There’s some interesting background info as well, but the big news [sic] today in piecing together the history of Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit is that Finch College is off the hook–and Holland Cotter is right after all.

In his 1976 Rauschenberg catalogue, Walter Hopps appeared to say that Jasper Johns’ flag painting was stolen in 1967, while the combine was on exhibit at Finch College Museum on the Upper East Side.

But the day after I wrote that, Holland Cotter described the Johns flag as having been stolen in 1965. Stolen and replaced.

I still don’t know about replaced, but in Michael Crichton’s 1977 Johns catalogue for the Whitney, he says the flag was stolen while Short Circuit was in Castelli’s warehouse “before June 8, 1965.”

And thanks to Christel Hollevoet’s 1996 Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews, we can probably put a “stolen after” date of at least December 1962 on it, too.

That’s when Johns wrote a letter to the editors of Portable Gallery Bulletin, which had criticized Rauschenberg for not releasing a photo of Short Circuit to them. [I found this via MoMA’s Johns bibliography, btw.]

After noting that Rauschenberg had given Johns’ career a “helping hand” by including a flag painting in his combine years before Johns’ first show, editor Albert Vanderburg had complained that “due to the personal insistence of Robert Rauschenberg,” the photo of Short Circuit, whose “historical value” is “indisputable,” had been suppressed as part of “a cover-up of politlcal maneuvering.”

From Johns’ reply:

Dear Sir:

I’ve always supposed that artists were allowed to paint however-whatever they pleased and to do whatever they please with their work–to or not to give, sell, lend, allow reproduction, rework, destroy, repair, or exhibit it…Rauschenberg’s decision was part of a solution of differences of opinion between him and me over commercial and aesthetic values relating to that work. The painting itself has been publicly exhibited at least twice and, I believe, slides of it have been used in connection with public lectures…

And so in 1962, months after his and Rauschenberg’s acrimonious separation, Johns asserts complete authority to do with his painting as he chooses. And that he was also involved in not reproducing it–or not handing a slide over to Portable Gallery, which was kind of a slide bank/library. Johns’ acknowledgment that there were “differences of opinion” over the “commercial and aesthetic values” of “that work” And that “a solution” was reached is the most I’ve been extensive, specific explanation of the work(s) so far. What were the other parts of the solution and who held what opinion, it’s impossible to say, but the facts on the ground–Johns’ exclusion of Short Circuit from his Flag narrative, Rauschenberg’s retention of the work in his own collection until his death–probably give some clues.

But it’s clear that as a major early work comprised of major work by both artists, Short Circuit became a specific locus of contention when they split. And while it’s a bit beyond my pay grade to say what its actual meaning or importance is, I think Short Circuit‘s centrality to both artists’ work and dialogue, and to their relationship, fully justifies the slightly Errol Morris-y obsession around here.

The theft–or really, the removal–of the flag painting is still a mystery, and it complicates any assumptions about the artists’ “solution.” If Crichton’s date–presumably taken from a document in the Castelli archives, which now happen to be undergoing cataloging and processing at the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art–is correct, it narrows down the list of possible flag-takers from “whoever might have seen the Finch show,” to “whoever had access to Castelli’s warehouse between 1963 [?] and 1965.” None of this shed any more light on Calvin Tomkins’ story about a dealer bringing the stolen flag to Castelli for authentication. Or on where the flag might be now.

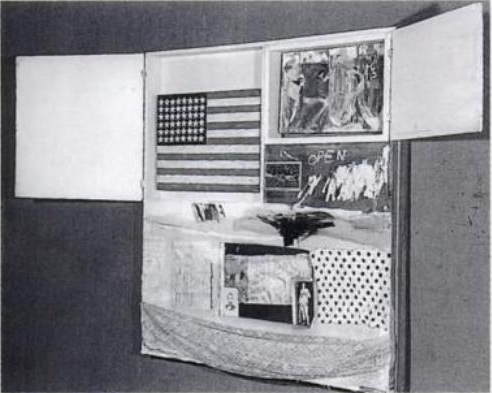

But back to Short Circuit and that photo [which Crichton said came from Castelli’s 1965 Johns file, not his Rauschenberg file.] I think it’s the one I keep posting, the black & white, oblique shot [with Johns’ original flag which, incidentally, measures 13 1/4 x 17 1/4 inches]. 1965 may be the “stolen by” date, but when was Sturtevant’s replacement introduced? In 1976, Hopps seemed to say 1967, for the Finch College show. But the Finch show was either represented solely as a Johns flag, and/or the combine doors were nailed shut. And in 1976, Hopps still had to use the original photo.

So to recap, the flag was “stolen” by 1965, was never reported as such. Castelli saw it again afterward, in the custody of a dealer, but seemingly did nothing about it. Short Circuit was exhibited and reported as containing a Johns flag in 1967-8, but the doors were nailed shut. And the earliest mention so far of Sturtevant’s replica is 1976, next to Rauschenberg’s comment about repainting it himself as therapy.

In other words, several more pieces of information, but still no closer to figuring out what actually happened.