From the jump, the experience of encountering a Sturtevant is different from almost all other artworks. The moment of recognition, of loading up your assumptions and expectations of an artist’s work, of anticipating a certain kind of engagement is the same, until the instant it isn’t. Sturtevant’s work triggers a recognition, and then it thwarts it. When you realize a work is by Sturtevant, you consider how close she has gotten to the artist you thought it was by; then you start marking differences. You may also start to reflect on your upended expectations, and to question the systems that produced them.

And by you, I mean me. And the Sturtevant work that has been confounding me for months is Gonzalez-Torres Untitled (Blue Placebo). The 2004 sculpture is a repetition of “Untitled” (Blue Placebo), a 1991 pour of blue cellophane-wrapped candy. The Sturtevant was acquired by the Whitney Museum in 2016, and it went on view for the first time this summer in “Inheritance,” an expansive collection exhibition about legacy and lineage curated by Rujeko Hockley.

As far as I can tell, Sturtevant only made one candy pour. It was shown at least twice in the artist’s lifetime, and this is the second time since her death. How does it work? What does it do? How does a museum handle it? Is there a certificate?

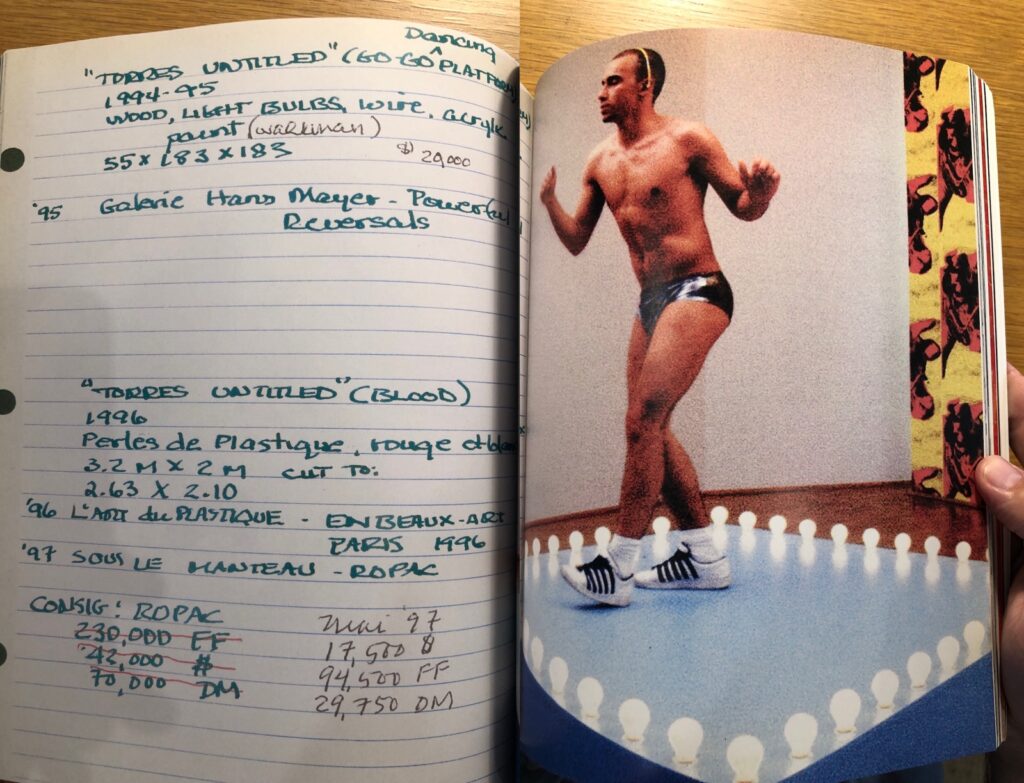

Sturtevant made her Blue Placebo for her 2004 exhibition at the MMK in Frankfurt. It was one of three repetitions of Gonzalez-Torres included in the show. [The others were a 12-strand light string and a go-go dancing platform. She also, amazingly, included Gonzalez Torres’ actual Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform), creating a situation of dueling—or duetting?—go-go dancers, which Bruce Hainley elaborated upon in his Artforum review. It echos the time in 1996 when she showed her bead curtain in Paris while Felix’s bead curtain was on view at the Musée d’Art Moderne. Which, stay tuned.]

“Untitled” (Blue Placebo) was the first candy pour to sell at auction, in 2001, which boosted its visibility. The Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo bought it for $666,000. But it was also exhibited at Jennifer Flay in Paris in 1997, which may account for its visibility to Sturtevant.

