Ian at Water Cooler Games has been writing about an incident at Slamdance. Seems the founder of the alt-alt festival yanked Super Columbine Massacre, a charming -sounding RPG that tells the tale of some innocent, young, all-American scamps, from the Slamdance Guerilla Gamemaker Competition.

At first, the line was extreme sponsor displeasure with having a Columbine-themed title in competition. [I mean, just look at what it did to Cannes and Cannes. No one’s ever heard of them again.] But now it turns out that it was really just Slamdance president Peter Baxter’s own call in anticipation of possible sponsor displeasure–or else his own distaste for the game itself. Either way, it sounds like crap.

There’s a lot of heated discussion among gamers and developers about the artistic merits of games vs their “mere entertainment” value. I think that’s ridiculous and beyond discussion. Games have as much claim on “art” as film does. If anything, the nexis of creative, literary, and narrative innovation has shifted to games and away from almost any other medium I can think of at the moment.

This just sounds like a dumb-ass move by a blindered geezer whose vested interests are too tied up with the establishment. Exactly the kind of rejection and narrow-mindedness that spurred the creation of Slamdance in the first place. The only proper response, obviously, is for gamers to break off and make their own damn festival in response.

Then after this happens seven times, the Matrix collapses and has to be restarted from scratch.

Slamdance: SCMRPG removal was personal, not business [watercoolergames.org via boingboing]

the always awesome Greg Costikyan’s reponse, plus they posted the game: SCMRPG: Artwork or Menace? [manifestogames.com]

Previously: Gus Van Sant’s Elephant is part of the canon around here. Read my interview with producer Dany Wolf about the in-movie homebrewed video game based on Gerry.

Also: the art-movie-as-video-game-at Sundance, Gerry/video game connection.

1/9 update: Costikyan reports that to date, five gamemakers have withdrawn their titles from the festival. Yesterday, it was just one.

Category: making movies

Nam June Paik’s Early Work

I used to live downstairs from Nam June Paik. I was too starstruck to ever talk with him at length, but we had friendly chats when we’d see each other in the stairway of our Little Italy loft building.

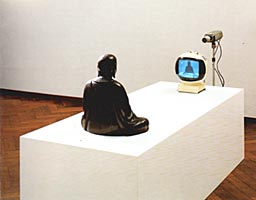

Once, I did manage to tell him how much I admired his pieces in the John Cage show that was going on over at the Guggenheim SoHo [“Rolywholyover: A Circus,” still one of the most brilliant and exciting museum exhibitions I’ve ever seen. Incredible catalogue, too.] My favorite was and is TV Buddha, a nearly perfect conceptualized work comprised of a carved Buddha statue , a video camera, and a television. The statue sits enlightened and silent, endlessly watching itself on the screen.

TV Buddha is made even better by the allegedly offhand way it was created, as “wall filler” for a 1974 gallery show in New York, though I wouldn’t be surprised if Paik was just being reflexively modest when the work was praised.

He made many versions and variations on the TV Buddha theme over the years, and I’d also imagine it could come to feel like a zen trap, a polite rut, especially for an artist whose work betrays an abiding affection for baroque dadaism and psychedelic media cacophony. TV Buddha feels like a kind of contemplative road less traveled.

The road Paik took instead, was the one he named, the Information Super-Highway, which was signalled by another seminal early piece, the 1973 TV show/control room happening/video art work, Global Groove. Produced with John Godfrey at WNET in New York, Global Groove is at once freakishly prescient and contemporary, and hilariously of its time.

It opens with the bold promise that we’re living with right now: “This is a glimpse of the video landscape of tomorrow, when you will be able to switch to any TV station on the earth, and TV Guide will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.” Which is promptly followed by a groove challenged pair of disco dancers and every psychedelic FX trick in the 1973 TV producer’s book. It’s at once funny and sad to realize Global Groove‘s aesthetic has become the lingua franca of Manhattan’s public access TV world. Hell, it’s probably the same mixing board Paik & Godfrey used.

Paik’s TV sculptures and giant video walls which are so popular/populist with museums and lobby decorators feel like continuations of Global Groove‘s groove, but it doesn’t scale. Paik foresaw our TV-webby mediascape and reveled in it; I just wish and wonder if somewhere in Paik’s mature-to-late career, away from the bombastic over-commissions, there’s some underappreciated body of work that might enlighten us as to how we can live in this worldwide web.

