a gift of the artist to the nation, in the collection of the National Gallery of Art

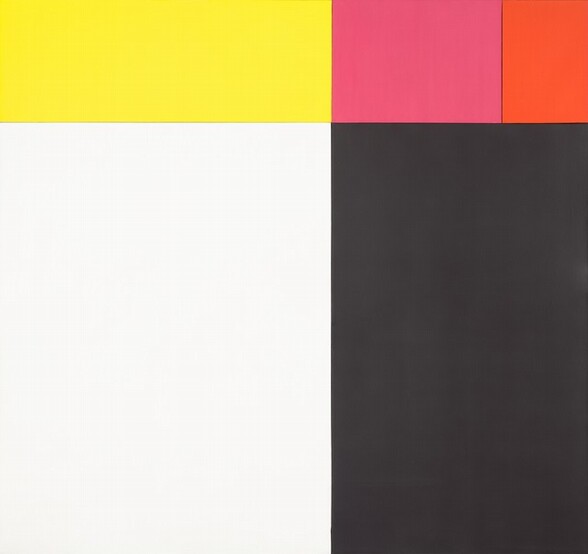

One of the great rewards of the Ellsworth Kelly @ 100 retrospective at Glenstone is seeing this foundational, early multi-panel work, Tiger, from 1953, which is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

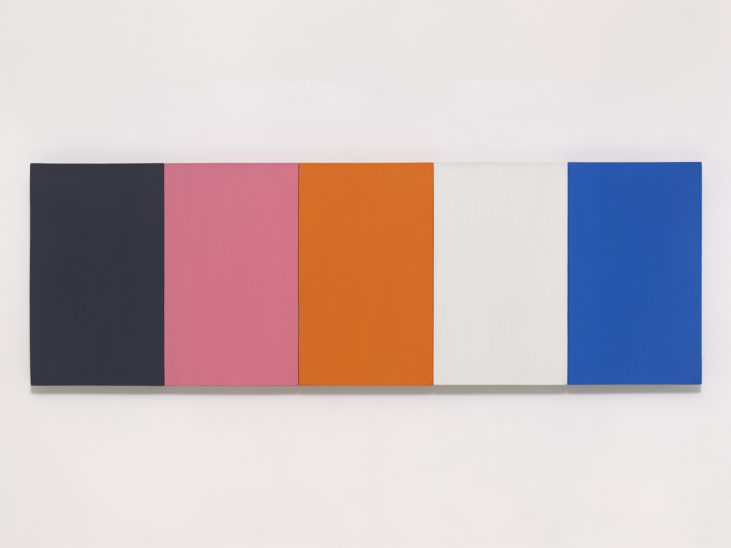

Kelly worked out the colors and dimensions of the five monochrome panels in Sanary, a seaside village in France he visited in 1952. It’s one of the largest of the very few paintings he actually made in France and brought home with him to New York in 1954. The work he developed in Sanary has been on my mind for years; it’s some of his formative work that would inform his whole career.

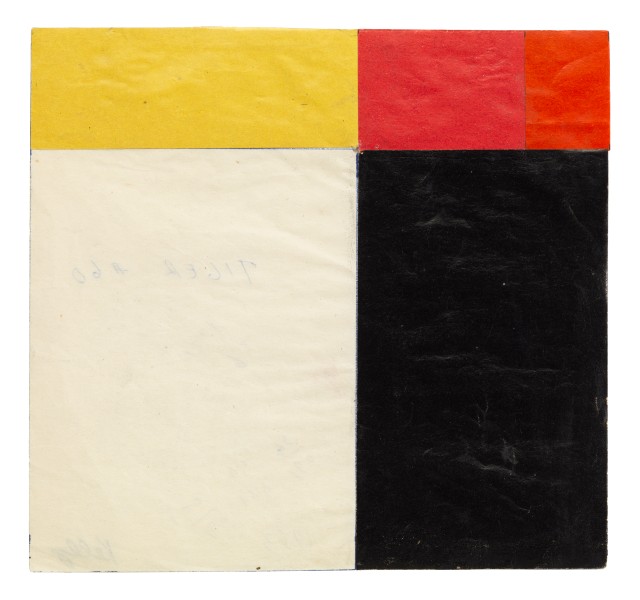

The NGA’s text, written by curator Molly Donovan, cites Yve Alain Bois’ research that Kelly began with found colors, a set of paper stickers used in French kindergartens known as papier gommette. The colors are very similar to another multipanel work from the same moment, Painting for a White Wall, 1952, which is now in Glenstone’s collection. As Yve-Alain Bois discussed here when his CR Vol. 1 came out, Tiger was instrumental to the beginning of Kelly’s official exploration of color behavior; it was where he set out to understand “the strange orange/pink” that had occurred in the found colors of Painting for a White Wall.

