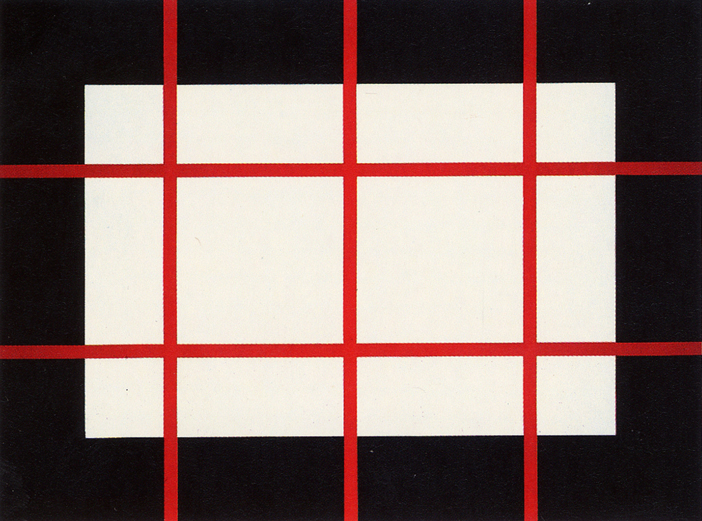

This Donald Judd woodcut caught my eye at Sotheby’s print sale this month, as much for its title as its contrast and complexity: Artists Against Torture, which, well.

It turns out Judd was one of 19 Artists Against Torture who were invited to make a fundraising print portfolio for the Association for the Prevention of Torture. I’m sure there are many more artists against torture, including, no doubt, many women, but for whatever reason, in 1992-3, the Geneva-based NGO commissioned these 19 men to make some art against torture.

So this Judd was a loosie from the portfolio. Which was published in an edition of 150, plus 40 APs, including one for each of the artists, not AP, ed. 40, as Sotheby’s sold it. Anyway it only sold for $3,750, a bargain for a Judd woodcut, so whoever bought it must have known something of the work. [The Judd Foundation sold their copy of the portfolio in that 2006 sale at Christie’s.]

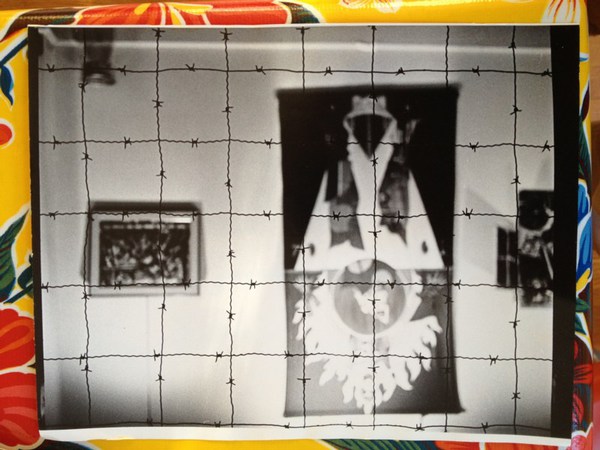

The print reminds me a bit of Barnett Newman’s 1968 sculpture, Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley [above], in which a grid of barbed wire across a window frame protests Chicago’s police brutality against war protestors at the Democratic Convention. But for the similarity to be anything other than a coincidence, Judd would have to introduce representational content and metaphor into his work, which seems impossible. And yet that does look like bars on a cage, doesn’t it? If you let it?

Also I’m kind of interested by Judd’s political involvement. I wouldn’t have expected that, even though I know he was directly involved in mobilizing to protect SoHo. Turns out the Judd Foundation had a show in Marfa in 2011, “The Public Life,” about the artist’s political, social, and environmental activities.

1 May 2014 | Lot 225, Donald Judd, Artists Against Torture (sic), sold for $3,750 [sotheby’s]

APT’s Artists Against Torture portfolio was exhibited at the Ritter Museum in 2012. [museum-ritter.de]

Tag: donald judd

On Metal And The Passage Of Time

Is it just me who can’t stop thinking about that oxidized brass kitchen in Dimore Studio designers Britt Moran and Emiliano Salci’s Milan apartment? The one in T Magazine this weekend, even though it seems like the Women’s Fashion issue, not Design?

