You know, someday, I’ll go to Artforum’s homepage, and those sidebar links to the Chris Marker photographs of May Day protestors in France [“In this new series, he re-presents the present as, effectively, already past,” or as they say in French, la plus ca change…] and the Gary Indiana piece about Richard Linklater [aka, “the Dostoevsky of movie dialogue,” which may be a slam disguised as a compliment] will be gone.

It’s unlikely, but hey, it could happen!

Category: making movies

The Residents, The MoMA, & The River Of Crime

Our lives are constantly surrounded by unseen streams …numerous, invisible rivers composed of love, power, success, pain …all that we detest and desire. Some we navigate with ease, some we seek forever …and some are simply whirlpools, spinning us into oblivion.

In conjunction with the release of their newest album [sic], “River of Crime,” and in anticipation of their MoMA screening/retrospective in October, pioneering NYC art punk tech band The Residents have launched a video contest, er, a “community art project.”

Create a video to accompany the 1:30 audio track they provide, and send it in. The Residents and MoMA curator Barbara London will pick 20 to upload to YouTube, and from there onto a MoMA screening and exhibition on the museum’s site.

I’ve had a MoMA screening myself; I highly recommend them.

See details and downloads for the River of Crime Community Art Project [residents.com via e-flux]

Inspired by 1940’s true crime radio dramas, “River of Crime,” was released in May as two blank CD-R discs that you fill up with secret downloads [residents.com]

I Still Get People Asking Me For Sofia’s Number

Usually, they’re slightly off-kilter but harmless fans, who seem to believe that if they can only get their pitch to their favorite director, they’ll make beautiful music together.

Turns out Wes Anderson has fans like that, too, only their names are Steely and Dan:

So the question, Mr. Anderson, remains: what is to be done? As we have done with previous clients, we have taken the liberty of creating two alternative strategies that we believe will insure success – in this case, success for you and your little company of players. Each of us – Donald and Walter – has composed a TITLE SONG which could serve as a powerful organizing element and a rallying cry for you and Owen and Jason and the others, lest you lose your way and fall into the same old traps.

that’s pure awesome on a stick.

ATTENTION, WES ANDERSON [steelydan.com via waxy]

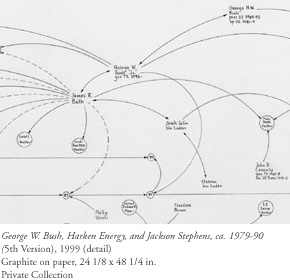

Conspirasyriana

This:

[philosophistry.com via mathowie]

reminds me of this:

from Mark Lombardi: Global Networks, Nov. 1 – Dec. 18, 2003 [drawingcenter.org]

in a good way.

The Re-Searchers

John Ford would probably be pissed at you if you read this article about him in the UK Independent, but go ahead, it’s worth the risk.

John Ford: Ford focus [independent.co.uk via rw]

There’s a 2-disc anniversary edition of The Searchers out, btw [amazon.com]

Waiting For Guffman Corbin Bernsen

Red Paper Clip Day could become an annual party, with residents encouraged to wear red paper clips as a Town symbol. The Town is in the process of designing a new logo which is to include a red paper clip.

– from The Citizen, Kipling, Saskatchewan, Canada, 06/30/06

Kyle MacDonald trades a role in snowglobe megacollector Corbin Bernsen’s next film to the town of Kipling.

One facet of the plan is to conduct auditions in Kipling for the part, perhaps as early as September.

MacDonald said he has discussed the idea with Bernsen, who has indicated great interest in the concept. MacDonald even hinted that the movie star and his family might become involved in the auditions and accompanying celebrations in some capacity.

“This is going to launch a cascading series of media events that will turn (yours and my) lives upside down,” MacDonald predicted to Roach.

one red paperclip [via waxy]

In other Kipling news, Kennedy-Langbank School had their Junior Drama Night on June 27. Coincidence?

The Making Of A Machinima Feature

Amazingly, Hugh Hancock has been making Machinima–movies created inside video games–since 1997. [If by “Machinima,” he means capturing playing sessions within user-created levels, core functions of the Doom game engine, then hasn’t everybody been making Machinima since 1997? But I quibble.]

