I’m totally with Andy on this one; you should not embed it; you should watch the new ad for the Honda Insight hybrid on the Vimeo site. The sunrise is spectacular.

Meanwhile, as with the making of videos for the Honda Accord “Cog” spot and the Sony Bravia bouncing balls, I will never cease to be amazed at the unalloyed hubris advertising people display for their own–and their paying clients’–activities.

Honda Insight ad – “Let it Shine” [vimeo via waxy]

The Making of “Let it Shine” [vimeo]

Category: making movies

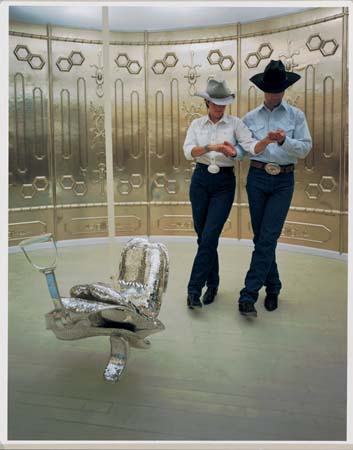

Little Big Cremaster

Awesome. YouTube user fluxlaser has created levels in Little Big Planet based on The Cremaster Cycle. So far, there’s Cremaster 4 [above] and Cremaster 1 [below], which is tighter. I can’t wait to see the mirrored salt flat rodeo in Little Big Cremaster 2. [via waxy]

There’s also this level, based on The Order, the commercial release DVD created from Cremaster 3:

way back in 2003: Matthew Bremsen called it in his article, “Matthew Barney vs Donkey Kong

Meanwhile, Agnes Varda Is Making Installations Now

Agnes Varda, who’s DV mini-masterpiece The Gleaners was formative in my own decision to start making movies, tells Artforum:

I’ve been making films for so long, for over fifty years now, but I really think I have two paths of work–cinema and installation.

Varda talks about an installation opening at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, which was one of several shown previously at the Fondation Cartier.

500 Words | Agnés Varda [artforum.com]

Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Dendur

G — He is an archeologist and an anthropologist. A Ph.D. He’s a doctor, he’s a college professor. What happened is, he’s also a sort of rough and tumble guy. But he got involved in going in and getting antiquities. Sort of searching out antiquities. And it became a very lucrative profession so he, rather than be an archeologist, he became sort of an outlaw archeologist. He really started being a grave robber., for hire, is what it really came down to. And the museums would hire him to steal things out of tombs and stuff. Or locate them. In the archeology circles he knows everybody, so he’s sort of like a private detective grave robber. A museum will give him an assignment… A bounty hunter.

S — If there were these Arabs who just discovered some great king’s tomb, and you see the tomb being taken out. And there are about twenty five or thirty Arabs heavily armed, and like five trucks and you realize… there’s this one guy who’s all painted, and he’s one of the pall bearers who slips a thing into the back of the truck, gets behind the wheel and as the caravan is going to turn right, this one thing goes left. And the rest chase him, but he gets away.

G — The thing is, if there is an object of antiquity, that a museum knows about that may be missing, or they know it’s somewhere, he can go like an archeologist, but it’s like rather than doing research, he goes in to get the gold. He doesn’t really go to find cheap artifacts, he goes to gather stuff. And the other thing is, if something was taken from a tomb, stolen and sort of in the underground, sometimes they may send him out to get it. Essentially he’s a bounty hunter. He’s a bounty hunter of antiquities is what it comes down to.

If a museum says that there is this famous vase that we know exists, it was in this tomb at this time. It may still be there, but we doubt it. We think maybe it’s on the underground market, or in a private collection. We’d like to have it. Actually it belongs to us. We’re the National Museum of Cairo or something. He says okay and tracks it down.

if its not in the thing, he finds it, finds out who’s got it. And he swipes it back. A lot of times it’s sort of legal. All he has to do is get it. It’s not like he steals things from collectors, and then gives them to other collectors. What he does is steal things from private collectors who have them illegally, and gives them back to the national museums and stuff. Or, being that his morality isn’t all that good, he will go into the actual grave and steal it out of the country and give it to the museum. It’s sort of a quasi-ethical side of that whole thing. The museum does commission somebody to go into the pyramids and you know, whatever they find, sort of get out without the Egyptian government knowing, because they were in the process of turmoil and nobody’s going to know anyway and there’s not going to be any official protest, so just do it…

A discussion of the finer points of museum ethics and antiquities collecting from the 125-page, 1978 transcript of George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Lawrence Kasdan’s story conference for Raiders of the Lost Ark [via waxy]

The Ur-Grey Gardens

I discovered the Maysles brothers’ 1975 documentary Grey Gardens in my first semester of busines school. My marketing professor showed us Salesman, and it floored me, leaving me to track down the rest of the Maysles’ work.

