Wait, The Empire was the US and the Rebellion was the North Vietnamese, but Lucas only put them in space after Hollywood suits wouldn’t let him make Apocalypse Now? And the grunge was a simultaneous obeisance and refutation of the antiseptic future of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, which like half Lucas’s crew had worked on? What next, John Powers, that Leia was actually his sister?

Duh. Also, the Deathstar is Judd, the Millennium Falcon is Smithson–and Bob Morris is Obiwan Freakin’ Kenobi, Jedi Freaking Master.

I’ve watched and discussed and swooned for months as Powers shaped his analysis, and I’m still floored and fascinated by it. I can’t think of any other example of scholarship that approaches this formative film with such seriousness and wit. I can’t wait for it to be turned into an a capella ditty and/or toaster.

Star Wars: A New Heap, by John Powers [triple canopy]

Category: making movies

Thomas Kinkade: Filmmaker Of Light

Interesting. Vanity Fair published the 16-point memo painter Thomas Kinkade distributed to the crew before they began shooting Thomas Kinkade’s Christmas Cottage, a film telling Kinkade’s own creation myth, how he became an artist to save his mom’s house from foreclosure.

The memo is pretty facile, all sunsets and shadows, and there are multiple instructions to the crew to, when in doubt, add more Barry Lyndon. Also, . And hidden references to reward what, “[i]n the realm of fine art we refer to…as ‘second reading, third reading, etc.'”

…References to my children (from youngest to oldest as follows): Evie, Winsor, Chandler and Merritt. References to my anniversary date, the number 52, the number 82, and the number 5282 (for fun, notice how many times this appears in my major published works). Hidden N’s throughout — preferably thirty N’s, commemorating one N for each year since the events happened.

Hmm, sounds like fun.

Vanity Fair has a softly illuminated fish in a careworn barrel, and they still can’t shoot it. The set is snobby and misinformed at best. The movie is not “based on one of his paintings,” but on Kinkade’s own youth. His paintings are probably all based on his fantasy/memories of his youth, then, but still. This single sentence is shot through with lazy inaccuracies:

The art world has never exactly embraced Kinkade, though in the last 16 years his company and its partners have reportedly made more than $4 billion selling his signature renderings of idyllic settings, which employ diffuse light sources, aggressive pastels, and a domineering religious worldview.

The art world has never embraced Kinkade. His once-publicly traded company’s topline revenues are easily researchable, and there’s no mention of its implosion and the collapse of his over-merchandised, over-franchised house of cards. And on and on.

He’s been reduced to a licensing hack, but there has to be a better analysis–or even a more thoughtful takedown–to be made about the willfully escapist nostalgia that drives people to make–and consume–art like Kinkade’s.

As if the caliber of the actors weren’t enough–from Marcia Gay Harden and Peter O’Toole, to Ed Asner and Chris “Cabin Boy” Elliott–to warrant some attention, there’s the film’s timely-yet-impossibly fanciful story itself. I mean which aspect is sounds more fairy tale-ish to you? That making art is the obvious, instant path to financial security, that a small, white town would be brought together by a random mural painting, or that the unimaginable crisis they rally to solve is an impending foreclosure?

Though Kinkade’s memo is shot through with references to creating mood and emotion, there is essentially no mention of character, performance, motivation, even the story. It’s like all that evocation happens regardless of the actors, or what happens in these candlelit scenes. But his paintings never have actual people in them, just hints of people. Kinkade’s memo’s unstated goal seems to be the faithful re-creation of the experience of viewing one of his paintings. Whatever joy or nausea that entails depends on the viewer.

Thomas Kinkade’s 16 Guidelines for Making Stuff Suck [vanityfair.com via kottke]

Hmm, title change, implausible date: Thomas Kinkade’s Home for Christmas (2008) (V) [imdb]

Films, Fax Murals & More: Stan VanDerBeek At Guild & Greyshkul

I first encountered filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek’s work in Aspen Magazine. His 1964 collaboration with Robert Morris, Site, combined dance/performance, art, and film. Performers create a physical, 3-D approximation of camera wipes and reveals using large black and white panels. Though Morris and VanDerBeek made it years before, it reminds me of early video art work from WGBH that explored the functions and visual properties of the new technology.

Throughout his career, VanDerBeek was an “advocate of the application of a utopian fusion of art and technology.” [That’s from his E.A.I bio on Ubu, btw.] Which would be interesting enough on its own. But until I get down there to see the actual show, what I find most fascinating about Guild & Greyshkul’s current survey of VanDerBeek’s varied output is the intricacies of how his family began dealing with it after he passed away.

