How much sense does this not make? People buy the sheets from Félix Gonzalez-Torres stacks at auction, on eBay, and at various artist book & ephemera dealers, and it just seems…what’s the word here? Hilarious? Sad? Stupid? Embarrassing? Ridiculous? Wrong? Inexplicable?

Well, no. There’s an easy explanation. People sell Félix posters because they want money. And people buy them because they are for sale.

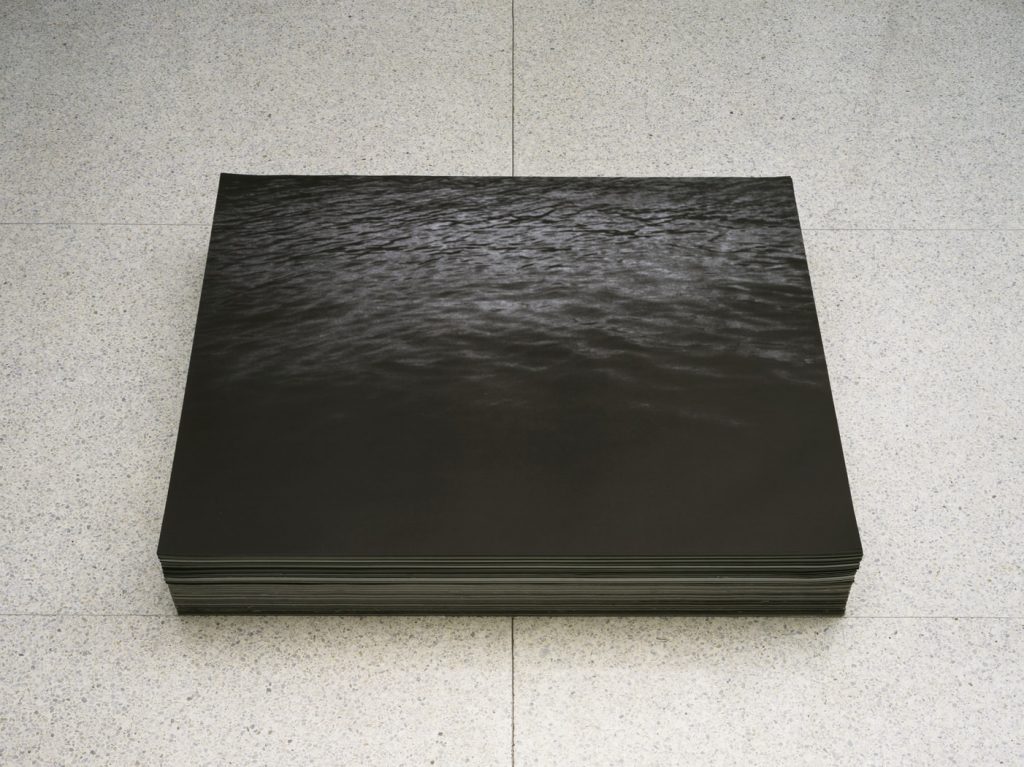

Félix made his first work that includes a stack of paper in 1988, and his first to consist of a stack constantly replenished with “endless copies” in 1989. Then there was a burst of stacks in 1990. By the time of his death in 1996, the artist had produced 47 stacks. Four were declared after his death to be “registered non-works.” One consisted of rubber doormats, which are not to be taken. One consists of an edition of 200 signed, silkscreen prints which together comprise a single stacked work, which are not to be taken. One was an edition of 250 of which 89 were sold separately, and the remaining 161 were sold together as a stack, which are not to be taken. The first one, it is not clear whether they can be taken. One is made of little passport-sized booklets, which can be taken. So that makes 38 stacks made of posters infinitely replenishable with endless copies. Along with a registered non-work stack created with Donald Moffett, three stacks were collaborations with another artist, who provided the image or text: Michael Jenkins, Louise Lawler, and Christopher Wool.

A part of the intention of the work is that third parties may take individual sheets of paper from the stack. These individual sheets and all individual sheets taken from the stack collectively do not constitute a unique work of art nor can they be considered the piece…its uniqueness is defined by ownership.

