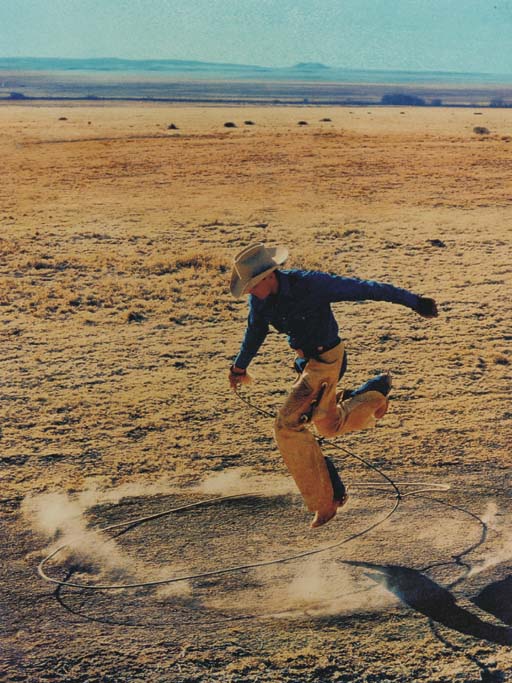

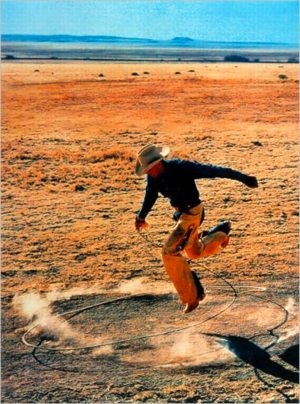

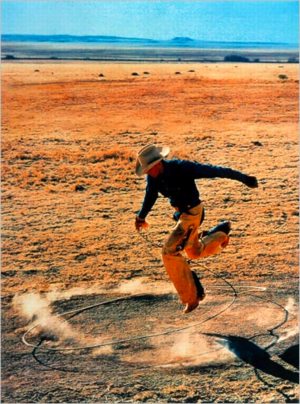

So the other day, I was still trying to wrap my head around the fact that Slate’s editors were, “ironically, unable to get permission” to reproduce Richard Prince’s Untitled (Cowboy), 2003 for Sarah Boxer’s slideshow review of “Into The Sunset,” MoMA’s exhibition of photography’s role in creating the concept of the American West. [The irony, of course, is that Prince’s work is actually a rephotograph of a Marlboro Man ad, which was probably photographed originally by Jim Krantz.] [Update: actually, last year, PDN identified the original photographer as Sam Abell. thanks Joerg.]

And so I blithely grabbed an image of Untitled (Cowboy) online, resized and retitled it, and republished it as my own work, 300 x 404, After Untitled (Cowboy) 2003 by Richard Prince, and offered to let Slate show it instead. Though I’ve written for Slate before, they have not, as yet, taken me up on my offer.

Not that I expect them to. The point that Slate felt copyright-constrained while Prince so clearly didn’t was so obvious, it’s barely interesting. And even their complete abrogation of fair use principles, which specifically allow reproduction of copyrighted work for purposes including “criticism, comment, [and] news reporting,” is kind of equivocal.

Boxer’s piece was decidedly not a review, and it could arguably not be news, but I can’t see how Slate could decide it wasn’t comment. I have to assume they just accepted some publicist’s refusal–whether MoMA’s or Prince’s dealer Barbara Gladstone [at the time the work was made, anyway. Now it’s Gagosian.] they don’t say–to provide a suitably hi-res file. If they’d wanted to run the image, they could have grabbed a slightly smallish version online, or they could have scanned Prince’s work from the catalogue, but they acquiesced to the wishes of someone somewhere who, ironically, did not actually control the copyright anyway. Fine, now we know.

After posting my one-liner, though, I started thinking more about this work I’d just created, what claim I really had to it, and what relationship it really had vis a vis Prince’s–and Krantz’s Abell’s–work. The pixel count in the title seemed to hold a key. A relatively new articulation of fair use exemptions has emerged specifically to deal with the no-permission-necessary reproduction of images online. Though it didn’t offer any technical guidelines, a 2002 lawsuit, Kelly v Arriba Soft Corporation, helped establish a fair use exemption for thumbnail images.

