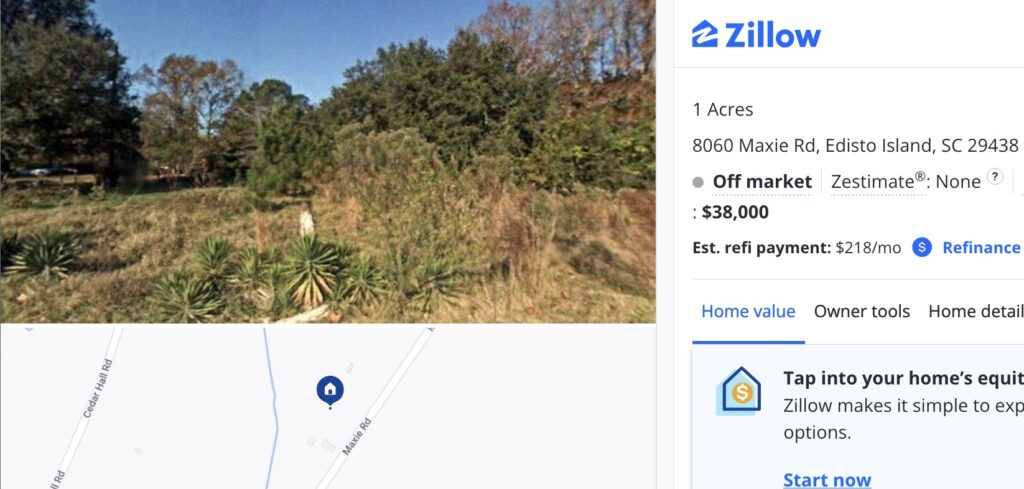

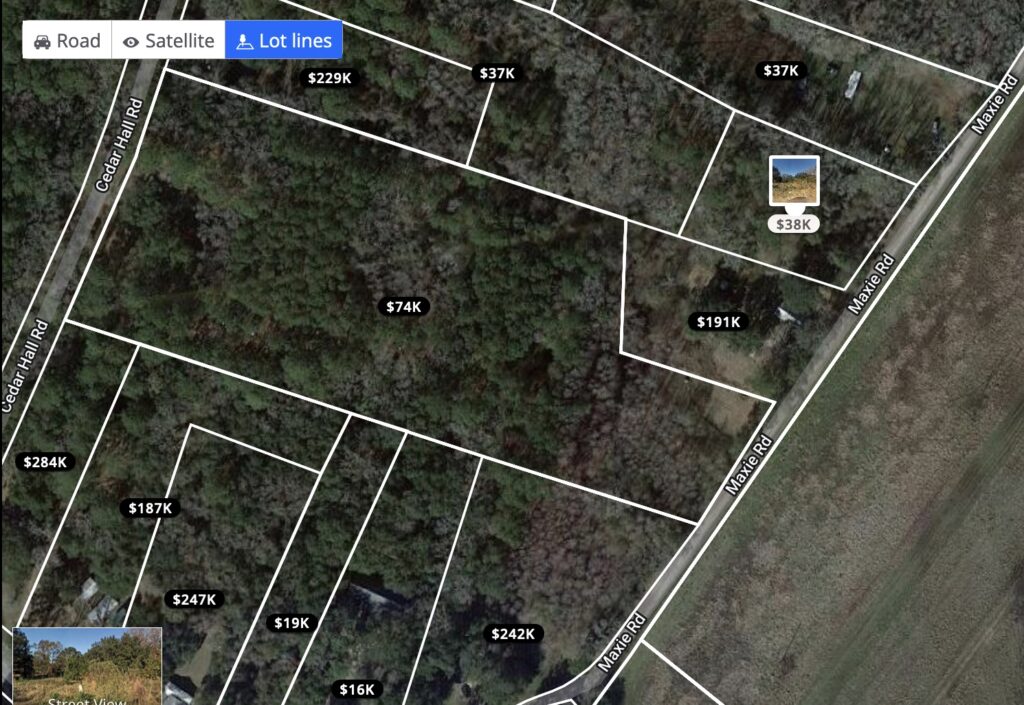

Until 2018 Edisto Island meant one thing in the contemporary art world. Then after, it meant another. Or rather, it meant two things. On August 6, 2018, Cameron Rowland bought an acre of land that had once been part of an enslaver’s plantation; then was part of a “forty acres and a mule” Freedmen’s reparations order; and then was almost immediately repossessed by the former enslavers. Rowland bought the land and placed restrictive covenants on its deed that remove any use or monetary value. The land and the deed constitute their work, Depreciation, and Dia just announced stewardship of it.