BECAUSE HOLY SMOKES.

A couple of things: they also do have that brass slab cabinet/headboard, which kind of dilutes it a bit, or maybe not. It makes me think they ended up with half a truckload of brass from a client project, and were like, well, we could just make everything out of brass?

Also, I guess two years is the appropriate time to wait to shoot an apartment that has already been featured in other magazines and blogs and debuted at international design fairs? Because these pictures by Emanuele Zamponi are all for Yatzer from 2011. Though they do look pretty much exactly like the Times’s photos.

This embedded light strip seems extraneous and unfortunate, though. It will have no place in my oxidized brass kitchen. It looks like a remnant of a planterbox from a corporate lobby, which is always a risk one faces when working with lavishly thick brass, I suppose.

It’s also a fairly stiff repudiation of the elite brass ideology, which, when it is seen on the doors, awnings, siamese firehose connectors, and other brass elements on New York’s finer co-ops, shine brightly as proof of extraordinary, hand-labor-intensive, maintenance. For Dimore, thought, the patina is the point. Splash marks, drag marks buff marks, heat marks, air, it is a new kind of extravagance-through-negligence.

Which, of course, immediately calls to mind the copper pieces of Walead Beshty, both the tabletop-shaped Copper Surrogate wall pieces which appeared at his 2011 Regen Projects show and in last year’s Art Unlimited at Basel [above], which accrete a fine patina through handling and installation; and the smaller, more interesting FEDEX pieces, which really earn their knocks on the street, the handtruck, and the plane. [Now I wonder what the insurance is on shipping these things?]

image via phillips

I remember a discussion I once had with someone from Donald Judd’s operation. They told me how Judd was outraged to find out collectors, and even some museums, would put a clearcoat on their copper or brass stacks in order to preserve the pristine look. But Judd’s preference, I was told, was that you damn well better leave his unfinished finish alone. And if you want it to shine, you polish it. And if you don’t polish it, you let it oxidize.

I actually think of this conversation often, because of the shiny brass Judd floor sculpture at MoMA, a 1968 work given to the museum in 1980 by Philip Johnson. It’s probably the single Judd work I’ve seen the most over my adult life. And I’ll be damned if I’ve ever seen it without some visitor’s grubby handprint on it. Conservation does not remove them immediately, though; it’d just be too much. So when I’ve visited the galleries several times in a week, I’ve noticed the same handprint still there. A calculated balance, I’m sure the museum is aware of how many microns of material they lose with each buffing, and plan accordingly.

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1968, image:moma.org

Anyway, even after all these years, I’ve never been able to look at that Judd and not think of a coffee table. Not once.

On The Restoration Of 101 Spring Street

I don’t know how they knew, but I was asked to write about ARO’s restoration of 101 Spring Street for Architect Magazine. I’ve been a huge fan of Donald Judd’s architecture since I first visited his spaces almost 20 years ago, so I was somewhere between concerned, wary, and freaking out over what was going to happen to the artist’s works.

So I attended the Judd Foundation‘s preview last week [EXCLUSIVE GREG.ORG IMAGES ABOVE, BELOW]. Basically what happened was, after 19 years of life-consuming effort and stress, a shit-ton of money, and a near-fanatical approach to conservation, 101 Spring Street is done and saved. [Well, technically, it’s almost done. Like 99% done.]

The second biggest surprise was ARO’s absolutely amazing transformation of the subterranean levels at 101 Spring into the beautiful, light-filled offices of the Judd Foundation. I’d been in the basement once before, way back when, and it was a dingy, dark, leaky mess. Now the original 19th century sidewalk vaults and floorlights [below] work and look fantastic. Even as they go to extraordinary lengths to preserve their dad’s spaces, Judd’s kids also managed to create something for themselves as well.

