In June 1997 Tacita Dean was attending the Sundance Institute, and decided to find the Spiral Jetty, which had begun to resurface intermittently starting in 1994.

In 1998 she made an audio work—an installation and an audio cassette edition—titled, Trying to find the Spiral Jetty, and in 1999 she added a slideshow accompaniment, Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah, 1997.

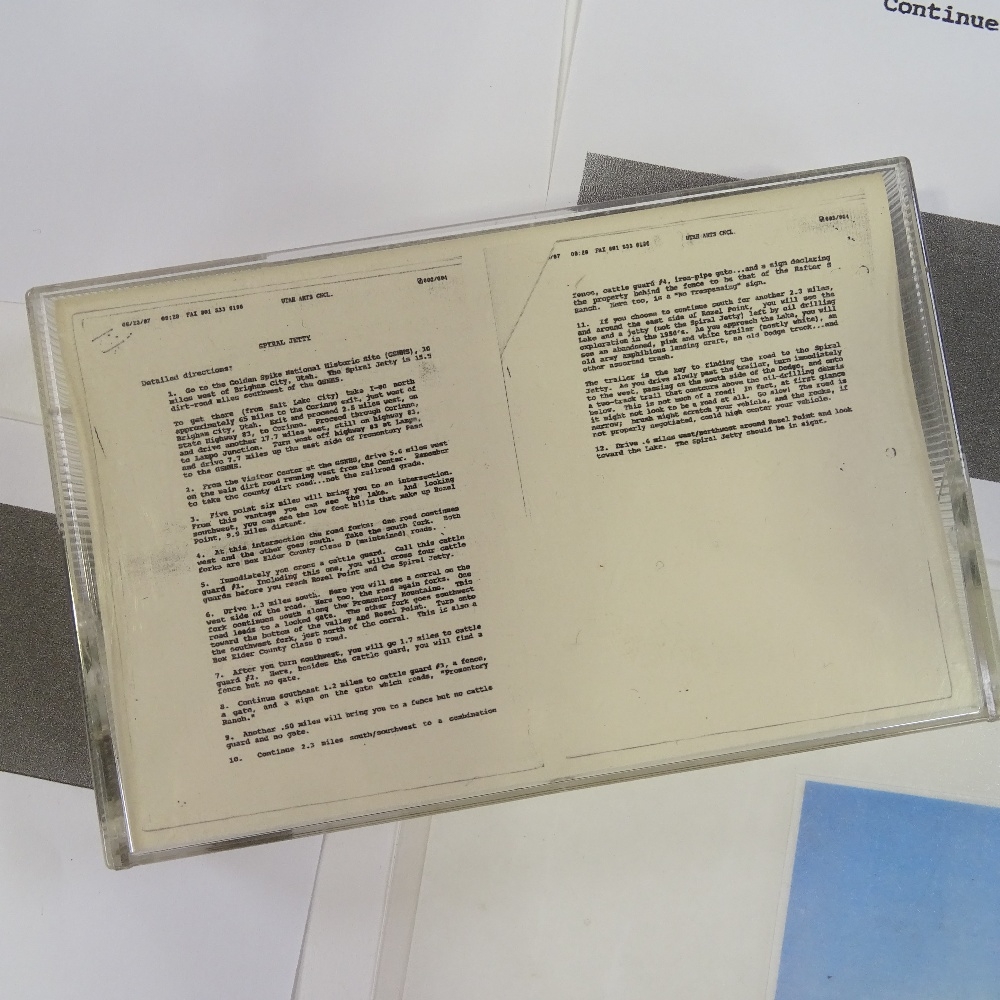

I’ve looked intermittently for years for a cassette edition, and have not heard it, but I do know the cover art: a set of typed directions provided by the Utah Arts Council, which were faxed to Dean at Sundance. [According to Tacita Dean: Selected Writings and Complete Works & Filmography, published by the Royal Academy in 2018, her saved fax is also a work in its own right.]

On a recent search for the cassette, I found a 1999 interview with Dean from Audio Arts, a cassette-based art magazine, which has been preserved by Tate Modern. In it she discusses Disappearance at Sea (1998), a short film for which she was nominated for the Turner Prize, and the Spiral Jetty search and works.

I had always assumed that Trying to find the Spiral Jetty was a field recording, a documentation of the trip made following the directions across increasingly remote and rough dirt roads. But Dean explains the audio is a fabrication, an exercise of memory. She and her companion, an audio engineer named Greg, reconstructed the trip in conversation, and then constructed it anew via Foley sound effects, to augment some ambient recording begun as they approached the lake.

Especially in the earliest, uncertain days of Spiral Jetty‘s re-emergence, and based on her work’s title, it seemed that searching for the Jetty had to be at least as relevant as whether she found it. But I also think that Dean was less concerned with the experienced reality on the ground than the produced reality on the tape. At least that’s how it sounds in her interview.

And of course, the embraced ambiguity worked its way through her practice, and led [as] directly [as possible, via the inspired machinations of Jeremy Millar] to her correspondence with JG Ballard, whose writings inspired Smithson, and to JG, her 2013 anamorphic 35mm film work which circled around Spiral Jetty.