A couple of things that I still wonder about about Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing:

What did de Kooning think? The story of making it is always told by Rauschenberg, or from his side. Did de Kooning ever tell the story? Did he ever see the result? Or talk about it? Did anyone ever ask him about it? I’ve never found any reference at all.

When did Rauschenberg actually make it? The date’s all over the map. SFMOMA currently says it’s 1953. For a long time, it was dated 1953-55. James Meyer had it as 1951-2, but I don’t think I’ve seen anyone else put it that early. Even the extraordinary timeline in John Elderfield’s de Kooning retrospective catalogue has only the basics of Rauschenberg’s travel schedule and his account to go on [“Probably April or After,” it says, since April 1953 was when Rauschenberg returned from his European trip with Twombly.]

[UPDATENever mind. I got the EdKD dating ambiguity mixed up with Johns’ Flag, which has been variously dated between 1954 and ’56, whereas the date for EdKD has consistently been given as 1953 from its very earliest forays into the public view. Thanks to Sarah Roberts, research curator at SFMOMA, who took a moment from her multiyear project documenting Rauschenberg’s work, to point out my error.]

What did people at the time think? Who actually ever saw it? Even someone as early to the work as Leo Steinberg apparently only talked to Bob about it on the phone.

And what about Johns? Who knew about his involvement? What is up with that? For forty-plus years, while Rauschenberg claimed or let others write or publish that he came up with the title, and drew the hand-lettered label, Johns stayed silent about his role in the collaboration. But others surely knew, certainly in the early years when the work was taking shape.

Just before the holidays, I got in touch with Edward Meneeley, and artist and photographer who became friends with many artists and dealers in 1950s and 60s New York because he photographed their artwork. Meneeley created Portable Gallery, a subscription slide service that provided regular installments of art images to libraries, colleges, galleries, and collectors.

I found him because it was his monthly newsletter, Portable Gallery Bulletin, to which Jasper Johns wrote in 1962, explaining that it was artist’s prerogative, plus an agreement between himself and Rauschenberg, not “politics,” behind the refusal to let Portable Gallery publish and distribute slides of Short Circuit.

In a multi-chapter biography published online by Joel Finsel, Meneleey says that he was friends with both Johns and Rauschenberg in the late 1950s, and that he had an affair with the latter behind the former’s back. [He tells Finsel of Johns coming to his loft one morning looking for Rauschenberg, and inviting him in to talk about it, all the while Bob is hiding in Meneeley’s bedroom, eavesdropping on the conversation. Which sounds like a dick move to me, but there you go.]

Anyway, after talking to Meneeley for a while about Short Circuit–which he first saw in 1955, when it was first exhibited at the Stable Gallery–I asked him what people thought or said at the time about Erased de Kooning Drawing.

“Everyone at the Cedar Bar knew,” he told me, but they thought it was just a stunt, a joke. After finishing it, Rauschenberg didn’t do much with it or, as Meneeley put it, “he didn’t know what to do with it.” Until Jasper came along.

[Remember, Bob apparently acquired the original de Kooning sketch of a woman sometime after April 1953. He met and quickly became involved with Johns in the winter of 1954.]

In Meneeley’s recollection of the time, it was Jasper who basically saved Erased de Kooning Drawing from ending up as a barroom one-liner. He mounted it, gave it a title and a label, or really, a drawing of a label. “Bob made it,” Meneeley told me, “But Jasper made it art.”

Which is why I’m interested in hearing what people thought at the time it was made.

Category: johns, rauschenberg, et al

Erased De Kooning Drawing Is Bigger Than It Used To Be

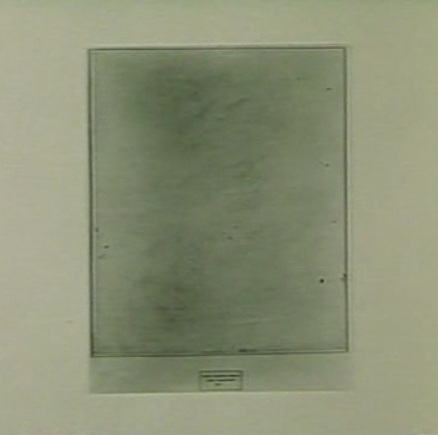

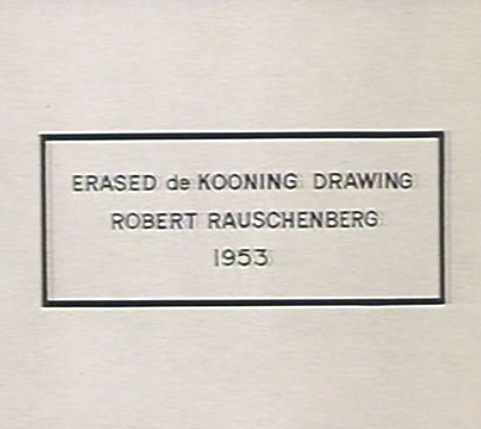

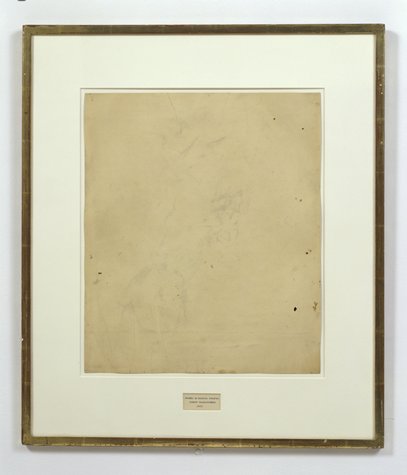

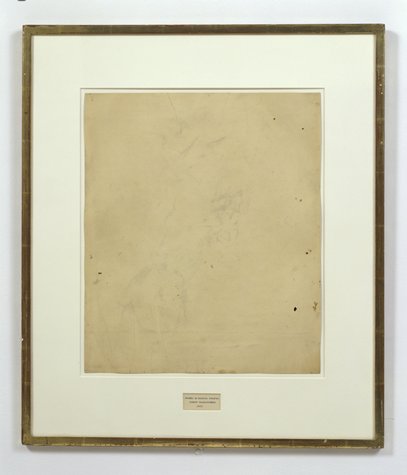

Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, “drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” via SFMOMA

