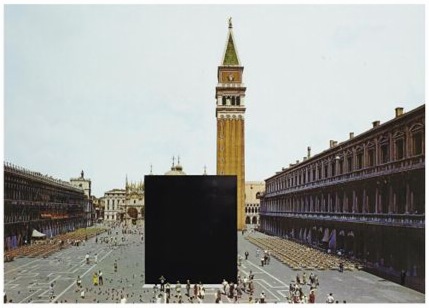

Buy this nice c-print study of Gregor Schneider’s unrealized Cube Venice at Sotheby’s next month, and they’ll throw in a fatwa for free!

Sale L09621, Feb 6, 2009, LOT 213: GREGOR SCHNEIDER, CUBE VENICE, 2005, numbered 2/6, 3,000–4,000 GBP [sothebys.com]

Category: satelloons

For The Record, I Am Not Daniel Young & Christian Giroux

Though with their combination of Ikean sculpture, reconstituted Cold War satellites, and geodesic dome playthings, I’m now not sure I’m not actually just a random projection of their collaborative imagination.

Daniel Young and Christian Giroux began making work together in 2004. The first collaboration was Fullerene, a giant, but light mobile structure of aluminum and bicycle tires that the duo rolled around Scope Miami in 2004.

Then in 2006, they showed a trio of sculptures that took the forms [and names] of US, Canadian, and Soviet spy satellites from the 1960’s. [Quirky Canada has own laws, spy satellites!] Both the spherical Fullerene, and the satellite shapes, which were originally designed for gravity-free orbit, are pleasantly disorienting riffs on the Minimalist sculptural challenges of Judd & others, who rejected a base, thereby launching objects into space.

And then this past summer, the duo’s show at Diaz Contemporary in Toronto consisted of sculptures made from custom-fabricated aluminum boxes and Ikea tables. They’re like narrower, harder-edged, and Juddier echos of Rachel Harrison’s and Isa Genzken’s sophisticated pastiches. And I mean that in the best possible way.

Daniel Young & Christian Giroux – Work [cgdy.com via tagbanger]

PAGEOS: Second Generation Satelloon For Stellar Triangulation

When I first discovered satelloons a few months ago, I admit, I was a little disappointed to have fallen so hard for the first generation satelloons of Project Echo. This disappointment kicked in when I saw this photo of the PAGEOS satelloon being tested before its June 1966 launch. It wasn’t much bigger than Echo I [31m vs 30m; Echo II was 40m]; what set it apart was PAGEOS’ incredible mirror-like skin.

Which, I find out, was by design. PAGEOS, short for PAssive GEOdetic Satellite, was used in the impressive-sounding Worldwide Satellite Triangulation Network, an international collaboration to create a single global characterization of the earth’s surface, shape, and measurements.

Geodesy, the science of measuring and representing the earth, helped identify things like plate tectonics and the equatorial bulge. From what I can tell, the WSTN involved taking pictures of the PAGEOS against identical star fields from different points on the earth’s surface, then backing out precise values for latitude, longitude, and elevation from the photos’ variations.

Stellar geodesy was obsoleted during PAGEOS’ lifetime by lasers [more on that later], but not before the WSTN, under the direction of the Swiss scientist Dr. Hellmut Schmid, was able to calculate the accuracy of locations on the earth’s surface to within 4m. According to Wikipedia, between 1966 and 1974, Schmid’s project, using “all-electronic BC-4 cameras” installed in 46 stations around the free world [the USSR and China were not participating for some reason], produced “some 3000 stellar plates.” Photographs of the stars with a 100-foot-wide metallic sphere–designed to capture and reflect the sun’s light, and placed in an orbit that provided maximum visibility–moving in front of them.

I’d love to see some of these plates, or find any useful reference sources beyond the kind of scattershot, autotranslated Wikipedia articles.

Balloon Satellite [wikipedia]

PAGEOS

Stellar Triangulation

Hellmut Schmid

This Week in Satelloon-Lookin’ Art News

Macy’s has installed Jeff Koons’ 53-ft tall Bunny balloon in its Chicago store [f/k/a Marshall Fields] in conjunction with the Koons retrospective at the MCA. Katnp has more Bunny photos on flickr.