What Hancock and his peeps at Strange Company have done is produce BloodSpell, a feature-length machinima film, which they’re releasing in 5-7 minute segments every week. There’s a production blog [on livejournal, which explains why I never saw it], and now they’ve published some more expansive Making Of articles as well. Here’s Hancock’s discussion of the 6-month creation of the animatic:

At this point, we started what was probably the most controversial part of BloodSpell’s development, and also the part that is, today, most crucial in ensuring we can meet our schedule – the creation of BloodSpell’s animatic.

For the uninitiated, an animatic is a storyboard, scanned in and converted to a video file, with voice laid over the top at approximately the pace of the finished film. It’s a handy tool to tell whether or not your film will work for your audience in its finished form.

In our case, our animatic was created by taking screenshots in Neverwinter Nights, based on a rough storyboard (and as you can see in the picture, I’m not kidding about the “rough” part – Ridley Scott I’m not). For each shot, we took either one or several shots of the expected action, then edited them together at about the pace of the film.

It was a mammoth project that rapidly gave us an idea of the scale we would be working at – the first draft of the animatic took from December 2004 to May 2005 to create, with either two or three people working from three to five days a week on it, as we created what essentially was a static version of the whole film.

In hindsight, I don’t think BloodSpell would be half the film it is today without the animatic. We went from shooting half a page a day, maximum, to shooting four or five pages of script per day by the end of the animatic’s production. It was through the animatic that we managed to find and iron out literally hundreds of problems with our sets and characters, and develop the toolset we use today to film. In addition, from the first draft of the animatic to the final shooting-ready draft, we added nearly 20 minutes of new plot, exposition, character development, and de-confusing.

BloodSpell: From Concept to Finished Scene Part 1 [via boingboing]

Strange As It Ever Was

“You may tell yourself: ‘He’s got some crazy dance moves.’ And you may ask yourself: ‘Toni Basil co-directed this?!'”

– Joe Tangari re Talking Heads 1981 video for “Once in a Lifetime,” directed by Toni Basil and David Byrne.

YouTube, via Pitchfork staff’s list 100 Awesome Music Videos (on YouTube)]

Alexander Calder’s Circus Film On YouTube

Fellow dadblogger sweetjuniper just posted the 18-minute version of Calder’s Circus on YouTube. It was made in 1961 by Carlos Vilardebo, and it’s been shown widely around the world–and in the lobby of the Whitney Museum–ever since. Since the Circus’s actual figures are now too fragile to leave the Whitney, the film usually serves as a proxy, providing a window into this crucial, early body of Calder’s work.

Calder’s fascination with movement and working with wire led him first to create wire sculpture ‘portraits,’ and later informed his creation of mobiles. But the popularity of le Cirque Calder in 1920’s and 1930’s Paris helped Calder form relationships with artists like Miro and Mondrian who were themselves extremely influential on Calder’s work.

Live performances lasted up to two hours and included twenty or more acts and an intermission. [The Calder Foundation’s website rather irrelevantly points out that Circus performances predate so-called “performance art” by several decades. The work is important enough not to try to stretch it so far beyond its obvious theatrical and puppet show precedents.]

A note about distribution-uber-alles, the Vilardebo film is at least the second filmed version of the Calder Circus. In 1953, the pioneering science filmmaker Jean Painlevé made Cirque de Calder, which exists in both 40- and 60-minute versions. But it’s Vilardebo’s later film–and the shorter version of it–which has gained the biggest audience.

If anyone know more about Painlevé’s version, or about the story behind the making of Vilardebo’s film–which, after all, was shot much later, when the artist is an older man, and when the Circus had grown too large to be transported in a trunk back and forth between New York and Paris–please drop me a line.

MoMA curator James Sweeney’s exhibition catalogue essay on Calder from 1951 gives an excellent explanation of the Circus in the context of Calder’s career.]