TIMELY BUT UNNECESSARY HOOK: LAST VISIT TO THE DE KOONING RETROSPECTIVE

Part of the reason I hustled back to MoMA Sunday was to look through the de Kooning retrospective from the perspective of his relationship to other artists [or really, vice versa].

Last summer, while mapping out the history of the reception of Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing, I thought Leo Steinberg got it the rightest when he called the work “a sort of collaboration” which treats erasure as generative, not destructive. And sure enough, de Kooning’s drawings and paintings of the 50s are filled with erasures, and smudges, and obliterations; they’re accepted as legitimate markmaking strategies. Which could make Rauschenberg’s project an extension or variation on de Kooning, not a patricidal, rebellious break, as it’s come down to us. There’s a continuity and dialogue right in front of us which we are not-told to ignore.

But while I’m glad to give attention to what I think are Steinberg’s and Tom Hess’s persuasive arguments about the deK/RR affinity, I don’t really have much to add to them.

MUCH OF WHAT WAS KNOWN AND THEN SAID ABOUT ERASED DE KOONING DRAWING TURNS OUT TO BE DIFFERENT OR YES, WRONG

What I’m still trying to pin down are the basics of Erased de Kooning Drawing‘s history. Because it’s become very clear that it has been presented and interpreted differently over time. It was not even exhibited until 10 years after it was made. Many prominent critics, especially those who considered it an ur-Conceptual masterpiece, seemingly wrote about it without seeing it. For decades, Rauschenberg claimed and everyone assumed, that he had created the work alone, but in 1999, when he gave EdeKD to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he revealed that Jasper Johns had given the work its title and had hand-drawn the “label.” And it turns out that Rauschenberg physically altered the work over the years, after exhibiting it at least twice, in ways that have never been addressed.

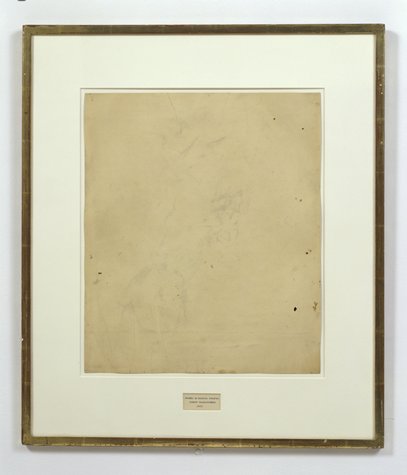

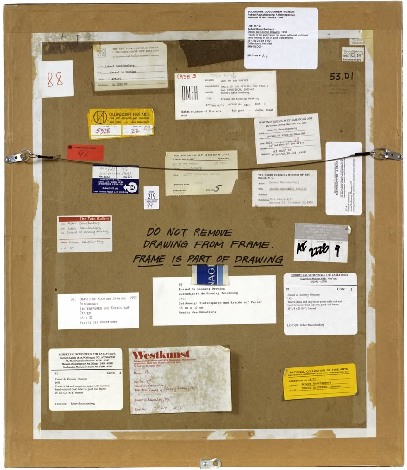

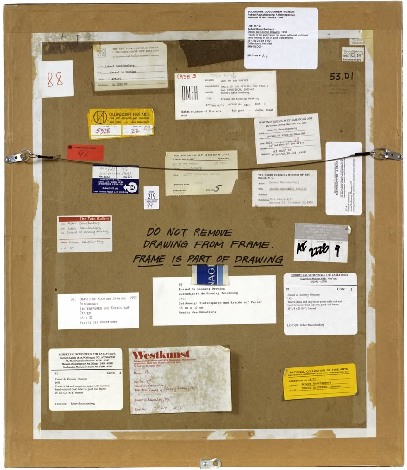

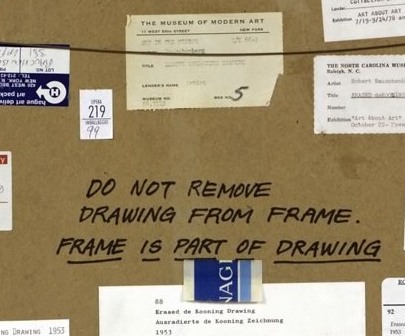

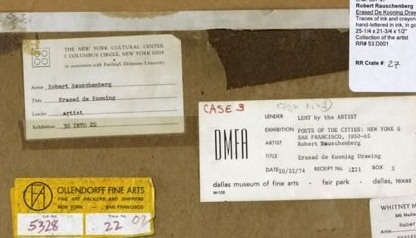

The Erased de Kooning Drawing we know is not just a drawing. According to SFMOMA’s complete description, it is comprised of “traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” To get the point across clearly, Rauschenberg wrote, “FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING“ [all caps and underlining in the original] on the paper backing.