Les Satelloons Du Grand Palais

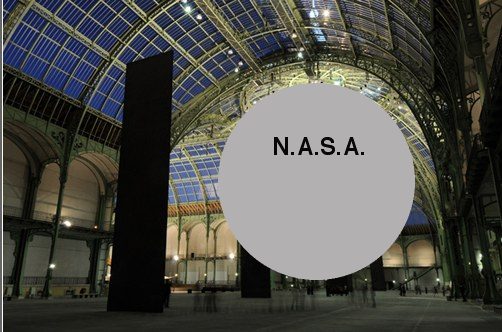

Promenade is Richard Serra’s commission for Monumenta, the contemporary arts program inaugurated last year in the nave of the newly restored Grand Palais in Paris.

Serra’s work consists of five 17×4-meter steel plates set vertically along the central axis of the Grand Palais. The size of the slabs was determined in part by technical limitations of the steel mill, and in part by the dimensions of the massive, open space itself: 35m high, rising to 60m at the cupola, 50m wide, and 200m long.

So Serra Schmerra, that means the Grand Palais is big enough to exhibit my re-creation of NASA’s satelloon. At least the Project Echo I, which was 100 feet in diameter. [Echo II was 135 feet, which might be a tight squeeze.] Unlike with the other two indoor venues capable of housing the work, the Pantheon in Rome and Grand Central Station in Manhattan, Monumenta gives the Grand Palais the advantage of a pre-existing, curated contemporary art context.

In recent high-profile museum building projects from the Guggenheim Bilbao to MoMA, Richard Serra’s multi-ton sculptures have been the default unit of measure; floors must be able to bear and spaces must be able to accommodate a Serra. The continued utility of such Serra Unit-based architecture. Just as screen-based art tests the programmability of art spaces, presenting a gigantic yet inconsequentially light object like a Satelloon as an art object poses an exhibition challenge of a different scale.

Here is a rough artist’s conception:

Now all I need to do to exhibit the Satelloon in Paris is to develop a body of work and a career comparable to Serra’s and last year’s Monumenta artist, Anselm Kiefer. So yeah, let me get right on that.

Hal Foster on Serra at the Grand Palais [lrb]

Monumenta 2008, including photos from the opening by Lorenz Kienzle [monumenta.com]

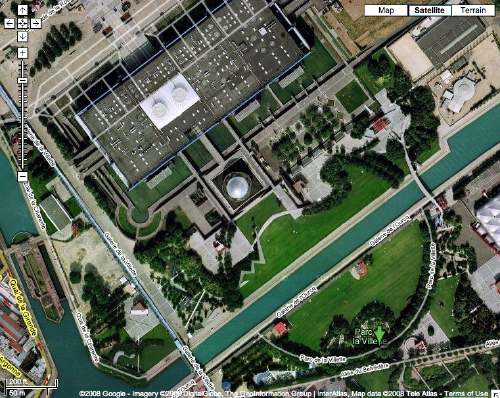

Ceci N’est Pas Un Satelloon

But darned if it isn’t pretty damn close. La Géode is a mirrored geodesic dome housing a hemispheric Omnimax theatre. It’s part of the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, a science museum opened in 1986 in Parc la Villette, which I confess, I only knew as the site of Bernard Tschumi’s red follies. [There are a couple visible in the background here, and judging from this photo from another angle, they’re rightupthere next to the dome.]

At 34m across, Adrien Fainsilber’s stainless steel-clad Geode is the nearest approximation to the physical presence of a Project Echo satelloon that I’ve found. [Thanks to Stuart, actually, who tipped me to the recent post on extremely impressive shiny balls on deputy dog.]

Fainsilber’s site has more pictures, including the grainy-nice snap of the Geode nearing completion. and this amusing explanation:

Symbole de l’Univers, le reflet des nuages suggère la forme des continents et offre une vision immatérielle de l’environnement.

L’écran hémisphérique de 26m de diamètre de la salle de spectacle a engendré la forme sphérique de l’enveloppe.Symbol of the Universe, the reflection of clouds suggests the form of continents, and offers an immaterial vision of the environment.