“If you use a source-work as a catalyst, you throw out representation. And once you do that, you can start talking about the understructure.” Sturtevant told Peter Halley in 2005. What is the representation of a Gonzalez-Torres work, and what is the understructure? Is it the parameters of “ideal weight” and candy type? Is it the particular form the work took when it became a catalyst? Is it the concept of viewers engaging with the work by taking a piece of the candy? The metaphor of illness, death and renewal? How far down into Gonzalez-Torres’ structure does Sturtevant reach?

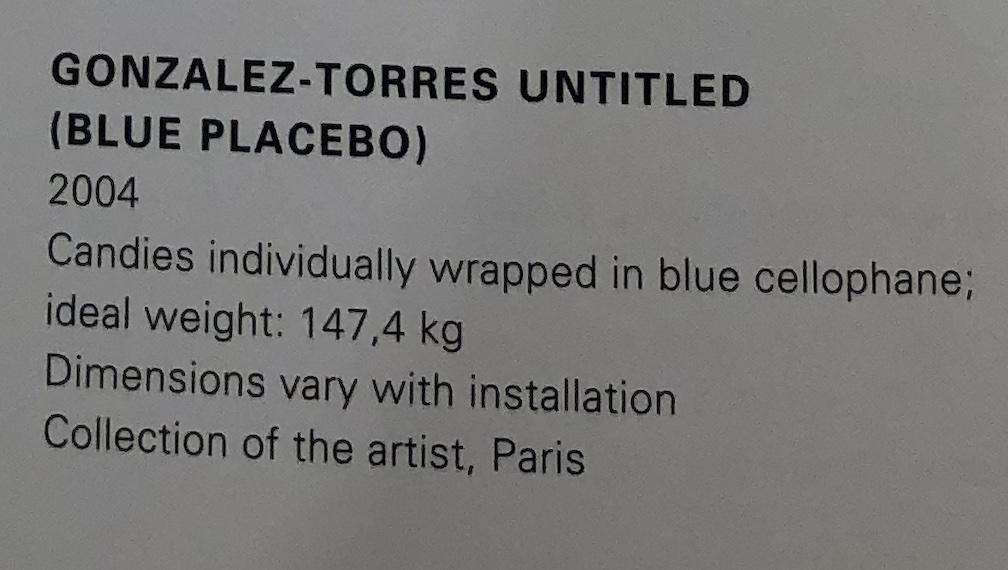

In 1997 and 2001, at least, the “ideal weight” was 147.4 kg (325 lbs), and the form was royal blue candies in a rectangular field against a wall. These are the specs Sturtevant repeated in Frankfurt. They were also repeated when her gallerist Thaddeus Ropac showed the work at Frieze in 2008, and at Art Basel Unlimited in 2015 [above], which is where and when the Whitney got it, as a gift from Eleanor Heyman Propp.

