What’s a bit of art writing that you loved? That stuck with you? That made you think? That made you cringe? That made you want to see something? That made you want to say something? Something in a review? A critique? An essay? A blog post? A social media post? A press release? An auction catalogue? A wall text?

If you read an amazing, short piece of art-related writing recently, why not hold up to the light, so we can all marvel at it together?

Call the greg.org voicemail at 34-SOUVENIR (347-688-3647) and leave a message with:

* your name or handle [optional],

* you reading one brief art-related text [e.g., a sentence or two, 200 hundred or so words, a paragraph max, not the whole thing]

* the writer and source.

You can quote yourself, and if you’re sitting on a gold mine of great texts, you can call more than once, but please keep it to one quote per call. And no slop, bots or twitter.

When I get enough, I’ll edit them together and post a compilation here with links to the sources. Will that be in a day? A week? A month? Never because the idea of making a voice call is ridiculous? I have no idea!

So your recording may be used [unless it’s hateful or absolutely sucks, obv, editor’s call], but any other info goes nowhere and nothing is done with it.

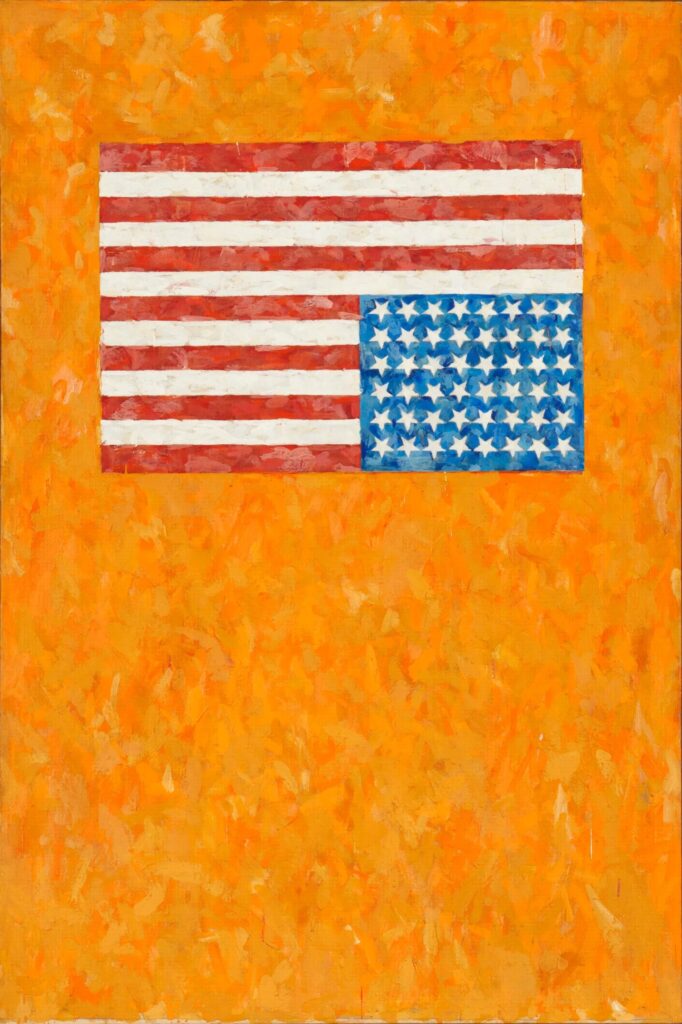

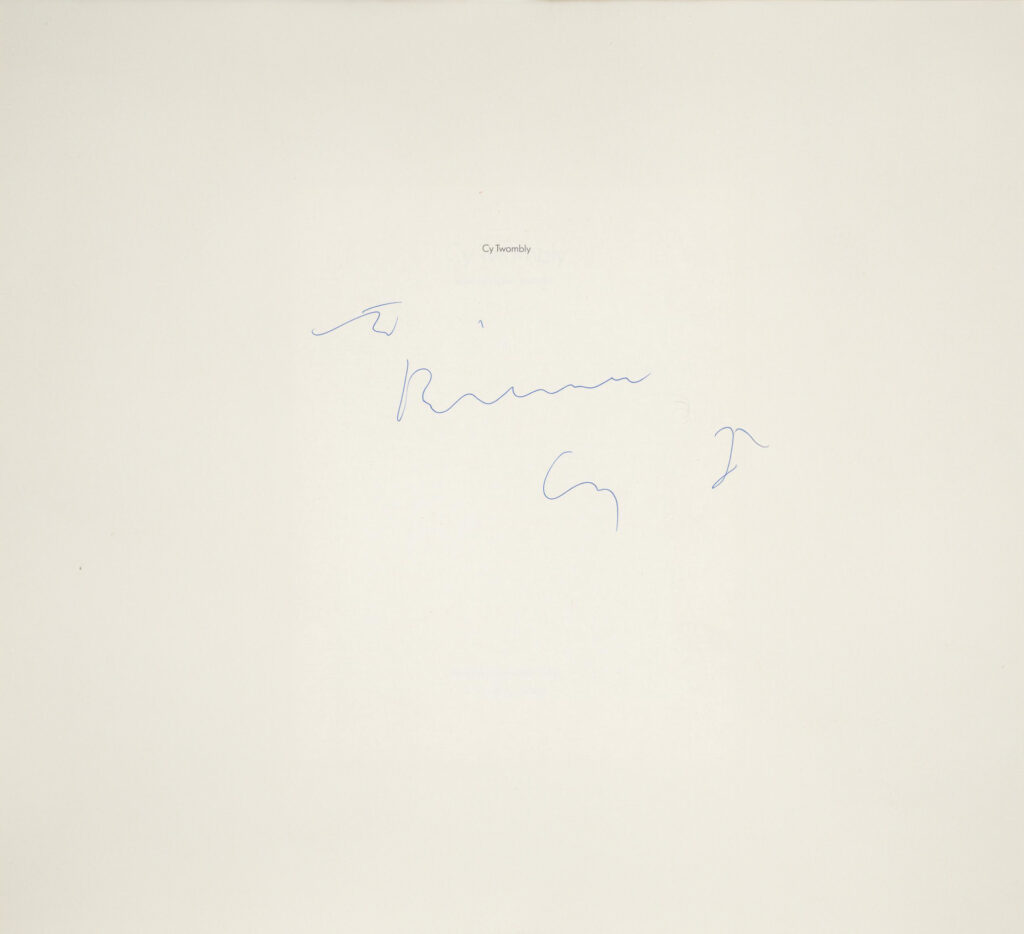

For mine I’m gonna go with either a couple of lines from My night with Cy, the notes Tacita Dean made while spending the night in the Menil’s Twombly galleries, which are inserted in Cy Dear, her new book from the Menil & MACK books, or nine words I could never have imagined before, and which I now can’t imagine being without: “This copy of Ulysses belongs to me, Marsden Hartley.”

[NEXT MORNING UPDATE: After living with this expectation for a few hours, I see that it cannot be a crowdsourced panning for art writing gold, which is anxious and stressful. Instead, I’m treating it as a note to myself, a way to mark, remember, and share a good quote or idea as I find them. So if you read something that makes you think, stop, lol, or smdh, take a second and share it by calling 34-SOUVENIR.]