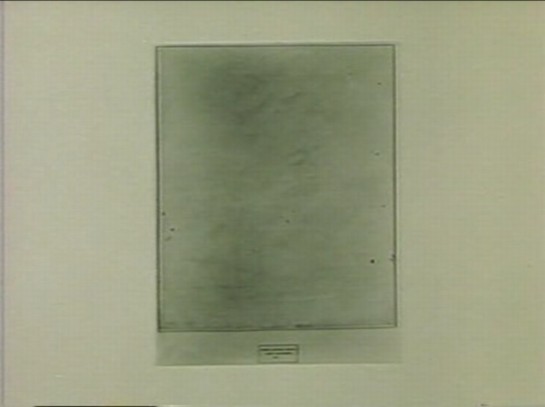

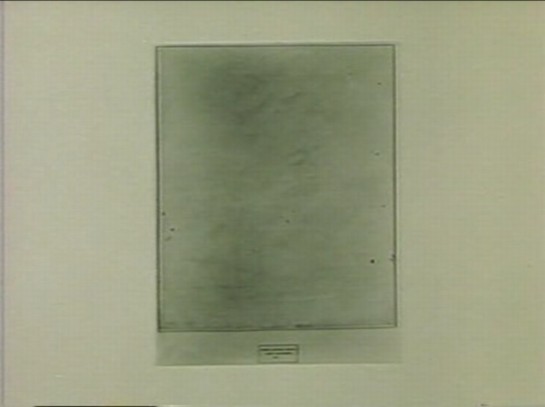

But in Emile de Antonio’s 1970 film, Painters Painting, Erased de Kooning Drawing appears unframed and unmatted. The sheet with de Kooning’s original drawing is mounted on a longer piece of paper on which Johns [it turns out] drew the precise, label-like box of text.

Now I think the way it appeared in Painters Painting is how the artist meant for it to be seen. The earliest exhibition sticker on the back of EdeKD is from 1973. Which made me wonder if the work had even been shown before then. Finally, I found out. Yes. At least twice.

DO WE EVER CALL EDEKD PROTO-MINIMALIST?

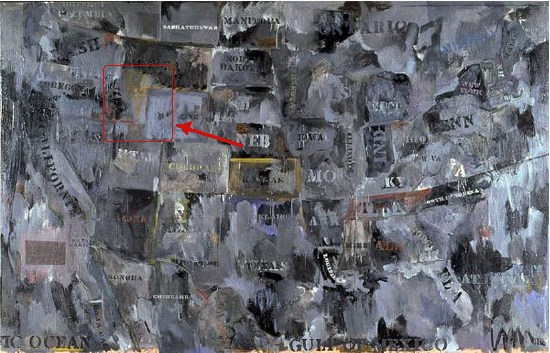

In January 1964, Samuel Wagstaff organized “Black, White + Gray” at the Wadsworth Atheneum. The “Zeitgeist show,” to use James Meyer’s term, came to be considered the first museum exhibition of “minimalism,” and Wagstaff specifically asked Rauschenberg to provide “works that have no color…the sparser the better.”

WERE THERE EVER PHOTOS OR REPRODUCTIONS OF IT BEFORE 1976?

According to the exhibition checklist, Rauschenberg loaned exactly what the title called for: a black painting, a white painting, and a relatively gray work, Erased de Kooning Drawing. The registrar’s record [graciously investigated by Atheneum assistant archivist Ann Brandwein] indicates the work was unframed and unmatted, and that it measured 12×18 inches. [It was also valued at $1,200, but listed as “not for sale.”] There was no catalogue for the 4-week show [Jan 9 – Feb 9], and EdKD doesn’t appear in the few installation photos that survive.

But the piece did get noticed. In her review for The Hartford Times critic Florence Berkman wrote:

Perhaps the most unusual work is one called “Erased Drawing” [hmm] in which two leading artists, Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg are involved.” Mr. Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning drawing, leaving enough of the design so that it can be seen in a strong light.

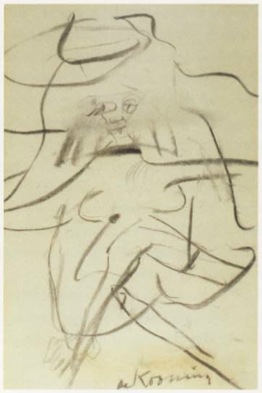

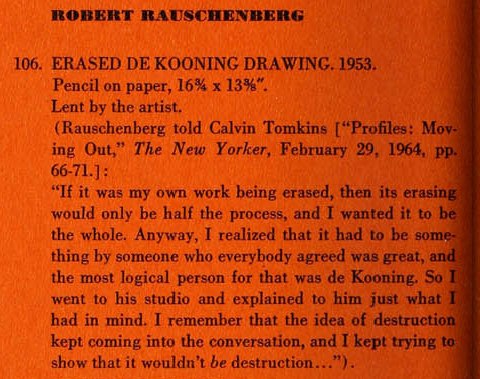

And soon after the Wadsworth show closed, on Feb. 29, 1964, Calvin Tomkins’ first long profile of Rauschenberg appeared in the New Yorker. It included the artist’s first published discussion of EdeKD. When Lawrence Alloway showed the work in his American Drawings survey at the Guggenheim that fall, he included the paragraph from Tomkins’ article in the catalogue checklist, the only piece to warrant [or maybe to require] an explanation:

American Drawings catalogue, p. 60, Sept 1964, curated by Lawrence Alloway via guggenheim.org

Of course, just a couple of months after I chased down and bought my own copy of the catalogue, the Guggenheim released an electronic version on their website.