Two of G&G’s artist-owners are VanDerBeek’s children, and the process they went through–part biographical, part familial, part art historical, part archive/conservational–is just awesome. Sara VanDerBeek’s discussion with Brian Sholis is at Artforum.com.

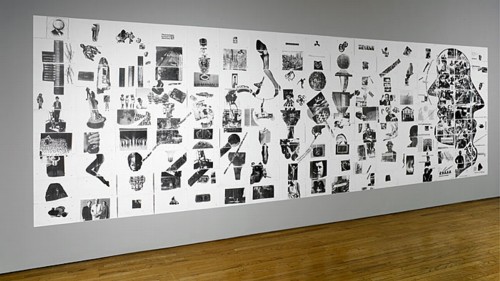

The image above is Panels for the Walls of the World, a 153-panel “fax mural” which VanDerBeek sent from MIT to various places around the country in 1970. Phase I, above, was transmitted to the Walker Art Center. There were four “phases” of Panels, and it’s possible that a significant percentage of all the fax toner in the country in 1970 was exhausted printing out VanDerBeek’s murals.

Stan VanDerBeek runs through Oct. 18 at Guild & Greyshkul; Navigate from this crazy page, too [guildgreyshkul]

500 Words | Stan VanDerBeek by Sara VanDerBeek [artforum]

Films of Stan VanDerBeek [ubu]

Madness, Madness

On the occasion of a Film Forum series of his work, Terrence Rafferty has an interesting, if brief and kind of depressing think about David Lean’s method in the NY Times.

Maybe the series can wrest Lean away from the clutches of the cinematic cliche crowd that always puts Lawrence of Arabia in their award show montages. He’s kind of like the Dalai Lama; a no doubt great god who attracts the most annoying sort of sycophantic groupies. [Or is that Tarantino?]

Bonus: block out Katherine Hepburn’s schtick and just treat Summertime as a fantastic documentary of 1950’s Venice. Also, the movie was blurbed by the film critic of the Daily Worker. !

Related: David Ehrenstein’s relook at Lean in Artforum makes me feel a little guilty.

Waiting For Godot Times, Thursdays At 8, 9 Central

Daniel Birnbaum in Artforum, discussing “Beckett/Nauman,” a Spring 2000 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Wien

The organizers of “Beckett/Nauman,” Kunsthalle Wien curator Christine Hoffmann and art historian Michael Glasmeier, aren’t really out to prove anything, but their juxtaposition of works by the two artists provides ample ground for comparison and analysis of thematic affinities. This is not a major Nauman show in the ordinary sense, even if a number of important pieces–A Cast of the Space under My Chair, 1965-68, lots of videos, and two “corridors,” one shown for the very first time–are effectively installed. It’s not a major Beckett show either, for there’s no such thing. This is something else entirely: a gray inventory of impossible connections or an archive of discontinuities. It’s a genealogical space rather than a show. Full of detailed information–manuscripts, drawings, notebooks, and sketches–the exhibition piqued curiosity and made the viewer attentive. I liked it a lot.

Emphasis added on the part I liked a lot. But wait, there’s more…

Birnbaum makes the argument that Beckett and Nauman aren’t actually intergenerational inspirational source/recipient, but contemporaries. Did you know Beckett adapted a play for the BBC in 1977, and produced several teleplays and what must be considered video art pieces for TV as late as the Eighties? Here’s a clip of Quad I & II, a wordless experiment in rhythm and rulemaking created for the German broadcaster Süddeutscher Rundfunk. Come to think of it, yeah. When was Mummenschantz again? Oh, wait, I thought I was totally kidding.

Film, meanwhile was Beckett’s first and only film screenplay. 40 pages, comprising notes and diagrams around a “fairly baffling when not downright inscrutable six-page outline,” Becket wrote it in 1963 and shot it in New York in 1964. Film dealt with E and O [for Eye and Object, apparently] and “the question of ‘perceivedness,’ the angle of immunity, and the essential principle that esse est percipi: to be is to be perceived.” For 20 wordless minutes, a camera follows an aged Buster Keaton as he tries to avoid being seen.

Is Film online? Of course it is, thanks to UbuWeb. [There’s also a clip on YouTube.] Ubu also has director Alan Schneider’s account of making the film, where I got the quotes in the previous paragraph.