See a photo of the first TV Buddha and watch the first few minutes of Global Groove on Mediakunstnetz.de [mkz]

There’s some Paik-related material on YouTube, but not as much as you’d hope [youtube]

The Making Of That Honda Rube Goldberg Commercial

It’s got a bit of that smug, self-congratulatory air that always seems to come through in behind the scenes films for commercials [I’m thinking in particular of the Sony Bravia bouncing ball ad guys]. But still, it’s all we’ve got, and it’s kind of fascinating.

Conceiving, speccing and constructing the sequence for “Cog” is hard enough, never mind actually shooting it in one, clean take. Here’s the commercial again.

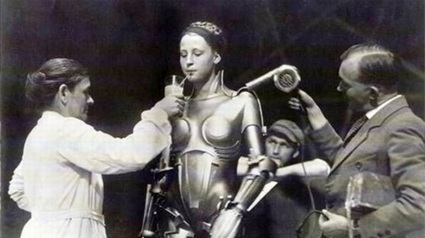

Wow. Metropolis. Kino. Murnau.

“At last we have the movie every would-be cinematic visionary has been trying to make since 1927.” – AO Scott, NYT

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (Restored Authorized Edition) DVD [amazon, image via coudal]

VV: Christine Vachon, Sellout

She insists that as “independent film keeps getting bigger, I want to make it small again,” only to confess later during a casting meeting for the movie Infamous that (her italics) “there is nothing more important than sitting in a room with Julia Roberts.”

A more forthright book would’ve taken the indie community to task for selling its soul to the studios and jumping into the sack with award-hungry stars.

Not that the Voice is the fount of filmic credibility lately, and I’m not one to begrudge someone’s weariness of artistic suffering, but for some reason, I did kind of hope Vachon would always be a scrappy pioneer. Or that she’d keep fighting for new generations of filmmakers not her own, which seems to be the root of the sellout issue.

Review: Christine Vachon’s A Killer Life [villagevoice]

On Robert Altman

After memorizing The Player, the visceral Short Cuts got me hugely excited for Pret a Porter. Oops. At the time, I had to learn for myself what Pauline Kael knew long ago: she “joked about his fertile seventies output that every other film was a masterpiece and that she wished she could skip the ones in between.”

The quote’s from David Edelstein’s remembrance of Altman for NYMag. It’s worth a read. [nymag]

Meanwhile, Tony Scott reminds me that that incredible Lily Tomlin-Meryl Streep schtick at the Oscars last spring was exactly the kind of offhand-yet-impossible tour de acting force Altman was able to capture. or coax. or catalyze in his films. [nyt]

And then there’s a real leaping off point. David at GreenCine points back to Matthew Zoller Seitz’s Altman Blogathon Weekend last March, in anticipation of the long overdue Altman Oscars.

Theresa Duncan’s own remembrance of McCabe and Mrs. Miller is awesome, especially the anecdote at the end about Leonard Cohen finally coming around to liking the film that he reluctantly licensed his music to.

BLDGBLOG On Ballard On Film

Geoff de BLDGBLOG has a long interview at the JG Ballard megasite Ballardian.com in which he discusses [what else] Ballard & architecture [actually, a lot else. the dude thinks in eyepopping paragraphs]:

What do you think of Cronenberg’s Crash?

It’s alright — but I’m not a big fan. It takes itself way too seriously, for instance, and ends up just boring the shit out of everyone. I think it was miscast, badly paced, and not explicit enough about its themes. As it is, the movie appears to be about a bunch of dull and uninteresting Canadians who get into a car accident one day and end up wife-swapping. Yet, having said that, the movie isn’t funny at all.

…

Which Ballard book would you like to see filmed?

You’re going to think I’m out of my mind, but I’d like to see Steven Spielberg direct The Drowned World — as long as he didn’t add any kids to the screenplay. Or Danny Boyle film Concrete Island. Or, for that matter, Wong Kar-wai could film Concrete Island, in Chinese, set in Hong Kong. Or Shanghai — a nice bit of Ballardian symmetry there.

…

Do you feel that Blade Runner’s an overrated text as far as architectural criticism is concerned? It always gets name checked, but one thing I feel it missed was the ‘invisibility’ of new technology. It’s probably the last of the old-school dystopian sci fi films, where the city itself was a major character, imposing and present…

As an architectural film, yes: I do think Blade Runner is over-rated. Even as a film about urban design or the urban future. But as a film about the overwhelming sadness of being alone in the world – in that regard I think it’s unbelievable, and deserves its reputation…

Also noteworthy: repeated uses of the world, “whilst.”