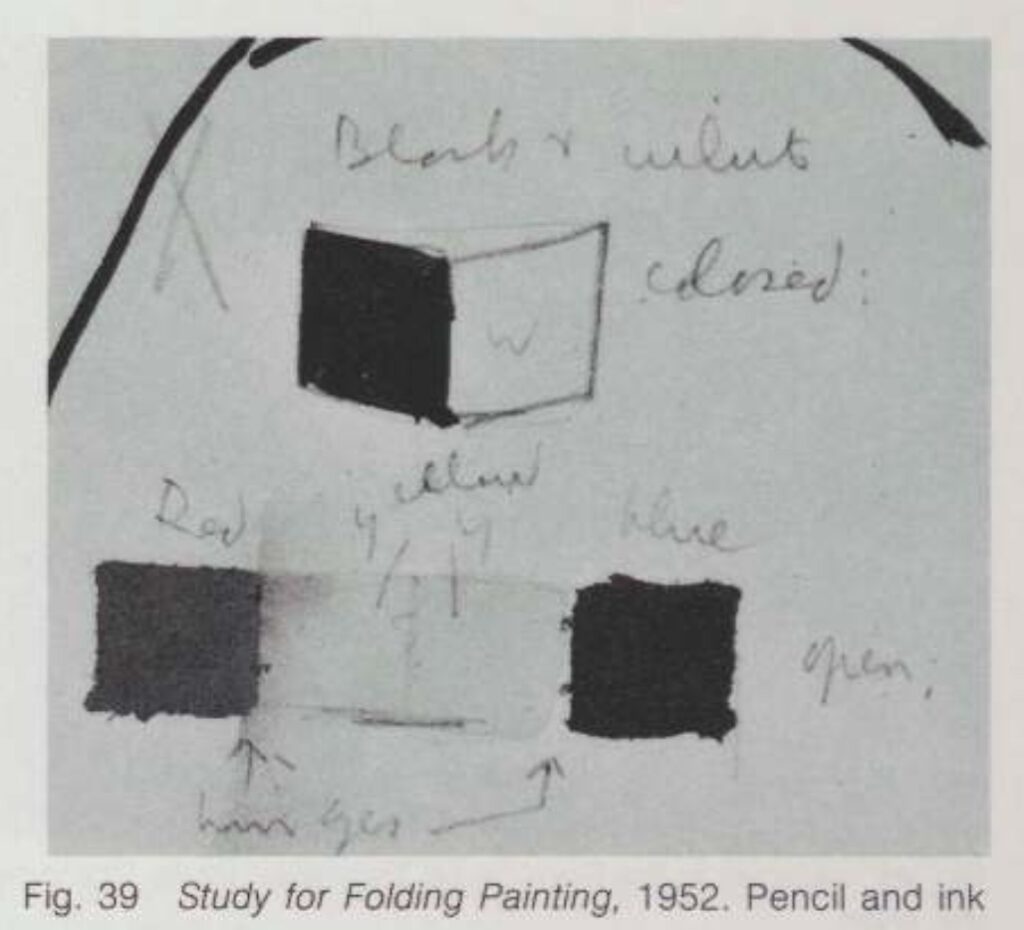

Anyway, the relationships of the various panels are intuited, not mathematical. Kelly worked them out in sketches and collages, like the one Matthew Marks brought to Basel in 2017.

What I didn’t know until seeing the painting in person and reading up on it, is Kelly’s interest in the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald. In the 1973 catalogue for Kelly’s MoMA retrospective E.C. Goossen mentions Kelly’s Sanary-era sketchbooks include drawings of the altarpiece’s hinged construction alongside drawings of various compositions of windows and shutters, and even studies for a hinged painting. The connection to Kelly’s most important Paris painting—also in the Glenstone show—the multipanel construction repeating the window of the Musée d’Art Moderne, is obvious.

