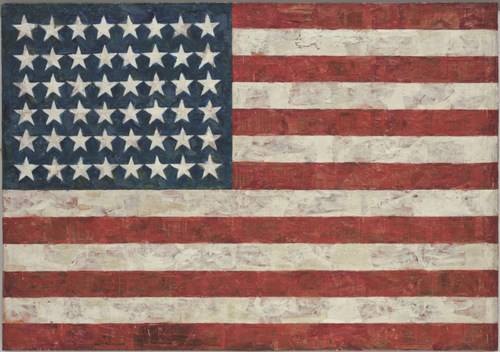

Flag, 1954-55, collection and image: MoMA

When, after a couple of weeks of poking around, I didn’t stumble, Banacek-style, onto the Jasper Johns Flag painting from Short Circuit, and then flip it for my 5%, reunite it with Rauschenberg’s combine, and get on the front page of the Arts & Leisure section again [ahem], I did kind of wonder what the end game of this search might be.

At some point might the result just be an acknowledgement that the flag is lost, fate unknown? And if so, does it just remain an entertaining art mystery, but a footnote to the “real,” relevant history of Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s work and all that flowed from it?

Fortunately, I don’t think that’s what happens here. No matter if it never resurfaces, the Short Circuit flag deserves a place in art history as the first Flag Johns showed, by almost three years. It is also almost certainly the first Flag Johns made. Which is tricky, because that distinction is commonly given to THE Flag, at MoMA. But I think I have figured out that that is chronologically impossible. Johns may have started MoMA’s Flag before Short Circuit‘s, but he certainly didn’t finish it first.

Here’s the deal:

The date for MoMA’s Flag has always been in flux, but it has almost always been considered or assumed to be the first one he ever made. The disappearance from public view of the Short Circuit flag after 1962 greatly facilitated this conclusion.

And Johns’ flag painting creation myth sounds enticingly specific and maddeningly unverifiable: “One night I dreamed I painted a large American flag, and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” In a 1966 interview with Alan Solomon, Johns made it sound like there were other, or multiple stories about the origin of Flag paintings. Even though Solomon had exhibited Short Circuit as Construction with J.J. Flag in 1958, he talked about the MoMA Flag as if it were the first.

It’s dated 1954 on the back, but it’s currently officially listed as 1954-55.In his 1977 catalogue, Michael Crichton puts the date where Johns “argued” the painting “was done,” in 1955. But he also adds this story:

Recently, someone noticed that the collage included newsprint from 1956, and the museum wanted to change the date accordingly. Johns stated that the picture was damaged in his studio in 1956, and that he repaired it that year, but that the painting was still properly dated 1955.

It’s the perfect example of the phenomenon that drew Johns to the flag in the first place: it’s a thing which is “seen and not looked at, not examined.” That someone, it turns out, was not a scholar, curator, or conservator, but an unidentified museum visitor, who spotted the date clearly through one of the white stripes, after the painting went on public view. [Alfred Barr had leaned on Philip Johnson to buy Flag for the Modern in 1958, but Johnson didn’t get around to giving it until 1973.]

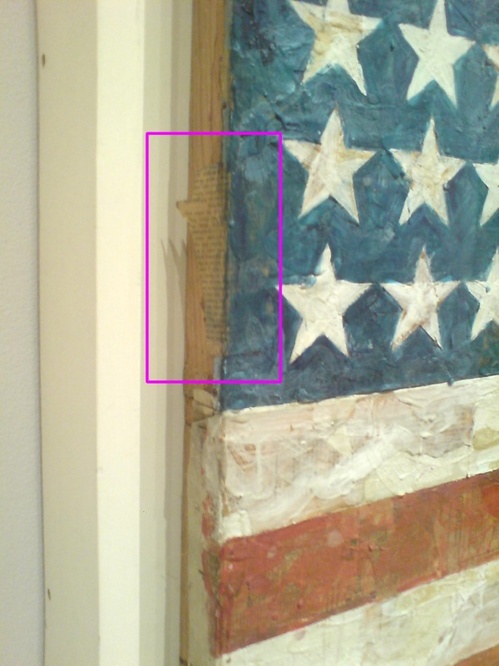

I had this anonymous amateur sleuth in mind when I went to examine Flag in the latest reinstallation of MoMA’s Fourth Floor galleries. [Which, hello, it’s been almost a year now? Nine months? Have we talked about this? There is much of interest, a quiet revolution, even, in various places. I’ll just start by pointing out the subtle but highly persuasive inclusion of mid-50s Rauschenberg, Twombly and Johns in one gallery. It’s the future of the past, and it’s here today. Check it out, and we’ll come back to it.]

After using Google Books to pretty much instantly identify a visible fragment of collaged text on Johns’ Map as coming from A History of Orgies, I wanted to see if Flag had any tasty, trackable collaged elements. And guess what:

Right there on the side of the blue field, clear as day–clearer than the carefully unpainted orgy page in Map, even–is a torn piece of newspaper. It’s not tacked on, or peripheral; it continues under the blue and the stars, which show no obvious signs of reworking.

Thanks to DP for taking this clean shot for me after I found out my camera phone pix were too blurry to decipher.