So I can’t believe that it’s taken me this long to finally read Gail Sheehy’s 1972 New York article on Grey Gardens and the Edie Beales. I wish I’d found it when I was living in East Hampton; would’ve made those winter nights that much crazier.

scan: The Secret of Grey Gardens, by Gail Sheehy [grey gardens news (!!) via choire]

Ely Kim

Art & Fear by Bayles & Orland

Whether it’s right or not, this book sounds fantastic:

Making art provides uncomfortably accurate feedback about the gap that inevitably exists between what you intended to do, and what you did. In fact, if artmaking did not tell you (the maker) so enormously much about yourself, then making art that matters to you would be impossible. To all viewers but yourself, what matters is the product; the finished artwork. To you, and you alone, what matters is the process: the experience of shaping that artwork.

Art & Fear, by Peter Bayles and Ted Orland [via kottke and kk]

Musical Commentary Track

I caught a few minutes of Joss Whedon on Fresh Air yesterday; for the first half of the show, he was talking about the making of Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, and the awesome-sounding DVD, which includes Commentary! The Musical! the world’s first singing DVD commentary track.

Joss Whedon on Fresh Air, 2/11/2009 [npr.org]

Buy the Dr Horrible DVD at Amazon [amazon]

Come Come Ye Saints

I remember people scoffing at the Mormon pioneer hymn, “Come, Come Ye Saints” because its tune is from some English drinking song. But that just seals it for me as a song written by and for some seriously humbled folks who made tremendous exertions and sacrifices for what they believed in.

But that’s only one reason I’m posting what may just be the greatest cover ever of CCYS. While shooting his documentary New York Doll about Arthur “Killer” Kane, the glam punk pioneer-turned-Mormon, director Greg Whiteley got surviving Dolls David Johansen and Brian Koonin to sing a couple of old school hymns, unplugged. The guitar-and-harmonica arrangement of “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief” runs over the closing credits of New York Doll, and it’s as soulful and rocky as any Rubin-era Johnny Cash.

“Come, Come Ye Saints” is only on the New York Dolls DVD, though. I think. They only sing one verse, the last one, which fits all too well.

Photographing Photographing Dan Graham’s Project For Slide Projector

For their first show in 2005 Orchard, the collaborative gallery/exhibition space on the Lower East Side, recreated Dan Graham’s 1966 Project for Slide Projector:

Project for Slide Projector was presented as a set of instructions for an experimental work and a theoretical text that interrelated minimalist ideas of three-dimensional work with the conventions of photographic representation. Graham published his text in no less than three versions in 1969. In the period 1969- 70, a student of Graham’s at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax realized a set of slides for the work with Graham. To execute the piece, a rectangular structure of four glass panes with an open top and a bottom pane made of mirror was constructed, along with four glass boxes designed to nest within the first box. To create the photographs, a 35mm camera was placed close-up and parallel to the rectangular face of the large box so that the edge of the photograph and the edges of the box align. The camera operator shot each side of the glass and mirror structure, moving clockwise, and did the same as each additional box was added within the larger structure. The resulting set of twenty slides is duplicated in order to produce a set of slides that arrays the images in a forward and back-ward motion as they project.

Over the carousel projection of 80 images, the degree of reflectivity and spatial ambiguity of the mirror space Graham conceived moves cyclically and inverts, building and un-building. Located somewhere between the materials and experiences of sculpture and photography though essential to neither, Project for Slide Projector captures the experience of walking around a sculpture, that is, the spectator’s perception- a site for significant artistic experimentation in the sixties. Project for Slide Projector can also be read as an image of the experience of looking at sculpture via its photographic reproduction, a subject artists such as Robert Smithson explored in visual work, exhibitions, and writing.

