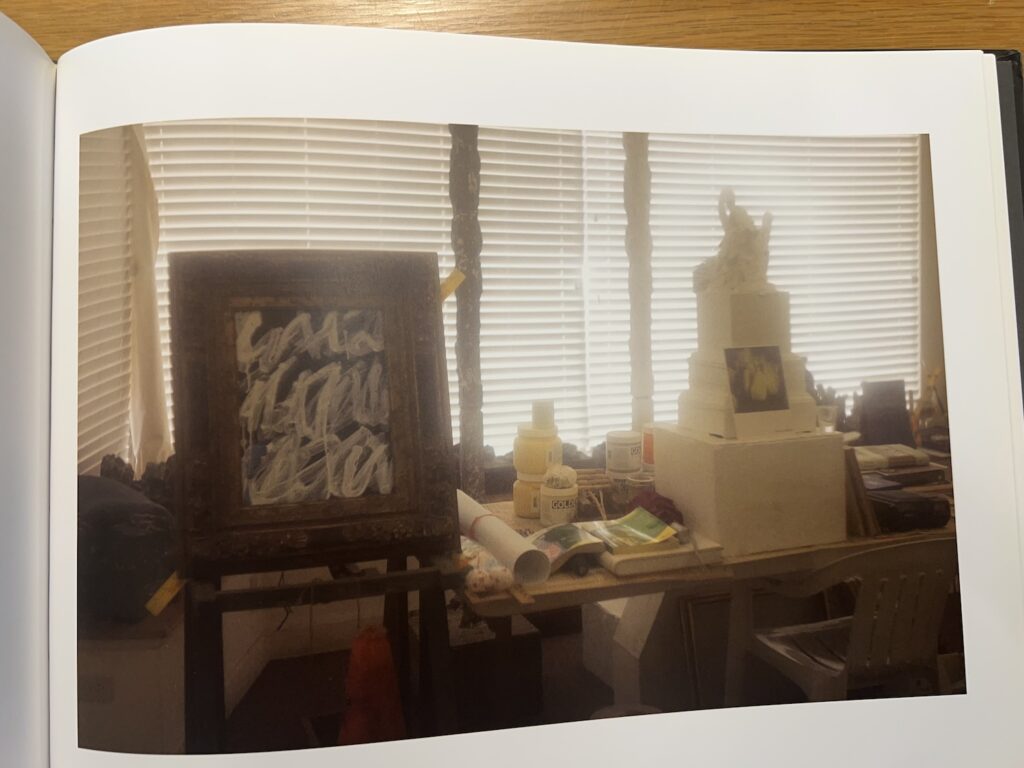

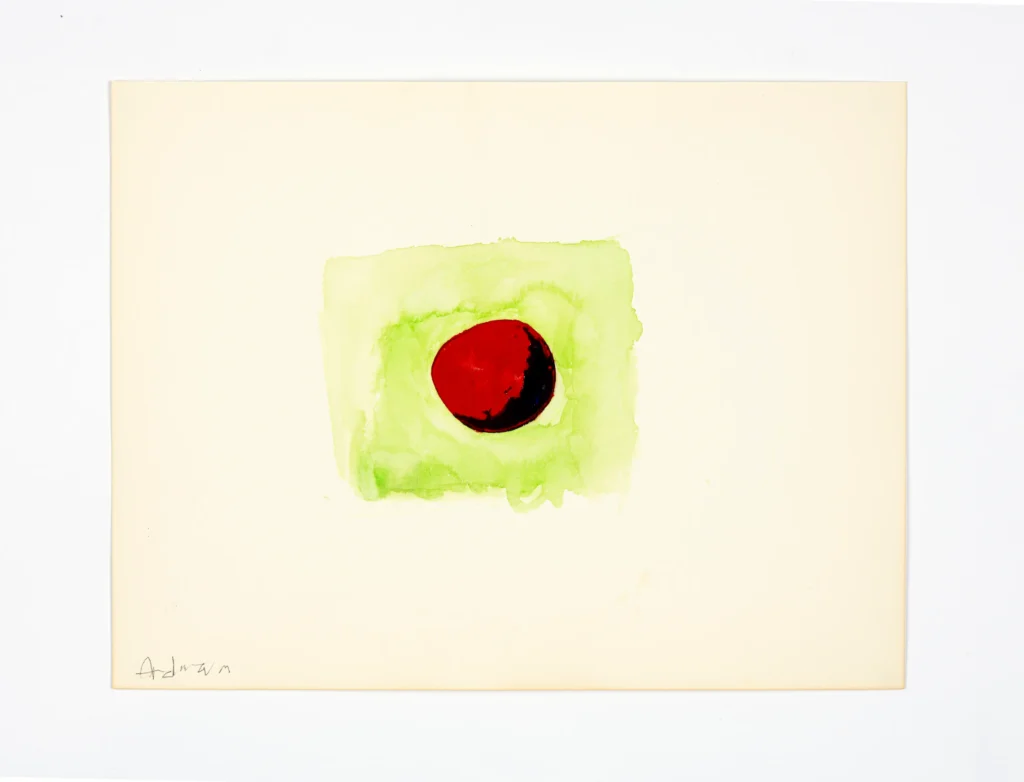

Looked through Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington, Sally Mann’s 2016 book of photos of Twombly’s places, for the first time the other day, and saw this. A perfect little painting in a fat, baroque giltwood frame in his cluttered storefront studio.

But this is not just any perfect painting. [I don’t actually know what painting it is, tbh.] I just know it was a major plot [sic] in Tacita Dean’s 2011 film, Edwin Parker.

Maybe plot is a little strong. In her quiet, attentive film Dean doesn’t follow Twombly around so much as just be where he is, and observe. And for most of the film, he’s in this little studio. The first action or narrative drama, such as it is, involves a painting that has fallen out of this picture frame, and Twombly tries to fix it. The two men with him—first, Butch, his local assistant, and then Nicola Del Roscio—alternately hover and jump in to help with tape and a tape measure.

When I had a review copy of Edwin Parker like ten years ago, I got kind of fixated on this painting, wondering what it was, where it was, and taking grainy screencaps so that I could track it down.

When the Hirshhorn was wrapped in his giant curtained scrim, the swag and slightly lurid colors made me worry Twombly’s painting was by Nicholas Party. When I was making Facsimile Objects about inaccessible Dürers in German museums, I wondered if it was the freely painted verso of something more mundane.

![a google streetview screenshot of the back of a durer painting in the state museum in karlsruhe, germany, which is mounted on a white pedestal in a black and gold edged frame. the back of the painted panel is swirling red green pink blue, pale yellow, interpreted as a slice of agate, and I forget what's on the front. some devotional image of jesus [love him, don't get me wrong, but not the point rn] the gallery floor dominates the image; it is strip wood. the walls are pale grey with a dark grey stone baseboard. google streetview cruft and ui elements abound obv](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/durer-ecce-homo-verso-google-streetview-1024x717.jpg)