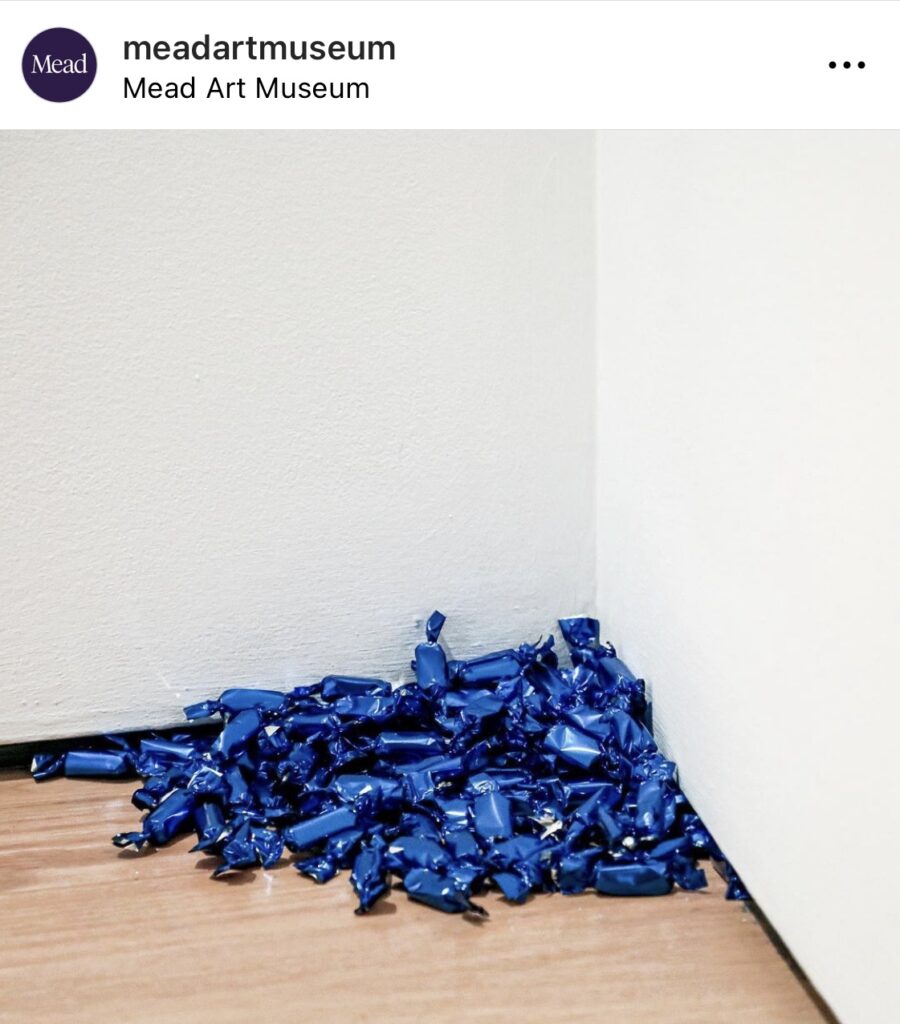

Since its acquisition in 2001, Felix’s original has dropped some weight somehow, and is now 130kg (286 lbs). And the colors of blue have varied as often as the shape of the pile. In Spring 2023, art historian Niko Vicario taught a seminar at Amherst that involved multiple incarnations of Gonzalez Torres’ “Untitled” (Blue Placebo) at the Mead Museum. Sturtevant’s work is decoupled from those changes. The Whitney’s label explains that Sturtevant “instruct[ed] the exhibitor to create a long rectangle of blue-wrapped hard candies on the floor. As in the original, viewers are invited to take a candy, and the pile is replenished periodically.”

A spokesperson for the museum confirmed that the piece does have “formalized installation instructions,” though they and the artist’s gallery did not refer to the work having a certificate. When Sturtevant made her Gonzalez-Torres pieces, Felix’s certificates were not as widely discussed or considered as they have become. It was only in 2006, in her contribution to the texts Julia Ault edited for the FGT Foundation, that Miwon Kwon [pdf] said the impact of the “‘Private’ aspect of FGT’s work—by which I do not mean aspects of the artist’s biography but the behind-the-commercial-scenes contracts of transaction that regulate the work’s conditions of ownership, exchange, and public presentation” was more “radical” and “significant” than that of the artworks’ form and content.

Kwon quotes a certificate for another 1991 candy pile, “Untitled” (Loverboy): “The nature of this work is that its uniqueness is defined by its ownership, verified by a certificate of authenticity/ownership.”

Though Sturtevant seemingly did not focus on Felix’s certificates specifically, she was quite interested in the understructures of ownership, exchange, and public presentation. In the 2004 MMK catalogue, Pompidou curator Bernard Blistène wrote, “In defiance of ‘copy-right’ or the artistic ownership, Sturtevant’s project resembles in some way and ahead of its time, jurisprudence…The first fruits of ‘copy-left,’ Sturtevant’s art agitates ahead of the others for the abolition of the principle of ownership.”

This dichotomous view of ownership deserves much more attention, even if it is complicated a bit by Sturtevant’s work now being owned by a museum. Similarly, her repetition freezes, or preserves, one instantiation of Gonzalez-Torres’ candy pile as it was conceptualized at a moment in time, FGT’s work shifts and propagates in multiple forms, all while the Foundation, owners, and curators maintain the immutable parts of its understructure.

The Whitney’s wall label also says, “In echoing Gonzalez-Torres’ expression of grief, Sturtevant’s work serves as an homage both to the original action and to the artist himself, who died of AIDS-related causes in 1996.” Which I guess makes sense in a gallery devoted to the theme of Homage, but which I cannot, in one million years, imagine Sturtevant saying. If anything, her Blue Placebo erases any trace of homage, elegy, and biographical interpretation from the work. It’s closer to the 2001 Christie’s catalogue essay, which omitted any reference to the artist’s or his partner’s sexuality, AIDS, or death: “Like many of Gonzalez-Torres’ other works, “Untitled” (Blue Placebo) refers to the existence of an illness, yet within that reference there lies a glimmer of hope, as the placebo might offer the cure.”

Along with the ownership thing, this is the core of my fascination with this work in this place. Are Gonzalez-Torres’ forms really considered to possess intrinsic meaning? When graphic designers are making stack exhibitions in Venice, and Darren Bader is publishing books as a pile of fortune cookies, I think the answer has to be no. Shouldn’t Sturtevant’s repetition strip away all the poetic, symbolic, and metaphorical scaffolding that transformed a shiny, monochrome cellophane carpet into a work of memorial art? Are we really not left with free candy and questions? I don’t think the museum is quite there yet.