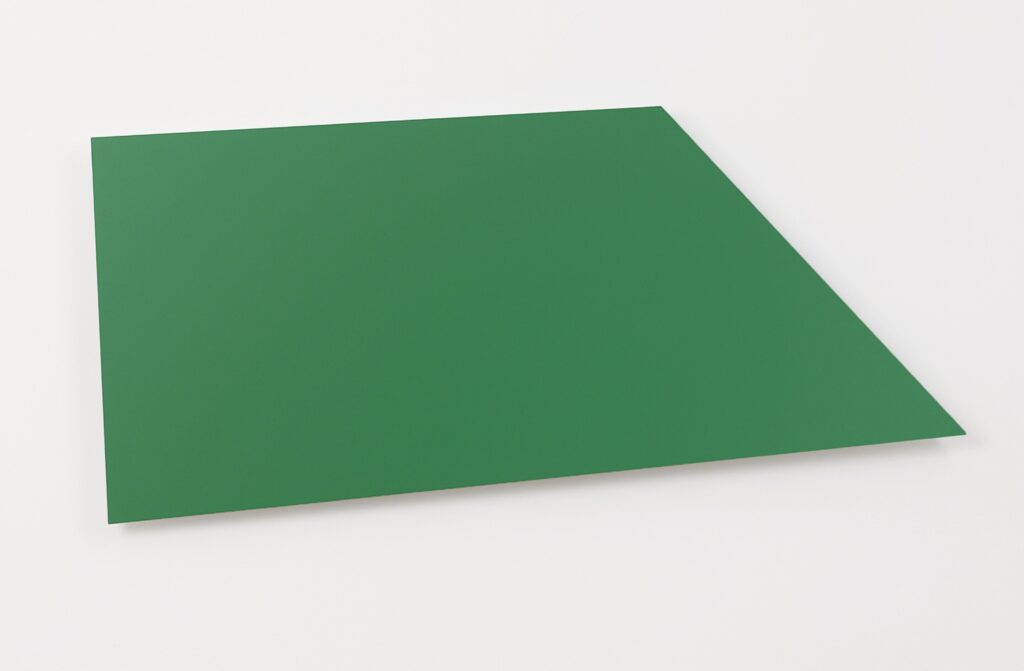

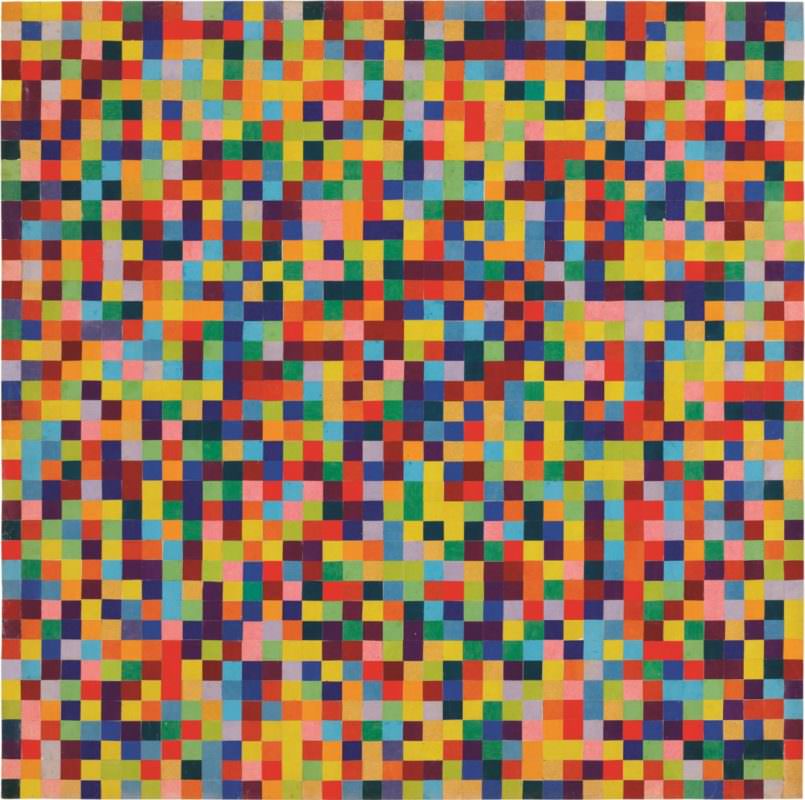

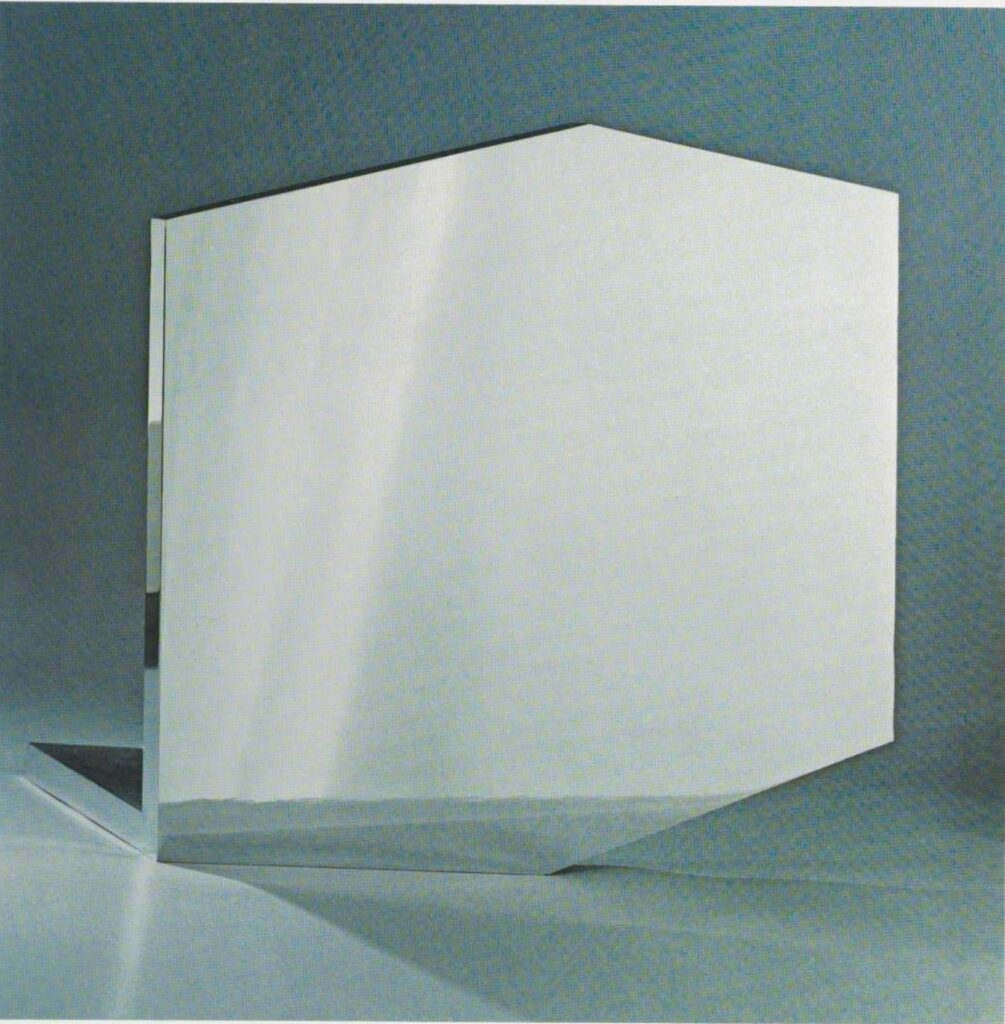

Looking up something else in the catalogue for Technics and Creativity II, MoMA’s 1971 exhibition about Gemini G.E.L.’s process, I was stopped in my scrolling tracks by this excellent full page photo of Ellsworth Kelly’s Mirrored Concorde.

It absolutely looked like the future. And in a sense, it was: Mirrored Concorde was an edition in progress, just entering production with an undetermined edition size. Which, hold that thought. But the image itself, with its dramatic lighting, refractions, and straightforward mirrored materiality really hit.

That’s not quite how the work has turned out, alas, though it’s still a beautiful thing. It seems like there were only 16 made by 1972, when the work was officially published: an edition of 12, plus two copies each for Kelly and Gemini.

Unlike the free sculpture above, the examples out in the world have various bases and pedestals that make me wonder if it’s a little top-heavy. Christie’s incorporated the base into the 50 7/8 in. height, but while they broke out the metal pieces, neither Brooke Alexander nor Matthew Marks included the base in the depth.

The truncated rectangular shape is one Kelly used as early as the 1950s; this one feels like it could be the hexagonal outline of a 3-D cube diagram. The mirror finish is very unusual in his work. After cutting, the 1-inch steel plate elements