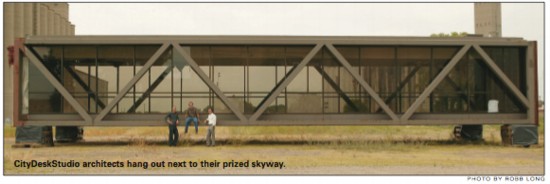

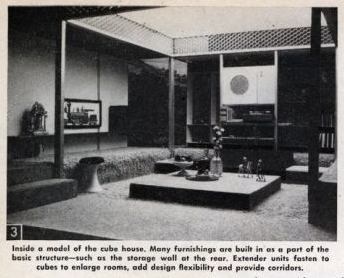

If the Eames House was not available, I decided it would be fine to live in a gas station felt like an appealingly modernist alternative. I’ve kept a list, to which I also added a decommissioned Minneapolis skyway, a temporary MoMA fire escape, and a reconstituted world’s fair pavilion or two. I would also add a greenhouse. There used to be a most excellent abandoned greenhouse on the roof of a building which you could see from the Roosevelt Island tram. Perhaps, I thought, Lacaton & Vassal could help me persuade the family, who, it turns out, really do not want to live in any of these repurposed industrial structures.

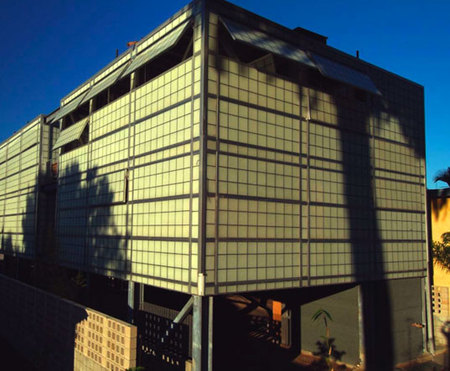

Now there is another. [shoutout Geraldine for the heads up] From 2011 until 2013 Stockholm architect and organizer Viktor Marx worked with Cyklopen, an autonomy-minded community organization, to rebuild their gathering space, which had been firebombed by neo-nazis. The result, Cyklopen Kulturhas is as spectacular as it is utilitarian.

The 2-storey, 459 sq. m. structure was optimized for safety, for flexibility, and for the self-sufficient group’s donated labor. A laminated lumber core was raised by hand, Amish barn-style, and ringed with upscaled scaffolding, on which the greenhouse-style tinted polycarbonate skin was hung. The upper floor, aka The Box, is enclosed and climate controlled; the open ground floor and mezzanine space are not. Let’s say it’s responsive to the climate.

There is room to spend a little more than almost no money to bougie up the place without, I think, losing the adapted reuse credibility. Solar panels. Radiant floors. Some Kieran Timberlake-style Bosch Rexroth extruded aluminum beams. [It’s fascinating that even with some formalist similarities, KT’s Cellophane House was optimized for the diametric opposite factors to Cyklopen: high end components were pre-constructed offsite, then shipped and craned into place in midtown in a few days, with stupendous logistical complexity and expense.]

Ultimately, I find what is holding me back from living the gas station/greenhouse/shed dream–besides the family buy-in, obviously–is the suburbanity, the single family house-ness of it all. I am a city person. We are city people, and a site where I could reasonably build a Swedish anarchist Bifröst greenhouse is nowhere near a subway–at least since MoMA built that Jean Nouvel supertower on the vacant lot next door. So I will add Cyklopen to the moodboard in my heart, and wish the original a bright and impactful future.

They accept donations, btw. [cyklopen.se, thanks to @geraldine@post.lurk.org for the heads up.]