The dimensions here are slightly different–16 3/4 x 13 3/8 inches–but the medium is the same: “pencil on paper.” Whatever their internal variations, though, the drawing’s 1965 dimensions differ significantly from its current, frame-like object state, which SFMOMA lists as 25.25 x 21.75 x 0.5 inches. Here’s a handy, pixels-per-inch graphic to show the relative sizes.

However it was perceived before the early 1970s, whether as patricidal Dadaist prank or Minimalist forebear, Erased de Kooning Drawing came to be seen as an uncannily prescient, process-oriented, Conceptual object. But that’s not just because the art world finally caught up with Rauschenberg, 20 years later. It’s because Rauschenberg himself reconceived and transformed the work in the wake of, or in response to, Conceptual Art.

Previous greg.org posts on Erased de Kooning Drawing

Johns On Rauschenberg: A Show In Tokyo

Fear not, I have not given up the search for the missing Jasper Johns Flag painting. The one which was in Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine, Short Circuit, a combine which was originally shown with the title, Construction with J.J. Flag. The combine which was the subject of an unusual agreement between the two artists after their bitter 1962 breakup, that it would never be exhibited, reproduced or sold. Which technically did not happen, since the flag painting was taken out in 1965, and Rauschenberg put the piece, with the title, Short Circuit, on a national tour in 1967 as part of a collage group show organized by the Finch College Museum.

Which, point is, in looking for the flag, I keep finding more things I had never heard about Rauschenberg’s and Johns’ time together, a point at which they each were making hugely important, innovative work. And frequently, it seems, they were working on it together. His, mine, and ours.

For a few months now, I’ve been thinking about a letter Johns wrote to Leo Castelli, which I’d come across at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. I’ve been kind of slow to mention it, partly because it just feels a little weird, like going through someone else’s mail. Which I guess it exactly what an archive is, but still. Also, I’ve been wary of reading too much into a single letter, or of over-interpreting a single statement.

But then I’m constantly struck by how frequently a particular phrase uttered in a single interview can get echoed across the writing about an artist, as if that one statement from decades earlier is somehow not just a snippet of a conversation, but a key to deep meaning. So this overdetermining tendency is not mine alone, and whatever, take it for what it’s worth.

In the spring and summer of 1964, while Johns traveled to Japan, he scouted out Kusuo Shimizu’s Minami Gallery for a future Rauschenberg exhibition sometime after the fall. Johns had some pretty specific suggestions about what kind of Rauschenbergs would work in the small, tight space:

I should think that smaller works as different as possible from one another would be good. Or if Bob is going to

use repeatedrepeat images in all the paintings, one work the size of a wall + several much smaller things. If Bob were willing, I think a good effect could be made by having one large painting + several smaller ones which used the same silk screen images but reduced in size. That is, two screens should be made of each image – one large + one small. The opposite would also work – a large painting with smaller images + smaller ptgs. with larger images.

It’s not that Johns is prescriptive, designing his ex-partner’s paintings at a distance. His language is very careful to couch the decisions as Rauschenberg’s to make. But Johns also has a marked fluency in Rauschenberg’s composition and process, and he seems comfortable discussing it, at least with their mutual friend and dealer.

Johns could discuss Rauschenberg’s silkscreening techniques in detail in 1964, even though Rauschenberg only began using silkscreens in 1962, the year the two finally broke up. [Crocus, done in the late summer/early fall of ’62, is one of the first/earliest silkscreen paintings.]

In any case, one more datapoint. As it turns out, Rauschenberg’s show at Minami never ended up happening. Fresh off his hyped and controversial grand prize win at the Venice Biennale, but while he was still also working as the stage manager for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s world tour, Rauschenberg visited Minami Gallery in the fall of 1964.

According to Hiroko Ikegami, Rauschenberg walked in, saw an exhibition of Sam Francis, [“who was still respected and popular” in Japan], and walked right out. Shimizu was offended, and canceled Rauschenberg’s show. Maybe before Rauschenberg canceled it himself, who knows? The Merce tour was a personal disaster for Rauschenberg, and a rift developed between him and Cage and Cunningham which took several years to heal.

Once You Start Looking For A Flag

In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, Jasper Johns, 1961

I’m long overdue for updates on the search for the Jasper Johns Flag Painting that went missing from Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine, Short Circuit. I’ll get to them when I get back home to my files.

Meanwhile, one by-product of searching for a flag: I start seeing them everywhere.

This little multiple by Gabriel Orozco is the first part of a series that doubles the number of rectangles on each sheet.

And on C-Monster, Carolina cropped this time-shifted collage she found on Google Maps into a very flaggish shape.

Hey-Ho, The Art Institute Bought Short Circuit

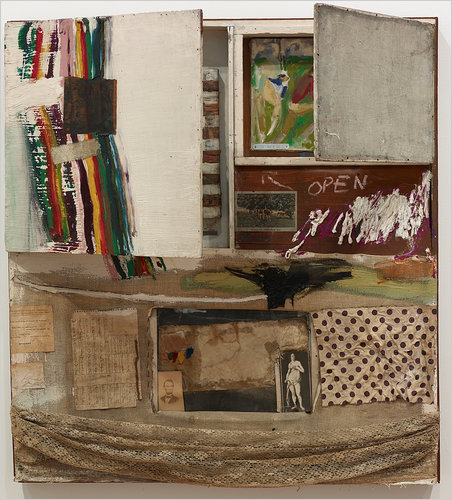

Short Circuit, Robert Rauschenberg, et al, via the estate/VAGA

I always [well, for a weekend or two last December, anyway] figured I’d find the original Jasper Johns flag painting that was inside Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit before the Combine was sold, so that it could be presented to its eventual owner in its original, art history-upending state.