[thanks reference library]

The Post-Apocalyptic Open-Pit Mines Are Alive With The Sound Of Music

Alright, so last night I made some wisecrack about a scene from Kevin Costner’s 1997 film The Postman, where a mutant general pacifies his slave army by showing The Sound of Music on a floating theater on a lake at the bottom of an open-pit mine, might be a mashup of a couple of Robert Smithson’s unrealized installations. Little did I know.

I rewatched the scene just now, and it’s positively Smithsonian. I remembered some things incorrectly. [I hadn’t seen the movie since Christmas Night, 1997, when I had a private screening–on what turned out to be opening night, whoops–at a desolate multiplex in Salt Lake City.] Like I’d forgotten how spectacular it is, really well-crafted and poetic, even, for what amounts to a single note in the film [hats off to cinematographer Stephen Windon and the wonderfully named production designer Ida Random].

And the slave soldier army isn’t floating around, watching; they’re perched on the tiers of the open pit mine; I got that mixed up with the harborside cinema scene in Cinema Paradiso: in The Postman, only the projectionist is floating, in his little booth that looks like the offspring of Smithson’s Floating Island and his Partially Collapsed Shed.

I’d also forgotten completely about Dolph Lundgren. As the scene opens, and the ersatz movie theater is revealed, the screen first fills with explosions, the opening credits of Dolph Lundgren’s Universal Soldier. But–unexpectedly!–the crowd of soldiers revolts and starts raining rocks down on the poor projectionist in his floating booth. He quickly changes the movie [beat] to The Sound of Music, and the mob is subdued.

In his Cinema Cavern, Smithson wanted to show only one film, Film On The Making [of] Cinema Cavern. But after a long day of killing in the mines, the “ultimate film-goers” in The Postman reject their own “making of” film, preferring instead the escapist fantasy of Julie Andrews, the singing, Nazi-thwarting nun.

Anyway, there are a bunch of tasty screencaps on flickr and after the jump. Enjoy.

previously: “truly ‘underground’ cinema”

Continue reading “The Post-Apocalyptic Open-Pit Mines Are Alive With The Sound Of Music”

“Truly ‘Underground’ Cinema”

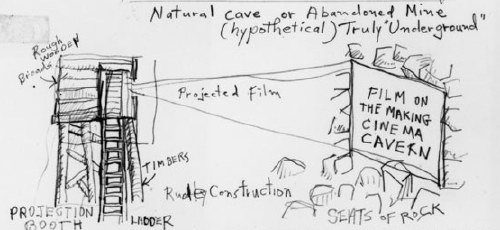

I loved Cabinet before I wrote for them, and I love them after. In the latest issue, #30 The Underground, Colby Chamberlain looks at an awesome 1971 drawing by Robert Smithson titled, Toward the development of a Cinema Cavern or the movie goer as spelunker. [Colby’s piece is not online, but Smithson’s complete drawing is at the Estate site.]

According to a contemporaneous Artforum essay titled “A Cinematic Atopia,” Smithson described the project:

What I would like to do is build a cinema in a cave or an abandoned mine, and film the process of its construction. That film would be the only film shown in the cave. The projection booth would be made out of crude timbers, the screen carved out of a rock wall and painted white, the seats could be boulders. It would be a truly “underground” cinema….

Smithson’s interest in cinema was phenomenological: the idea that you sit there, motionless in the dark, experiencing a continuous stream of light and sound patterns. The Cinema Cavern’s closed, self-referential loop devolves into an abstract, multi-colored blur, with the “sluggish,” sloth-like movie goer none the wiser.

Colby puts Smithson’s cinema into context with the Underground-brand cinema of the day, as embodied by Stan VanDerBeek, Jonas Mekas, and friends. Which is fine and all; meanwhile, I’ve added the Cinema Cavern to the list of sketchy Smithson ideas I’d love to see realized here and now.