The hemispheric screen of 26m diameter in the salle de spectacle [heh] engendered the spherical form of the envelope

I love it, a loopy mix of grandiose over-symbolism and bureaucrat-pleasing rationalization. As if the shiny steel awesomeness of the dome was somehow just the unavoidable by-product of the program the humble architect received. [Qu’est ce qu’on a pu faire? C’est logique.] Sure beats the “but it’s art!” pitch that was the last straw for the suits backing the Pepsi Pavilion.

Also, it’s an amusing stick in the eye of the deconstructionist, “form before function” conceit that Tschumi and collaborator [sic] Jacques Derrida put forward for the rest of the park.

I don’t know the story of the creation of Parc de la Villette, but Tschumi sounds like the Robert Irwin to Fainsilber’s self-important Richard Meier. Looking at the landscaping, la Geode has gone from being a Symbol of the Universe to just one stop of Tschumi’s David Rockwellian Cinematic Promenade. Or to the electron on a hydrogen atom. Which, as I zoom in with the all-seeing Google Eye to watch the picnickers in the Parc, i realize is so true. What if the whole universe were just an atom under the fingernail of a giant?

extremely impressiv shiny balls [deputydog.com]

Fainsilber > Realisations > CSI [fainsilber.com]

CSI and la Geode, and guests reading Le Monde, apparently, and letting their kids run wild [google maps]

Metaphysics of Parc de la Villette [gardenvisit.com]

Sata-Koons

Alright, the clock is ticking, only hours to go until Jeff Koons’ largest work to date, a 53-foot high balloon based on his 1986 sculpture, Rabbit, bobs down the west side in Macy’s parade. It was made using a new material intended to replicate the original sculpture’s mirror-like stainless steel surface. Said Koons in a Macy’s press release, “I think one of the reasons why Rabbit is an iconic work, a popular piece, is because it’s so reflective. It reflects the needs of culture and society and can represent so many different things to the viewer.”

Courant’s critic wonders what I wondered, which is what other art balloons have been in Macy’s “Blue Sky Gallery” series? I can’t find any previous artists mentioned.

Anyway, Gallery or not, the Satelloon would not be able to appear in Macy’s parade; Manhattan’s avenues were laid out to be 100 feet wide, the same as the Satelloon itself. What with the streetlights and trees and whatnot, it just wouldn’t fit.

Still, I hope it’ll make a nice, intimate venue for Koons’s modestly scaled work.

Money quote: “A giant silvery rabbit that looks like a massive bunny-shaped UFO? [courant, also top image]

Rabbit inflation test shot via fashionweekdaily [fashionweekdaily.com]

Previously: The Satelloons of Project Echo

If I Were A Sculptor, But Then Again…

Cabinet’s Got Huge Balls

The Joshua Foer photo timeline, “A Minor History of Giant Spheres,” that got me all hopped up on Satelloons, is now online. It’s in the latest issue of Cabinet Magazine.

And while you should always buy or subscribe to Cabinet, the photos online are, on average, much bigger. The curse of the printed timeline format, I guess. [via kottke]

Previously: I will someday install a Satelloon in Grand Central Station, the Pantheon, and/or the Piazza San Marco.

“the most beautiful object ever to be put into space”

If I Were A Sculptor, But Then Again…

Yes, I do have a ton of other things I should be doing, but I can’t seem to get Project Echo out of my head. I really want to see this, 100+ foot spherical satellite balloon, “the most beautiful object ever to be put into space,” exhibited on earth. But where?

When MoMA was designing its new building, a lot of emphasis was placed on the contemporary artistic parameters that informed the structure. The gallery ceiling heights, the open expanses, the floorplate’s loadbearing capacity, even the elevators, everything was designed to accommodate the massive scale of the important art of our time: Richard Serra’s massive cor-ten steel sculptures.

And they did, beautifully, until just a few days ago.

But is there anything more anti-Serra, though, than a balloon? Made of Mylar, and weighing a mere 100 pounds? And yet at 100 feet in diameter, a balloon of such scale and volume, of such spatially overwhelming presence, it dwarfs almost every sculpture Serra has ever made?