Graham wrote: “The sculpture is the photographic residue, and effect of projected light. What is seen must be read in terms of the conventions of still photography: two-dimensional objects which appear at once solid and also as transparent, and which function simultaneously in two entirely different planes of reference (two-dimensional and three-dimensional).” (Films 1977)

Meanwhile, for his film project Orchard 2, Jeff Preiss created a flickering, Muybridge-like animation documenting the process of shooting a new set of slides for Graham’s piece. All that’s left is to download Preiss’ film to your iPhone and play it while you’re watching Project for Slide Projector in a gallery. I miss Orchard.

Part Two | Orchard [orchard47.org]

Photographing PROJECT FOR SLIDE PROJECTOR by Dan Graham at ORCHARD [jprq on youtube]

On Mormon [sic] Art, 31 Jan 2009

The greg.org Unannounced Holiday Break [UHB? Oh wait, that’s already taken] is over.

A month from now, on Jan. 31, I’ll be part of a panel discussing Mormon art and artists at the Sunstone Symposium in Washington, DC. It’s sponsored by Sunstone, a journal of Mormon religious, historical, and cultural thought. [Details and registration info are here.] The panel also includes Lisa Fraser [singer/songwriter], Erin Thomas [writer], and Jonathan Linton [artist/illustrator], and the moderator is Menachem Wecker, a DC-based journalist specializing in religious art.

A month from now, on Jan. 31, I’ll be part of a panel discussing Mormon art and artists at the Sunstone Symposium in Washington, DC. It’s sponsored by Sunstone, a journal of Mormon religious, historical, and cultural thought. [Details and registration info are here.] The panel also includes Lisa Fraser [singer/songwriter], Erin Thomas [writer], and Jonathan Linton [artist/illustrator], and the moderator is Menachem Wecker, a DC-based journalist specializing in religious art.

Since all my fellow panelists are professional artists, I think the organizers wanted me to talk about my film stuff, or the 19th century Mormonism-related screenplay adaptation I’ve been working on, but I didn’t feel I could do that well in a panel. So I suggested–and instead will be talking about–Mormon artists and Mormonism in the contemporary art world. I’m thinking it might be a pretty short talk.

The most prominent references to Mormonism in contemporary art are obviously in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle, particularly in Cremaster 2, where cowboys two-step around the temple in Nauvoo, Illinois, and Gary Gilmore’s parents visit the spiritualist whose table is supported by Golden Plates. As one of the [presumably] few Mormons to actually see Barney’s work, I figure his interest is in symbology and self-contained systems, and that Mormonism is just another source, like football and Freemasonry, from which he constructs his own hermetic world. If I see Matthew before I speak, I guess I’ll finally ask him if he was actually raised in the church, or if being from Boise is enough to make anyone an honorary Latter Day Saint.

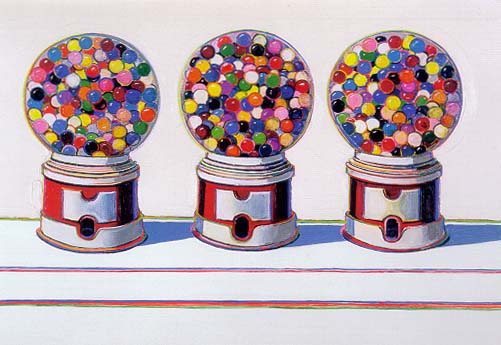

But my main focus is on the three major artists whose Mormon connection is uncontested–and for the most part, unconsidered: Wayne Thiebaud, Paul McCarthy, and La Monte Young.

[above: a trailer (?!) for a 2007-8 McCarthy exhibition in Ghent, maybe nsfw]

Typing those three names next to each other, I can’t think of a more dissimilar-seeming bunch. It seems the only thing they have in common is that they grew up Mormon in the West–Thiebaud in Los Angeles and Southern Utah, McCarthy in Salt Lake City, and Young in rural Idaho–and they all left the Church.

Also, they’re all old. Thiebaud and Young were both born in the Depression [I guess I should get used to saying “the last Depression”], and McCarthy was born in 1945. I tried and couldn’t come up with another prominent artist in the contemporary art world with Mormon connections or roots born since WWII. Though there are a few artists showing in New York these days with LDS connections–Lane Twitchell, my brother-in-law Benjamin Cottam–it does seem that there’s at least one missing generation.

