Apex Art just announced that Courtenay Finn and Gary Fogelson were selected for this year’s open curating slots. Finn’s proposal uses a work by Bruce Nauman as a jumping off point for a show about “the role of reading in artistic practice.” Fogelson’s will tell the incredible-sounding history of alternative, arts, and experimental filmmaking shown in the 1970s on Boston’s WBBI TV. Congratulations to both of them, and get cracking, time’s a wastin’!

I’d had an idea for a show percolating for a while, so I submitted it. As I re-read it now, it’s fascinating how much of it is stuff I’ve blogged about over the last couple of years. In a real sense, the blogging process was central to the development and coalescence of the show’s ideas, if not for the actual proposal, which I wrote up and submitted anonymously, as Apex Art requires.

It tied for 45th place out of 320 entries. 86th percentile, which is alright, I guess, in a B-show kind of way.

Anyway, it was inspired, as the title suggests, by Enzo Mari. It challenges the common conception of aura by applying Mari’s autoprogettazione reproduction strategy to instructions-based art practice.

And because it also includes references to the great gatherer of Unrealized Projects, Hans Ulrich Obrist, I thought I’d go ahead and share my proposal here. If you’re one of the 40 international, anonymous judges who rated it less than 4/5, I do hope you’ll drop me a line and tell me what might have improved it for you.

Many thanks to those folks who gave me feedback and art historical suggestions on the idea as I was putting it together, too. I don’t want to sound namedroppy–until we polish this bad boy up and put on this jargon-laden, Stingelpainting party somewhere else, then I’ll be thanking you often and loudly, I’m sure.

Proposta per un’auraprogettazione

A project for making easy-to-assemble furniture using rough boards and nails. An elementary technique to teach anyone to look at present production with a critical eye. (Anyone, apart from factories and traders, can use these designs to make them by themselves. The author hopes the idea will last into the future and asks those who build the furniture, and in particular, variations of it, to send photos to his studio…) – Enzo Mari, Proposta per un’autoprogettazione, Duchamp Center, Bologna, April 1974

Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura is commonly understood as a quality that distinguishes an original art object from its mechanical reproduction. Recent alternative readings [Samuel Weber, 1996], particularly of cinema–Benjamin’s archetypal medium of modernity–consider aura as something not lost in (re)production, but instead contingent upon it. Aura is generated through contextualized reception via dispersed, multiple ‘originals,’ as literary or musical aura is transmitted via books and scores.

When coupled with Benjamin’s functional reconfiguration of the distinction between author and reader [“through a highly specialized work process…the reader gains access to authorship”], production of an auratic artwork at a [spatial/temporal] remove from the artist herself becomes feasible. The instruction performs such a distancing function.

From Moholy-Nagy through Lewitt, artists have used instructions and plans to challenge the privileging of gesture and authorship. The emergence of Conceptual art saw the concurrent normalization of instruction-based practice and the “dematerialization of the art object” [Lucy Lippard, 1973].

Lippard’s own seminal exhibition 557,087 (Seattle, 1969) was executed remotely using artists’ instructions, which comprised the show’s catalogue. Similarly, Do It (1993-) an ongoing exhibition/archive by Hans-Ulrich Obrist, solicits, executes and disseminates instructions from contemporary artists. [“With Do It in hand, you will be able to make a work of (someone else’s) art yourself.”]

Despite their critique of object/market complicity, instructions are regularly sublimated by capitalist constructs [i.e., editioning, certificates of authenticity] that reassert control and facilitate commodification.

Authorization thus emerges as a crucial and highly contested point of inflection/exchange for instruction-based work. Only five of 168+ instructions in Do It generate objects. One, a Felix Gonzalez-Torres candy pour (1994), was problematized when the artist’s catalogue raisonné [Cantje, 1997] reclassified it as “non-work” and reconfigured fabrication authority only for Do It‘s curators, not its audience.

A more conceptually robust corollary is art that applies a model exemplified by the Italian designer Enzo Mari, whose 1974 exhibition/catalogue, Proposta per un’autoprogettazione, (Proposal for a self-project) included not just blueprints for making 16 pieces of furniture, but explicit authorization to do so.

Mari’s autoprogettazione structure synthesizes Benjamin’s potential for multiple, auratic originals with the critical empowerment of readers-qua-authors, consumers-qua-producers, viewers-qua-artists.

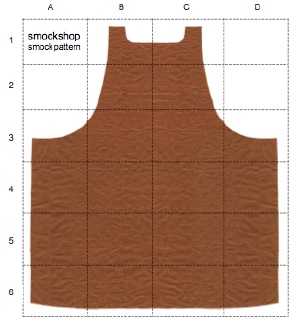

Auraprogettazione will be the first ever survey of this distinctive, exceptional genre: auratic objects, fabricated by whomever, in accordance with artists’ published instructions and authorization. Preliminary research has identified consonant works–painting, sculpture, photography, assemblage, clothing–by at least eleven artists: Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Stephen Kaltenbach, Lia Maisonnave/Ciclo de Arte Experimental, Yoko Ono, Tobias Rehberger, Rudolf Stingel, Joep van Lieshout, Franz West, Zhuang Da, and Andrea Zittel.

Alongside the ‘originals’ exhibition, the gallery may be activated as a site of open, facilitated art production, or as an aggregator/repository of audience-made originals. Additional artists may be solicited to create new, permissioned, instruction-based work. And as with Mari’s original, Auraprogettazione‘s publications in print and online will propagate instructions for the exhibited works.