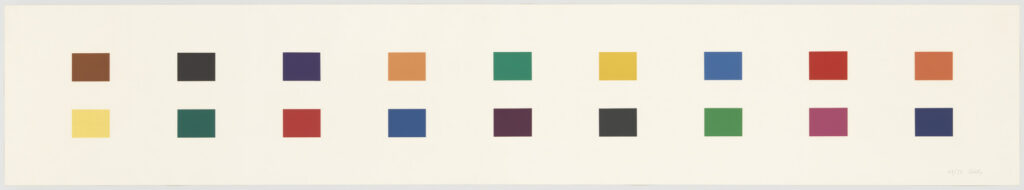

Later in the film, Del Roscio is holding the blue & white painting up top, flipping it around, as Twombly says it’ll fit in the frame. It looks like it’s related to the series of paintings Twombly made for the Louvre in 2008, as part of his ceiling deal.

So the plot, such as it is, involves the swapping out of one painting for another. Technically, this climax does not happen in Edwin Parker; Del Roscio is only shown setting the little painting carefully against the wall.

Whether that makes Mann’s photo a spoiler, a sequel, or just a post-credits teaser, I cannot say. All I know is now I have two little paintings to track down.

![a robert rauschenberg screenprint of a collage made of clippings from newspapers in 1969, includes [clockwise from top left] a photo of cars stranded in the snow; a white woman in a miniskirt with a longer skirt drawn over her; a comet; ted kennedy, some racist judge nixon tried to put on the supreme court who eventually got voted down because twelve republicans still had enough conscience left to be shamed over unalloyed white supremacy, can you even imagine? anyway, several articles and photos of gm assembly lines and the threat of robots and depleted pensions; a chevron tanker truck overturned on a freeway; a hand holding a case of birth control pills; a sideshow entrance with the world's largest rats; a coal mining ship and a truck being craned onto a ship; more assembly line; and a ship docking on the hudson pier. from the 26-print portfolio known as Features from Currents, being sold at Wright 20 in apr 2025](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rauschenberg_currents_portfolio-wright20-202504-283-1001x1024.jpg)