The bus moves slowly east, away from the galleries, cafés, and shops that have sprung up along the streets of Williamsburg’s north side, now a trendy artist and working-class enclave. Ten minutes into the quiet trip–there is no narration–a symphony of groans, clangs, and syncopated twitters, mixed live by two sound artists, issues from the back of the vehicle. The tour meanders past car-part lots, warehouses, and 24-hour delis to its promised land: blocks and blocks of waste-management treatment facilities serving New York City.

For four weekends this winter, the Dencity Bus Tour made its pilgrimages through the city’s trash and raw sewage. The ride, says Rene Gabri, one of the three artists who conceived and produced the tour, was meant “to interrogate the format of the tour itself, which relies on verbal information that is often incorrect anyway.” His collaborators, Erin McGonigle and Heimo Lattner, produced the live soundtrack, largely made up of samples taken from the industrial area itself.

According to Gabri, the tour evokes what wireless gadgetry promises to provide: “Moving through space, yet having a constant stream of information.” But all tours do that, or at least they try. Unique to Dencity is the detachment and illusory sense of privacy encouraged by the atmospheric music and darkness. On the bus that night, one couple made out, another gossiped, while others stared out the windows. Without the unifying element of a tour guide to produce a sense of community, Dencity has hit on, perhaps accidentally, a lonely vision of a supposedly hyperconnected world where each person has electronic access to all varieties of data, anytime, anywhere.

The Dencity bus tour and several other art expeditions have recently been making the metaphor of mobility material. Mobility as lifestyle has become ever more common in the past half-dozen years as portable electronic inventions allow us to roam further, with greater frequency, for both work and play. At the same time, global tourism has taken hold as a major wage-earning sector for some and a regular pastime for others. Nomad-themed art plays with these two dominants of contemporary life: the international, wireless culture of businesspersons, artists, entrepreneurs, and writers shuttling between Los Angeles, London, and Lagos; and the booming tourist culture that at times seems infected with a case of “scopophilia,” as Gabri puts it‹pleasure in looking, particularly at others.

The Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) in Culver City, CA, has also offered a series of on-the-road looks at waste-related scenery. The combination artists’ collective/rock-collecting club launched a self-guided tour in 1995 with their project “Suggested Photo Spot.” The “picture spot” was invented by Kodak, says CLUI director Matt Coolidge, “in order to put their logo up in national parks.” CLUI’s minimalist signs suggest tourists stop and notice more than the area’s inherent beauty.

The project planted 50 signs across the country, from the Trojan Recreation Area and Nuclear Power Plant in St. Helens, Oregon, to the Kodak Waste Water Treatment Plant in Rochester, New York, where CLUI’s sign informs visitors that “Kodak’s industrial waste water is treated at this plant in the beautiful Genesee River” and that “local lore has it that film can be developed in this water.” The satire offers pointed instructions to look beyond the “beautiful river” into its history within the landscape, both corporate and natural. Like many of CLUI’s projects, “Suggested Photo Spot” transcends the limits of representational art to bring viewers to the actual site of confrontation, where myths of business and government neutrality, even beneficence, toward the environment are readily exposed.

Most recently, CLUI contributed to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles’ Flight Patterns show, taking museum visitors on a bus two hours inland to their Desert Research Station. The Flight Patterns tours involved an official guide (although visitors could drive to the staffed station on their own), who pointed out land uses of the region, from the freeway to Fontana’s steel industry. “We’re talking about erosion, flood control, industrial development,” says Coolidge. “Heading out into the desert, we try to read the physical vestiges of contemporary history on the landscape.” CLUI’s bus ride was more didactic than Dencity’s, but, says Coolidge, they didn’t “spoon feed” people. “It’s important to initiate an interpretative process,” he says. Additional CLUI tours have been “taken to ridiculous extremes,” says Coolidge. “We’ve taken tours that cover over 500 miles in a day and kind of wear people out. It’s kind of an adventure, an odyssey.”

The voyeurism of the tourist on these buses, traveling past unglamorous, often desolate areas, can turn self-reflective. As the Dencity bus passes through neighborhoods where nearly as many people live as tons of waste are transferred on a daily basis, “you feel suddenly uninvited,” says Erin McGonigle, the sound artist who recorded most of the samples for the electronic mix. “We were cautious about fetishizing the spaces,” says Gabri. “There’s a lot of power being able to be in this bus. Mobility is a privilege, people pay for it.”

Of course, the inverse of the empowered, self-propelled tourist is the refugee, the person involuntarily displaced. Gabri himself is originally from Iran; his family fled the country during the 1979 revolution.