Bloghdad.com/The_War_Tapes

Deborah Scranton got embedded reporter credentials, but her documentary, The War Tapes was largely shot by US soldiers in Iraq using camera equipment she provided. She did much of her directing remotely via IM and email reviews of Quicktime dailies. Here’s ‘s a portion of ‘s discussion of a typical scene, where the troops guard a convoy of supplies being operated by Halliburton subsidiary KBR. The scene provides an indelible insight into the day-to-day situation the troops face, and the complexities that underlie every passing mention in the news about “IED’s” and “convoys”:

KBR sells the swag to the government (meals, haircuts, styrofoam plates for $20+ bucks a pop) and to the troops. There’s a great scene of soldiers packed into KBR’s amply stocked commissary after a hard day of escorting. They’re there to buy DVDs, Pringles, Becks beer, and soft drinks from KBR. Suddenly, you realize that every copy of “Armageddon” and every bottle of Mountain Dew was trucked in through the same hellish corridor as the cheese.

“The War Tapes” doesn’t tell us how the war is going, or speculate about the probability of success. Instead, it shows us how much blood and treasure is spent to deliver a single convoy of cheese to an American camp just a few miles outside of Baghdad. The implication is clear but unspoken: The Americans don’t control the main roads around key bases. The fight to keep Camp Anaconda supplied is a war unto itself.

Citizen soldiers, citizen media: The War Tapes [majikthise via robotwisdom]

Two of the soldiers, Sgts Jack Bazzi and Stephen Pink, were on Fresh Air last Thursday [whyy.org]

On Making Music For Prairie Home Companion

On WETA, the DC public radio station, Sunday night, Mary Tripp, the reporter for a program called Out and About, interviewed some of the musicians who performed in Robert Altman’s upcoming Prairie Home Companion.

The band members are used to live performance and to studio recording, so their perspective is at once professional and distinct. And given the subject of the film, it’s a relevant and interesting window Altman’s work process and life on his set. Garrison Keillor actively bugs, but the rest of the cast–and Altman and PT Anderson–are enough for me to overcome my PHC antipathy and be stoked about the film.

And even though they also wrongly bullied Rex over his Prairie Ho Companion t-shirts.

You can listen to the June 4 episode of Out and About for at least this week at weta.org [weta.org]

Through The YouTube Darkly

Has anyone ever asked Richard Linklater about the role A-Ha played in the development of Waking Life and Scanner Darkly. Just wonderin’

A-Ha: Take On Me [youtube]

update: I mean, I never thought I was very original to begin with, but still… And anyway, this is closer to Waking Life stylistically.

So maybe the better question is, has anyone ever asked the Beastie Boys about the role of A-Ha in the development of “Shadrach”?

Long Days Journey Into A Movie Theater

Like many people who join cults, my route to Kieslowski fandom and membership in the Church of the Dekalog looks a little goofy in retrospect. I was clearly seduced by the romanticism of La Double Vie de Veronique, not just within the movie itself, though there’s plenty there–but by the whole cinema-going experience:

I’d stayed an extra day on a sudden, unexpected business trip to Paris, moving from my work hotel to a dumpy 2-star, the St. Andre, in St. Germain. La Double Vie, it turned out, was screening in a little theater on the corner, and so I went that night, blind [so to speak.] Of course, I got more from the first, Polish half of the film, because I could read the French subtitles, while the second half blew by me. I had to wait a year or more for the US release to find out why Veronique was talking to that kitschy puppeteer.

But by then, I was hooked, and I joined the ranks of people who waited for Kieslowski’s true masterpiece, the largely unseen, 10-hour Dekalog to turn up at some festival or college cinematheque or wherever. Comprised of 10 1-hour-or-so episodes, it’s an easier moviewatching experience in some ways than the several-marathons-length films of Bela Tarr or Jacques Rivette, but it still meant reordering a couple of days’ schedules around the screenings.

Up until the back-to-back screening of The Cremaster Cycle at the Guggenheim, the longest films I’d watched were Sidney Lumet’s classic Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which I finally saw through twice after catching parts of it all week as I was running the projection booth at BYU. And that was only three hours [bah]…

…and Jacques Rivette’s 1991 La Belle Noiseuse, which clocked in at four hours. Of course, a good portion of that four hours involved the nude artist’s modelling talents of Emmanuelle Béart, so not as much watchchecking as the runtime might lead you to expect.

