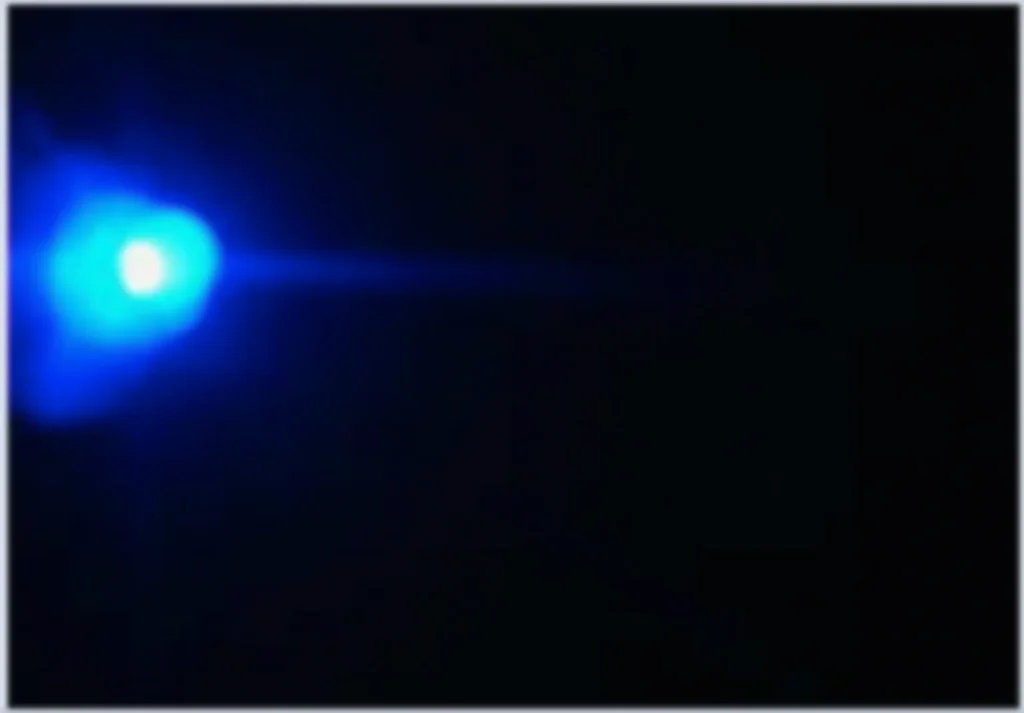

How has there not been more Concerto in Black and Blue content floating around? Do people not go to Hauser & Wirth LA anymore? Is the glow of people recording themselves on their phones ruining it? David Hammons has restaged his epic 2002-3 work in LA. It’s on til June MAY 25. So grab a little flashlight and become the artwork.

Meanwhile, Ursula has a great essay by legendary filmmaker, gallerist and Hammons whisperer Linda Goode Bryant, who filmed the opening night of Concerto in Black and Blue at the vast NYC outpost of Ace Gallery:

He allowed me to be inside for the opening, to make a short film of what happened inside. And what people didn’t know is that David was actually in there himself that night. I only knew where he was because I had a microphone on him. But he was otherwise totally invisible, moving around among everyone else, watching what they did and what they made, present and at the same time absent.

LGB talks incisively about walking and seeing with the artist, and getting hints of how he sees and works. It confirms my theory/suspicion/last-ditch hope that we are in fact living in David Hammons’ world, and often just don’t realize it.

[MAY 2025 UPDATE?? IT REALLY TAKES UNTIL MAY?] Nereya Otieno’s review of Concerto in Black and Blue explains the online silence and invisibility of Hammons’ extraordinary show: You have to bag your phone to enter. She did manage to get installation shots, though. And in some places Hauser still says it runs through June 1, and others say May 25, so don’t get stuck missing it.