The Politics of Enthusiasm: An Interview with Geoff Manaugh [ballardian via bb]

Gears For Fears

Jason posted a link to a preview for the video game Gears of War that uses Gary Jules’ and Michael Andrews’ acoustic cover of Tears for Fears’ “Mad World” as the soundtrack.

The original music video for Jules’ version is a favorite of mine. Even though the cult of Michel Gondry really bugs, I’m mostly a fan, and I’m a sucker for a well-done tracking shot, especially an outdoor one that can’t involve hundreds of takes because it relies on daylight.

That, and T4F allows me to relive my early teen mopiness and recall those days when my biggest dilemma was not living in London or LA.

Background on the Gondry video; a 2004 Chris Norris review of the video for the NYT. The Gondry video is on the Director’s Cut DVD for Donnie Darko, which restores some of the music from the Sundance version of the film.

What Requiems For A Dream May Come

It feels like ages since I’ve posted about actual moviemaking around here. I was a fan of Darren Aronofsky’s Pi, and a fleeing refugee from the theater of Requiem for a Dream, but I have to give props to his vision and instinct for making his new film, The Fountain:

No matter how good CGI looks at first, it dates quickly. But 2001 really holds up. So I set the ridiculous goal of making a film that would reinvent space without using CGI.

…

Aronofsky and his crew flew to Central America to consult with legendary Mayan experts like Moises Morales Marquez, who has guided scholars through the ruins of Palenque for half a century. They made a pilgrimage to the Guatemala location used by George Lucas for the rebel-base scene in the original Star Wars film, high in the crumbling temples of Tikal.

…

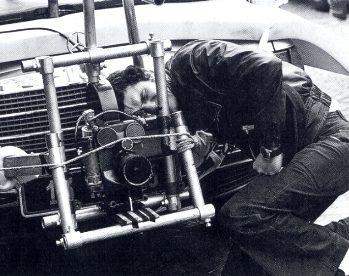

The microzoom optical bench furnished Aronofsky’s film with something neither a computer nor an old-fashioned matte painter could deliver – chaos, in all its ultra high-definition fractal glory. “The CGI guys have ultimate control over everything they do,” Parks says. “They can repeat shots over and over and get everything to end up exactly where they want it. But they’re forever seeking the ability to randomize, so that they’re not limited by their imaginations. I’m incapable of faithfully repeating anything, but I can go on producing chaos until the cows come home.”

Palenque?

Steve Silberman interviewed Aronofsky for Wired [wired via bb]

Non-Sensical Non-Site Non-Art?: Smithson’s “Hotel Palenque”

Curator Nancy Spector described Robert Smithson’s Hotel Palenque, which the Guggenheim acquired in 1999 from the artist’s estate [controlled by his widow Nancy Holt and represented by James Cohan Gallery] this way:

Hotel Palenque perfectly embodies the artist’s notion of a “ruin in reverse.” During a trip to Mexico in 1969, he photographed an old, eccentrically constructed hotel, which was undergoing a cycle of simultaneous decay and renovation. Smithson used these images in a lecture presented to architecture students at the University of Utah in 1972, in which he humorously analyzed the centerless, “de-architecturalized” site.

Extant today as a slide installation with a tape recording of the artist’s voice, Hotel Palenque provides a direct view into Smithson’s theoretical approach to the effects of entropy on the cultural landscape.

Smithson’s lecture combines deadpan delivery with absurdist architectural/archeological analysis of a contemporary ruin, a critique–or a spoof–of the kind of academic jargon-laden travelogue usually reserved for slideshows of “real” architecture like the nearby Mayan temple complex.

The lecture is available in several formats: the Guggenheim version was included in the recent MoCA/Whitney retrospective; an illustrated transcript was published in Parkett #43 in 1995; and the incomparable UbuWeb has a 362mb film of the 1972 event for download. [update: uh. ] There was even a “cover version” “performed” by an artist last year in Portland.

But re-viewing the “original” really makes me wonder. The differences between various posthumous incarnations and interpretations of the “Hotel Palenque” lecture seem significant enough to make me question what Smithson actually intended for the lecture, how it was originally received, how it has been contextualized today, and if it is even a “work” at all.

