On the bright side, Joshua Caleb Weibley has some pro-tips on stealing a Jenny Holzer. The only catch: you’d have to visit what sounds like a pretty disappointing show at the Guggenheim to get it. Maybe just leave it there.

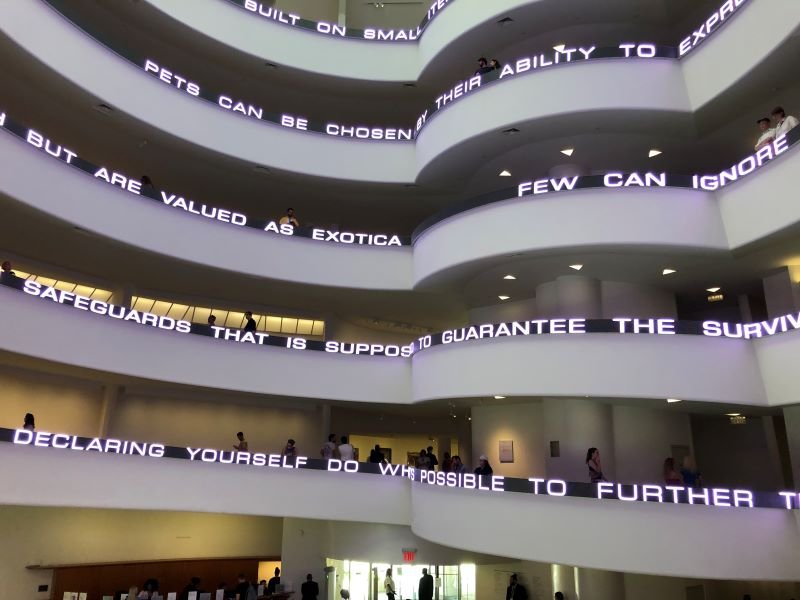

His perceptive and disheartening takedown takes it all down, but it definitely feels like nothing loses more of the plot than the giant LED scroll of Holzer’s Truisms that wraps around the rotunda:

It’s hard to tell—both from focusing on the sentence fragments that have been swirling past you, and from the ambiguously worded description of its materials—just how much of “Untitled” is generated thoughtlessly by Artificial Intelligence. Some phrases are non sequiturs, but others sound plausibly Holzerian. What would the difference be one way or the other? If it is only the seizure-inducing strobe effects that are somehow the product of an AI, how would that differ from other programmable randomized effects? Whatever form of embellishment the technology is adding to her 1989 formula, it somehow lands as much like an afterthought as a desperate grasp for relevance.