Part of me–the part who, admittedly, has not delved into the Smithson archives, and thus doesn’t know more than the single sketches–sees the Cavern Cinema as just as fully developed and thus, valid for realization, as, say, Floating Island. And part of me is still smarting for not getting to Les Arennes de Chaillot, the subterranean theater and couscous boite built in Paris by la Mexicaine de Perforation, a group of explorateurs urbains. [read my 2004 LMDP interview here.] And

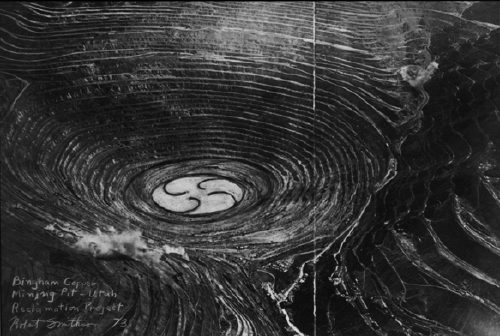

Also on the list: the 1973 Bingham Copper Mining Pit – Utah Reclamation Project. Smithson called for a giant, revolving viewing platform at the bottom of Kennecott Copper’s mountain-sized hole on the western side of Salt Lake Valley, all the better “to survey nature’s gradual and inevitable reclamation of man’s invasive enterprise” with, my dear.

[Every time I fly into Salt Lake, I’m reminded of this drawing/collage, which I rather impulsively bid on–and lost–when it came up for auction in 1993. I later met and became friends with the winning bidder, but I suspect I lost my chance at the drawing; its next stop will most likely be a museum.]

But what if Smithson’s visions already have been realized, and I just didn’t realize it? What if the Cinema Cavern and the Bingham Copper Mining Pit were combined and installed in the post-civilizational, entropic future, offering a front-row seat to nature’s reclamation?

I don’t know if it’s in David Brin’s original mid-80’s sci-fi novel, but in the 1997 film version of The Postman, the dopey title character, played by Kevin Costner, has a showdown with a “hypersurvivalist militia leader named General Bethlehem [played by Will Patton.] In one of the funniest scenes in the unintentionally hilarious fiasco, Bethlehem pacifies his troops–scraggly, murderous slaves who float around on rafts and inner tubes in a giant, water-filled, open-pit mine–with movies. As the battered projector whirs to life, the a battleworn print of The Sound of Music

PDF of “A Cinematic Atopia” in portuguese and english [sescsp.org.br]

Cinema Cavern, 1971 – Robert Smithson Estate – Drawings [robertsmithson.com]

In The Driver’s Seat

Five years ago, someone in North Philadelphia committed suicide by getting hit by the Amtrak train I was riding. I was in the first car behind the engine, where we heard the impact and the aftermath.

I was kind of preoccupied by the incident for some months afterward, and I went so far as to try to identify the person who died, and to inquire with Amtrak about interviewing the engineers and train personnel about what had happened. Though I didn’t necessarily want [sic] to make a documentary about the experience, I found myself using the filmmaking process or conceit as a way to frame and make sense of what had happened. As if making a movie is reason in itself to get into peoples’ lives, losses, and traumas. Anyway, nothing came of it.

And I’m glad, especially after reading the account of Vaughn Thomas in the Guardian. He was driving a train in London when a man stepped off the platform to die.

Last year I killed a man [guardian.co.uk via i forget]

Jeremy Blake’s Video For Beck’s “Round The Bend”

So elegiac. The chandeliers with the painted-on camera flares sequence is particularly beautiful. [youtube via artforum video]

related: Interesting. Paddy put into a coherent statement what I briefly wondered and then forgot: what’s the implication of ArtForum showcasing YouTube videos that have presumably not been sanctioned by the artists who made them?

Paperwork: Gordon Matta-Clark & Public Art

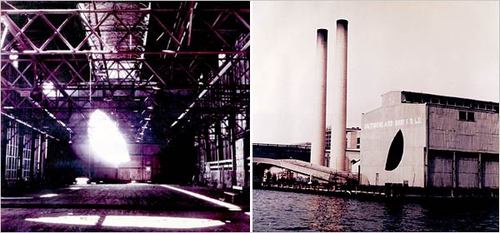

Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1975 film, Day’s End, is on view at MoMA right now. It documents a guerrilla project where he and a couple of collaborators cut a giant, moon-shaped hole in the wall of an abandoned sanitation warehouse on Pier 52, at the end of Gansevoort St in the Hudson River. Matta-Clark said of the necessary illegality of the project:

I had no faith in any kind of permission … there has never, in New York City’s history, with maybe one or two minor exceptions, ever been any permission granted to an artist on a large scale.

via ny mag

Day’s End is also showing at the incomparable Ubu Web. [ubu]

There’s Still A Lot Left Untold In This Article About BYU’s Art Collection Shenanigans

The scale of the scandal of the management of BYU’s art collection was becoming clear just as I entered the art history program there in the late 1980’s. For years, the collection had been ignored by everyone except one professor who served as an ersatz administrator/curator. Without a museum or any galleries to show it in, and without even an inventory or an institutional awareness of what was in it, the collection was just left unattended. Faculty could go grab a Homer drawing or a Rembrandt etching for their offices. The always-open conference room where we met for our contemporary art seminar had a Mark Tobey painting on a hook.