The original Echo I was launched into space, but it was explicitly designed to be seen from earth. It was an exhibition on a global scale, seen by tens, maybe hundreds, of millions of people over eight years. People from the Boy Scouts to the king of Afghanistan organized watching parties. Conductors stopped mid-outdoor concert when Echo passed overhead.

L: Hayden Planetarium = 87-ft diam. R: Pantheon = 142-ft. HEY!

What would an Echo satellite do to the art space it would be exhibited in? Are there even museums or galleries who could handle it? Or is the physical plant of the art world still organizing around the suddenly smallish-feeling sculptures of, say, Richard Serra?

Echo satelloons were first seen–or shown, isn’t that why there’s a giant NASA banner draped across it?–in a 177-foot high Air Force blimp hangar in North Carolina. There are plenty of non-art spaces where an Echo could be exhibited, but that misses the whole point.

What art spaces in the world are able to physically accommodate an 10-story high Echo? A gallery or museum would need unencumbered, enclosed exhibition space of at least 120 feet in every dimension:

Suddenly all these atriums and rotundas you think are just grossly oversized turn out to be too small. I guess the art world’s space limitations will be the constraining parameter for my Project Echo exhibition.

Maybe the only thing to do is to show it in a non-art-programmed space after all. Grand Central Station’s concourse is 160 feet wide and 125 feet high in the center. And as a bonus, a US Army Redstone rocket was exhibited there in mid-1957 [via wikipedia]. It was lowered through a hole cut in the constellation-decorated ceiling.

And then there’s the Pantheon, which is built on a 142-foot diameter sphere. As readers of Copernicus, Walter Murch, and BLDGBLOG will know, the Pantheon “may have had secretly encoded within it the idea that the Sun was the center of the universe; and that this ancient, wordless wisdom helped to revolutionize our view of the cosmos.” What better venue for displaying a satellite which indirectly helped revolutionize our view of the origins of the cosmos? And not that it’s necessary, but it even already has a hole in the roof.

Unless I do it outside, Maybe in the Piazza San Marco, where Gregor Schneider’s 46-foot, black, shrouded Venice Cube sculpture was supposed to be installed during the 2005 Biennale. But would a recreation of a relic of American military and media propaganda be any more welcome in Venice than a replica of the Kab’aa? [So I just follow Schneider and install it two years later in the plaza in front of the Hamburg Kunsthalle? I’ll get right on that.]

Or maybe the answer’s right in front of me, and I just don’t want to admit it. Here’s what I wrote last winter about the Sky Walkers parade staged last December by Friends With You [and sponsored by Scion!]

It’s what I’ve always said Art Basel Miami Beach needed more of: blimps.

The only art world venue which can accommodate a 100-foot satelloon is an art fair.

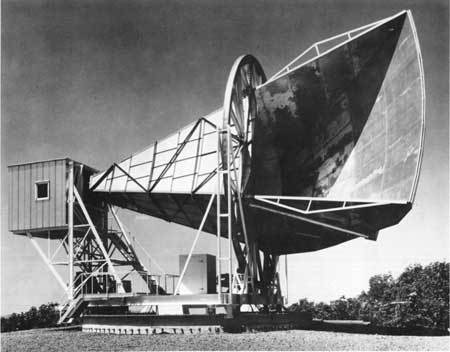

Also of interest: A 1960 Bell Labs film, The Big Bounce, produced by Jerry Fairbanks, tells a very Bell-centric version of the Project Echo story. That horn antenna is something, though. [archive.org, via Lisa Parks’ proposal to integrate satellites into the traditional media studies practice]

The Satelloons Of Project Echo: Must. Find. Satelloons.

From about 1956 until 1964, US aeronautics engineers and rocket scientists at the Langley Research Center developed a series of spherical satellite balloons called, awesomely enough, satelloons. Dubbed Project Echo, the 100-foot diameter aluminumized balloons were one of the inaugural projects for NASA, which was established in 1958.

In his 1995 history of NASA Langley, Space Revolution, Dr. James Hansen wrote:

The Echo balloon was perhaps the most beautiful object ever to be put into space. The big and brilliant sphere had a 31,416-square foot surface of Mylar plastic covered smoothly with a mere 4 pounds of vapor-deposited aluminum. All told, counting 30 pounds of inflating chemicals and two 11-ounce, 3/8-inch-thick radio tracking beacons (packed with 70 solar cells and 5 storage batteries), the sphere weighed only 132 pounds.

