The irony, of course, is that if Walter Robinson actually had the balls to fire Charlie Finch for this kind of crap, the skeevy old skank would probably just turn around and start a blog.

Charlie Finch Goes Too Far [MAN, with a list of drumbeating links]

Previously: ACFWLF: [I think this stands for “Artists Charlie Finch Would Like To F***”]

Category: art

Well Duh, Because It’s Gus Van Sant.

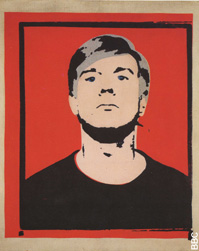

Finally, someone’s saying something about the inconsistencies, conflicts and caprices of the Warhol Authentication Board, which is wreaking quiet, opaque havoc on the market for Andy Warhol’s artworks. The BBC is showing a documentary on the Board tonight on BBC1 called “Andy Warhol: Denied”.

The above self-portrait, from 1964-65, for example, which Warhol gave as payment to Richard Eckstract, an important collaborator in Warhol’s films, was subsequently declared inauthentic.

Is this a real Warhol? [telegraph.co.uk via boingboing]

What If Sprawl Is The Real Entropy?

Maybe we have the whole Smithsonian entropy thing wrong.

In 2002, Artforum’s Nico Israel whined with condescension about the homogenous strip mall & fast food landscape he had to endure on his road trip from one perfectly isolated Earthwork [Spiral Jetty] to another [Double Negative].

Then, as the Jetty has re-emerged year after year, visitor traffic has increased dramatically, along with press coverage and local awareness and appreciation.

Road signs to the Jetty appear in the middle of what was once unmarked desert scrub.

Tour buses idle where once only high-clearance 4WD’s were advised to go. The Dia Center takes ownership [?] of the Jetty.

And Smithson’s widow, fresh on the heels of fabricating a piece that didn’t exist during the artist’s lifetime, mentions offhandedly that she doesn’t see how adding rocks and regrading ramps would conflict with her husband’s idea of entropy.

And now, the industrial detritus that has long defined the Jetty’s site for visitors–and, to some extent at least, for the artist himself, who chose Rozel Point as much for the abandoned oil derricks as for the water’s reddish-pink tint–has been cleaned up and hauled away, deemed “an eyesore” by the State [as if anyone had bothered to look there until a couple of years ago].

Should we care? Conventional art world wisdom holds that Smithson’s entropy dictated a hands-off approach to his work. Que sera sera, dust to dust. Nature will take its inexorable course; stopping, fighting, or reversing this [d]evolution through restoration, maintenance, or re-creation is doing a disservice to Smithson’s ideas and his legacy.

“The Spiral Doily,” picked up in Utah on

my last trip to the Jetty

But in his seminal Artforum essay of 1966, “Entropy and the New Monuments,” the examples of entropy Smithson cited weren’t ivy-covered ruins and rubble, but New Jersey, Philip Johnson and the “cold glass boxes” of Park Avenue, and suburban sprawl. “The slurbs, urban sprawl, and the infinite number, of housing developments of the postwar boom have contributed to the architecture of entropy.”

Just this week, Reuters reported on a land use study that shows Suburban Sprawl may be an irrestistable force in the US. When he sited Spiral Jetty in BF Utah, was Smithson building against New Jerseyification, or just ahead of it? Is it possible–or is it just convenient acquiescence to suggest–that roped-off “Nature”-driven degradation is not, in fact, entropy, but Romanticism? Maybe letting “civilization” have its paving, scrubbing, sprucing up, licensing, Acoustiguiding, Ritz Carlton Jettyway Weekend Packaging way with the Jetty isn’t closer to the end game Smithson envisioned?

Entropy and the New Monuments [robertsmithson.com]

Suburban sprawl an irresistible force in US [reuters]

Artnet Dorks Out Over Dorkbot

Wow, Artnet associate editor Ben Davis got just what he wanted for Christmas: the chance to write at length about art and technology. He covers the video game-inspired show at Pace Wildenstein in Chelsea last month [generally, eh] and better-reviewed shows like Bit Edition‘s multi-artist animation collaboration in Brooklyn with vertexList, and a Dewan Brothers show at Pierogi [they’re like the Harry Partch of synthesizers, very DIY.] But he saves most of the love for Dorkbot, aka Gearhacking: The Gathering, that monthly rendezvous of people doing wack stuff with gear.