Meanwhile, I tried to write about Judd in the empiricist style of Judd. It turned out to be very difficult. And if no one noticed or said anything about it, Ima guess that I was only partly successful at it. Still, a very nice thing to write about.

101 Spring Street by Donald Judd (and ARO) [architectmagazine]

The Judd Foundation will start guided visits of 101 Spring Street in June 2013. [juddfoundation.org]

A de C

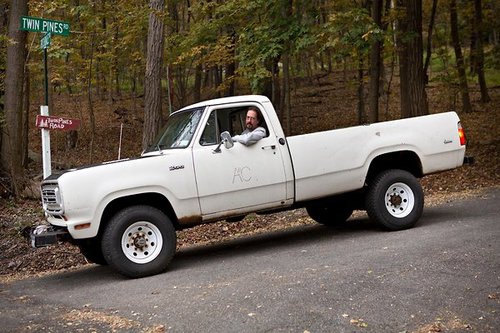

The first and last time I saw this truck, Donald Judd’s ranch truck, was in the early 1990s, in Marfa. I swear this logo for the ranch, Ayala de Chinati–or am I hallucinating?–used to be painted on the door of 101 Spring St.

Anyway, I’ve been looking for it again all these years because I’ve wanted to knock it off for myself, for my letterhead, if not for the door of my truck, and I couldn’t remember exactly how the letters-in-letters thing went. So I’ll get right on it.

An Artist’s Truck That’s No More Than It Needs To Be [nytimes]

The Denver Art Museum In The News

I really shouldn’t do this, but there are just too many for me to hoover up by myself.

eBay seller Lexibell currently has a big stash of vintage press photos from the Denver Post that includes hundreds of pictures from and about the Denver Art Museum.

Among the highlights, this March 1970 shot of the Museum’s highly anticipated, Gio Ponti–designed art fortress. Post staff photographer Duane Howell’s photo ran with a story that in fact, the museum folks were so excited they couldn’t wait until the building’s scheduled completion in 1971, so they were holding their gala there in April.

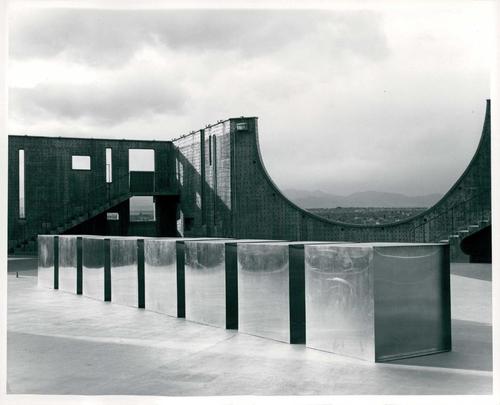

Stunning Judd aluminum boxes on the roof of Ponti’s completed building in 1971. You’re only seeing this now because I bought it, obviously.

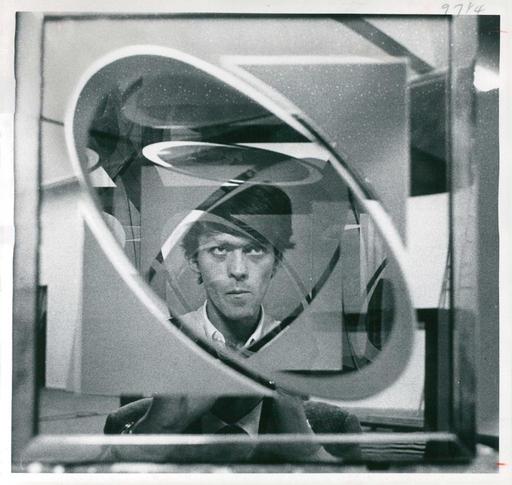

Here’s Ed Sielsky’s 1969 photo of Don Bell looking through a chromium & glass “cube” by “designer” Larry Bell:

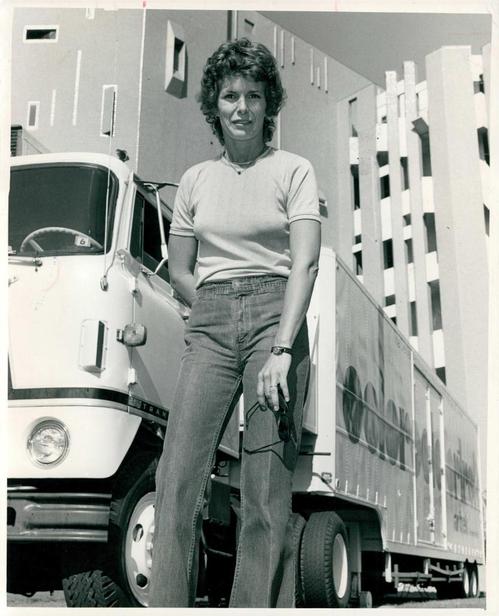

Several shots of Carol Walmsley [“Carol Walmsley likes her job.”]

and her Colorado Artrek big rig, a museum-in-a-semi that she drove around the state, bringing exhibitions and educational programs to citizens beyond Denver.

Which is perhaps inspired by the NEA’s 1971 project, Art Fleet, which was supposed to take masterpieces around to the people in trucks and inflatable dome pavilions. But which never happened.

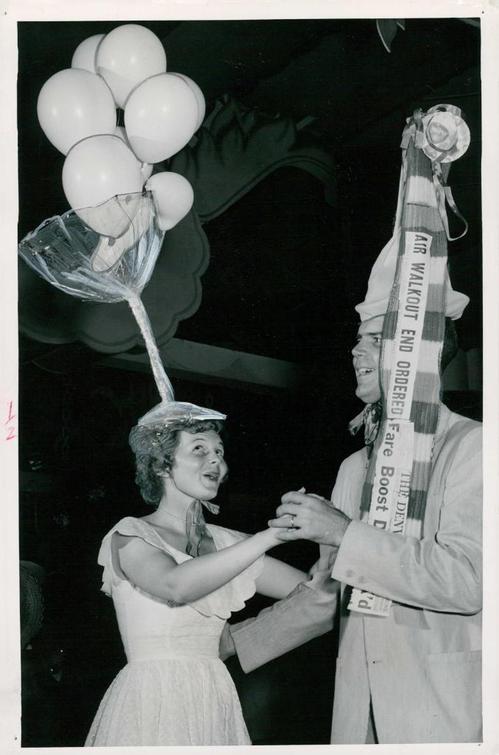

Meanwhile, back in Denver, there are other party pics, including lots of shots of festive hats from the 1951 Mad Hatters Ball. This one looks postively Calder tin can Christmas Tree-esque:

And to close it out, here’s a Jan. 1987 shot by Brian Brainerd captioned, “Celebrities ponder art at the Denver Art Museum.” And yes, that is then-museum director Richard Teitz with/near Ted McGinley with Shawn Weatherly, at a pivotal moment in their careers between Revenge of the Nerds and Married With Children and Police Academy 3 and Baywatch, respectively:

And there are currently 700 more like this.

The Judd Conference

I cannot go to Oregon for the weekend, but I would pay cash money right here and now to watch a livestream of the Judd Conference, the Univerity of Oregon’s day-long exploration of Donald Judd’s fabrication methods. The official title is, “Donald Judd Delegated Fabrication: History, Practice, Issues and Implications “:

From the outside a Donald Judd piece is seamless, hiding all traces of its construction. But behind the final piece is a rich history of the artist’s intent and his method for fabrication. Join us for a groundbreaking discussion of Judd’s art, lead by contemporary art scholars and Judd’s longtime fabricator, Peter Ballantine. The day-long conference in Portland, Ore., will look at Judd as an icon of the American minimalist movement, as well as issues of authenticity and fabrication that continue to have lasting implications for artists today. In addition, the conference will explore the artist’s connection to the Pacific Northwest, where he created a site-specific piece in 1974 for the Portland Center for Visual Arts (PCVA).