Yeah, well. Turns out the missing flag was not a dealbreaker for the Art Institute of Chicago. Carol Vogel just released the news that James Cuno orchestrated the Museum’s purchase of Short Circuit, Sturtevant flag and all, from the estate, for an anonymously sourced price of $15 to $20 million.

In her piece, Vogel mentions the flag, and the Susan Weil painting, behind the cabinet doors. But then she says something I’ve never heard or seen anywhere: that though both were invited, neither Ray Johnson nor Stan VanDerBeek actually contributed pieces to the Combine VanDerBeek we knew, but Johnson?

I’d always understood that Johnson was in, and I’d assumed that the collage in the center of the lower half, with the Abe Lincoln and Venus postcard, was Johnson’s. If it blended so seamlessly with the rest of the Combine, and with the rest of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre, well, all the better. Johnson was famously sanguine about his collage work, and loved if his artist friends tweaked or reused it. Or so I’m told.

I like this reproduction of the piece, too, with the doors barely ajar. I’ve heard a story from a couple of people now, that when Johns went to Gagosian to see the show, he mentioned that the doors on Short Circuit were supposed to be closed. This image kind of finesses the door, concealing just enough so that the first thing you say when you see the piece is, “Holy smokes, that’s a Jasper Johns flag three years before he showed it anywhere!”

Prime Rauschenberg at Chicago Art Institute [nyt]

Previously: Until I get some tags, this is how you find all the Short Circuit-related posts around here

‘A Sort Of Collaboration’

Erased de Kooning Drawing as of 1999 at SFMOMA

When we last left Erased de Kooning Drawing, the late, great Leo Steinberg had finally told his story about getting Rauschenberg on the phone in 1957 in order to sort the damn thing out. Steinberg’s conclusion was that, far from a “Neo-Dada” prank or Oedipal negation, Rauschenberg had offered de Kooning “a sort of collaboration” of erasure. The plausibility of this interpretation was inspired by the equally collaborative combine painting of the same period, Short Circuit.

Erased de Kooning Drawing, without present matboard, c. 1970, via Emile de Antonio’s Painters Painting

So to recap quickly: EdKD is a collaborative work. In which erasure-as-drawing is the subject, or the strategy. Each artist with his different markmaking method. And it is inscribed, labeled, by hand, with a flatly descriptive title and claim of authorship. And though it had been unmatted at some point [above] rendering the inscription and the drawing as one collaged work, it was matted in a way that obscured this unity, and it was [eventually] presented as a framed, presented object. A conceptual work, realized. A concept of a drawing erased. Hold all that in your head. Am I missing anything?

Erased de Kooning Drawing, detail, c. 1970, via Painters Painting

Anything besides the small detail that the inscription, the text, the third instantiation of the concept, the generative inverse of the erased drawing itself, was made by Jasper Johns?

For the crucial period of EdKD‘s uptake into the art world’s discourse, Rauschenberg had always claimed that he had written the inscription. That he’d “signed” it. That’s what he told Emile de Antonio on top of that ladder. That’s the only way anyone talked about it. But it is not true.

Vincent Katz has made one of the rare references to the importance of the work’s collaborative creation in Tate Magazine in 2006. But others credit Calvin Tomkins with breaking the news of Johns’ involvement in EdKD in his 2005 New Yorker profile of Rauschenberg:

Johns gave Rauschenberg the title for “Erased de Kooning Drawing,” which came into being in 1953, when Rauschenberg persuaded de Kooning to give him a drawing which he would then erase, to see whether a work of art could be created by the technique of erasure; Johns also did the precise lettering for the title, on the framed matte below the very faint, wraithlike ghost of the erased image.

The title, of course, is not on the matte, but under it. It was originally of a piece with the drawing, until the matte separated it, demoted it, even. Which may intensify the implications of difference between pre- and post-matted drawing.

[Tomkins does not identify the source of his revelation about Johns’ involvement, even though he wrote in the same piece that “Johns recently told Joachim Pissarro, a curator at MoMA, that he thought the term ‘combine’ had been his suggestion.” The latter was a memory Rauschenberg apparently did not share.]

Tomkins may have been the first to publish it, but claim of Johns’ collaboration was first made at least six years earlier, by a seemingly unlikely source: Robert Rauschenberg.

In a 1999 video interview about the newly acquired EdKD, Rauschenberg told SFMOMA curators,

So when I titled it, it was very difficult to figure out exactly how to phrase this.

And, uh, Jasper Johns was living upstairs, so I asked him to, to do, the uh, the writing.

And they say you never get to know your neighbors in New York. Sometimes you make historic works of art together with them.

Except that on Pearl Street, as Castelli famously told it, Johns was downstairs. And Rauschenberg was upstairs, in the loft vacated in the summer of 1955 by Rachel Rosenthal, who had found the building in the Spring of 1954. Rauschenberg was certainly around–and living around the corner–before then. They’d met early in the winter of 1954, began and he and Johns had already created and shown Short Circuit by then. So either Rauschenberg was referring to a time before they moved in together, Or Johns didn’t add his pieces to the drawing before mid-1955. Either way, it sounds like the drawing, to use Tomkins’ odd phrasing, actually “came into being” after 1953, the date Johns wrote on it.