Technical Knock-Outs [artnet]

Cleanup Crew: 1, Entropy: 0 At The Spiral Jetty

From The Salt Lake Tribune, 1/21/06:

Spiral Jetty cleanup: Utah officials last month removed several tons of junk from Rozel Point, the area along the Great Salt Lake’s north shore that is home to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.

“Anyone who has made the trip to see the famous Spiral Jetty . . . has passed through the area and certainly noted that it was an eyesore,” says Joel Frandsen, director of the state Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands, which supervised the cleanup along with the state Division of Oil, Gas and Mining.

Workers removed 18 loads of junk and plugged more than a dozen abandoned oil wells.

I spoke to someone at Forestry for some more detail. Included in that list of eyesores are the burned out trailer, that weird amphibious tank thing, the abandoned cars, basically most of the industrial detritus that fed into visitors’ sense of Smithsonian entropy. [Todd discusses this and has pictures of the now-gone junk on From The Floor.]

And about those oil wells, it turns out the oil is quite viscous, kind of tar-like, and it pools very slowly over the years. Some might say that for Smithson, that’s not a bug; it’s a feature. Well it’s moot now.

The project took a couple of weeks and supposedly focused only on sovereign land: state-owned shoreline, which is determined by elevation [i.e., the land, below 4,201′ I think, which is about four feet higher than the Jetty itself. Depending on the terrain, a 4′ change in elevation can take you quite a ways inland, although I can’t see it going all the way up to the trailer…hmm.]

There was also talk of negotiating an easement for parking, so that visitors won’t have to park on the road or trespass when they park beyond the “end of road” sign.

I didn’t get the sense that the Dia Center was involved in the project in any way, but we’ll see. I have some queries into them at the moment. The deadline for bids for a concession to operate a capuccino-and-smoothie cart during the peak Jetty months of June-October will begin March 15. OK, I made that last one up. I hope.

SLTrib Visual Arts [sltrib.com, thanks to Monty for the heads up]

Previous greg.org-on-Jetty action

Elmgreen & Dragset Blitz London [sic]

My boys Elmgreen & Dragset are opening their show, The Welfare State, at the Serpentine tomorrow, and there’s a conference related to the show at the Goethe Institute on Friday, and there’s a fat catalogue on every day, whenever you like. [oops, actually, it’s not out in the US until March.]

Kultureflash has images from the show’s first incarnation at Kunsthall Bergen, Norway.

Meanwhile, here’s a photo they sent me from just before their Prada Marfa project opened last fall. That there’s Boyd on the left.

First You Get The Money, Then You Get The Power

As the year winds to an end, I think I can officially say it: the art world is whack. It’s all about the Benjamins, and I don’t mean Walter.

I was going to post a diatribe, but instead, I’ll just point out what I’ve already said in print: the small comparison I made between the ravenous fixation on Richard Prince’s appropriations and the parodic, poll-driven works of Komar & Melamid; my calling into question the credibility of a system [i.e., price] that persists in systematically discounting the influence, importance, and value of half the culture; a pair of artists’ self-serving embrace of that same system to overinflate the importance of their work; and the apparently unstoppable influence of the market on the conceptual underpinnings of an artist’s work after he’s gone.

Jerry Saltz hits on a lot of it in his great, biting end-of-year essay in the Voice this week. [I’m glad someone else will call BS on that hilariously embarassing Wizard of Oz photospread in Vogue last month. The idea that someone with a straight [sic] face asked the famously closeted Jasper Johns to be the Cowardly Lion? If I didn’t know how deadly serious the Vogue people took it, I’d say it was the awesomest slam ever of the whole artist-as-vapid-celebrity schtick since Francesco Vezzoli.]

Here’s hoping that in 2006, somehow the bubble will pop, the winds will change, and not too many of my friends’ livelihoods will suffer too much as a result; because I’m looking forward to seeing the art that comes out of it.

Free MoMA

I have 20 16 14 10 8 4 free passes to MoMA that expire on 12/31/05. If you’d like a couple, please drop me a line, and I’ll mail them out to you today.

[update: I ended up with 4 passes left, but now I’m out of town and won’t be back before they expire. Sorry. The Target Corporation invites you to Free Friday Nights at MoMA, though… Merry Christmas, &c.]

