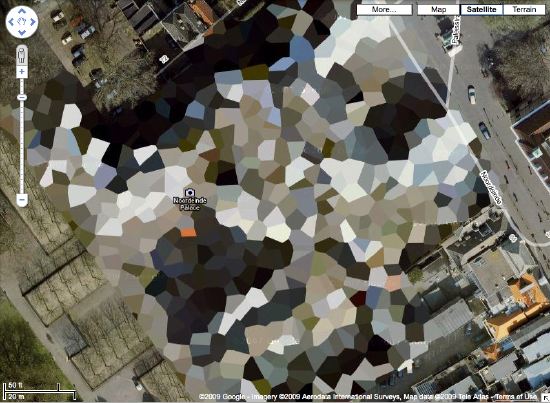

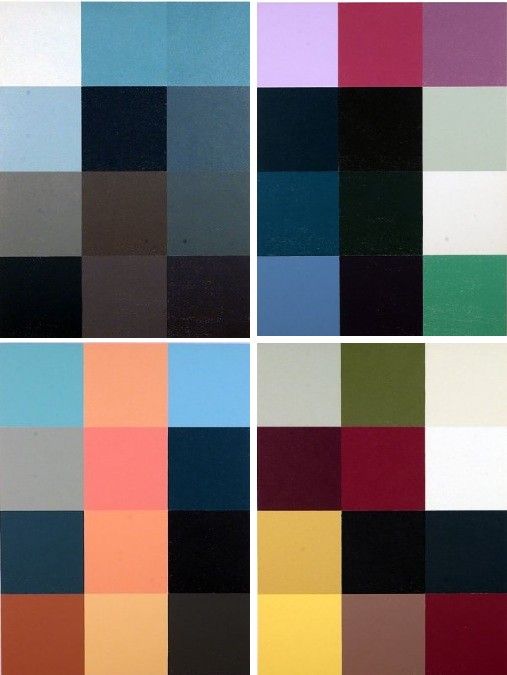

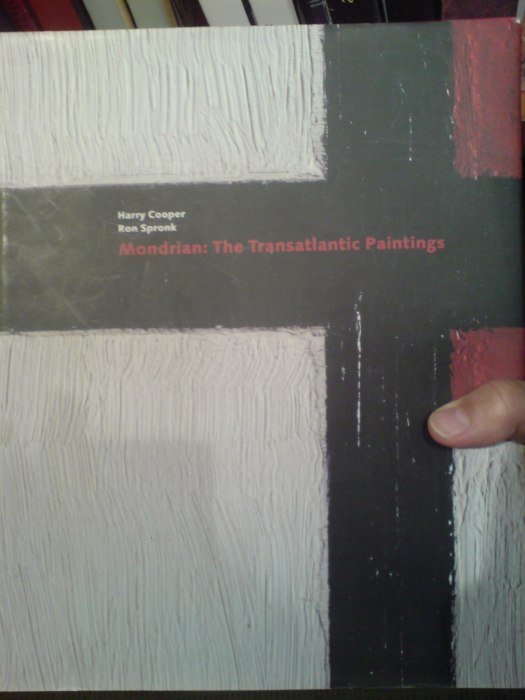

Holy smokes, it's been 15 months since I found the Dutch Camo Landscapes on Google Maps; just over a year since I started systematically screengrabbing them; a little less than a year since Google's particularly beautiful Delaunay triangulation distortion was replaced by a more typical pixelation algorithm; and about the same time since I last posted one of the "What I Looked At" installments, where I tried to figure out how to approach painting these things by studying the techniques of other hybrid, found, hard-edge, geometric digital, photographic, reductivist, surveillant, abstract, or Dutch Landscapes. Folks from Albert Cuyp and Picabia to Arthur Dove and Sheeler to Mondrian to Sherrie Levine [below].

The longer I take to think about how to paint without actually trying to paint, the more I keep accumulating and questioning potentially resonant work. And I wonder: what would it mean to consciously appropriate someone else's technique? if I taped my edges, would there be more of a connection to Odili Donald Odita? If I made little polygonal stencils and squeegeed, would it be too Brillo? Is there an implication in the kind of precise painterly edges of Mondrian as opposed to the surprisingly tentative edges of Sheeler, or the just-fill-it-in forms of Dove? Should I skip the paint, and just blow those bad boys up and print the hell out of'em on the biggest canvas/paper I can find?

It [basically, obviously] boils down to some ongoing uncertainty or doubt or skepticism or insecurity or whatever over whether these things should exist. Emphasis on things and should. Does everyone who makes stuff feel that? It's like Baldessari's classic fortune cookie of a painting, "I will not make any more boring art," but with the make in flux as much as the boring. I just remained unconvinced about the justification for these images as objects. [On the "bright" side, like the unshot film in the director's mind, the unmade artwork does remain perfect--for me, anyway.]

Anyway, all this comes to the fore because last summer, I saw images of some polygonal abstracted landscape paintings by Douglas Coupland, which were part of, or inspiration for, or somehow connected to, the Fall/Winter clothing and home furnishings colabo he designed for the Canadian retailer Roots. They were exhibited and for sale in Coupland X Roots pop-up stores in Vancouver and Toronto.

There was zero info online, so last summer and fall, but I deduced that they were digital reductions of iconic paintings by the Group of Seven, the early 20th century landscape painters who rather self-consciously set out to create a national cultural and visual identity for Canada via its landscape. Coupland's Roots collection was an extension of that national branding project, only he referenced the unifying forces of electrification, television, and moose logos.

At least that's what I gleaned from the web and press releases. I tried in vain to get any information on the paintings from Roots, Coupland, or his galleries, but it was total radio silence. So I ignored them back. Only now, as I check back, do I find that "culture guru" Coupland has a show up of the paintings, through this week, at Monte Clark Gallery in Vancouver. Faux-encrypically titled G72K10, the paintings turn out to be exactly what I thought they were.

"Thomson (Sunset), 2010, Oil on canvas, 58 x 72 inches" image: monteclarkgallery.com

To a point. Because though the captions say things like "oil on canvas" and "acrylic and latex" and "unique pigment print" it is completely unclear whether the images on the dealer's website are of the objects themselves or of their digital sources. Maybe it doesn't matter to Coupland. Here's how the gallery describes them:

By digitizing the likeness of specific works, Coupland has produced large-scale hard-edged paintings on canvas, presenting his own vision of the Group of Seven in 2010.Doesn't sound like he'd use something as retardataire as a paintbrush for a forward-looking project like that. Though it's hard to tell from the jpg, the date on this unidentified type of limited edition print being auctioned next month by the Writers' Trust looks earlier than 2010. Or not.

So while I still can't decide if my painterly obsession is a vice, Coupland's project is at least makes clear that materialist indifference in the pursuit of digitized aestheticism and conceptual slickness is no virtue.