You know what, it's the weekend. We can have two long Leo Steinberg-related posts at once. Read'em on the NetJets to Basel.

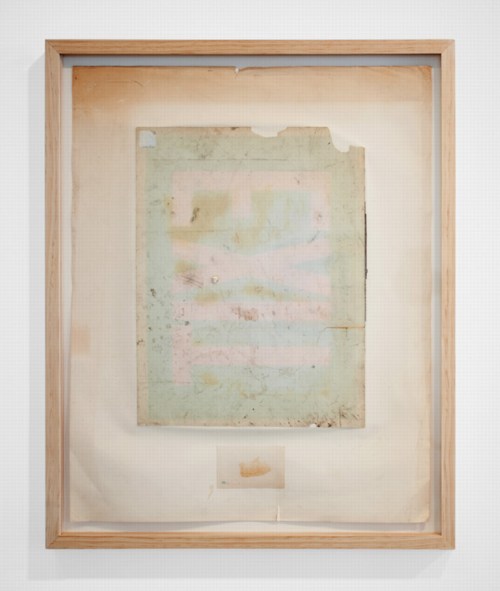

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it's not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote "Other Criteria."

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it's not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote "Other Criteria."

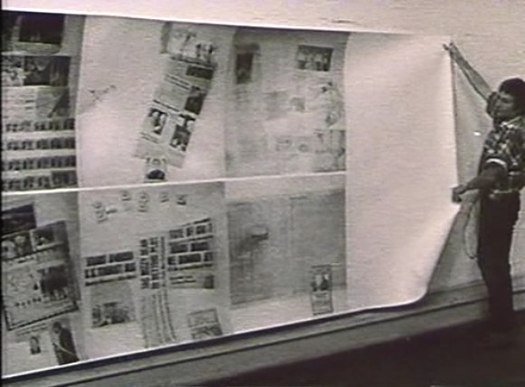

And as he tells the story in his awesome 2000 book, Encounters With Rauschenberg - A Lavishly Illustrated Lecture, Steinberg makes not seeing it the point. I'm really tempted to include all seven pages of EdKD from the 85-page book--the text was published straight from his lectures for the 1997-8 Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim and Menil, and it really sounds just like him. [I met Steinberg in 1991 when the delightfully friendly woman I was sitting next to for his Picasso lecture series at Rice University introduced us; she turned out to be his host, Dominique de Menil. Life-changing, &c, &c. but not right now.]

But I won't. Even though it's out of print and expensive. It really should be a PDF now. Anyway.

Steinberg's take on EdKD is useful here because he was watching Rauschenberg's career and involved in its critical dialogue almost from the very beginning; he's about as well-informed or as thoughtful an audience voice as Rauschenberg could find in the 1950s and 60s. And so his reaction seems like a good proxy for the best perspective possible of the time. And it sounds like, though he felt he had to address it, and though he could argue for its critical or conceptual significance, Steinberg didn't really like Erased de Kooning Drawing very much. It bugged him. He even apologized to his lecture audience for spending "so much time on a negative entity" and a "one-time exploit." But but!

The lead-in for his story about first encountering EdKD was, interestingly enough, an anecdote from 1961 and Rauschenberg and Johns, about artists putting personal content into their work, and denying it, and then eventually 'fessing up, and so about not quite trusting what artists themselves said:

That experience confirmed me in a guiding principle of critical conduct: "If you want the truth about a work of art, be sure always to get your data from the horse's mouth, bearing in mind that the artist is the one selling the horse."

And did I abide by my principle? I should say not! My longest conversation with Rauschenberg occurred c. 1957, when I first heard about something outrageous he'd done some years before. And rather than going after the outrage--the horse, as it were--I called the trader.

[uh, don't want to spoil the story arc, but isn't not ignoring a lesson in 1957 that stems from looking back from the 80s to a 1961 conversation putting the horse before the trader? Just sayin'. -ed.]