By the time the University announced plans to build an art museum and had begun a computerized inventory, they found that almost 10% of the collection, over 1,200 objects, had gone missing, 900 through theft, fraud, forgery, misplacement, unauthorized sales or trades, or returns to original donors. As this long, fascinating, but maddeningly incomplete article in the Deseret News reports, a couple of folks at BYU have been doggedly pursuing the return of the artworks since 1986.

The story focuses on a couple of high-profile cases where unscrupulous dealers seduced or duped the BYU professor in charge of the collection. A NY dealer named Dion O’Wyatt took a Monet and some Homer drawings from Provo to NYC, ostensibly for appraisal in advance of an unapproved sale. Then he had a street artist copy the works, and he quickly sold the originals. The forgeries went undetected for 16 years.

To their credit, BYU went public and disclosed the full scale of their mismanagement. Al the missing works have been entered into the Art Loss Register. Some works, like a Julian Alden Weir painting now in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection, have been located, but their return or ownership are in dispute. The article has no mention of any of the donors who got/took work back, or of the other dealers or instigators of this fascinatingly obtuse escapade. I’m glad the movie mentioned in the story didn’t get made, but I’d love to read a fuller accounting.

Stolen art — BYU searches the world to recover pilfered pieces [deseretnews.com via mom]

Semiconductor’s Hairy Balls

As the guy married to the officially coolest scientist at NASA, I admit, I took a personal, even a slightly defensive, interest when I read on Gizmodo that

Scientists from NASA’s Space Sciences Laboratory have made [magnetic fields] visible as “animated photographs,” using sound-controlled CGI and 3D compositing. It makes the fields, as explained by the scientists, dance in an absolutely gorgeous movie called Magnetic Movie. You don’t want to miss this one, which is the coolest video that you’ll see all week, guaranteed. You can’t argue with a combo of beautiful effects and amazing science.

Of course, I needn’t have worried. Gizmodo’s is just the most concretely inaccurate description of Magnetic Movie, which was produced by Animate Project. The directors are Ruth Jarman & Joe Gerhardt, a visual performance/sound-film artist duo who work as Semiconductor. It was shown last year on Channel 4 in the UK as part of the Animate TV series

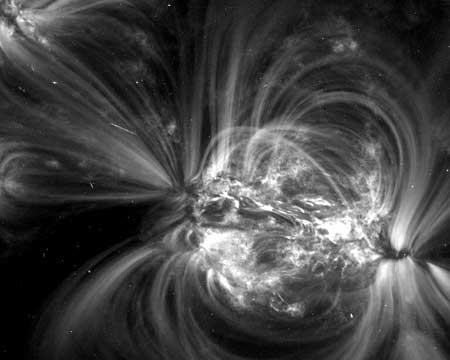

But since Gizmodo’s also among the most influential blogs to have covered the film, its errors have been amplified across the web. Now Semiconductor’s aesthetic experiment is being either passed along as actual science or angrily debunked as fraud. These visceral responses based on some combination of ignorance and misinformation are the inadvertent, negative corollary to Semiconductor’s own creative process. From an interview for Animate Project:

RJ: With Magnetic Movie, it’s a short film we’ve made where we’ve interviewed space scientists about a quite specific subject that they study: magnetic fields.

JG: As the scientists would explain their ideas, their science to us, we could only understand the very beginnings of it, the surface of it. And this leads to a very kind of creative imagination of what it is they’re trying to explain to us.

…

RJ: And so we’ve listened to the scientists’ descriptions, which are very elaborate, and then we’ve tried to make our own interpretation of what these descriptions are. And we’ve created visualizations of these descriptions and placed those back within the Space Sciences Lab.

Semiconductor also tapped SSL for unprocessed scientific imagery of solar flares for their 2006 sound-film, Brilliant Noise, “We’re quite interested in things that go unseen or unheard. And a lot of scientists are dealing with these things and revealing these things to us in new ways,” said Jarman. Only the visual seductiveness of the solar imagery stands in sharp contrast to the lab itself, a shabby series of storerooms populated by a bunch of amiable nerds speaking impenetrable nerdspeak.