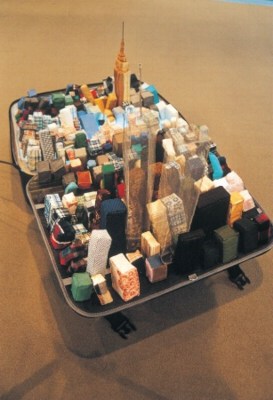

Yin Xiuzhen’s Portable Cities

Beijing-based artist Yin Xiuzhen’s Portable Cities series are models of cities inside suitcases, made using the old clothes that city’s residents. In her practice, she explores issues of globalization and homogenization, but also memory and transience.

In a way, her work reminds me of the nomadic Japanese artist Tadashi Kawamata, who constructs temporary structures, favelas, and whirlwind-like vortices out of scrap wood and junk he collects around the city. While they exist, they put into play issues of development and destruction and (im)permanence.

Anyway, Yin’s sewn suitcase version of New York City from 2003 includes a shimmering, ephemeral version of the World Trade Center made out of what looks like mesh or organza or something. It’s really quite nice.

via Regine, who has some links to Yin’s work at the Sydney Biennial last year. Yin was also in “How Latitudes Become Art” in 2003 at the Walker Art Center. Her NYC gallery is Ethan Cohen Fine Arts.

Zaha’s Cojones, Neto’s Ovaries

I’ve been waiting for anyone else to say it, but Zaha Hadid must have some serious cojones to show up in Miami–his own home [away from home] town!–sporting a gigantic Ernesto Neto fallopian tube sculpture. I mean, Neto’s Venice installation is like two blocks away in the Margulies Warehouse. Don’t even get me started on Anish Kapoor’s Turbine Hall. Seriously, woman, WTF?

From The Mixed Up Files Of Ms. Nikke Finke

Mike Ovitz can fight his own battles–although he’s been nothing but genial to me, I don’t doubt he can be a pretty scrappy guy. But Nikki Finke’s LA Weekly article on Hollywood-style dealmaking supposedly poisoning the art world is such a raw-yet-feeble Ovitz takedown attempt, I can’t see why it even exists.

And that’s even before you notice that the story’s so old, a veritable reportorial time capsule. The most recent anecdotes are from the early 1990’s. Julian Schnabel–get this!–has a movie about Basquiat. Up-and-coming dealer Mary Boone has revitalized SoHo’s gallery scene. One interviewee, Leo Castelli, actually died in 1999. Rather than even update the story or provide any la plus ca change context, it reads like Finke handed in an old floppy disk she found while cleaning out a storage unit in the Valley, and her editors published whatever killed story or chapter of an abandoned book happened to be on it. What’s next? Finke’s incisive report whether Waterworld‘s production turmoil will threaten Kevin Costner’s status as Hollywood’s sexiest leading man?

And that’s even before you notice that the story’s so old, a veritable reportorial time capsule. The most recent anecdotes are from the early 1990’s. Julian Schnabel–get this!–has a movie about Basquiat. Up-and-coming dealer Mary Boone has revitalized SoHo’s gallery scene. One interviewee, Leo Castelli, actually died in 1999. Rather than even update the story or provide any la plus ca change context, it reads like Finke handed in an old floppy disk she found while cleaning out a storage unit in the Valley, and her editors published whatever killed story or chapter of an abandoned book happened to be on it. What’s next? Finke’s incisive report whether Waterworld‘s production turmoil will threaten Kevin Costner’s status as Hollywood’s sexiest leading man?

Lest you think the cluelessness is confined to alt-freebies on the West Coast, Artforum linked to Finke’s story with a headline and a blurb so inaccurate [“For Hollywood Moguls, Collecting Is Increasingly De Rigueur”] it’s obvious they didn’t even read the piece.

Blame Ovitz: When Art Started Imitating Hollywood [laweekly via artforum]

So A Gate And A Floating Island Walk Into A Bar

There are some posters, and some beer, and the gas for the motorboat had to cost a pretty penny, but that’s about it. Compared to the expensive (and purportedly expensive) public art it skewered, The Gate that chased Robert Smithson’s Floating Island up the East River a couple of months ago cost nothing. Now the Gate and the boat, and a documentary about the project will go on exhibit 11/18 at Redhead, the gallery of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council.

The artists–who still remain unnamed–intended their project to ask and answer the questions, “Is public art still possible? Can a cheap stunt pack a punch? Does art make enough room to laugh at itself? Yes. When money steps aside and lets the work do the talking.”

A Cheap Publicity Stunt, 11/18-12/22, at Redhead [lmcc.net via greg.org reader chandra]

Previously: Water, Gate. The Gates Bill

The Sound Of One Hand Bidding

What with the hazmat crew required to neutralize the thousands of gallons of formaldehyde and the efforts to stabilize the rotting, soaked corpse, moving Damien Hirst’s shark costs an estimated $100,000.