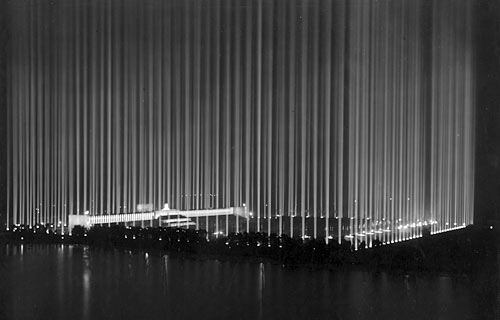

A bus project directly addressing the difference between choosing to move and having to move was proposed by artists Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock in 1995 for Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial Competition. Bus Stop: The Non-Monument engendered controversy even though it was never produced. In the proposal, buses would pull up to the vast, empty space under the Brandenburg Gate in the center of Berlin. There, a waiting hall would offer digitally displayed histories of the destinations, the names of which would also flicker across the buses: Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, the death camps of Nazi Germany. A requirement for the competition was the inclusion of the official project name, which was “The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” As Schnock has pointed out, placing this phrase on the buses would make it a memorial in perpetual motion. In effect, tourists would replicate the constant state of transit that the Jews endured during the Holocaust, as they either fled the Nazis or were shipped to camps. Although their proposal placed 11th out of 528 in the memorial competition (with Peter Eisenman’s “real” monument chosen for construction), it was a public favorite. In 1996, the artists published a 128-page bus timetable that listed the sites that could be reached on current public transportation.

Stih and Schnock are known for antimemorials, or nonmonuments, an idea which latches on to the inevitable change of time and context as our most fundamental reality. Many have argued these structures don’t remember events but bury them in myth. Writers and artists in Germany, still sensitive to the memory of Albert Speer and the Nazi fixation with grand gestures, are particularly aware of the loaded meaning colossal monuments can contain. The traditional concept of a monument only encourages people to contemplate a hulking stone building and an abstracted past; nonmonuments instead create the memorial as process. Rather than distance the viewer, Bus Stop invites participation in that process which, like the Dencity bus tour or CLUI’s ride to the desert, makes travel and the passage of time essential to the art. Tracking the hours, minutes, and seconds in a world where the pace of change seems to compress time itself is the theme of Darren Almond’s Mean Time (2000), a shipping container with a digital display continually ticking off Greenwich Mean Time. The artist rode with the container, linked to a Global Tracking Satellite, from London to New York for his show at Matthew Marks Gallery last fall, documenting the journey with photographs, as well as drawings of the night sky. Almond’s drawings allude to an older tradition of triangulating distance at sea by observing the sun and stars; after the 18th century, longitude was determined by calculating the time difference relative to Greenwich. Only in the past few years have mariners been able to rely on GPS. While Almond’s outsized clock mechanically ticked off the time in England, he was honoring an ancient system of navigation, by taking notations on the sky.

Also journeying to New York City in a freight container was the art collective etoy, best known for the “Toy War” waged when an American online toy store tried to take the European art group’s domain name. The etoy.TANK, one of four bright orange containers sent for a spring show at Postmasters Gallery, is “the office, studio, hotel, storage, and webserver at the same time,” according to the group’s Agent Zai. Members of the group, spread across Switzerland, Germany, and California, reside in these “walk-in webservers” when participating in exhibitions. While the tank provides a physical manifestation of the group’s nomadic nature, the website hosts etoy. TIMEZONE, an online Twilight Zone where minutes count 100 UNIX seconds and a midday time embargo halts the clock for an etoy hour. “TIMEZONE,” writes the group, “is the solution to the insanity of the continuous physical travelling through international time zones, for time shifts in international markets and to the problem of getting older.” Through the eyes of artists like etoy, Dencity, CLUI, and Almond, nomadism today is as much about keeping up with a vision of ourselves and the time we’re constantly losing as it once was about tracking basic things‹food, weather, water‹across the land.

One need not be a member of etoy, however, to travel with attention to one’s creature comforts. With the global traveler in mind, New York’s OPENOFFICE and Denmark’s cOPENhagenOFFICE / Tanja Jordan created the NorthousEastWest (NhEW). The NhEW is a portable dwelling unit, custom-designed for around $7,000, that makes almost as much sense in crowded Manhattan as on the cold expanses of Greenland, where it got its inspiration from Inuit dwellings. Made of an aluminum frame, wood base, aluminum and plastic paneling, with a sealskin rug optional, the entire house can be packed up quickly into a crate. Inside her NhEW, the mobile citizen is at home in the world, no longer a tourist moving through someone else’s garbage-strewn, contaminated community.