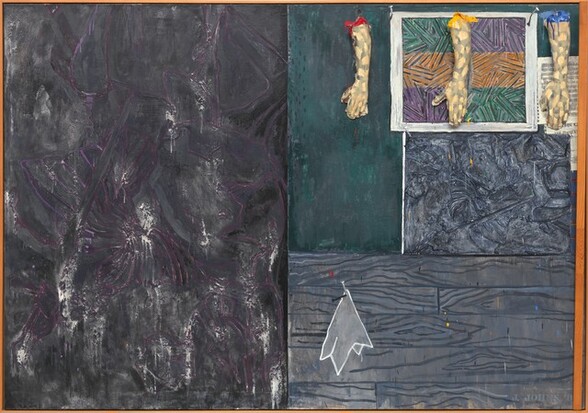

What most intrigues me, though, is the possible connection to Jasper Johns. In 1987 Jill Johnston did an exhaustive and revelatory analysis of Johns’ incorporation of fragments and details of the Isenheim Altarpiece into his paintings in the 1980s. One of the first is Perilous Night, from 1982, a work that is also at the National Gallery.

Actually, now that I put it up there, the composition of Johns’ painting feels very resonant with that of Kelly’s panels in Tiger. Johns did tell Johnston he got a book about the Isenheim Altarpiece from a friend. Didn’t say who, though. From Short Circuit to Flag to In Memory of My Feelings, hinged and multipanel paintings were on the minds of young artists in downtown Manhattan in 1954. I wonder what we could learn from a Kelly/Johns show. I’m sure Tiger would be a fascinating starting point.

[Next day update: On an impulse I checked for reservations at Glenstone last night, and there was space available this morning, so I went, and it was hot and glorious. I listened to most of an aquatic horticulturist lecture pondside, which was fascinating. The pond in the center of the Pavilions building is as thoughtful as the rest of the landscape, which really never disappoints. Even Split Rocker looked good. Not landscape per se, but you know.

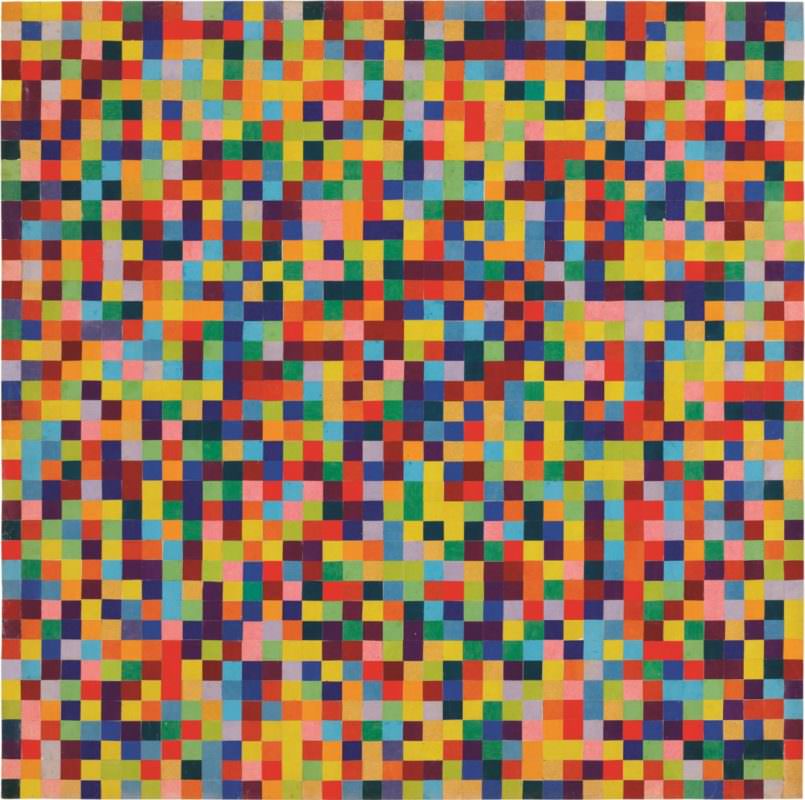

There were some new pieces in the Charles Ray pavilion, always a marvel. And a couple of beautiful Kelly works on paper, including the dazzling, large collage above, from 1951, in the spot where Tiger was hanging. So I guess they rotate things. It was a low-key flex that they had such an amazing work on hand and didn’t just jump to include it in the show, but chose to let the loans tell the fuller story of Kelly’s practice. Truly a dynamic place amidst all the contemplative stillness.]