For those enamored with its aesthetics, folding the beautiful balloon into its small container for packing into the nose cone of a Thor-Delta rocket was somewhat like folding a large Rembrandt canvas into a tiny square and taking it home from an art sale in one’s wallet.

The satelloons were made from a then-new duPont plastic film called Mylar, which was micro-coated with aluminum using a then-new vacuum vaporizing technique developed by Reynolds Aluminum Co. Originally conceived as research tools to collect data on the density of the upper atmosphere, the reflective satelloons also served as proofs of concept for space-based commmunications systems.

The original research proposal put forward by a Langley engineer named William J. O’Sullivan called for a 20-inch balloon, which was increased to 30 inches. These “Sub Satellites” were followed by a 12-foot diameter Beacon satelloon, the size of which was determined, not by any scientific requirements, but by the ceiling height in the Langley model fabrication room.

In the post-Sputnik euphoria of a 1958 congressional hearing at which a Beacon was inflated in the Capitol Building, O’Sullivan assured politicians that a communications satelloon “10 stories high” could be readied and launched very quickly which could be used “for worldwide radio communications and, eventually, for television, thus creating vast new fields into which the communications and electronics industries could expand to the economic and sociological benefit of mankind.” Such a large, American satellite would also be visible to the naked eyes of everyone in the free world and in the rest of the world. Just like Sputnik, only much, much bigger. It was these 100-foot satellites which were called Echo; the rocket system that would launch these giant balls into space was called Shotput.

l: nasa. r: flight spare at nasm

With this exponential increase in scale, NASA’s Project Echo team faced major engineering challenges in packing and deploying the satelloon. They eventually devised a two-piece spherical payload container laced together with fishing line and ringed by a small explosive charge, which would deploy the balloon.

Then there was the issue of seams. At a 1959 inflation test in a disused blimp hangar in Weeksville, North Carolina, the original General Mills Echo split apart. A photo in Hansen’s book shows O’Sullivan and his colleagues sticking their heads through a gash of the collapsing balloon. The top photo is from a later 1959 test, also at Weeksville.

Folding was another major challenge. G.T. Schjeldahl, the Minnesota packaging manufacturer contracted to build the Echo satelloons after General Mills, had the adhesive question solved, but they couldn’t figure out how to fold the thing. [Founder Gilmore Schjeldahl is credited with creating the first air sickness bag in 1949. In the 1950’s, his company also made inflatable buildings known as Schjeldomes.]

After watching his wife unfold a tiny plastic rain bonnet, however, Ed Kilgore had a “Eureka moment,” which set Langley’s technicians in motion:

At Langley, Kilgore gave the hat to Austin McHatton, a talented technician in the East Model Shop, who had full-size models of its fold patterns constructed. Kilgore remembers that a “remarkable improvement in folding resulted.” The Project Echo Task Group got workmen to construct a makeshift “clean” room from two by-four wood frames covered with plastic sheeting. In this room, which was 150 feet long and located in the large airplane hangar in the West Area, a small group of Langley technicians practiced folding the balloons for hundreds of hours until they discovered just the right sequence of steps by which to neatly fold and pack the balloon. For the big Echo balloons, this method was proof-tested in the Langley 60-foot vacuum tank as well as in the Shotput flights.

The first Shotput flight occurred almost exactly 48 years ago, in the late afternoon of October 28, 1959. The launch and deployment were successful, but the Beacon exploded, most likely due to residual air left in the balloon to aid its inflation in the vacuum of space. The result was a spectacular, 10-minute light show all along the east coast of the US as “the thousands of fragments of the aluminum-covered balloon…reflected the light of the setting sun.”

To uncover the cause of any future failures, the engineers coated the inside of each satelloon with red fluorescent powder. Then they set up a 500-inch focal length camera on the beach near the launch site to document the unfurling in space. They also publicized the launches well in advance, so they could get mitigate any negative publicity of an explosion–and possibly get some credit for another light show.