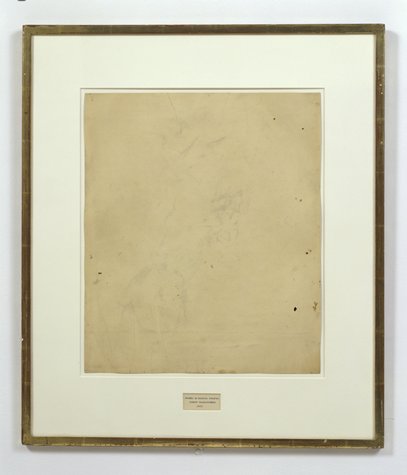

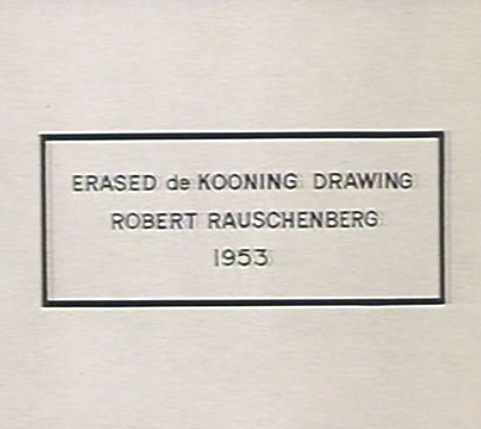

The work in question was Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953. The piece had not been exhibited; you heard of it by word of mouth. I did, and it gave me no peace. Because the destruction of works of art terrifies.

See, now this is news right there: not exhibited before, word of mouth, a piece you know and worry about without seeing.

How could Bob have done it; and why? The work is often, and to this day, referred to as "a Neo-Dada gesture," but that's just a way of casting it from your thought. Obvious alternatives to Neo-Dada suggested themselves at once. An Oedipal gesture? Young Rauschenberg killing the father figure? Well, maybe.

But wasn't it also a taunting of the art market?--an artist's mockery of the values now driving the commerce in modern art?

This would put paid, so to speak, to Norman Mailer's complaint that Bob was erasing to play the market. Steinberg tells how everyone was very aware/shocked/jealous/disturbed when a de Kooning finally sold for $10,000. And Rauschenberg was the one, don't forget, who got the angriest at Robert Scull for his market-making auction some years later. But all these seemingly contradictory interpretations, Steinberg pointed out, were just assumptions from afar.

So I picked up the phone and called the horse trader himself. And we talked for well over an hour. Occasionally, thereafter, I considered writing up what I remembered of our talk, but then Calvin Tomkins discussed the Erased de Kooning Drawing in his Rauschenberg profile in The New Yorker, and he did it so well that I thought, "Good, that's one less thing I have to write." But I don't mind talking about it and recalling whatever I can of that phone conversation.

On the first question of why, Rauschenberg gave an explanation similar to the one he'd told Emile de Antonio: he was interested in drawing with an eraser "as a graphic, or anti-graphic element," and found that erasing his own work was unsatisfying.

As for why de Kooning and not some other pre-existing work of art, Steinberg examines and largely discounts the Oedipal explanation, and instead suggests that Rauschenberg recognized or claimed a kindred spirit, that erasure as a technique was central to de Kooning's own practice. And yes, this section I'm obviously going to quote at length:

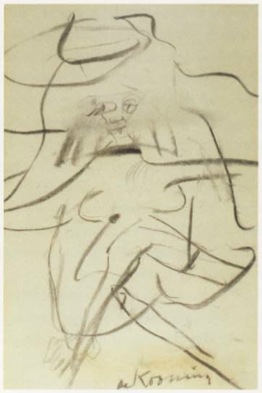

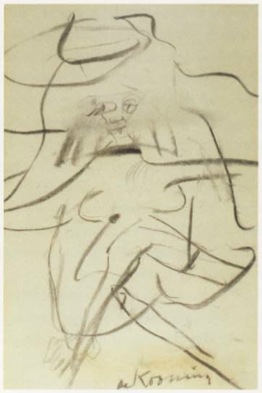

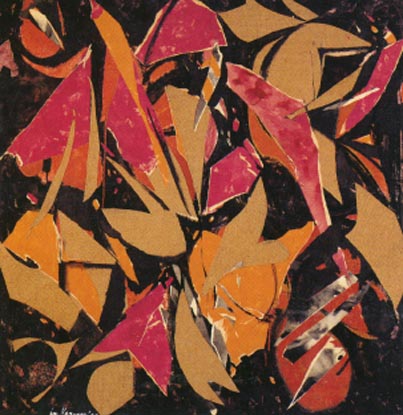

There is another reason, I think, why Bob lit on de Kooning. I live with a de Kooning drawing from the early 1950s--it's of a seated woman, frontal, legs crossed [below]. The face was drawn, then erased to leave a wide, gray, atmospheric smudge; and then drawn again.

