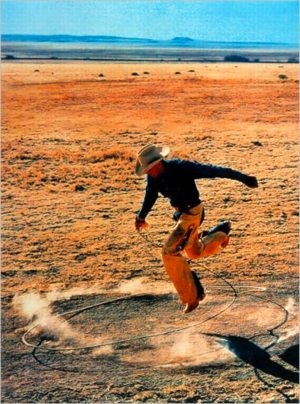

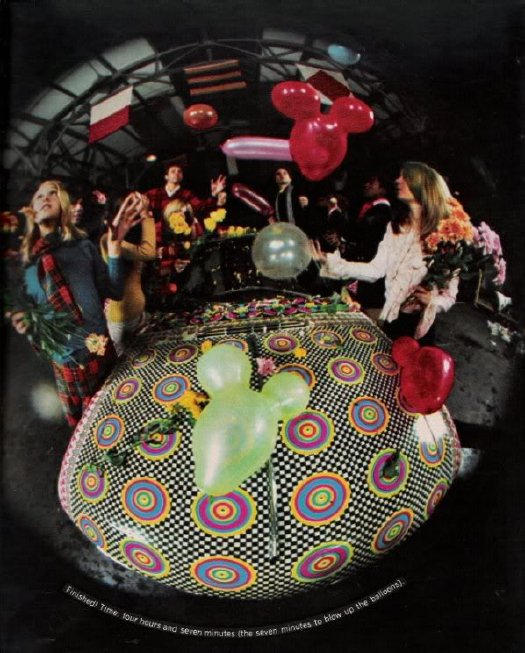

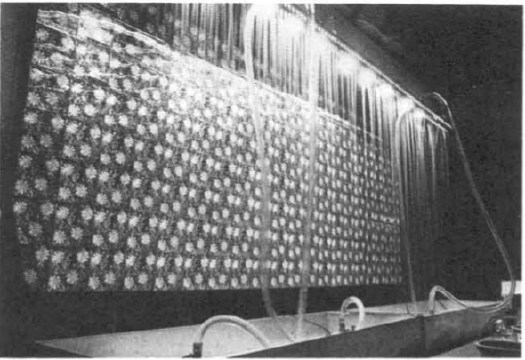

First up, a high five to Andrew Russeth at ArtInfo for highlighting Nicholas Robinson Gallery's summer installation of Andy Warhol's unusual Rain Machine (Daisy Waterfall). What a weird, wonderful--but mostly weird--work.

It's basically a mural of shimmering, lenticular photos of flowers behind an illuminated, recirculating, double wall of simulated rain. Let's set aside the fact that the raw mechanicality of Rain Machine makes it look like a missing Pop link in the genealogy of Olafur Eliasson's work. The similarities are both less and more interesting than they first appear.

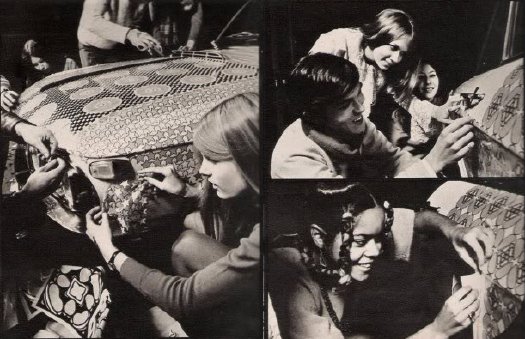

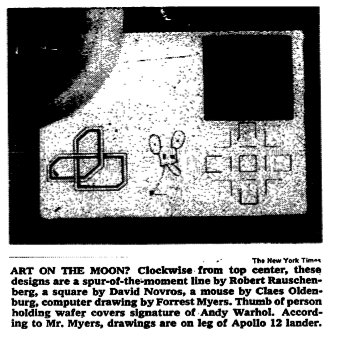

Begun in 1968, Rain Machine has its origins in two of my favorite pseudo-utopian art/technology events, the Osaka 70 World Expo and LACMA's sprawling Art & Technology collaboration project, which ran through 1971.

When Warhol was first approached for the A&T Program, which paired artists with cutting edge technology companies to realize a new, innovative work of some kind, he imagined making a wall of 3D holograms that would be barely visible through the mist. But Bruce Nauman had already nabbed RCA's hologram guy, so Warhol fell back onto decidedly low-tech lenticular imaging.

Then the rain wasn't working, the prints didn't line up, the budget was a joke, the US Pavilion exhibition space was cramped, the whole thing was a potential mess. The story is recounted in glorious, play-by-play detail in LACMA's 1971 Art & Technology Report, which is cheap to buy used, and [brilliantly] available as a free PDF download from LACMA's online library:

Perhaps the most important decisions determining the work's final appearance in the U.S. Pavilion at Expo were made not by Warhol but my MT [Maurice Tuchman, LACMA's A&T curator/organizer], the Expo Design Team members, and some of the other artists in the show. The entire installation operation was characterized by a sense of crisis, and there were moments when the peice seemed simply destined to ignominious failure. In the end, somehow, it worked; many people and particularly the artists who were there installing their own pieces, felt the Warhol to be one of the most compelling works in the exhibition because of its strangely tough and eccentric quality. Robert Whitman commented that "of course Andy's forcing everyone into the act;" the work istelf, when completed, made that conspicuously evident, and yet it was unmistakably Warhol. When it was rumored at one point just before the opening of Expo that the work might be taken out of the show, as was suggested by several of the Expo Designers and by a visiting critic who was conversant with Warhol's oeuvre, the American artists who by this time knew the piece intimately objected strenuously.When Rain Machine came back to LA, it had to be reworked, or debugged, and reconfigured. The most noticeable change is probably the scaled up daisy photos. As Robinson explains, the current installation follows an even newer [remastered?] set of specs developed by the Warhol Museum for its 2002 refabrication of the work.

Update: Interesting, LACMA received a set of nine lenticular daisy photos as a gift in 1999. They're the larger, single daisy-style, which makes me think they were extras, loosies, or maybe even leftovers from the 1971 Art & Technology reinstallation. A few of these have popped up in the market over the years; they're not that expensive, though without the rain--hell, even with the rain--they're a little weird.

Update Update: aha, interesting. according to this auction description, the lenticular photos were commissioned in an edition of 50 for the LACMA show.