The irony, if that’s the right word, is that the real unseen and unheard elements in this world are the bureaucratic dishevelment and the people, the ones who amuse themselves by calling planet-dwarfing solar flares “hairy balls.” And while sound-film artists are by definition different, some of the space scientists I know are actually incredulous about the seen and the heard. When you’re dealing with magnetic fields or high energy particles all day, you work to understand the data in the format you have; the fact that they’re “invisible” is irrelevant.

Just the opposite, the inherent subjectivity and limitations of the human visual and audible spectrums actually makes them suspect. I’ve heard X-ray astrophysicists heave exasperated, skeptical sighs over the attention given to the latest spectacular photos from the Hubble telescope which, they point out, contain next to no useful data, but which are colorized to enhance their aesthetic appeal.

See the Magnetic Movie page at Semiconductor’s site [semiconductorfilms.com]

Brilliant Noise is, but Magnetic Movie is not and on Worlds in Flux, the Semiconductor DVD released last year [amazon]

At the moment, the full 4:50 version of Magnetic Movie is on YouTube [youtube]

After Hours, Frankly

Interesting. The script for one of my favorite Scorsese films, his dark, odd 1985 After Hours, appears to have been heavily lifted from a 1982 performance by Joe Frank, one of my favorite dark, odd radio dramatists. Andrew Hearst has connected the dots, apparently for the first time in print.

Joseph Minion’s script for After Hours began as a screenwriting class project at Columbia. His original title was reportedly Lies, which is the same name as Joe Frank’s piece. The film’s story, the arc, and a whole host of details significant and minor are identical to Frank’s play. According to Hearst and a Salon article on Frank, the writer received a large settlement from the producers, which is certainly the least they could do.

Even more intriguing, though, are Frank’s own references to the plagiarism scandal in a 1986 show titled, “No Show,” which has been performed, aired, or released in 2-hr, 90-min, and 1-hr versions. [There’s mention of a torrent version of the show, but I haven’t been able to find it online.]

In “No Show,” Frank apparently performs phone conversations with Minion, wherein the young screenwriter begs for leniency and help saving his career. Hearst thinks that Minion’s IMDB profile after After Hours is thin, a consequence of being frozen out by the industry. But he still made films with Nicolas Cage and Kathleen Turner, and his current project has Lisa Kudrow attached and producing, so he hasn’t been too blackballed.

Though I’d like it to be true because it’s a perfect, Frank-ian twist, I don’t believe the speculation on the Joe Frank mailing lists that Minion is actually Frank. Though frankly [sic], does Frank-as-Minion actually writing After Hours seem any more implausible today than a SoHo populated by artists and weirdos, yet without cars or ATM’s or more than one place to go at night?

Matthew Barney: Big Bucks, Many Whammies

Christopher Knight didn’t have as bad a time at the performance/filming of Matthew Barney’s “REN” as the audience members who were injured by flying glass when the backhoe went at it with the Chrysler Imperial in the auto dealer showroom:

When paramedics left, the crowd filed into the tomb — actually the car-lined former service bay. Lila Downs, the great Oaxacan ranchera singer, wailed at a corpse laid out atop a golden Grand Am. A “menstrual shroud” was extracted from the loins of a masked nude woman. Somebody said that locusts were released in the parking lot, but I didn’t see them.

Then we all drove home.

It had been a long evening of checking off source materials: Richard Prince, Paul McCarthy, Charles Ray, Kiki Smith, “Cleopatra,” Al Gore, etc. The industrial coupling was pure Survival Research Labs, the Northern California heavy-industrial performance troupe that has been artistically disemboweling the military-industrial complex for 30 years.

Still, most interesting was the crypto-performance going on around the crypto-Egypto main event. Plenty of official cameras promised future “REN” shows, while performance shards were carefully collected.

I used to think that the most interesting thing about Barney’s work was how he made it, or got it made. I’m not surprised that Barney’s pressing his luck in the home the Live Studio Audience.

Matthew Barney’s ‘REN’ [lat via man]

MUTO By Blu

This is awesome, like OG William Kentridge in real space. MUTO is a new stop-action animation by Blu, a Buenos Aires artist, where I guess/hope they have different etiquette about painting over someone else’s art on the street.

MUTO a wall-painted animation by BLU from blu on Vimeo.

blublu.org and blublog [via waxy]