I’ll be researching and posting a bit about this [dis]connection between Mormons & contemporary art over the next few weeks. If anyone has any thoughts, particularly if you want to out your favorite Baby Boomer artist as a Mormon, I hope you’ll drop me a line.

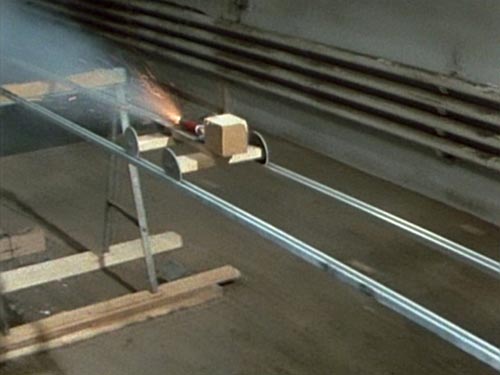

Astute And Observant Viewers Get Fischli & Weiss

It just keeps going and going! From Steven Kaplan emailed with a reply from MoMA curator Christian Rattemeyer about the consciousness of edits in Fischli & Weiss’s Der Lauf der Dinge: “It is his contention that many astute and observant viewers (himself included) have ‘always thought of it as an edited work, never as a continuous chain reaction.'”

D’oh! If you need me, I’ll be over here in the unastute and unobservant section, reading People. But to Kaplan’s–and by extension, Rattemeyer’s, and the entire observant art world’s–point, I didn’t mean to imply that Fischli & Weiss have duped anyone, or that they or any institutions are mis-presenting the piece.

Editing is basic to the language of film, so basic, in fact, that it often disappears from our consciousness. That’s just the way things go. Just as Fischli & Weiss’s meticulously fabricated re-creations of a custodian’s closet, Der Lauf der Dinge‘s impact derives from its seemingly artless [sic] matter-of-fact-ness. It looks and feels like a documentary, just a guy with a camera capturing the way things go. But it turns out to be a film that–like any other film–is the careful culmination of a whole host of aesthetic decisions, both on the set and on the editing table. Maybe the editing point is so obvious, it doesn’t need to be made, but I guess I’m simpleminded like that.

[update after thinking about it: Though F&W’s edits are not cuts, the kind of jumps of time, place, or vantage point we’ve come to read unconsciously as film; they’re almost all illusionistic, dissolves and fades, that attempt to approximate continuity.]

Rattemeyer also brought a show at Susan Inglett Gallery to Kaplan’s attention, titled “The Way Things Go,” in obvious homage. It closes tomorrow, so I’ll have to content myself with the press release and images.

The Way Things Go, through Dec. 20 [inglettgallery.com via thing.net]

Vik Muniz Gets Fischli & Weiss

I’ve been searching for more critical acknowledgment of Fischli & Weiss’s Der Lauf der Dinge as an edited construct instead of the miraculous documentation it’s normally perceived/presented to be.

Though he’s talking about another Fischli & Weiss piece [above], artist Vik Muniz, who just curated Der Lauf der Dinge into “Creating a Rebus,” his show at MoMA, nails some very relevant aspects of the duo’s work:

It’s about this connection between mind and matter — how something is conceptual and formal at the same time. Fischli and Weiss are artists that I admire for this: They manage to put an enormous amount of craft into their illusions. I remember when I first saw this piece at Sonnabend Gallery, people didn’t think these objects were constructed, but they are all cast pieces. It takes a lot of labor to make something look accidental.”

Vik Muniz on Creating a Rebus [artinfo.com, image: matthew marks gallery]

update: In a short podcast with Mexican artist Pablo Helguera, Hirshhorn curator/researcher Ryan Hill mentions F&W’s dissolves a couple of times, and how exhibiting the film on a loop can trap visitors who keep watching the procession go round and round. I don’t know why there’s no way to search, sort of link directly to the many, many podcasts on Hirshhorn’s site, but here’s the mp3 file [hirshhorn.si.edu]

Der Kauf Der Dinge

Artforum reports that Fischli & Weiss’s 1987 film, Der Lauf der Dinge, (The Way Things Go), [1] was recently sold at Christie’s in Zurich for 1.02 million Swiss francs. Which is awesome [2], I first thought, since I have that work, and I only paid $20 for it. [d’oh, it’s only $15 on amazon!]