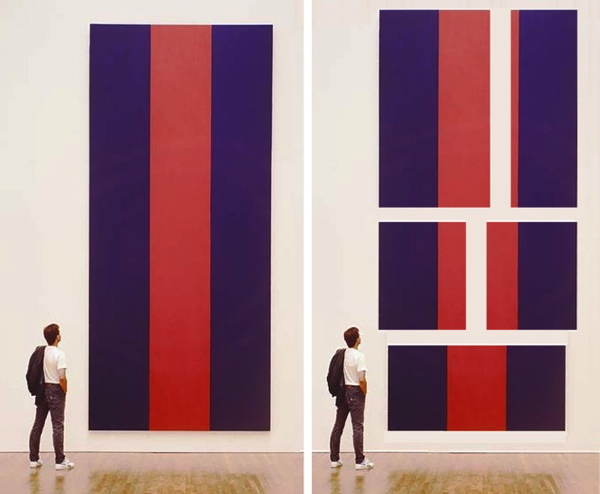

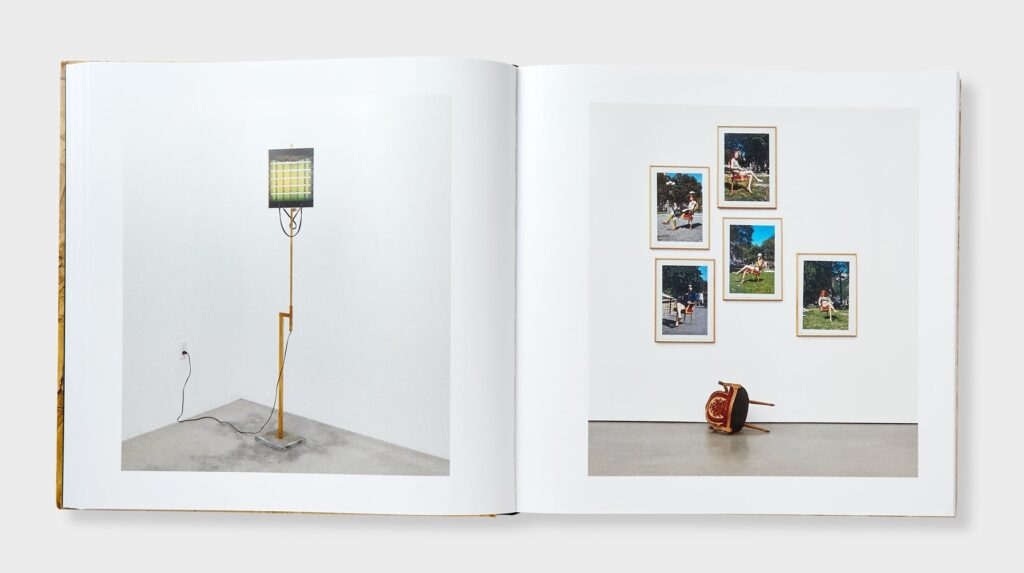

Meanwhile, the book finally documenting Hammons’ sprawling 2019 show at H&W LA is out now, not in May, which means the lamp with the Flavin X Sotheby’s shopping bag lampshade I had to scavenge screenshots in the backgrounds of peoples’ youtube videos like a dog to see is now beautifully photographed on its own.

A Walker in The City | Linda Goode Bryant [hauserwirth/ursula]

David Hammons, Concerto In Black And Blue, 18 Feb – 1 June 25 May 2025 [hauserwirth la]

untitled_picksimg_large-6.jpg, 2025 [greg.org]

Previously, related: Untitled (unnamed.jpg), 2019

Previously, related jpg constraint, alternate naming convention: Untitled (300 x 404); Untitled (290 x 404)

![a robert rauschenberg screenprint of a collage made of clippings from newspapers in 1969, includes [clockwise from top left] a photo of cars stranded in the snow; a white woman in a miniskirt with a longer skirt drawn over her; a comet; ted kennedy, some racist judge nixon tried to put on the supreme court who eventually got voted down because twelve republicans still had enough conscience left to be shamed over unalloyed white supremacy, can you even imagine? anyway, several articles and photos of gm assembly lines and the threat of robots and depleted pensions; a chevron tanker truck overturned on a freeway; a hand holding a case of birth control pills; a sideshow entrance with the world's largest rats; a coal mining ship and a truck being craned onto a ship; more assembly line; and a ship docking on the hudson pier. from the 26-print portfolio known as Features from Currents, being sold at Wright 20 in apr 2025](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rauschenberg_currents_portfolio-wright20-202504-283-1001x1024.jpg)