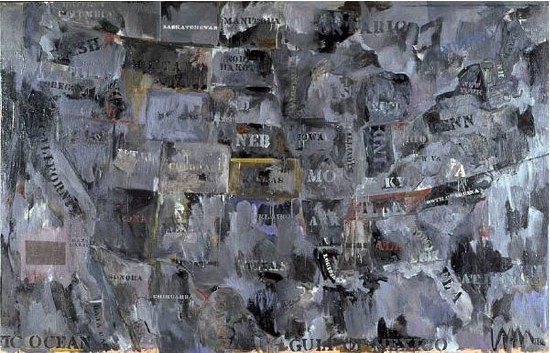

Map, 1962, Jasper Johns, via moca.org

For her contribution to the Jasper Johns Gray (2007) catalogue, Barbara Rose writes about the history and significance of Map, 1962, the artist’s first big, gray masterpiece. Johns made it to raise money for his new Foundation for Contemporary Arts, which was founded to stage some performances of Merce Cunningham. Marcia Weisman bought it out of Johns’ studio and ended up leaving it to MoCA.

Rose suggests that Johns’ Map paintings are akin to battlefield maps, and that the gray one, in fact, resonates with a particular Civil War battle, the Battle of Antietam. She cites Johns’ own South Carolina upbringing, the centennial commemoration of the Civil War that was in the news in 1960-2, and a series of paintings by Frank Stella which drew some of their titles from Civil War battlefields. [Rose was married to Stella at the time, of course, and also refers to one diptych from the series titled Jasper’s Dilemma.] Also, Rose writes, “The difficult realities of Johns’s personal life coincide with the idea that this map pictures a battlefield.”

After recounting some formalist skirmishes with General Clement Greenberg’s troops, Rose zooms in on the surface of the painting and on some of the collaged elements in Map that Johns intentionally left visible:

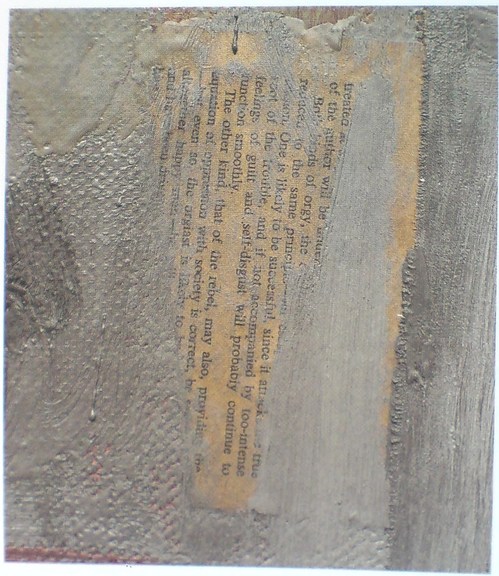

Topographically, the hills, ridges, and ravines of Johns’s gray Map suggest geological strata bursting. Paint washes over the surface like sea spume or waves eroding coastlines. Known borders are changed or blurred. This transgression of boundaries is a physical fact of art historical as well as personal significance. The surface is scarred and scraped in areas so that the printed matter sealed into it with adhesive encaustic is visible. The most tantalizing fragment is not newsprint but part of a page, probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio. One can make out the words “intense feelings of guilt and self-disgust,” as well as “rebel” and “orgiast.” These chosen and deliberately revealed phrases participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter.

Map detail, via Jasper Johns Gray

Lots of interesting stuff, but I am most fascinated by the overall strategy Rose adopts, of floating the connection to “the difficult realities of Johns’s personal life,” and then going both wide and deep about everything but.

In her strategy and language both Rose echoes a 2006 Artforum essay by Yve-Alain Bois on the difficulties of seeing Rauschenberg’s combines. Using Minutiae, 1957-9, for his example and Paul Schimmel’s MoCA show and catalogue for his hook, Bois notes how Rauschenberg denies, thwarts or taunts the idea of a proper viewpoint.

Minutiae, 1954, Robert Rauschenberg, image via centre pompidou

Because Minutiae was first created as a freestanding prop for a Merce Cunningham dance performance, and was thus only viewed at a distance, Bois questions the validity a close “reading” of the raw materials Rauschenberg used, calling them “hide-and-seek booby traps”:

More often than not, the collaged surface of the work suggests a complex geology; it tells us that there is something behind but denies our access to it. Frustrated at not being able to dig for the “woman underneath” (to borrow Balzac’s famous ending of The Unknown Masterpiece), many of Rauschenberg’s commentators can’t resist biting at the referential bait he has generously distributed across his surfaces in, I presume, as tongue in cheek a manner as did Duchamp. Setting these semantic traps might be considered cruel of him, but it could also be deemed charitable, keeping art historians busy for generations to come. As Leo Steinberg wrote in his recent revisitation of his groundbreaking 1972 essay (based on a 1968 lecture): “We shall have dissertations galore, including perusals of the fine print in the newspaper scraps that abound in Rauschenberg’s pictures.”