Of course, the Dinge that sold was not the DVD, which is available all over, or even the exhibition copy, which is always a crowdpleaser at museums. [It’s pleasing crowds right now in one of the Hirshhorn Museum’s hallways interstitial spaces, in fact. update: and Vik Muniz put it in the hallway of his show at MoMA, too. Thanks Steven, Tyler, Maggie and Melanie for the tip.] Instead it was, in Artforum’s words, “the original film reel along with a series of relics from the film set.” They said as they cranked up the music and danced on Walter Benjamin’s grave.

Before seeing the making of video for “Cog,” Weiden + Kennedy’s insane, single-shot 2003 Honda Accord commercial which knocked off Fischli & Weisswith spectacular effort and precision [3], I hadn’t given much thought to the making of Der Lauf der Linge or how it existed as a work of art; I just thought it was what it obviously was.

But now it wasn’t so obvious. It had taken W+K 606 takes to get their 2-minute sequence perfect, and even that turned out to have been edited. [It’s really two one-minute sequences edited together where the muffler rolls across the floor. Watch the floorboards.]

Sure enough, there are edits all through Der Lauf der Dinge, mostly dissolves executed by taking the camera in close to something abstract–a spinning garbage bag [2:00] or a pool of foam [2:55, 3:43] smoke from dry ice [7:22], more foam [9:31]–or something abrupt and distracting–the flare of a lightbulb [11:09], the firework exploding on the side of a tire [12:04], a flare of a fuse [13:21] or a candle [13:47] [4]. If F&W had had script girl on set, she might have noticed that a fuse appears out of nowhere at the edge of the flaming pool [14:11], or that the lighting is significantly darker in the second shot.

Actually, that 14-min. cut marks something of a second act. The sequences that follow are all darkly lit, which accentuates their flames and fireworks. There are two more hard-to-spot cuts [15:51, burning hay], [17:26 bucket glare] before a bold, smoky dissolve [18:33] and an even more conspicuous–well, it’s really a montage, what else can you call it?–set of a weighted doll-like device tottering off a plank [19:17]. A dissolve in the blackness at the center of a wheel brings the lights back on [20:18]. More pools of flame on the floor [21:28]. Explosion under a teapot [21:51]. The close-up foam dissolve is now an official motif [22:22, 23:33]. As is the flame-on-floor [24:57]. And the dry ice [25:25].

They’re reusing props, too. The orange board that was so obviously being manipulated off-camera [8:00] is now a simple ramp [20:40]. And there’s that air mattress [1:15], now turned and folded [26:00]. Foam [27:00]. Smoke [28:54] whoa, fade to black. [29:02] the end. An edit to nothing, effectively.

23 edits in a 29 minute film, including one seemingly unnecessary one at the very end. Re-used and staged props. If you studied the walls carefully, you’d see the devices are not wrapped around a giant factory, but are staged in the same general strip of space. It turns out The Way Things Go is not the way things are purported to go. Which made me wonder who’s doing the purporting, and who’s doing the assuming?

The artists and their production companies and distributors seem happy to perpetuate the idea that Der Lauf is one, giant, continuous Lauf. Here’s the copy on my DVD case:

Inside a warehouse, artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss build an enormous, precarious structure 100 feet long made out of common household items…Then, with fire, water, gravity, and chemistry, they create a spectacular chain reaction…

Guess they forgot to mention the editing. I haven’t found reactions to the film’s debut in the summer of 1987 at Documenta 8, but when it was first shown in the US, at PS1 in 1988, the NY Times critic marvels at the duo’s “masterpiece to date,” where “the artists manage to sustain a chain reaction of ever-more-absurd materials and events for 30 minutes.”

The edits are clear, even obvious in places, and yet casual observers and critics alike appear to miss or ignore them, preferring the enjoyable spectacle of a 30-minute, non-stop trick. I’ve never heard of this dichotomy discussed in terms of Fischli & Weiss’s work, certainly not in regard to this piece. A cynic could have a lot of fun with the idea that people choosing to believe something enteraining but self-evidently false is, in fact, The Way Things Go.