Part 1: ‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

Part 2: Erasers Erasing in Painters Painting

Part 3: Norman Mailer on Erased de Kooning and other ‘hopeless’ and ‘diminished’ art

Parts 4&5: Leo Steinberg on EdKD and how it’s a collaboration

Part 6: A 3-Way Collaboration, that is, with Jasper Johns. Oh, that’s this post. Just one more, I think.

Encounters With Erased de Kooning Drawing

You know what, it’s the weekend. We can have two long Leo Steinberg-related posts at once. Read’em on the NetJets to Basel.

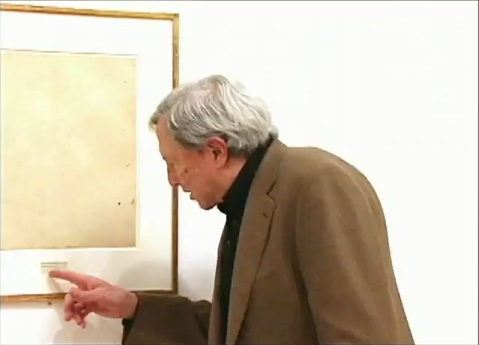

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it’s not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote “Other Criteria.”

Though he mentioned it in his most important piece of writing, which was also the most important piece of writing on Rauschenberg, it’s not entirely clear whether Leo Steinberg had actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing when he wrote “Other Criteria.”

And as he tells the story in his awesome 2000 book, Encounters With Rauschenberg – A Lavishly Illustrated Lecture, Steinberg makes not seeing it the point. I’m really tempted to include all seven pages of EdKD from the 85-page book–the text was published straight from his lectures for the 1997-8 Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim and Menil, and it really sounds just like him. [I met Steinberg in 1991 when the delightfully friendly woman I was sitting next to for his Picasso lecture series at Rice University introduced us; she turned out to be his host, Dominique de Menil. Life-changing, &c, &c. but not right now.]

But I won’t. Even though it’s out of print and expensive. It really should be a PDF now. Anyway.

Steinberg’s take on EdKD is useful here because he was watching Rauschenberg’s career and involved in its critical dialogue almost from the very beginning; he’s about as well-informed or as thoughtful an audience voice as Rauschenberg could find in the 1950s and 60s. And so his reaction seems like a good proxy for the best perspective possible of the time. And it sounds like, though he felt he had to address it, and though he could argue for its critical or conceptual significance, Steinberg didn’t really like Erased de Kooning Drawing very much. It bugged him. He even apologized to his lecture audience for spending “so much time on a negative entity” and a “one-time exploit.” But but!

The lead-in for his story about first encountering EdKD was, interestingly enough, an anecdote from 1961 and Rauschenberg and Johns, about artists putting personal content into their work, and denying it, and then eventually ‘fessing up, and so about not quite trusting what artists themselves said:

That experience confirmed me in a guiding principle of critical conduct: “If you want the truth about a work of art, be sure always to get your data from the horse’s mouth, bearing in mind that the artist is the one selling the horse.”

And did I abide by my principle? I should say not! My longest conversation with Rauschenberg occurred c. 1957, when I first heard about something outrageous he’d done some years before. And rather than going after the outrage–the horse, as it were–I called the trader.

[uh, don’t want to spoil the story arc, but isn’t not ignoring a lesson in 1957 that stems from looking back from the 80s to a 1961 conversation putting the horse before the trader? Just sayin’. -ed.]

The work in question was Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953. The piece had not been exhibited; you heard of it by word of mouth. I did, and it gave me no peace. Because the destruction of works of art terrifies.

See, now this is news right there: not exhibited before, word of mouth, a piece you know and worry about without seeing.

How could Bob have done it; and why? The work is often, and to this day, referred to as “a Neo-Dada gesture,” but that’s just a way of casting it from your thought. Obvious alternatives to Neo-Dada suggested themselves at once. An Oedipal gesture? Young Rauschenberg killing the father figure? Well, maybe.

But wasn’t it also a taunting of the art market?–an artist’s mockery of the values now driving the commerce in modern art?

This would put paid, so to speak, to Norman Mailer’s complaint that Bob was erasing to play the market. Steinberg tells how everyone was very aware/shocked/jealous/disturbed when a de Kooning finally sold for $10,000. And Rauschenberg was the one, don’t forget, who got the angriest at Robert Scull for his market-making auction some years later. But all these seemingly contradictory interpretations, Steinberg pointed out, were just assumptions from afar.

So I picked up the phone and called the horse trader himself. And we talked for well over an hour. Occasionally, thereafter, I considered writing up what I remembered of our talk, but then Calvin Tomkins discussed the Erased de Kooning Drawing in his Rauschenberg profile in The New Yorker, and he did it so well that I thought, “Good, that’s one less thing I have to write.” But I don’t mind talking about it and recalling whatever I can of that phone conversation.

On the first question of why, Rauschenberg gave an explanation similar to the one he’d told Emile de Antonio: he was interested in drawing with an eraser “as a graphic, or anti-graphic element,” and found that erasing his own work was unsatisfying.

As for why de Kooning and not some other pre-existing work of art, Steinberg examines and largely discounts the Oedipal explanation, and instead suggests that Rauschenberg recognized or claimed a kindred spirit, that erasure as a technique was central to de Kooning’s own practice. And yes, this section I’m obviously going to quote at length:

There is another reason, I think, why Bob lit on de Kooning. I live with a de Kooning drawing from the early 1950s–it’s of a seated woman, frontal, legs crossed [below]. The face was drawn, then erased to leave a wide, gray, atmospheric smudge; and then drawn again.

