Call it Team ANTI-America, just the kind of devious attack you’d expect in an election year: The ever-patriotic MPAA is bravely taking a stand, seeking to protect the high-quality of simulated puppet sex [SPS] America’s children know and love from cheap Hollywood imitations.

For the last year or so, the Broadway musical, Avenue Q, has been offering Tony Award-winning SPS to Americas children for $95 a ticket. But now, a devious team of low-rent Hollywood types is seeking to flood the SPS market with a poorly articulated product available everywhere–not just on Broadway–for only $9.50, a shocking 90% discount.

The culprit: Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s ironically named Team America World Police, which is due in theaters next week. MPAA censors have been selflessly “studying” Team America‘s simulated puppet oral sex scene–nine times so far–to certify it’s good enough for kids. So far, the movie’s SPS has only received an NC-17.

Note: the MPAA only certifies the quality of SPS; all other puppet simulations are currently unregulated and available on basic cable.

Puppet oral sex goes against grain for US censors [Guardian, LAT, via boingboing]

Author: greg

Village Voice: It’s The Split Screen, Stupid

Even the weekly, leftwing, activist, downtown media (owned by a religious conservative, suburban billionaire) said the George Bush media masterminds flubbed the debate last week.

Late to close, but still wanting to kick the man when he’s down, the Village Voice’s James Ridgeway discusses gloats how the split screen–which captured Bush’s antsy reaction shots for all the world to see–tipped the outcome of the debate.

See Bush Twitch! [Village Voice]

Mexican Consolidated Drilling Authority

That’s one suggested translation of “La Mexicaine de Perforation,” the amorphous group of urban explorers who built and operated a subterranean cinema in the center of Paris until it was discovered last month.

The group’s spokesman, Lazar Kunsman, originally explained the name in a French radio interview, but early English language reports of the movie theater botched both the original and the translation, and I unwittingly perpetuated their mistakes. La Mexicaine de la Perforation [sic] became The Perforating Mexicans [sic sic], which is what happens when British people think they speak French.

Le Mexico is the bar where the explorers would meet, and perforation is drilling, as in mining and quarrying. According to Language Log, the name shares its construction with industrial, utility, and institutional names in France.

This is all fascinating, I’m sure, but it’s not nearly as interesting as what films LMDP screened during its summer-long film series, Urbex Movie. I’m still working on that. [Thanks, Tristan, for the correction]

Related: Language Log deciphers “LMDP”

Hey, You See How Well It Worked In Iraq…

Talking about his daughters last night, George W. Bush said he’s “trying to put a leash on’em.”

U Miami Transcript of Bush/Kerry debate [PRNewswire]

So What, It’s Rewritten? So Let It Be Sung!

At last, the Hebrews have hearkened unto that voice in the wilderness, that great prophet who came down off the mountain.

At last, the Hebrews have hearkened unto that voice in the wilderness, that great prophet who came down off the mountain.

Translation for the godless: The Times has a review of Ten Commandments: The Musical (“Val Kilmer IS Moses.”), which Defamer has been preaching about for days.

Figuring that Christian audiences are well known for embracing wild-ass reinterpretations of biblical texts [??], the producers of TC:TM VKIM went ahead and rewrote The Commandments: “‘Thou shalt not steal’ becomes the considerably less pithy ‘Don’t take things that belong to someone else.’ There’s also the interestingly ambiguous ‘Never lie about others.'”

Here, for your salvation in the Promised Land, are all ten of Val Kilmer Is Moses’s Ten Commandments, as revealed to me this morning while I was burning through a bushel of Crunchberries:

| God says | Val Kilmer IS Moses says |

| Thou shalt have no other gods before me. | What part of “Do you know who I Am?” don’t you understand? |

| Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image. | “the taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly prohibited [in the Kodak Theatre].” |

| Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain. | Step 1: Instead of ass say buns, like “kiss my buns” or “you’re a buns hole” |

| Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. | No, I will not use a Crackberry. |

| Honour thy father and thy mother. | Dick Grayson : You can’t understand. Your family wasn’t killed by a maniac. Bruce Wayne : Yes, they were. |

| Thou shalt not kill. | ibid. |

| Thou shalt not commit adultery. | Inexplicably dropped from the original French production. US production: Sorry, no kissing. |

| Thou shalt not steal. | Don’t take things that belong to someone else. |

| Thou shalt not bear false witness. | Never lie about others. |

| Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, &c. | “rules for the press line: DO NOT ASK ‘Who are you wearing?’ |

He Sings, He Dances, He Parts the Red Sea [Charles Isherwood, NYT]

The Ten Commandments: Val Kilmer up to his old tricks [Defamer]

The Sound of One Hand Clapping Over Your Mouth

It is about this time that we realized we were in a room of fundamentalist film students, for they were laughing appreciatively with the person in the position to one day give them work, and sneering at the representative of a free press. In short, they are fully prepared for Hollywood.