Meanwhile, Mark Fletcher and Tobias Meyer ended up donating a John Bock sculpture to the Carnegie rather than keep replacing the fresh melons in it.

[Maybe they should have become Buddhists. When I was a missionary in Japan, old ladies were always offering us the fruit offerings–pyramids of oranges and melons, usually–from their butsudans, the black lacquer, gilt-edged, in-home shrines where they prayed to their departed family members.]

“These works become like devotional objects. It’s like caring for your altarpiece,” said Amy Cappellazzo, Tobias Meyer’s Christie’s counterpart.

Ephemeral Art, Eternal Vigilance [nyt]

Previously: how contemporary art is like a renaissance tapestry

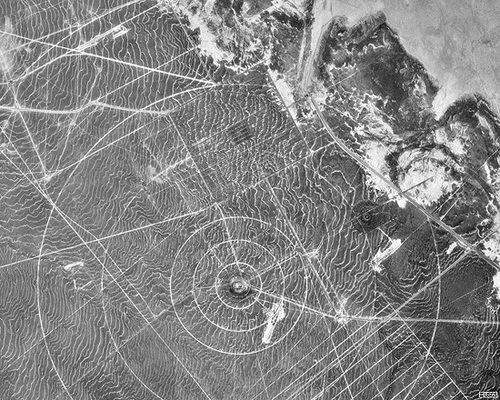

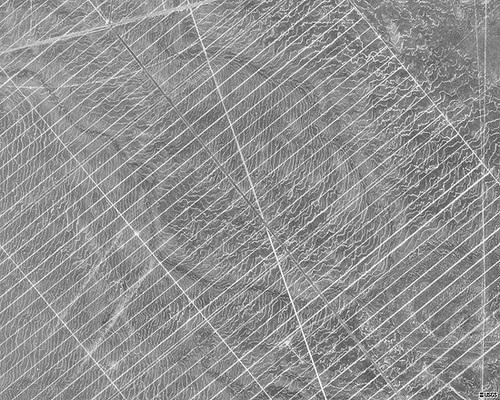

Digging Dugway

Whoa. The Dugway Proving Ground is in Skull Valley, an hour and a half west of Salt Lake City. It’s where the US Army tests chemical and biological weapons and defense systems. It’s the site of an incineration program for the US’s stockpiles of bio/chem weapons. And it’s probably the greatest piece of Earth Art since the Nazca Lines.

The DoD’s alterations of the landscape–seen here in Terraserver photographs–rival the Spiral Jetty, Double Negative, Roden Crater, even, in both aesthetic power and content. Flash forward a few hundred years and ask yourself, which desert markmaking will have the most to say about the mid-20th century?

Dugway’s been dealt out of the Earth Art discussion because it’s a) functional, and b) institutional, not individual, but those seem like quaint technicalities. What if the only reason they’re not considered art–or considered alongside art, at least–is that no one’s really had access to them?

Dugway Proving Ground [pruned, via tropolism]

previously: earth art via satellite

John Powers-a-Day at Virgil de Voldere Gallery

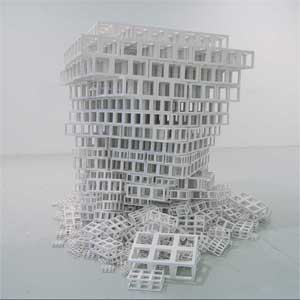

When I first met John Powers five+ years ago, he was like a Tibetan monk with a pile of sand. Only instead of sand, he had thousands of 1-inch woodblocks, which he transformed into a huge, impossibly intricate, mandala-like sculpture that sprawled across the floor of Exit Art’s gallery. Every day throughout the exhibit, he scooted around on a little skateboard chair, replicating and altering dense patterns of blocks as he went. The work wasn’t “finished” when the show ended, and he swept the whole thing away, but that, I think was part of the point.

Now, in his latest show at Virgil de Voldere Gallery in the Chelsea Arts Building, Powers is reconfiguring hundreds? thousands? of white, Sol Lewitt-like grid modules into a new sculpture every day. The gallery’s website has pictures of the ones you’ve missed, but you can also stop by until Oct. 9th to watch new pieces come together.

John Powers at Virgil de Voldere through Sun., Oct. 9 [virgilgallery.com]