Anyway, this is all by way of setup for a link to Dennis Lim’s report of seeing the even more mythical Rivette film, the original 12.5-hr version of Out 1: Noli Me Tangere, which has only screened a handful of times since its 1971 debut. [the 4.5-hr cut, titled Out 1: Spectre, gets a little more play.] Save the date(s), because it’s coming to the AMMI’s Rivette retrospective in November.

An Elusive All-Day Film and the Bug-Eyed Few Who Have Seen It [nyt]

Smithsonian Sells Archive To CBS For $6 Million

Why is that not the headline for any of the stories about the Smithsonian’s exclusive TV programming deal with Showtime?

Smithsonian officials signed a 30-year contract with CBS Corporation’s Showtime division giving them rights of first refusal to any “commercial” films produced using the Smithsonian’s collection, archives or experts in any more than an “incidental” way.

Look back 30 years and ask yourself what changes have been wrought in the cable TV market, the Internet, and film production. How many of them did you foresee? How many of them did you write into your contracts in 1976?

Then ask yourself what changes might occur in the next 30 years. Look what’s happened to the distribution of independent and user-created video with YouTube and Google Video in just the last year, for example, the same year it took for Showtime and Smithsonian to negotiate their secret deal. And since the Smithsonian sale came to light in March, AOL has also announced its own video competitor to YouTube.

From Robert Rodriguez’ home studio operation and Soderbergh’s HD Bubble to Jonathan Caouette’s DV/iMovie Tarnation to Rocketboom to liveblogging to Matt Haughey’s Star Wars Kid remake, we’re in the early days of an independently-created video content revolution. How many tens of thousands of potential documentaries, features, and shorts and who-knows-what-kinds of programs could be created in the next three years, never mind the next thirty, if the national patrimony held by the Smithsonian were made available in the way that, say, the BBC is planning to do? They’re opening their entire archive for remixing and reuse by the people who paid for it–the citizens and residents of the UK.

Instead, the Smithsonian has locked its holdings up for thirty years with a single company–CBS/Showtime–and for what? The right to make six programs per year outside the agreement, a 10% stake in the Smithsonian On Demand service, and guaranteed payments of $500,000 a year, plus some unknown percentage of future profits or revenues.

At even the most conservative calculations, the present value of those $500,000 payments is around $7.9 million. At a more typical discount rate (the historical risk-free rate of 8%), Showtime sews up 30 years of exclusive use of the Smithsonian’s resources for a freakin’ $6 million.

So not only did Smithsonian executives sell out America’s patrimony to a single, giant media corporation, they sold it for practically nothing.

Is there no other way for the Smithsonian to bring in $500k/year? Did they look at any other options at all? Did they consider at all the benefits and costs beyond guaranteed annual payments? For screenplays it helps develop that get turned into actual films, The Sundance Institute asks for a donation of a fraction of a percent of the film’s production budget, and 1% net profit participation.

What would be result if the Smithsonian charged a 0.5% fee for each program it cooperates with? It signed an average of 180 media contracts/year between 2000 and 2005. With an average budget of even $250,000, that’s already $225,000/year. Now imagine thousands or tens of thousands of filmmakers using the Institute’s collections to make tiny-budget–but commercially viable–content in the near future we’re already beginning to imagine.

The Smithsonian executives’ dogged insistence that only a very few filmmakers are affected demonstrates an inexcusable lack of some combination of vision, integrity, or sense of responsibility, and it shortchanges both the Institute and the country to the exclusive benefit of CBS. From the standpoint of what we got–and more importantly, of what we lost–we, the American people, have been thoroughly ripped off.

Smithsonian Hands Over TV Contract [wapo]

The West Side Is Among Us Again

Whit Stillman not only lives, he writes in the Guardain about what the heck he’s been working on all this time. Some adaptation that didn’t work out, a script about Jamaican gospel churches…

As I’ve gone from identifying with the protagonists of Metropolitan to the aging yuppie at the bar at JG Melon’s in Metropolitan, I have to say, I’m a little put off by Mr. Stillman’s apparently laconic–or wary, maybe–approach to filmmaking.

But that’s probably because I seem to be doing the same thing, bouncing back and forth in stolen moments between pipe dream projects and adaptations. I just haven’t got three features under my belt.

Confessions of a serial drifter [guardian via greencine]