were ground, lapped, and polished on the sides and edges, then nickel- and chrome-plated. Which, I guess that’s ok, but could they not have just kept polishing? [Asked the guy who didn’t make one of these things, much less sixteen.]

Maybe Kelly did wonder the same thing, because the similarly scaled wall relief edition he made in 1985-86 Untitled (Gemini EK86-2128), was only polished, not plated. [It was only polished on the face and edges, though, and the steel is only 3/8-inch thick. There was also an edition with a sandblasted finish.] The shield shape was in heavy rotation; it showed up in paintings in the late 70s, and then a Cor-Ten steel relief in 1984, which TV producer Douglas Cramer owned.

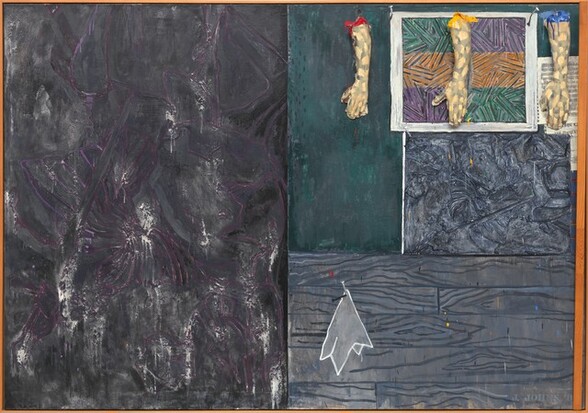

So maybe I like the top pic so much because it actually feels like a mirror-finished object. Every other image of Mirrored Concorde makes it look like Featureless Matte Finish Concorde. Seeing James Mathews’ installation photo of the MoMA show, I can confirm.

Even on its wonky pedestal, behind its stanchion, and against its painted accent wall, Mirrored Concorde manages to look like a portal to another dimension. Because what it actually reflects is the world in front of it: the museum’s sculpture garden through the Philip Johnson addition’s windows, with one of Claes Oldenburg’s Ice Bag sculptures peeking its motorized head up. Let this be one more argument in support of photographing mirrors to look like mirrors.