So these are not artworks. Or, they’re not the artwork. But they are something of value, even though they are free for the taking in an endless supply. And people trying to explain and justify the value–or the price, really–use paradigms that the artist himself critiqued, rejected, and sought, to some extent, to undermine. Sellers, including auctioneers like Wright who know what’s up, invoke an edition model, calling sheets “original” “prints” and “lithos” from “an unknown edition size.” This framing resonates with the investing community that has grown up around mass limited editions from print mills like Murakami and Hirst, Kawsian art toys and artist-designed skatedecks, and even Richter-style “facsimile objects.”

Rago, an auction house whose business is liquidating New Jersey’s vast collections of silkscreen editions assembled in the 60s and 70s, gives the sheets made-up names like “Untitled (water ripples)” and “Untitled (The Show is Over)”, and gooses the provenance with statements like “Created originally in 1993 for the Printed Matter exhibition at Dia.”

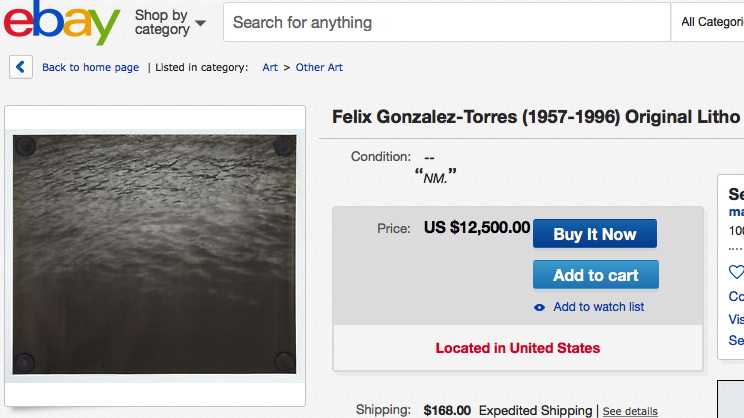

One eBay seller’s allusions to photography and rare book connoisseurship to justify a $12,500 asking price for a single sheet because it was taken from “the original piece” during a gallery show “in October, 1991,” have not gone unchallenged:

Please note that I have received some comments about this one… that is, since it was conceived of as an open edition, there are numerous ones out there from other exhibitions, and possibly a reissuance from the estate.That could be true, however, the original litho is a “first” printing; subsequent printings are of a subtlely diiferent (sp) size, color, paper, etc. This makes the first edition the most coveted, and hence the valuation.

Félix wanted as many viewers as wanted them to take sheets from his stacks for free, but this turns out to be not the same as free to obtain or endlessly available. They’re not all in publicly accessible collections. They’re not always on view, and they’re probably not close by when they are. So the constraints and complications of getting in a room with the Félix stack you want have real costs, and the way we weigh these costs against the desire to possess a thing is called money.

Then there’s the reality of the work itself, the stack whose “uniqueness is defined by ownership.” The artist’s certificates also say “The owner has the right to reprint and replace, at any time, the quantity of sheets necessary to regenerate the piece back to the ideal height.” There’s a concept worth studying in a work doesn’t just exist at various heights, but that depletes and is regenerated. If you find that dissertation, please lmk. What jumps out to me is the apparently fundamental link between uniqueness and authenticity and ownership, and the dependence of that existence on a right, not a responsibility.

For all the freedom and openness and sharing of Félix’s work, it rests on a foundation of rights granted to collectors, not obligations assumed by stewards. The market for sheets is thus the trickle-down effect of these private decisions that make stacks scarce through unavailability.

Could the artist’s wishes be better served by adapting his stacks to the digitized world he didn’t live to see? What if the Félix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation made all of the stack sheets available for download and individual printing? It’d be several kinds of complicated, I know, but it wouldn’t disrupt the existence of “the piece,” the uniqueness of which, remember, is defined by ownership. [Having recently pulled out around 100 sheets I’ve collected over more than 25 years, I can say this is not an obviously great idea; stacks vary in size, paper type, and finish in ways that DIY printouts will inevitably get wrong, and the artist’s generosity for everyone else’s shitty reproduction of his work will be sorely tested.]

Letting sheets loose in the wild will result in large-scale printing and distribution, probably at poster-scale commercialization. But a line in an eBay auction seems to indicate this is already happening.