The medium through which art is experienced inevitably influences its perception and interpretation. For an entire generation while it was submerged, the Spiral Jetty “existed”–or was experienced–only through memory, history, text and photo documentation, and, importantly, the artist’s own “making of” film. Once the actual work started re-emerging in 1993-94, its experiential aspects have shifted; now The Visit, the spatial situation, environmental conditions and entropic forces at the site, and the interplay between the Jetty‘s manifestations come to the fore.

Similarly, Palenque is consistently described in hindsight, through the sophisticated conceptual contstruct of Smithson’s writings, but to watch it, Palenque actually sounds like a dorky, rambling joke, more parody than pronouncement. The only real jargon he uses are “situation” [in the architectural sense] and “de-architecturization.” Otherwise, the real/only humor comes from the juxtaposition of his blandly weighty assertions of importance and photos of torn plastic roofing, piles of bricks, and a room propped up by shaky-looking poles [“this is how we approached the site; our car is right there, see between those two columns?”]

The lecture is described as funny, but the only laughter I could hear sounded nervous, or at least tentative. And without knowing anything of how the lecture came to be, and how it was received and reviewed at the time, I can’t help but imagine that some people, like Smithson’s hosts, or his audience, might have felt like the butt of some smart-alecky New York artist’s practical joke. Overall, I guess I find it hard to reconcile Smithson’s sophomoric performance with his hallowed reputation; the lecture fits more neatly with his early, critically challenging “high school notebook doodle” drawings of busty angels than it does with his heavily theoretical Artforum articles.

[It’s worth pointing out that Smithson’s photo/slides, on the other hand, feel very resolved and coherent. I was repeatedly reminded of Gabriel Orozco’s photos of “found” sculptural scenarios and moments, as well as of Smithson’s own Passaic series and other photographs. We have a favorite photo, a top-down shot of a pile of bricks, that he did after returning from the Yucatan; the man does have a way with rubble.]

But the most problematic issue about Palenque could be a non-issue for almost any conceptual artist, but it seems paramount given Smithson’s own ideological concerns with the gallery/museum space and system: to what extent should the lecture be considered “performance” or a “work of art” itself? The Guggenheim’s version of Hotel Palenque consists of a slideshow and an audiotape, which plays in polite form in a museum gallery.

But before/besides that incarnation, the lecture “existed” [or was experienced] as a filmed version, made with a handheld camera seated somewhere in the crowd in Salt Lake City. Smithson himself is off camera, and several times, the slides themselves are, too. The film is a bootleg only to the extent Baltimore artist Jon Routson‘s self-consciously askew video recordings of movies are, which is to say, “not at all.” The amateurish, sometimes forgetful framing and the handheld jitters heighten the experiential, audience perspective. There’s one passage where the camera bobs up and down in synch with its operator’s breathing. These are all central, even overwhelming, elements of the Palenque film, and they’re utterly absent from the “institutionalized” version, just as Smithson’s delivery is lost in the Parkett transcript [a version which no one would mistake for anything but documentation or reportage.] It’s enough to make me wonder just what the Guggenheim bought–or just what the Smithson estate sold–with Hotel Palenque which, by 1999, had to be one of the few significant “pieces” or, less problematically, holdings, left in the estate.

The Guggenheim also bought, at the same time, nine slides of Yucatan Mirror Displacements, iconic images of landscape interventions which Smithson made on the same 1969 trip. But these slides–which illustrated an Artforum essay and are widely reproduced in print–have never existed to my knowledge in artist-sanctioned formats like traditionally editioned prints. I’d be very interested to see documentation or scholarship on this question–which is also a fancy way of saying I have no idea or direct knowledge at this point–to see just how closely Smithson’s definition of defined, purchasable work jibes with notions operative in 1999 among art dealers and museum acquisition committees.

Because there have already been plenty of cases where Smithson’s ideas, his works, and his estate’s interpretations of them sometimes seem out of synch. Had Smithson not died suddenly and tragically the next year would this offhand-seeming ramble be treated with even a fraction of the reverence it has received? And if there had been more sculptures and clearly identifiable “work” to sell in the estate when Smithson’s star re-emerged in the late 1990’s, would Hotel Palenque ever have made it out of the archives and into a major museum’s collection?

Previously: UT gov’t decides to clean up the Jetty site

Nancy Holt floats the idea of “restoring” the Jetty

“The Spiral Doily”: What if sprawl is the real entropy?