– bwahahaha, Fox Searchlight gets all Rathered up, planting (aka “inviting”) a NYT’s gossip reporter [sic] in a Columbia U. screening and Q&A where my boy, David O. Russell, worked the crowd into a frenzy against her by criticizing Sharon Waxman’s leg-humping I Heart Huckabees article.

Hey Pal, Where’s the Lousy Compassion? [Boldface Names, NYT]

The Nudist Buddhist &c., &c. [greg.org]

Hints of the New Museum of Modern Art

In the last two days, I’ve heard two curators from MoMA talk extensively about what the new building and the reinstallation of the art in it will be like. To use the phrase of the evening, I’ve gotten mixed signals.

Terry Riley discussed Yoshio Taniguchi’s building as the next major datapoint in the generations-long experiment of how architecture should address modern and contemporary art. In contrast to the Guggenheims, which engage art with their own influential, expressive intent, MoMA’s buildings–almost since its founding–has served as a “machine in the service of art,” emphasizing flexibility and utility.

After the powerful statement of Bilbao, Taniguchi’s MoMA, Riley said, “restabilizes” and reinvigorates this debate. And it does it with “logic” and “tradition,” some of the same principles contemporary artists worked against when making their art.

Nevertheless, Riley predicted people “will be shocked” by the vitality and dynamism these allegedly “conservative” principles bring.

On the art front, Ann Temkin, a curator from Painting & Sculpture, revealed that “Art History 101,” MoMA’s longstanding, authoritative chronological approach to displaying its renowned collection would return in November, albeit in expanded form. The thematic experiments of the MoMA2000 shows and the Tate Modern’s idea-driven installations seem to have reinforced the curators’ belief that MoMA’s uniquely deep and broad collection come with the unique responsibility to attempt to show this history. They’re doing it because they’re almost literally the only ones who can.

The “core historical collection” as taken in another generation, and art from the last 30+ years–which is still in process and historical flux–will be shown in consecutive 9-month views. Beyond these accretions and intentional change, the space, the vistas, the juxtapositions and potential paths generated by the new building are probably the greatest difference.

I’ve been in the almost completed building, and it is literally jaw-dropping. The atrium and the contemporary galleries are massive, and even the upper, historical galleries feel huge. MoMA’s got an unparalleled collection, sure, but I have to think that the building’s–the institution’s–new monumentality may end up overwhelming and subsuming many of the works we remember quite intimately. Some may even find it shocking.

Barely related: Not that anyone cares, but there’s some satisfaction in knowing that Charlie Finch got it almost 100% wrong.

Bloghdad.com/Remove_Your_Hairpiece

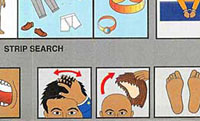

Kwikpoint specializes in visual language guides, laminated pictograph cards to help bridge language barriers in hospitals, foreign countries, in daily deaf life–and for law enforcement and the military.

Kwikpoint specializes in visual language guides, laminated pictograph cards to help bridge language barriers in hospitals, foreign countries, in daily deaf life–and for law enforcement and the military.

An Army captain with his boots on the ground calls their fold-out Iraq Visual Language Survival Guide “a hot commodity.” It includes point-and-don’t-shoot instructions for locating snipers, identifying the nationality of foreign terrorists, and, as pictured here, conducting a hairpiece-to-shoelaces strip search.

BoingBoing links to a couple of partial scans, but you can buy the whole thing for $11 directly from Kwikpoint. This is cooler than any deck of cards.

[via BoingBoing, Xeni, all is forgiven.]

‘Wong Kar Wai,” Cantonese for “When it rains,”

Wong Kar Wai Week continues. Remember that “interview” with Wong Kar Wai I just linked to? Turns out it’s the Access Hollywood Movie Minute version. The HBO Original Series version–long, convoluted, emotional tumult spread out over the whole thing, lots of special guest cameos, no easy plot wrapups–is in the New York Times Magazine. Titled “The Director’s Director,” Jaime Wolf doesn’t actually work many other directors into the story. Go figure.

I only mention this because Wong’s–and his last/family name is Wong, just so you don’t embarass yourself in print or conversation–films and career have a such deep, meaningful resonance with my own.

The Director’s Director [NYT Magazine]

The Making Of

That’s what I’m thinking of changing the subtitle of this weblog to, although I’m still unconvinced.