I should have mentioned much earlier that all my Der Lauf der Linge questions might already have been answered. This whole post might be another in an embarrassing series of RTFM-themed posts, where I could just get the damn book and find out what’s going on. Jeremy Millar wrote a book-length paean to The Way Things Go, the publication of which coincided with a 2006 Fischli & Weiss retrospective at the Tate, which went to Hamburg and Zurich.

And then there’s Making Things Go, a making-of documentary by ex-critic/curator Patrick Frey, who had filmed his friends Fischli & Weiss in 1985 experimenting [rehearsing?] with their various entropic stunts and devices. Though, reading Frey’s account in Tate Magazine, the answers may not be there at all:

The first version was a relatively short loop, which Fischli/Weiss call Sketch for The Way Things Go: a three-minute Super-8 film, in which key sequences of the later 30-minute 16mm film are outlined and tested.

The present film documentation was created during the three-day preparations for this ur-version of The Way Things Go.

Christie’s engaged Frey to lecture on Der Lauf der Dinge as part of the pre-auction excitement, but I haven’t found an account of the event online.

But back to the other anomaly, the “originality” of the million-franc version of Der Lauf der Linge. The piece Christie’s sold was from the collection of Alfred Richterich, and though the auction house’s press release [pdf] includes lofty quotes about Richterich’s foundation using the proceeds to support new generations of Swiss artists, there is no mention at all about his own apparently seminal relationship to the film–even though it seems intrinsic to the existence and nature of the work itself.

Richterich is an heir to the Ricola cough drop empire, such as it is, and he pursued his family’s tradition of collecting art and supporting various creative endeavors. According to the monograph of Herzog & deMeuron, who received early commissions from Richterich, he was “instrumental in facilitating” the production of Der Lauf der Linge. Sure enough, Richterich’s film production company is credited on my DVD case, right alongside T & C Film, the production company who provided the crew–and who had produced Fischli & Weiss’s with their earlier film projects.

I had always assumed that Matthew Barney pioneered the art of financing films by packaging props into more easily monetizable vitrines, but Fischli & Weiss had him beat by a full Documenta.

Did Richterich receive a somehow definitive version of Der Lauf der Dinge along with his two vitrines full of ephemera in exchange for funding the production? Was his film reel more “original” than the prints that museums and collectors used before the advent of decent video transfers? Is it the artists’ actual negative or master print? Or is the market’s throwback preference for “objects” as opposed to “art”–even when it comes to the sale of this “icon of Swiss art”–just the way things go?

[1] the artist’s chosen English title is The Way Things Go, which lacks the flowing, riverlike connotation of the direct translation, The Course of Things or The Current of Things.

[2] Of course, it’s slightly less awesome for Christie’s and Richterich, because the pre-sale estimate was CHF1-1.5 million. With premium and VAT, I calculate the hammer price at CHF 790,000, which is an odd increment and well below the low estimate. Looks like even the “icon of Swiss art” market is down these days.

[3] Whatever its knockoff-ish crimes, “Cog” is rightly praised as one of the greatest commercials ever made. It took dozens of people months to design, engineer, and produce. It involved taking apart one of just six pre-production Accords in existence, cars that had been hand-built by Honda. In fact, I’m going to watch it again right now, I’m so jazzed by writing about it.

[4] this one is almost a jump cut; the camera ends up on the other side of a metal sawhorse when the candle ignites its target.

Billy Bitzer Rides The Train

Before he became the first cinematographer in Hollywood[land], and before he helped fund D.W. Griffith’s Birth of A Nation, Billy Bitzer worked for the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in New York, making actualities, basically documentary shorts.

Like this one from 1905, which follows a subway from 14th st to 42nd st. Kottke reports the chatter that it’s the Lexington line, which makes sense. I remember reading some plaque about how the Lexington line is the oldest in the city, and was built by excavating the street, then covering it up. Both from the bracing and the ceiling height of the tunnel above, it looks about as old and rickety as a subway could look.

Also, the Biograph offices at the time were at 841 Broadway, at 13th.

And Joshua points out a romantic coda from Alan Weisman’s book, The World Without Us: “should humans disappear, Lexington Ave. would shortly cave in (presumably because of the subway), creating a huge river that would flow through the center of the island (again).”

rvr vu! [via tmn]

Billy Bitzer [biographcompany.com]