Other Smithson-related posts on greg.org

Elsewhere: Brian Dillon’s appreciation of the lecture as artform in Frieze

51 Birch Street: Home, Movie

After his mother died and his father quickly remarried, filmmaker Doug Block went to visit his childhood home for the last time, as it was being emptied and put up for sale. He ended up spending two years making 51 Birch Street, an extensive examination of his parents’ lives and relationship. The film opens in NYC and LA Oct. 18:

… I walked inside and saw our entire family history being packed away in boxes and it all hit me like a punch in the stomach: although I hadn’t lived there in over 30 years, on some very primal level I still thought of this place as my home.

It soon became apparent that my father, who never talks about himself, was not just willing but was eager to talk. And that my camera was facilitating the conversation by allowing me to ask the difficult questions I could never have asked otherwise. I saw a unique opportunity to get to know my father better, so I decided to keep coming back.

51 Birch Street website, including Block’s documentary-centric blog [via kottke]

Still Indie At 40?

It’s funny that–oh, wait, no, it’s depressing, no, it’s funny, no, it’s–someone like Mary Harron who has done some good films has also done some great television, but somehow it comes off sounding like a bad thing.

I’d love to see any of the filmmakers in this article try taking the Soderbergh Bubble approach and attempt to break new business and economic ground with their films, too; they sound somehow trapped in a paradigm not entirely of their own making.

All that said, John Jost, whoa.

Survival Tips For The Aging Independent Filmmaker [nyt]

Wednesday In The Car With Claude

Now the story can be told. It’s interesting how long it takes stuff to bubble across the Internet. A recent spate of blog discussion of Claude Lelouch’s 1976 cult short film, C’etait un Rendezvous was prompted by the film’s mention in GQ this month. Similar waves of discovery and amazement accompanied, in reverse chronological order, the pairing up of Rendezvous with a follow-along Google Map, and a couple of years back, the film’s triumphal re-emergence on DVD after lingering for decades in bootleg-VHS obscurity.

But in the spring [Mercredi 24 Mai 2006, precisement], Lelouch took some French TV dude along to re-travel the route and talk about the making of the film. The result: answers for a lot of the rumors, questions, and legends that accumulated around the film. Too bad no one bothered to ask Lelouch before now. [But then again, my point is, I’m kind of bummed that I’m only finding this out now, four months after it was shot.]

1) Lelouch was driving

2) his Mercedes 6.9 [which he still has, which is one of my alltime favorite cars]

3) because the pneumatic suspension would produce a much smoother image.

4) The Ferrari audiotrack was dubbed in afterward.

5) The woman at the end is his wife.

6) The whole thing was done on a whim, after shooting something else with a car-mounted camera, and using a leftover magazine of film.

My favorite line of the whole interview: “Yes, I was scared. I was scared of running out of film.”

C’etait un Rendezvous The Making Of {youtube via jalopnik]

French discussion and transcript from April [axe-net.be]

In-Game Developer Commentary, In-Game Video Production

Andy has some video of some in-game developer commentaries that are included in the Half-Life 2: Episode One. They’re a cross between a typical DVD director’s commentary track, hyperlinked footnotes, and a first-person video tour. Fascinating.

Perhaps the coolest, though, is a commentary where they show how an in-game video projection–where a game character’s talking head appears on an in-game monitor–is made. Turns out the clip is actually “shot” “live” in a walled off part of the game, and “broadcast” to the monitor. It’s like in-game machinima or something, which is a bit to recursive for me. I think my head will explode.

Half Life Developers’ Commentary [waxy.org]

What If It Was Carson Daly? Would You Hate Him?

You could make a really good-looking movie right now for ten grand, if you have an idea. That’s the trick. I was watching Alphaville this weekend, and I’d love to do like a ten-minute version of Alphaville here in Manhattan. It’s so easy now. I don’t know what the ultimate result of that will be—whether you’ll see a sort of a film version of iTunes, where you can access things that have been made independently by people…

But then the question is—whose vetting process is this, and who are these people? …

I don’t know where the middle point is—“I can’t find anyone to vouch for the legitimacy of this thing that somebody’s asking me to download”—and access that’s being controlled by a bunch of people who, it’s possible, if you met, you’d actually hate.

– Steven Soderbergh shooting the breeze with Scott Indrisek in the August issue of The Believer and on the Wholpin DVD, vol. 2 [via greencine]

Related: Carson Daly-backed Online Video Site* Launches [fishbowlny]

* funded by Half Nelson producer Jamie Patricof, btw