It works in Europe, where I am not, at least most of the time. Top ten lists on the radio are called “le best of,” as are McDo value meals (“menus best of”). Also, “the making of” has become a programming genre all its own.

But it still looks a little funny. And this ain’t Europe. And so I remain undecided.

FS: ‘Mission Accomplished’ Banner, Qty: One (1)

It’s hard to remember now, but things looked so different back then. In August. When Sharon Waxman put David O. Russell on the deck of an aircraft carrier the front page of the Times Arts section for “Conquer[ing] the Hollywood Studio System.” On Aug 16, Russell had turned Warner Bros. into his own personal Ahmed Chalabi, ready to do his bidding:

Well, that was the plan, anyway. To find out the truth, don’t bother reading the Times, who hasn’t covered the story since; slog instead through the foreign papers and crazy alternative journals like the Los Angeles Times.

Well, that was the plan, anyway. To find out the truth, don’t bother reading the Times, who hasn’t covered the story since; slog instead through the foreign papers and crazy alternative journals like the Los Angeles Times.Here’s a timeline of how, thanks to the foreign insurgents on the ground at Warners, David O. Russell’s grand Iraq strategy went terribly, horribly astray.

Continue reading “FS: ‘Mission Accomplished’ Banner, Qty: One (1)”

As Rumsfeld Is My Co-Producer

David Robb slogged through decades of data–a veritable quagmire of documentation, including production notes, official memos, filmmaker and producer interviews, and screenplay drafts–to write his new book, Operation Hollywood. From the interview he gave to Mother Jones, it sounds like a fascinating story.

That said, the interview gives me an odd feeling that the author–and maybe even Mother Jones herself–might be letting a strong political point of view slip through here and there. Nothing specific, though, maybe it’s just me.

I’m sure Operation Hollywood will become the must-read bible for anyone who decided to get into the motion picture business after seeing Top Gun [one hilarious anecdote from the book: enrollment actually shot up after Top Gun not in film schools, but in the Navy. Who’da thought?].

One wee bit of constructive criticism which I hope arrives in time for the paperback edition: In these perilous times, the book’s subtitle, How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies, seems needlessly divisive, by which I mean SATANICALLY UNAMERICAN. I suggest it be changed to How Hollywood Does Its Part To Help Keep The Pentagon’s Recruiting and Funding Pipelines Flowing, While Spending Some of That $500 Billion You’re About To Vote For In YOUR District, Congressman.

[via GreenCine]

Mother Jones Intern Intern-views David Robb

Support David Robb, the anti-Military Entertainment Complex, and buy Operation Hollywood: &c., &c. at Amazon.

Watch the Pentagon’s greatest cinematic success, Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line on DVD. [What? You say they didn’t do that one??]

Wong Kar Wai talks about 2046

2046 barely screened at Cannes, after the director hand-carried the not-quite-finished print to the rebooked theatre. Now it’s being released in the UK, and it turns out Wong has actually re-edited it since May.

Read Howard Feinstein’s interview with WKW and his recounting of the tortured making of in the Guardian

“It was like being in jail” [Guardian UK]

Related: I, too, delivered an unfinished film to Cannes, a fact I mention because of the deep, meaningful resonance between Wong Kar Wai’s films and career and my own.

Faster, Pussycat! Shill! Shill!

Do whatever it takes. Kill the whole friggin’ space program. Put NASA out of business; my wife can find another job. Bankrupt the entire airline industry, and ground every plane. I don’t care.

Just please, Xeni, please stop it with the PR pablum from some zero-G plane that last made the news during the shooting of Apollo 11. It wasn’t interesting when Howard, Hanks & Bacon blabbed on about it, either, but at least they stopped after the movie came out. Unless you’re going to ride a on-loan-from-Marketing Segway in a parabolic arc, get off the plane; the flight landed a long time ago.

“Previous BB posts: 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.” [BoingBoing: Xeni Flies Zero-G #10]

Eros, Thanatos, Thanatos, Eros: Russ Meyer RIP

Faster Pussycat, Kill! Kill! director Russ Meyer went tits up over the weekend; students of his rather buxom body of work will recognize his fondness for this position.

My greatest Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon triumph was connecting FPKK‘s Tura Satana to Kevin Bacon, via Herve Villechaise, which was possible only with the help of the then-little-known IMDb.com.

Russ Meyer’s Obituary, with nice quotes from fan John Waters & screenwriter Roger Ebert [LA Times]

Try it yourself: Faster, Pussycat! [IMDb]

Don’t mess with her copyrights. Seriously. [TuraSatana.com]