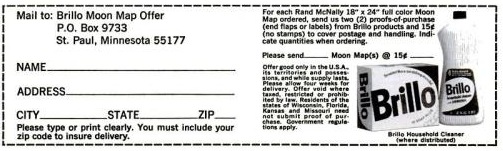

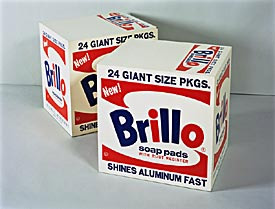

The Moment has a Q&A with Mike Bidlo, whose work, Not Warhol (Brillo Boxes, 1964), 2005 is currently on view in the Lever House lobby:

Did you ever meet him [Warhol] more formally?

Yes, at a party at Jean-Michel Basquiat's loft. There was a big group of people there, but I knew he knew who I was. It was a little awkward.

What about Gerard Malanga?

I was with him on a Brillo Box symposium in Nuremberg, Germany [in 1999] with Arthur Danto and others. He might come to the opening. To me he's the expert.

Malanga is the expert because he, along with Billy Name, did much of the fabrication of those first Stable Gallery Brillo Boxes in 1964. But everyone knows that story. What I want to know about is this "Brillo Box Symposium."

According to a footnote at warholstars.org, The International Symposium for Andy Warhol's Brillo Boxes was held "under the auspices of the Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Nuernberg, Friday, 19 November 1999." Danto presumably discussed his 1998 paper, "The End of Art," which took Brillo Boxes as the inflection point of a 3,000-year art historical cycle or something.

Malanga's paper titled, "How we made the Brillo Boxes," was reprinted in his 2002 book, Archiving Warhol. It provides the most familiar accounts of Malanga, Billy Name, and Warhol painting, turning, screening, and turning all seven varieties of the box sculptures in the first couple of months of 1964. [Four Stable Gallery boxes sold at Christie's in 2006 for $973,000.]

But the 1964 Brillo Boxes aren't the only ones Warhol made. Or Bidlo. Or--well, hold on. Back to The Moment:

If your Brillo Boxes shouldn't be considered a simple substitute for the originals, what should New Yorkers be looking for?

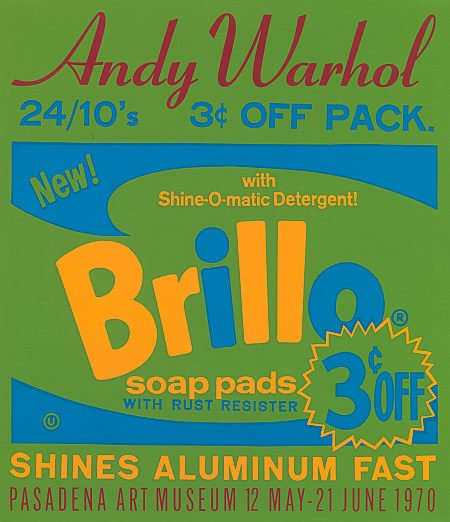

There are so many more layers. When you start peeling back the layers you see that Warhol did all these different versions himself. There's the Stockholm version, there's the Pasadena, the original Stable gallery version. So really it's about learning about the different providences [provenances? -ed.] of the piece, the situations that they were made for.