Willem de Kooning, Woman in a Rowboat, 1953

And here is Tom Hess’ account of Bill de Kooning’s working method. I’d like to read you a paragraph from Tom’s book Willem de Kooning Drawings (1972), and I’m encouraged to do this by the example of Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit combine, which, you remember, brought in some of Bob’s friends piggyback. Tom Hess was a friend; hear him describe de Kooning’s habit of draftsmanship.I remember watching de Kooning begin a drawing, in 1951, sitting idly by a window, the pad on his knee.He used an ordinary pencil, the point sharpened with a knife to expose the maximum of lead but still strong enough to withstand pressure. He made a few strokes, then almost instinctively, it seemed to me, turned the pencil around and began to go over the graphite marks with the eraser. Not to rubout the lines, but to move them, push them across the paper, turn them into planes…De Kooning’s line–the essence of drawing–is always under attack. It is smeared across the paper, pushed into widening shapes, kept away from the expression of an edge…the mutually exclusive concepts of line and plane are held in tension. It is the characteristic open de Kooning situation…in which thesis and antithesis are both pushed to their fullest statement, and then allowed to exist together…

This much Tom Hess.

In view of such working procedure, one might toy with this further reason why Rauschenberg’s partner in the affair had to be de Kooning, rather than Rembrandt or Andrew Wyeth. De Kooning was the one who belabored his drawings with an eraser. Bob was proposing a sort of collaboration, offering–without having to draw like the master–to supply the finishing touch (read coup de grace)

I could just go on and on. Steinberg noticed that, despite declaring his early love for drawing, Rauschenberg seems to have pretty much stopped drawing after the early 50s, Erased de Kooning Drawing was really about erasing drawing itself.

And since he brought it up, and in the context of collaboration, too, maybe that makes Short Circuit, which includes two paintings by his partner and ex-wife, a way to wrangle painting into its place, too: subsumed behind closed doors. It’s an admittedly rough analogy, but then, I only just thought of it.

In any case, Steinberg’s collaborative interpretation of Erased de Kooning Drawing is worth holding onto. On with the story:

Meanwhile, Bob and I are still on the phone. And Bob says, “This thing really works on you, doesn’t it?”…Finally, I asked, “Look, we’ve now been talking about this thing for over an hour, and I haven’t even seen it. Would it make any difference if I did?” He said, “Probably not.” And that’s when it dawned on me–it’s easy-come now, but the thought had its freshness once–I suddenly understood that the fruit of an artist’s work need not be an object. It could be an action, something once done, but so unforgettably done, that it’s never done with–a satellite orbiting in your consciousness, like the perfect crime or a beau geste.

Since then, I’ve seen the Erased de Kooning Drawing several times, and find it ever less interesting to look at. But the decision behind it never ceases to fascinate and expand.

It now seems to me that Rauschenberg has repaid de Kooning’s gift to him. For though we all know de Kooning to have been a great draftsman, I can think of no single de Kooning drawing that is famous the way some of his paintings are, except the one Bob erased.

Leo Steinberg On Erased de Kooning Drawing

So ultimately, Norman Mailer’s off the hook. We know that when he wrote about Erased de Kooning Drawing in the 1970s, 1980s, Mailer fragged Rauschenberg for selling it–which he hadn’t–as much as making it. And he got the title wrong: “A drawing from Willem de Kooning erased by Robert Rauschenberg”. Which might mean he never went to see it anywhere it was showing over the years, but it also means he probably felt he got the work, didn’t need to see it. And that he was reading art historian Leo Steinberg’s indispensable 1975 collection of writings, Other Criteria.

That particular wrong version of the inscription on EdKD comes from Steinberg’s title essay, which was first published in Artforum in 1972 as “Reflections on the State of Criticism.” Steinberg originally presented a version of “Reflections” as a lecture at the Museum of Modern Art in March 1968. It was one of a 10-part series of Wednesday night lectures by leading critics and historians [which happens to have been organized by the Modern’s Junior Council then chaired by Barbara Jakobson, which is the predecessor group to the group I chaired for a while, the Junior Associates. Needless to say, I have never felt like a bigger slacker than when I look back at all the stuff the Junior Council did in the 60s. Recordings of the series were restored in 2008, but the Steinberg lecture is not listed among them. I’ll look into that.]

Anyway, Steinberg’s piece is an epic refutation of Greenbergian modernism’s view of both Renaissance and contemporary art. For its compelling critical framework, its defense of content and for identifying what Steinberg called the “flatbed picture plane,” Branden Joseph dubbed “‘Other Criteria’ the single most important article on Rauschenberg’s production.”

Steinberg discussed EdKD along with a 1952 grass painting hung on the wall as an example of Rauschenberg’s early challenges to conventional expectations of orientation:

In retrospect, the most clownish of Rauschenberg’s youthful pranks take on a kind of stylistic consistency…When he erased a de Kooning drawing, exhibiting it as “Drawing by Willem de Kooning erased by Robert Rauschenberg,” he was making more than a multifaceted psychological gesture; he was changing–for the viewer no less than for himself–the angle of imaginative confrontation; tilting de Kooning’s evocation of a worldspace into a thing produced by pressing down on a desk.

Which is interesting, but maybe not quite as interesting as the fact that, as late as 1972 or even 1975, one of Rauschenberg’s greatest critical champions seems not to have noticed that his version of the inscription is actually incorrect. Or that the earliest exhibition date listed on the back of EdKD itself is actually 1973, in a show by an even closer Rauschenberg ally, Susan Ginsburg.