Echo 1 was destroyed when its rocket failed. Echo 1A, which was commonly known as Echo 1, was successfully launched August 12, 1960. Bell Labs in Holmdel, New Jersey beamed a radio message from President Eisenhower to it on its first orbit, which was reflected back to the world:

This is President Eisenhower speaking. This is one more significant step in the United States’ program of space research and exploration being carried forward for peaceful purposes. The satellite balloon, which has reflected these words, may be used freely by any nation for similar experiments in its own interest.

To communicate with the Echo satelloons, Bell Labs built a 50-foot long horn-shaped antenna in Holmdel, which could rotate and pivot on several axes. Later, in 1964, while calibrating the antenna, Drs. Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson detected microwave background radiation, the first concrete evidence of the Big Bang theory. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1978.

Echo II was launched in 1964. Both Echo satelloons stayed aloft for years [until 1968 and 1969, respectively] Though not very efficient, their passive communications technology spurred on the development of active signal-transmitting communications satellites like Telstar. An Echo II was exhibited at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, and a folded backup is on display at the National Air & Space Museum.

I’ve highlighted some of the aesthetic or non-scientific elements from Hansen’s long, somewhat rambling but detailed chapter on Program Echo to make a point. Or more accurately, to pose a challenge. In the art world, thanks in no small part to Duchamp, we privilege intentionality above all; anything–even the most mundane or found object, situation, and action–is art if the artist declares it to be so. But nothing else.

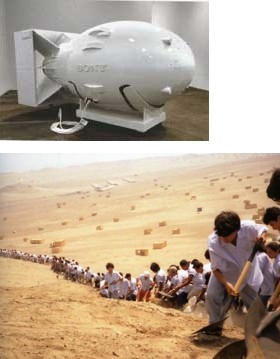

Rirkrit Tiravanija cooking curry; Anish Kapoor employing an engineering firm to build a giant tension-fabric cone or a polished steel parabolic mirror; Michael Heizer etching patterns on the desert with his motorcycle tires; Cai Guo-Qiang exploding an arc of rainbow-colored fireworks across the East River; Tom Sachs replicating Fat Man for Sony; Francis Alys contracting hundreds of laborers to move a mountain of dirt one foot to the left.

How does the remarkable historic, political, cultural, aesthetic, performative, and conceptual achievement of NASA’s Project Echo fit into the cash-and-carry art world? Or, because I’m sure NASA, et al could not care less, and it’s really the art world’s problem, how does the collectively accepted framework of the art world deal with the fantastic, innovative, creative, and life-changing realities of the world around it?

The continent-spanning light show? The largest minimalist sculpture to ever orbit the earth? The hundreds of hours spent folding balloons in a bricoleur’s clean room? The meticulously choreographed performance of folding it? The stop-action artifacts of exploding powder bombs? The emotional and political manipulations of narratives of success and failure, and the rush of collective ego-boosting as a country watches from their porches for Echo to pass overhead?

In practice, product, experience, and impact, Project Echo is every Tate Turbine Hall project, plus half the Turrells [OK, maybe not Roden Crater], plus Happenings, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, the Wilsons, Sachs, Murakami, Rhoades, Mir, Hayakawa, deMaria, Kapoor, Semmes, Hirshhorn, Hamilton, and more rolled–or should I say folded–into one.

And yet has anyone outside the space stamp collecting community even heard of Echo 1 before Cabinet Magazine published a tiny photo of it in their current issue? I’m an art collector married to a satellite-building NASA astrophysicist, and the whole store party atmosphere of the art fair/biennial circuit’s never felt more like a giant, hermetic NetJets conspiracy than it does right now.

Frankly, I’d rather track down the remaining test models and photos of the Beacon and the Echo. By the time I need a place to install it, hopefully the art world will have caught up/on. Which is a long way of saying I won’t be at Frieze this week.

online: , Ch. 6: The Odyssey of Project Echo, SPACEFLIGHT REVOLUTION by James R. Hansen [history.nasa.gov]

not online: A Minor History of Giant Spheres, by Joshua Foer [cabinetmagazine #27]

The Inflatable Satellite [americanheritage.com]

Previously: Dugway Proving Grounds, the world’s awesomest earth art?