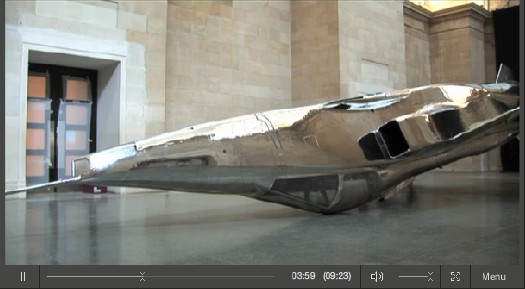

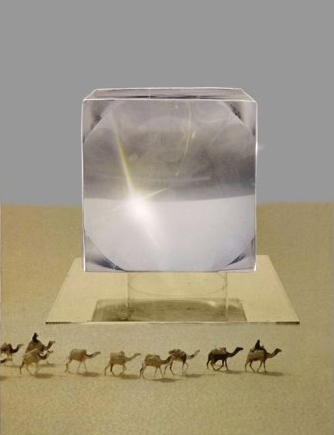

The image above is from the Tate Magazine, of

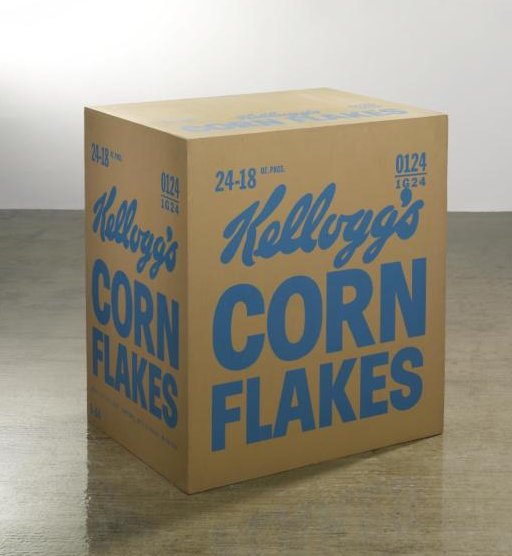

Not Warhol (Brillo Boxes, 1969), 1991, and is Bidlo's replica of the 100 boxes Warhol authorized the Pasadena Museum to fabricate in 1969-70 [LACMA was allowed to refabricate 100 Kellogg's boxes. Warhol donated both sets of boxes to the respective museums.]

And before that, there were the 100 boxes Warhol authorized Pontus Hulten and the Moderna Museet to make in Sweden for the 1968 show organized by Kasper Koenig. Or was it 500? Or was that 500 actual cardboard Brillo Boxes bought from the company and 100 wooden ones to fill in? Or 10?

Until 2007, everyone thought they kind of knew. Or they didn't think much about it. Then some Swedish investigative journalists from Expressen reported that no wooden boxes were ever exhibited in 1968, only cardboard.

And the 94 1968 "Stockholm Type" Brillo Boxes which passed the Warhol Authentication Board's test, and were accepted into the 2004 catalogue raisonne, were actually part of a batch of 105 boxes Hulten fabricated in 1990, three years after the artist's death, in Malmo, Sweden. And that Hulten represented them as 1968 works in shows in St Petersburg and Copenhagen that year. And that he sold at least 40 of them in 1994 as 1968 works. [Does that include this group of 10?] And that he gave six of them to the Moderna Museet in 1995 as 1968 works.

Yow. "Provenance: Acquired directly from the artist by Pontus Hulten, Stockholm" - Christie's, 1998.

The Authentication Board hastily examined the Stockholm Type boxes and issued a letter to owners, saying there were two types of Stockholm Box, one of which might actually have been made in 1968 or so. Maybe there are 10 of those. But there are no documents so far authorizing either those 10, or the 105 Hulten made, only the Stable Gallery and the Pasadena boxes, that's it. So far. And yet they fully accepted the Stockholm Boxes, no sweat. At this point, the only thing the Warhol Foundation people are saying is that they had nothing to do with this mess.

But what in the world was Pontus Hulten thinking? I mean, come on, the guy's a modern art museum demigod who founded the Moderna Museet, the Pompidou, and MoCA. It's not like he really could have just thought, "What the hell, I'll order me up 100 Brillo Boxes and start showing, selling, and donating them as if they're from 1968." Could he?

Did Hulten get authorization from Warhol in 1968, then not really use it [all], and just assume it was still valid? ArtNews quotes an unidentified source as saying that Hulten fabricated his 1990 boxes at the Malmo Konsthall with the help of its director [and Hulten's friend] Björn Springfeldt. Surely he could characterize how he and Hulten talked about the motives and assumptions for the production. [Factcheck: ArtNews says Springfeldt was director of Malmo Konsthall in 1990 when these boxes were fabricated. Actually, he had quit in 1989, to become director of Moderna Museet. He succeeded Olle Granath, who had succeeded Hulten, and who had been a co-curator of the Warhol show, and who was directly involved in its installation. He also owns three Stockholm Style Brillo Boxes he says were made in 1968. If there's anyone in the Swedish museum world not directly implicated in this story, would you please raise your hand?]

How different is Hulten's situation from, say, Giuseppe Panza's later controversies over authorization and remote fabrication of work by artists like Judd, Flavin, Andre, and Nauman? Does this Brillo Boxes question dovetail with the emergence of artists' certificates and minimalist-style, no-artist's-touch production? Are there other examples lurking out there where artists phoned a piece in, then didn't actually get involved--or even see--the final product? I'm going to guess yes.

If ever there were a time for another Brillo Box Symposium, it's right now.