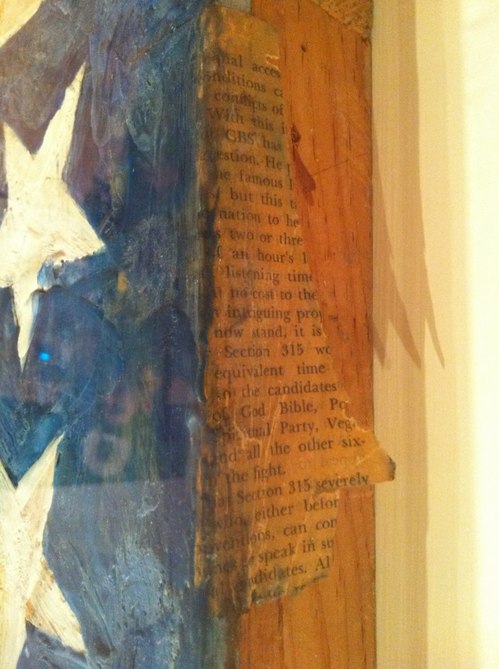

The piece is upside-down. When you flip it over, you can see the text, less than one newspaper column wide: “access…conditions of…With this in…CBS has…an intriguing prop–…Section 315…equivalent time…of God, Bible, …Spiritual Party, Veg… and all the other six…”

This time, I threw the text into the NY Times archive search. “Section 315” and CBS were the key; this turns out to be a story about one of the first controversies involving television and political campaigns. CBS and other broadcasters had filed a complaint about Section 315, better known as the Equal Time Rule, an FCC regulation that required TV stations to give all candidates and parties equivalent amounts of coverage or access to the airwaves.

The complaint mentioned how, in addition to Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson, the 1952 presidential election had candidates from 16 other parties, including, reported the Times:

the American Rally, the Christian Nationalist party, Church of God Bible Party, Constitution Party, Greenback party, Poor Man’s party, Progressive Party, Prohibition party, Republimerican party, Socialist Labor party, Socialist Workers party, Spiritual party, Vegetarian party, and Washington Peace Party.

Though the text doesn’t match exactly, the list began to circulate with coverage of CBS’s Sec. 315 complaint. The date of the Times story was May 29th, a week after the Stable Show closed.

In his footnote discussing the dating of Flag [p.66], Crichton quotes a warning from the artist himself that

certain early works include collage elements that are old–much older than the paintings themselves–thus obviating entirely such direct methods of dating.

Except not entirely. Because though Johns could have held onto that May 1955 newspaper scrap for any amount of time before using it, the one thing he could not do was use it before it existed. So the blue field of stars on MoMA’s Flag was not painted before the end of May 1955.

And before the end of the first exhibition of Johns’ uncredited Flag, shut behind a painted door in his partner’s combine.

Though it’s tempting to imagine Johns waking up during the Stable Show, having dreamt of painting a large Flag and getting right to it, that single visible scrap does not help connect Flag to Short Circuit for the very reasons the artist warned about. But the possibility is there. A closer, more systematic examination of the newspaper used in Flag may yield further evidence for pinning down the date and method of its making.

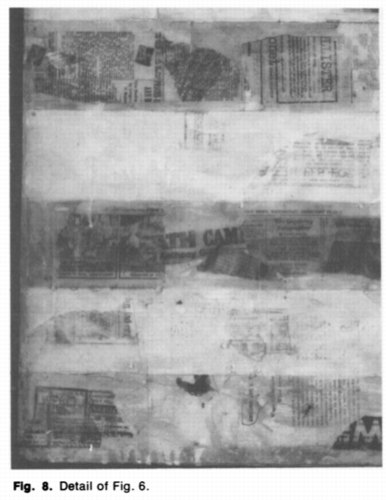

And then there’s the news on the paper itself, a finer-grained embodiment of the tension Johns’ Flag generated, which Fred Orton called “a perpetual oscillation between subject and surface.” Orton devotes five or so pages in his 1994 book, Figuring Jasper Johns, to the textuality, or visible/legible newsprint fragments of Flag, concluding that they amount to a political stance about the trivial populism of patriotism. And John Yau has written about the texts as well, though I have to dig up my copy of MoCA’s 1992 Hand-Painted Pop exhibition catalogue for that. But otherwise, I can’t find any scholarly discussion of Johns’ text since 1977, when Joan Carpenter argued for the significance of this “veiled collage” in her Art Journal paper, “The Infra-Iconography of Jasper Johns.” And her infrared detail shots are the only such images I can find anywhere.

infrared photo detail of Flag showing comic strip, classified ad, and “Death Camp” headline, from Joan Carpenter’s “The Infra-Iconography of Jasper Johns, via CAA

I assume MoMA has complete infrared or x-ray imagery of Flag, though none is publicly available. But I would think that matching up scraps to the digitized archives of the newspapers and magazines Johns used would be, for a computer, something just shy of trivial. But the data-based account of Flag‘s origin that might emerge from such analysis might be too at odds with the deeply subjective dream story that was once floated by the artist–and which is still preferred, so far, by the art world at large.