And that’s what interests me most about my re-reproduction. What’s a thumbnail? What size and quality does an image have to be to qualify for online fair use? What does its thumbnail-ness relate to? The size of the screen? Of the page? Of the original? Does it relate to the resolution, or just the display size? It’s an issue I think about every time I grab someone else’s image and post about it here. Beyond just giving credit and a link, I try not to create a perfect substitute for someone’s original, or for the context they put it in. [Ironically-again, that word–when I started greg.org way back in 2001, I was still a little hippie dippie Xanadu-ey about it all, and would hotlink to too many images. Too many of those impolite, dead links are still lurking in my archives, waiting for my ghost army of interns to fix.]

And what happens when you start reproducing a work that begins online and is defined first and foremost, not by its resolution, but by its pixel count?

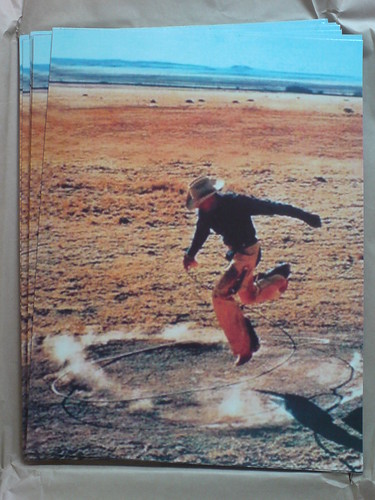

When I started looking for a place to print 300 x 404 on canvas, I found that it wasn’t so easy. The original web resolution, 72 dpi, would only produce a tiny, 4×5-in painting. I wanted to see something, you know, more Princeian, a 30 x 40-in. painting [10 ppi] or maybe even a Gurky-esque 60 x 80-in. [5 ppi], 60 inches being the maximum width of canvas today’s printers can handle.

As any Photoshop user can tell, increasing the pixel size is like zooming in on a digital image. Except in this case, it’s not the size of the magnifying glass, but the size of the pixel itself that increases. And since it’s the pixel count, not the size that’s important, I figured I’d go with a round number, 1 px = 1 mm, or 25.4 ppi, which would produce a nice, manageable little 12 x 16.2 painting.

Or at least it should. According to all the print studios I’ve spoken to, you can’t adjust the print resolution on their state-of-the-art inkjet printers; you can only get “the best” resolution. And if your image isn’t hi-res enough, no problem; they’ll fix it for you:

We understand that almost no one has a digital camera capable of producing native resolution for a 30X40 giclee at 150ppi. We can use image interpolation to compensate.

For example, if ordering a 30X40″ print, we would generally require to have a file that measures 30X40″ at 200 ppi.

Digital cameras compete on megapixel counts, and generations of printers claim they can [finally!] be “true” to an original work of art. And when an original doesn’t hold up, “image interpolation” comes to the rescue. The assumptions of accuracy, authenticity, and fidelity are embedded deep in our image-saturated world. And just as HD television forced the development of new makeup techniques to save large-pored actresses’ careers, our own perception of veracity is constantly changing in ways we don’t acknowledge.

Now consider Sarah Boxer’s assessment of Prince on Slate which is, at every level, incorrect:

Although the photo looks authentic, it is, at every level, inauthentic…Prince didn’t really take the picture of the cowboy himself. And even the original photographer wasn’t catching a real moment in a cowboy’s life; he was just shooting an ad.

That “just shooting an ad” kills me. Has there ever been an ad campaign more relentless in its pursuit of visual and content authenticity than Marlboro’s? Is the photo “inauthentic” because it’s an ad? Because it’s not a “documentary”? Is the cowboy inauthentic only if he is auditioned, dressed, placed or directed? Isn’t Prince’s photograph of the photograph a near-perfect 1:1 representation? Prince’s work provokes these kinds of questions and challenges these kinds of assumptions, the very ones Boxer seems completely oblivious to.

But I can’t laugh too hard; as my little offhand attempt to accurately reproduce my 121,200 pixels is proving, I’m just as likely to be oblivious to the limits of my own assumptions, too.