The work comprises the land and the deed, but that is not all. Depreciation is owned by 8060 Maxie Rd, Inc., a not-for-profit corporation Rowland established to execute the work. The company is named after the land’s address on a road named after the enslavers. Rowland maintains the corporation, and thus ownership of the work, and has put it on extended loan with Dia.

This is an almost perfect corollary to other site-specific works affiliated with Dia. Spiral Jetty, for example, was donated to Dia by Robert Smithson’s widow Nancy Holt, but the estate retains intellectual property rights. And the work, importantly, sits on lakebed, leased from the State of Utah. [In 2011, when Dia seemed to be neglecting care of Spiral Jetty, and let the lease expire, I created The Jetty Foundation to bid on it and bring local institutions and stakeholders into stewardship. The State incorporated the terms The Jetty Foundation proposed in its bid into Dia’s renewed lease. Things got better after that—and Dia’s leadership change. And now look at them.]

Depreciation differs from Dia’s other sited works, in that “8060 Maxie Road is not for visitation.” As the press announcement states, “The legal status of the land is the crux of the artwork. The framed documents that survey the land, register its purchase, and define its legal status make up the component of the artwork that is intended for exhibition. The experience of the work is not predicated on visiting the land and, in fact, visitation is discouraged.”

I’ll bet. It’s not just that art pilgrimage represents a potential source of economic value that might inhere to even a useless, worthless site that has been incorporated, if not transformed, into a work of art. Though this is certainly a parameter that exists beyond the elements Rowland designates for the work. The land itself still exists in a contested community; it’s not like the injustices of racialized slavery and antagonism over control of land in South Carolina are only a 19th century artifact. Is Edisto a sundown town for challengers of the regime of property? What *do* Edisto residents think of Depreciation? We pointedly do not know. But I totally get it if Rowland and Dia don’t want to have to have that conversation because caravans of art-glomming influencers on their way to Art Basel start doing TikTok dances on conceptually reparated Freedmen’s land.

Speaking of Edisto residents, we really don’t, do we? I haven’t seen even the slightest reference to him, and I trust Rowland’s meticulously researched and presented texts for their work—I’m frankly in awe of them as some of the most lucid and powerful writing I’ve ever seen. But their research and awareness means there is no way Rowland didn’t know and at least consider the connection Edisto Island has to Jasper Johns. Clearly Depreciation is not about him, or his omission. But it does make me think about Johns as a South Carolina artist, a white man with a history in this place, both his family’s and his own—Johns moved to Edisto in 1961 after his messy breakup with Robert Rauschenberg, and stayed there until his house and studio burned down in 1966. It makes me notice how removed from the contestations of race and the privileges of whiteness he and his work have been since, well, since his whole career. Maybe Deborah Solomon’s biography of Johns will shed some light on these issues, if not light a fire under them. But that is literally another blog post.

Rowland’s destabilizing power is even more fascinating to consider in the context of another of Dia’s sited works: Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field. De Maria constructed Lightning Field on homesteaded land which had been parceled out by the US Government in 160 acre tracts beginning with Union veterans of the Civil War. The size of homesteads eventually grew to 640 acres. Lightning Field‘s original site and cabin are the product of this early 20th century homesteading initiative, but Dia has also gone to great expense to buy thousands of additional acres in the “viewshed” of Lightning Field, creating a visual buffer, wild by control, to preserve the artist’s intended experience of the work. Vistor access is highly restricted, and photos are discouraged. Dia owns the copyright to the nine photographs of the work approved for publication. Rowland’s Depreciation sticks another pin in Lightning Field, lighting up the status of its unceded, contested, securitized, privatized, and aestheticized site.

But then, I guess Dia already knows that. “[A]s a site that questions notions of property, land occupation, and the art pilgrimage, Depreciation both complements and productively challenges Dia’s existing sites,” said two Dia curators, Jordan Carter and Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, somehow. “In this context, it critically shifts Land art’s terms of engagement and proposes new urgencies, stakes, and possibilities within the institution and the field.”

Maybe someday visitors to Lightning Field will open the info binder in the cabin, and find, in place of a pro forma land acknowledgment, Rowland has inserted a work that subsumes de Maria’s work whole—and the Dia with it. And the challenge is so powerful you’re left wondering if you still even have a ride back to town.

Visit Our Locations & Sites [BUT NOT THIS ONE] > Cameron Rowland, Depreciation, 2018 [diaart.org]

Previously, related:

2022: Not Standing For It

2020: Affairs of State

2018: Please do not sit on the Art Furniture

2015: Lightning Field Notes

2011: Site Specifics: Why I’m bidding on the lease for the Spiral Jetty site