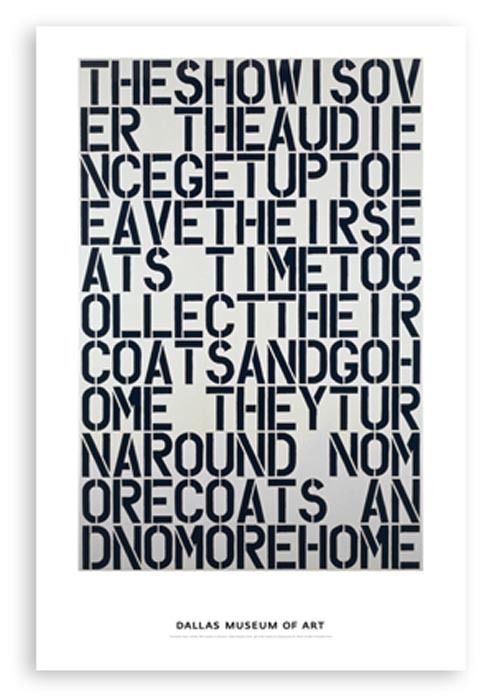

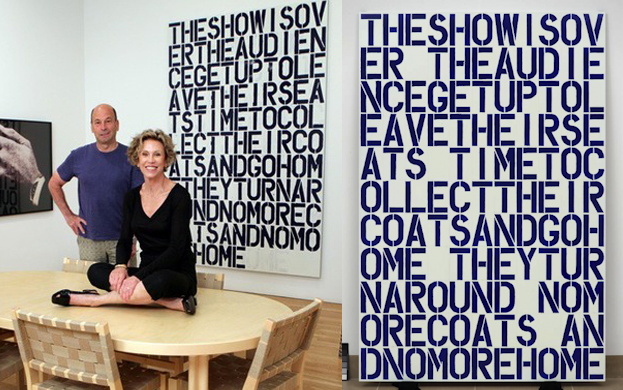

After comparing it to a poster that sold for $750 on artnet, the seller of this $1200 poster “by Christopher Wool & Félix Gonzalez-Torres” notes, “NOTE this is an original edition from the Dallas Museum’s run and not from China.” But something ain’t right. The dimensions of the Wool&FG-T sheet are 37×55, and this one from Dallas is 24×36. Also, there’s a giant border, and it says Dallas Museum of Art on the bottom. Also, the letters don’t line up. Because this is a poster of a painting, a painting [right] the DMA acquired in 1991. Meanwhile, the related painting that became the stack is hanging [left] behind Thea Westreich and Ethan Wagner. They gave it to the Whitney in 2014.

Isn’t this the real source of the Felix stack flipper problem: hypeboys looking for cheap Wools? And at hundreds to thousands of dollars a pop, wouldn’t YOU set up a #ChineseWoolMill to meet their demand?

If there is such a thing as capitalist karma, it comes in the form of Erika Hoffmann, the Berlin collector who, with her late husband Rolf, bought the Wool/Gonzalez-Torres stack. In March she donated it, along with her entire collection, to the Dresden State Art Collection. It will become one of the most public and publicly available stack pieces of them all.

[This writing of this post was delayed several days by the outraged consideration of the vast preceding and ongoing corruption of the president, and it took place amidst the anguished, mounting fury at the systemic policy of terrorizing and torturing children and families seeking asylum from perils that drove them to flee their homes. The solace of art has its limits.]

A COUPLE OF DAYS LATER UPDATE: I swear I wasn’t planning to do this, but then someone on Twitter feared it was coming, and so it had to happen.

“Untitled” (Ross in L.A.) in DC is now on eBay. [update: it is gone.] It comprises an original Félix Gonzalez-Torres offset print acquired from the National Gallery of Art, and a full-scale, signed, stamped, and numbered certificate of authenticity. It is available in an edition of 2. [update: it is not.]

previously, related:

“Untitled” (Crystal Bridges), 2015–

“Untitled” (ArtEverywhereUS)

on the stack as medium, I loved this for annoying me so much: When Form Becomes Content, or Luanda, Encyclopedic City