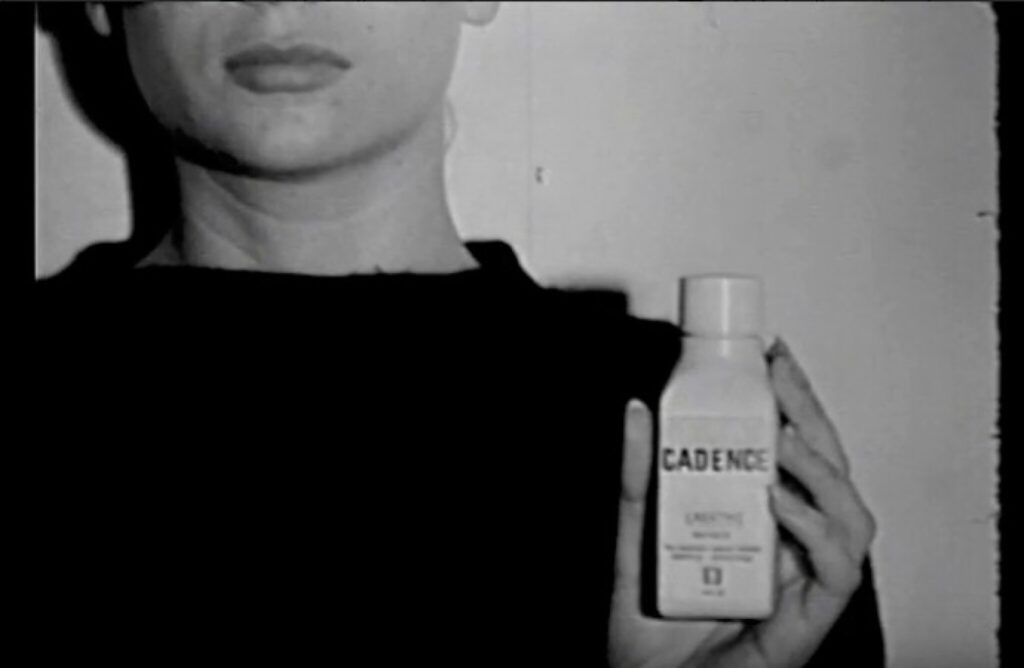

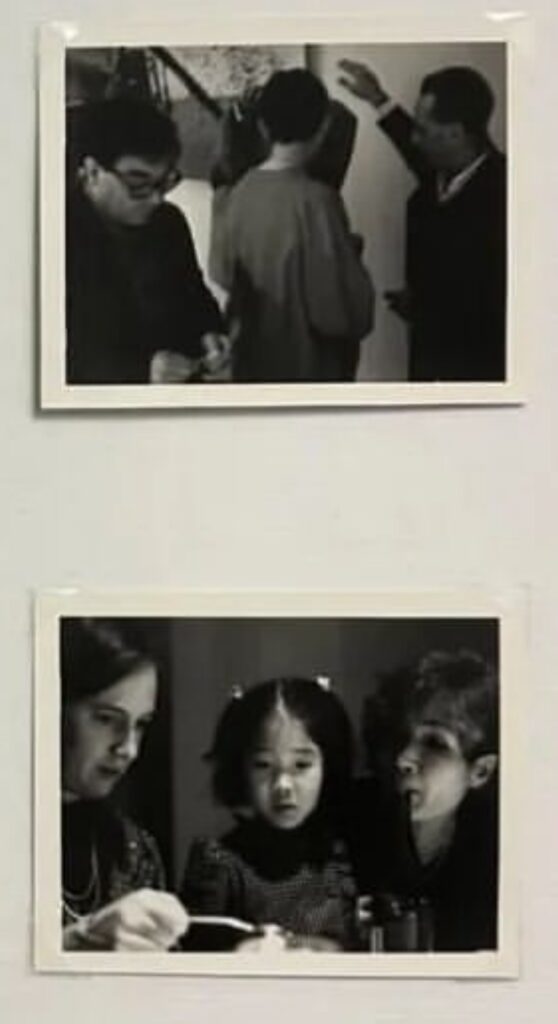

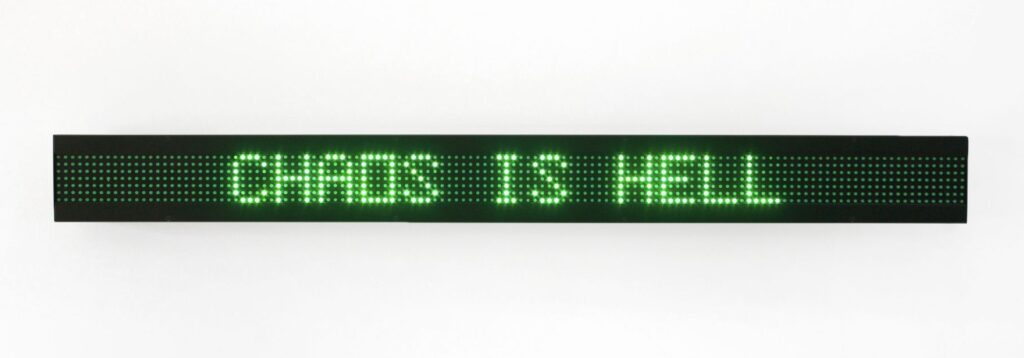

Which, I looked up video of the installation on Instagram and refuse to link to it, what a mess. But that was only after noticing the difference in Weibley’s own photos of the work [above]; Holzer’s signature work is looking its best here, and that is problematic enough. Up top the work shows a high-res white font, while above it switches to a throwback font, in lower-resolution and two colors, which approximates the older diode technology Holzer’s scrolling text pieces originated on, but on an obviously high-res screen.

As a project Holzer’s Truisms have succeeded precisely because they exist in near-infinite formats, from wheatpaste posters to bookmarks to sushi platters to onesies to condoms. As art objects, though, the Truisms are locked aesthetically and collectibly, into a highly specific medium, which is now obsolete: the single-color, seven-diode scrolling ticker signs of the 80s and 90s.

Though it wasn’t clear in 2009 when she did a Q&A with the NY Times, pegged to her retrospective at the Whitney and the launch of limited edition Truisms floor lamps and table lamps in collaboration with Flos, Baccarat Crystal, and Philippe Starck, Holzer was about to become another casualty of the pivot to video: “In For Chicago I have first-time access to a video-compatible L.E.D. array, and I’m in the process of learning how best to program this system. The presentation possibilities, including speed, motion, orientation, brightness, background, and complex double speak are novel and considerably greater than those for older strip signs.”

The process does not seem to have gone well. Jenny Holzer LEDs should be, like Dan Flavin flourescents and Agnes Martin & Ellsworth Kelly paintings, on our culture’s bucket list of things to fill the rotunda of the Guggenheim with at least once. It’s too bad that it didn’t happen sooner.

[no sooner do I post this UPDATE: I check my email and find an invitation to a 2-day Guggenheim Symposium, “Compositions in Light & Language: Conservation of Jenny Holzer’s LED Artworks” at the end of the month. So at least they know.]

Steal This Holzer: Jenny Holzer Light Line Review [interlocutorinterviews]

Previously, related: Jenny Holzer Sushi Platter

Better Read 027: Jenny Holzer’s Arno, as ‘grammed by Helmut Lang