Arcy Douglass is running a Judd Conference blog, and of course there’s a Judd Conference Twitter [@juddcon].

Douglass also wrote an article a little while ago about Judd’s large-scale plywood work executed at the Portland Center for Visual Art in 1974. Like the incredible Plywood Slant Judd installed at Castelli in 1976 [which was re-created at Paula Cooper in 2001], it was a site-specific, architectural construction determined in part by the dimensions of the plywood itself.

On second thought, maybe it is best to be there in person. Not just so you follow Peter Ballantine around as he visits his secret local sources for vintage plywood and Oregon Pine. But to get some straight answers about what the hell was going on with this corner of the PCVA installation. Great Caesar’s ghost! [via artnet]

Tim Burton X Donald Judd

Tim Burton was at MoMA yesterday, talking to media folk about a film dept. retrospective of his work, which includes an exhibition this fall of sketches, storyboards, props, puppets, etc. from his wacked out output.

I wasn’t in town for the q&a [here’s a movieline writeup via MoMA’s Twitter] , but the confluence of Burton and MoMA reminded me of one of my favorite art geek moments: spotting Donald Judd chairs in the background of a 2-second shot in the director’s 1993 stop action animated film, Nightmare Before Christmas.

That’s them in the corner there, in a montage where Jack ruins Christmas all over town. Here’s a close-up. They’re pink!

I had really just begun getting interested in Judd’s furniture a year or so before this, so I was pretty attuned. In fact, several months after seeing the movie, I met Rainer Judd to talk about buying some pieces, about differences or changes with the handling of furniture that might follow her father’s untimely death.

As we chatted, I mentioned the chairs Tim Burton had put in the movie, and she was pretty surprised. She knew Burton, it turned out, and knew he was a fan of the work. And yet, she’d never heard about the chairs–or chairs inspired by the chairs–making a cameo.

Never did hear anything else about it. Hope I didn’t get him into trouble.

NY, NY, A Minimal Town

It’s a fine hook to hang a puff piece for the Guggenheim’s minimalism exhibit on: Tour the city with the curators and uncover the minimalism all around us. Should be ideal; so why would I rather take my chances on the Baghdad-Najaf local?

Is it the idea of riding around in a van all day? The constant competition for most nerve-fraying whine between Nancy Spector’s 3-month-old baby and chief curator/clotheshorse Lisa Dennison? (“There is a very real danger that I will start to shop, so we’d better be brief.”)

No, it’s the depressing realization that these supposedly high-octane New York artminds, augmented by artist and prolific writer Liam Gillick, couldn’t have come up with a more unimaginative, uninformative itinerary. With the exception of Donald Judd’s own studio/house in SoHo, their minimalist sites barely warrant looking up as your cab goes by.

Jil Sander (by Spector’s husband) instead of Calvin Klein (by maxi-minimalist and Judd cut-and-paster John Pawson)? The window at the Time Warner Mall instead of the Rose Center Planetarium (which did clear-glass curtainwall first, infinitely better, and happens to be by an actual architect)? Richard Meier’s silly Asia de Cuba or whatever the hell it’s called? (My guess: Lisa’s idea.)

And the piece de resistance: the Seagram building instead of something actually minimalist, like _____(I’m thinking.) This minimalist braintrust actually drinks the Miesian Koolaid, that it’s all about “structure as the expression of the buildng.” Mies was as much about decoration as the next classicist, it turns out, as the renovation of his IIT in Chicago proved. His structure was a veneer on top of the actual structure: aestheticized, artificial, techno-classicist.

[Update: I am not all right on this Mies nonsense, but it turns out I’m even lazier than a vanful of curators. And I’m too bored with their conceit to care. If you’re really interested in minimalism and the grid and its influence on the city, go read the chapter on how laying out the grid led to the development of the skyscraper in Koolhaas’s Delirious New York.