First off, why just presume? Can’t you figure it out, or ask? Second, that was no woman, that was his husband. Bois notes that for all the referential parsing in Schimmel’s show and catalogue, gay interpretations are not even on the map:

My favorite example of this sheepishness concerns “Plymouth Rock,” which is dissected ad nauseam by two of the catalogue’s authors. [It’s typically called Untitled (Man with White Shoes); Schimmel writes that the artist often called it Plymouth Rock because of the chicken. -ed.] We learn about many of its affixed elements, right down to a newspaper clipping about a beauty pageant won by Rauschenberg’s sister that is visible reversed in a mirror only after considerable gymnastics on the part of the viewer. But there’s nary a peep about the faded photo of a youthful Jasper Johns staring the viewer in the face at eye level. There, the sexuality-inclined iconologists have a point: Playing the hide-and-seek game might still have some social function today–at least with regard to a topic like homosexuality in the America of Brokeback Mountain.

And here is Rose, a year later:

So much has been conjectured about the relationship between Rauschenberg and Johns that it seems idle to add to this burgeoning literature. But there is still a lot to be said about the complex artistic dialogue between the two, an exchange that began in collaboration and ended in competition.

Untitled (Man With White Shoes), or Plymouth Rock, 1954-1958, actually, image via artnet, I think

Yes, but so what? asks Yve-Alain Bois:

[T]he question to ask is this: What does the identification of a face–even one that alludes, for those in the know, to the private life of two extremely secretive artists–fundamentally add to our understanding of the work? Given the dozens of conglomerated atoms in “Plymouth Rock,” including photos of various scales (among them several family snapshots), reproductions of works of art, a Cy Twombly scribble, a stuffed hen, a mirror, and a pair of shoes, what could the pinpointing of individual elements achieve, especially as they might branch into different stories in the minds of the iconographer-sleuths? Would we finally have found Waldo?

Well, if Rauschenberg slept, lived, traveled, exchanged ideas with, and made work with Waldo, too, maybe it’s worth knowing? Maybe such sleuthing can add to our understanding of how these artists actually worked together, or alongside each other, and how they actually made their works?

Or when? Detailed investigations of source material in both Plymouth Rock and Johns’ Flag show that the artists kept working on the pieces for years after their “official” 1954 creation date.

Or maybe these thwarted vantage points, these exercises in revealing and concealment, can help add to our understanding of how a gay artist couple managed to launch two of the most productive and influential art careers of the 20th century during one of the most homophobic periods in American history?

Schimmel worked with Rauschenberg on the combines show; Rose’s essay was followed immediately by an interview with Johns. Either one of these shows, you’d think, would be a good time to cut through the conjecture. But no. Instead of Brokeback Mountain, this sounds more like art history in the America of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

It’s been a hallmark of critical writing about Johns and Rauschenberg that their relationship during their most important period can only be inferred or alluded to or dismissed out of hand, just as the dramatic, fraught shift in Johns’ work that followed their 1961 breakup can only be conjectured upon.

And even as they acknowledge the artists’ early interactions, “Many writers,” as Schimmel [too] points out, “correctly observed that they were, and remain, opposites in temperament.” This difference serves to reaffirm what Rauschenberg told Calvin Tomkins way back in 1982, that “being so close to each other’s work kept any incident of similarity from occurring.” And yet critics end up using almost exactly the same language to [separately] describe the works and ideas of each artist.

To Bois, Rauschenberg’s great idea with the combines is a Cageian declaration of, “the entropic equalization of all things,” a proto-postmodern gauntlet thrown down to the Abstract Expressionists that “there is no fundamental difference between a collage element and a painted one.” But isn’t that exactly what Rose is saying about the “chosen and deliberately revealed phrases” in Johns’ collaged page of text?

Of course, Rauschenberg also made art from a Johns painting [and a Weil, and a Johnson.] If anything, the subsequent, silenced history of Short Circuit, and the post-breakup agreement Bob and Jasper put in place to not exhibit or reproduce it, simultaneously underscores the artists’ awareness of a collaborative aspect to their most iconic, important works–and to their ongoing determination to quash any discussion of it.

At least at the time. Johns most expansive, recent series of Catenary paintings, the climax of the Gray show, seems directly related to an early Rauschenberg combine with a parachute affixed to it, which Johns bought, post-breakup, in 1963, and kept for decades. And maps are a specific motif that Johns received–and acknowledged receiving–from Rauschenberg in 1960, a motif Rauschenberg himself had used in his own work. What others might there be?

At the risk of being dismissed as just another iconographer-sleuth, and because I can’t think of a word that seems farther removed from Johns’ work than “orgiast,” I tracked down the source of that “most tantalizing fragment” Rose referred to. It’s located in Eastern Idaho [above], on the Wyoming border, so maybe the Brokeback reference applies after all.

The page is from an awesomely titled book by Burgo Partridge: A History of Orgies. Burgo, whose first name was Lytton, as in Strachey, was the son of Bloomsbury Group members Ralph and Frances Partridge. He wrote A History of Orgies in 1958 at Oxford, and it was apparently successful enough in England to keep his friend Anthony Blond’s poetry publishing company afloat, and to get published in the US in 1960.

Though it took me approximately five minutes in Google Books to identify Partridge’s work as Johns’ source, the full text was not available. So to my wife’s bemused consternation, I have purchased a first US edition, and sure enough, the preface matches the fragment Johns used in Map exactly. So I will transcribe the short preface and see what, if any, relevance it may have to Johns’ work. Stay tuned.

Aaand here it is, from Jasper Johns’ A History of Orgies