Imagine an internet retail revolution that not only created online shopping, but that brought digital shopping into the physical world. The mp3 store. The gaming store. The stock footage store.

The stock footage store.

Imagine a bustling day in 2009 or ’10 at the iStockVideo store in Paris, in the old BHV, the department store where Duchamp bought his readymades. Under the high ceiling a long table arrayed with great horned owl footage. A chic but cantankerous Sturtevant and a cheery, slightly sheepish Spike Jonze both rummaging through the tablets, realizing each other’s presence when the reach for the same clip. They look up, Jonze smiles, says, “Pardon” in his downtown French, and pulls back his hand. He casually peruses his way to another clip.

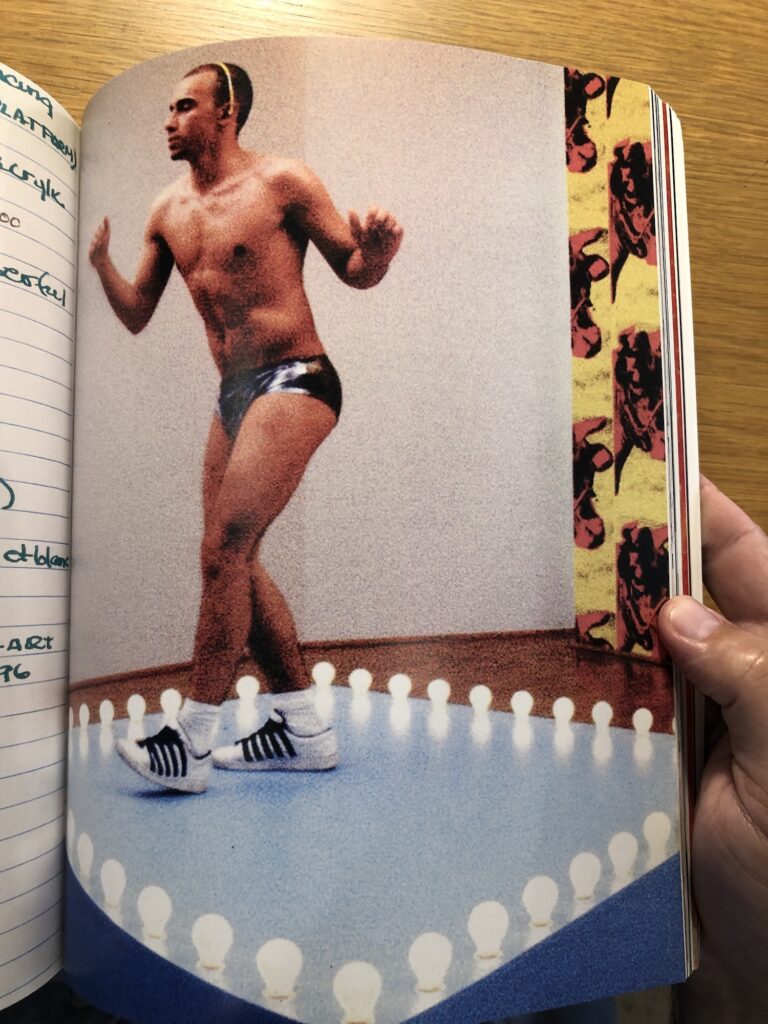

Imagine in that world, as in ours, Sturtevant opens a show at the Serpentine in 2013. Spike Jonze’s Her, 2013, was released in France on March 19, 2014, and Sturtevant died on May 7. Imagine this 89 year old Deleuzian, in what would be the last few weeks of her life, going to the cinema to see the movie about the guy in love with his bot. In that world, as in ours, she just opened a show at the Serpentine with a video wall of owl footage. She sees this scene of Joaquin Phoenix on the sidewalk.

Does she then remember that fleeting encounter, years earlier, at the owl clip shop? Is the question I’d rather consider than the one this world has presented me when tumblr’s algorithm presented this gif to me because it thought I “looked interested.”