Willem de Kooning, Woman in a Rowboat, 1953

And here is Tom Hess' account of Bill de Kooning's working method. I'd like to read you a paragraph from Tom's book Willem de Kooning Drawings (1972), and I'm encouraged to do this by the example of Rauschenberg's Short Circuit combine, which, you remember, brought in some of Bob's friends piggyback. Tom Hess was a friend; hear him describe de Kooning's habit of draftsmanship.

I remember watching de Kooning begin a drawing, in 1951, sitting idly by a window, the pad on his knee.He used an ordinary pencil, the point sharpened with a knife to expose the maximum of lead but still strong enough to withstand pressure. He made a few strokes, then almost instinctively, it seemed to me, turned the pencil around and began to go over the graphite marks with the eraser. Not to rubout the lines, but to move them, push them across the paper, turn them into planes...De Kooning's line--the essence of drawing--is always under attack. It is smeared across the paper, pushed into widening shapes, kept away from the expression of an edge...the mutually exclusive concepts of line and plane are held in tension. It is the characteristic open de Kooning situation...in which thesis and antithesis are both pushed to their fullest statement, and then allowed to exist together...

This much Tom Hess.

In view of such working procedure, one might toy with this further reason why Rauschenberg's partner in the affair had to be de Kooning, rather than Rembrandt or Andrew Wyeth. De Kooning was the one who belabored his drawings with an eraser. Bob was proposing a sort of collaboration, offering--without having to draw like the master--to supply the finishing touch (read coup de grace)

I could just go on and on. Steinberg noticed that, despite declaring his early love for drawing, Rauschenberg seems to have pretty much stopped drawing after the early 50s,

Erased de Kooning Drawing was really about erasing drawing itself.

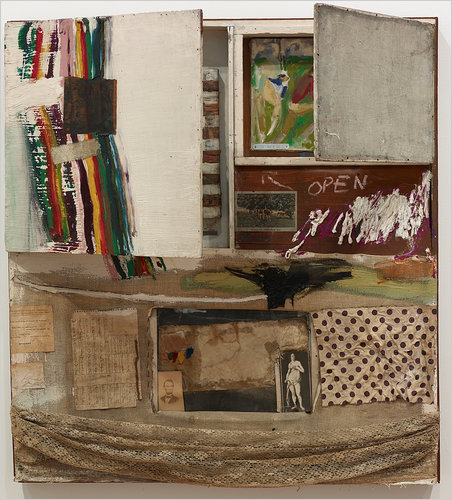

And since he brought it up, and in the context of collaboration, too, maybe that makes Short Circuit, which includes two paintings by his partner and ex-wife, a way to wrangle painting into its place, too: subsumed behind closed doors. It's an admittedly rough analogy, but then, I only just thought of it.

In any case, Steinberg's collaborative interpretation of Erased de Kooning Drawing is worth holding onto. On with the story:

Meanwhile, Bob and I are still on the phone. And Bob says, "This thing really works on you, doesn't it?"...Finally, I asked, "Look, we've now been talking about this thing for over an hour, and I haven't even seen it. Would it make any difference if I did?" He said, "Probably not." And that's when it dawned on me--it's easy-come now, but the thought had its freshness once--I suddenly understood that the fruit of an artist's work need not be an object. It could be an action, something once done, but so unforgettably done, that it's never done with--a satellite orbiting in your consciousness, like the perfect crime or a beau geste.

Since then, I've seen the Erased de Kooning Drawing several times, and find it ever less interesting to look at. But the decision behind it never ceases to fascinate and expand.

It now seems to me that Rauschenberg has repaid de Kooning's gift to him. For though we all know de Kooning to have been a great draftsman, I can think of no single de Kooning drawing that is famous the way some of his paintings are, except the one Bob erased.

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it's not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote "Other Criteria."

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it's not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote "Other Criteria."