I’m repeatedly fascinated by how Robert Gober brings the same extraordinary production detail to his editions as to his sculptures. Sometimes the goal seems to be uncanny, handmade verisimilitude, as when he makes a receipt or a movie ticket stub. But Untitled (2011) is something else.

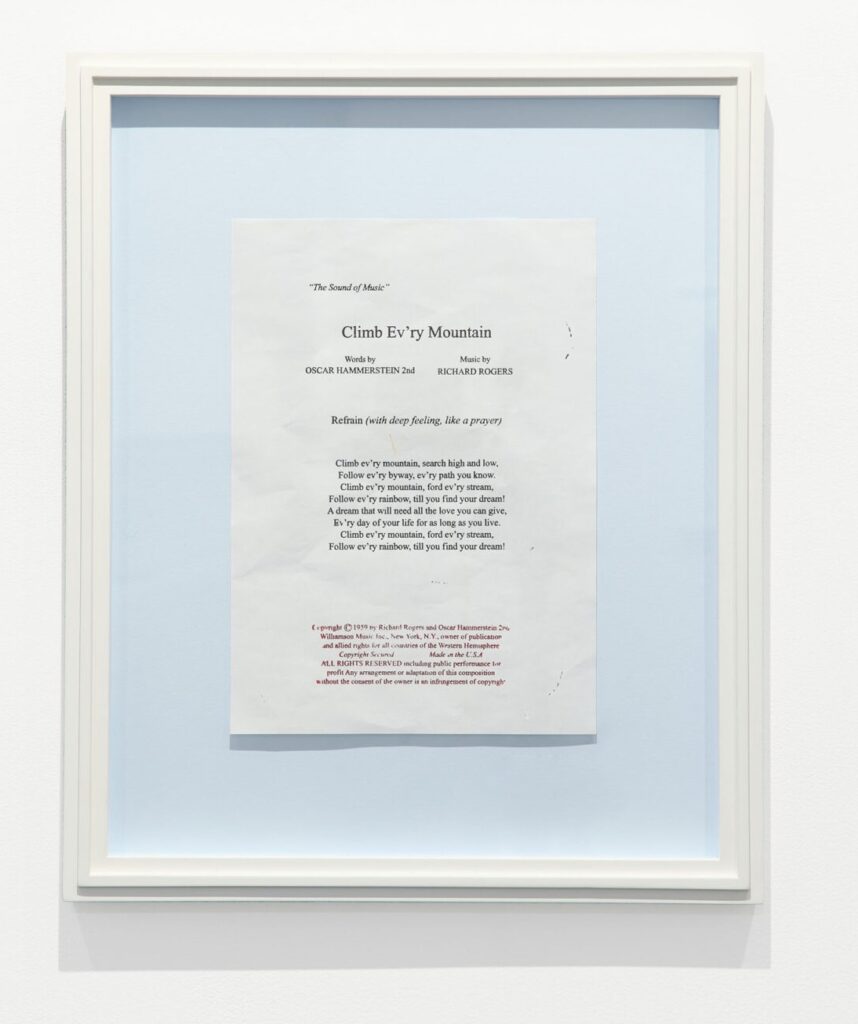

Untitled is a two-color potato print of the lyrics to the Rogers & Hammerstein song, “Climb Ev’ry Mountain,” from The Sound of Music, along with the copyright notice. It is mounted in an artist’s frame, so it is really an object, not just a print, but the primary point is, it is a potato print.

An example of the edition of 15 is on view in Boston at Krakow Witkin Gallery’s One Wall One Work series. The gallery also has published an extensive account of the production process, which could not be more different from the time you or I made a potato print at camp with a pen knife and tempera paint.

It involves freeze drying potato slabs, and infusing them with something solid enough to engrave the text with a CNC router. In the first step, it perhaps resembles Gober’s presentation of a bag of donuts. The latter engraving process feels like the kind of technical challenge a master printer would love. Then there’s preparing the paper, and bringing it all together.

Indeed, the whole process here, and its innocent childhood implications, seems to be as prominent as the subject and content itself. As the gallery puts it,

A potato print is a rudimentary printmaking technique often used by young students, using half of a potato rather than metal or stone plate. Gober has taken this makeshift single-use medium and refined it to such an extreme that he could create a highly detailed, illusionistic image repeatedly (in an edition of 15). The themes of ‘how what can work for children can also be used by adults’ and that ‘there can be creative solutions to seemingly insurmountable situations’ feel directly related to “The Sound of Music,” nostalgia in general, and the present moment.

[next morning update: the details of the production history and technique seem to originate in an uncredited document published in May 2024, as part of the Brooklyn auction of AP 1/5 from the edition. Thanks to @bbhilley.bsky.social for finding it.

It now makes me wonder where it came from, and where it circulated. It contains much detail of the behind-the-scenes between the conservators, engravers, printers, and studio; was it provided to buyers by the gallery? Do the buyers of Gober’s work receive a packet of information to the inevitable question, “How’d he even do that?” Does there exist among Gober collectors a layer of intricate knowledge even beyond that gleaned by living with his work?

And I wasn’t going to get into it last night because of the sheer fascination of the potato, but the gallery’s mention of the careful reproduction of the copyright notice and the artist’s receipt of authorization from the Rogers & Hammerstein folks also appears in this production document. The exactness with which Gober, et al. observe the lyrics’ IP—and then document it—brings the whole cultural system of music publishing and performing into this work that was, again, printed with potato.]

One Wall, One Work: Robert Gober is on view through Dec. 7, 2024 [krakowwitkingallery via greg.org hero matt]