"Andy Warhol's famous Brillo Boxes," from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, August 2007 [myandywarhol.eu]

2007 Authentication Board letter explaining the history and production of Warhol's box sculptures [zimblo.com]

Nice hustle, Art News: "The Brillo Box Scandal," Nov. 2009 [artnews.com, link updated to archive.org Sept. 2016]

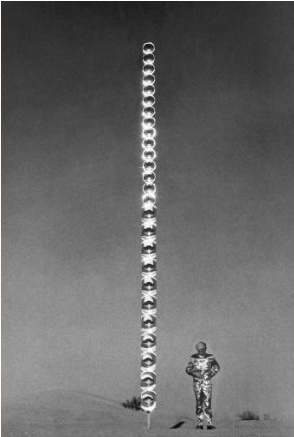

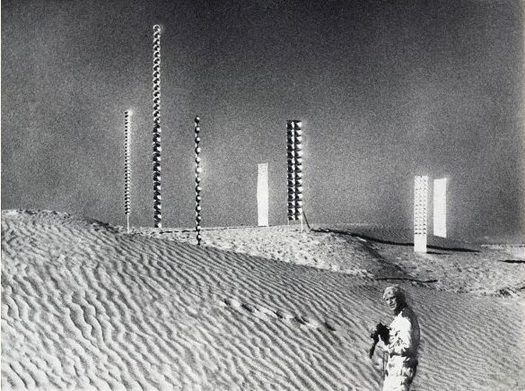

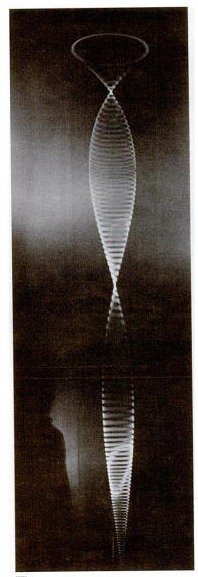

I'd known Laszlo Moholy-Nagy's 1930 kinetic sculpture Light Space Modulator indirectly as a film subject, and then in 2002 through incredible color photographs Oliver Renaud-Clement showed at Andrea Rosen in 2002. [And again, in direct relation to the artist's sculptures in 2007.]

I'd known Laszlo Moholy-Nagy's 1930 kinetic sculpture Light Space Modulator indirectly as a film subject, and then in 2002 through incredible color photographs Oliver Renaud-Clement showed at Andrea Rosen in 2002. [And again, in direct relation to the artist's sculptures in 2007.]

How much of this is really unanticipated, unexpected, unsurprising, and ultimately, unauthorized?

How much of this is really unanticipated, unexpected, unsurprising, and ultimately, unauthorized?

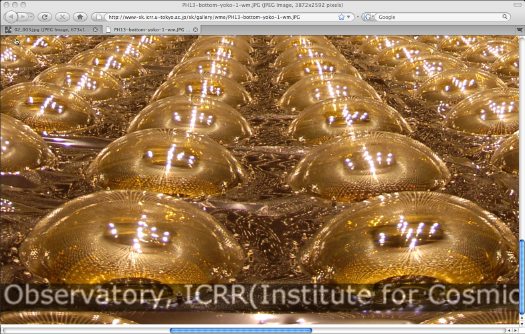

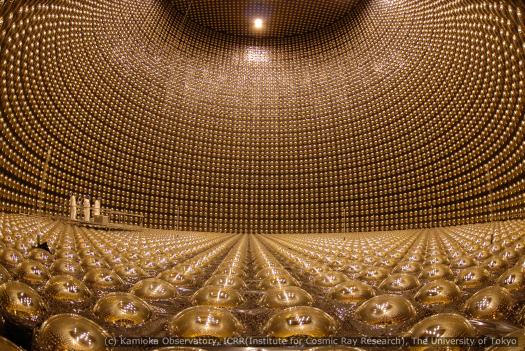

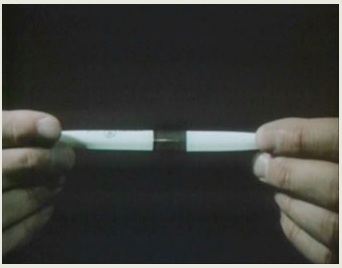

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world's largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the

Photomultiplier Tubes, or PMT, are vacuum tubes used to detect electromagnetic energy. In 1979, Hamamatsu Photonics began development of the world's largest PMT, 25 inches across, which would be used in the