[Interesting sidebar: after posting SFMOMA’s photo of the back of EdKD, a regular greg.org reader told me s/he had seen EdKD getting reframed or rematted “in the late nineties” at Minagawa, and watched as they carefully reattached the archival materials on the back. Maybe Bob was sprucing it up before selling it.]

So anyway, as of the publication of Other Criteria, then, Steinberg considered Erased de Kooning Drawing as a “youthful prank” that was “clownish,” yet prescient. But it’s not clear that the great advocate of close looking had actually seen the work.

Part 1: ‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

Part 2: Erasers Erasing in Painters Painting

Part 3: Norman Mailer on Erased de Kooning and other ‘hopeless’ and ‘diminished’ art

Norman Mailer On Erased de Kooning Drawing, Art

One of the more amusing Erased de Kooning references I’ve come across is from Norman Mailer. It’s reproduced in his 2003 book, The Spooky Art: Thoughts On Writing, but it seems to date from either a 1984 lecture or even a 1974 Esquire Magazine article. Mailer gets things wrong in a helpful way:

The work, when sold, bore the inscription, “A drawing from Willem de Kooning erased by Robert Rauschenberg.” Both artists are not proposing something more than that the artist has the same right as the financier to print money; they may even be saying that the meat and marrow of art, the painterly core, the life of the pigment, and the world of technique with which hands lay on that pigment are convertible to something other. The ambiguity of meaning in the twentieth century, the hollow in the heart of faith, has become such an obsessional hole that art may have to be converted into intellectual transactions. It is as if we are looking for stuff, any stuff with which to stuff the hole, and will convert every value into packing for this purpose. For there is no doubt that in erasing the pastel and selling it, art has been diminished but our knowledge of society is certainly enriched. An aesthetic artifact has been converted into a sociological artifact. It is not the painting that intrigues us now but the lividities of art fashion which made the transaction possible in the first place. Something rabid is loose in the century. Maybe we are not converting art into some comprehension of social process but rather are using art to choke the hole, as if society has become so hopeless, which is to say so twisted in knots of faithless ideological spaghetti, that the glee is in strangling the victims.

Yow, OK. To the extent that Rauschenberg wanted to create an imageless drawing, upon which would be projected the passing shadows of meaning and ideology, I think Mailer has helped him succeed.

Mailer’s focus on the non-existent financial motivations behind Erased de Kooning Drawing seem to show his fight is elsewhere. Not only did Rauschenberg not sell the work for more than 35 years, and only then at a discount to a museum, he actually destroyed a gift, a valuable drawing from one of the highest-paid artists of the time, when he himself was dirt poor and relegated to painting on newsprint.

But combined with his specific error on the inscription, Mailer’s market-centric misreading does help identify the source for his anecdote: it was Leo Steinberg, one of the first and most important critical voices on Rauschenberg’s work. Steinberg, whose major works like Other Criteria, require you to leave the screen and head to the shelf, old-school.

Before Steinberg, though one more from Mailer. He attributes this story [or non-story, as it turns out] to Jon Naar, the photographer who collaborated with Mailer on the epic 1973 book, The Faith Of Graffiti:

Years ago, back in the early Fifties, he conceived of a story he was finally not to write, for he lost his comprehension of it. A rich young artist in New York in the early Fifties, bursting to go beyond Abstract Expressionism, began to rent billboards on which he sketched huge, ill-defined (never say they were sloppy) works in paint chosen to run easily and flake quickly. The rains distorted the lines, made gullies of the forms, automobile exhausts laid down a patina, and comets of flying birds crusted the disappearing surface with their impasto. By the time fifty such billboards had been finished–a prodigious year for the painter–the vogue was on. His show was an event. They transported the billboards by trailer-truck and broke the front wall of the gallery to get the art objects inside. It was the biggest one-man exhibition in New York that year. At its conclusion, two art critics were arguing whether such species of work still belonged to art.

“You’re mad,” cried one. “It is not art, it is never art.”

“No,” said the other. “I think it’s valid.”

So would the story end. Its title, Validity. But before he had written a word he made the mistake of telling it to a young Abstract Expressionist whose work he liked. “Of course it’s valid,” said the painter, eyes shining with the project. “I’d do it myself if I could afford the billboards.”

I was waiting for an infant Dan Colen to crawl into this story, but alas. He must have read it in art school.

On Erased de Kooning Drawing, Cont’d

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, “drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” via SFMOMA

So the basic question, “What do we really know about Erased de Kooning Drawing and how do we know it?” Is really driven by some recent discoveries that my understanding of the work and its story–its history–turns out to be wrong. Incomplete. Based on some assumptions that should, it turns out, be questioned.

For example, Erased de Kooning Drawing is regularly referred to know as one of Rauschenberg’s most important works, which prefigured or influenced entire movements in contemporary art. But so far, I haven’t found actual evidence that the work was even exhibited before 1973. It’s barely even discussed in the 1960s literature on Rauschenberg, never mind the 50s [It supposedly began shocking the art world soon after its creation in 1953.]

I’m always kind of torn between trying to figure this stuff out by piling on the research and citations and sifting through it, and then posting about it, and just documenting my inquiry, incomplete as it may be, as I go along.

I guess the key here may be laying out what freaked me out, and saying that it kind of blows my mind precisely because I’ve been spending so much time looking back at the relationship and collaboration between Rauschenberg and Johns, and at the stigmatized silence that continues to distort our view and our understanding of their crucial, early work.

A week or so ago, I saw a digitally remastered version of Emile de Antonio’s 1972 documentary, Painters Painting [Here’s the vanilla Ubu version.] De Antonio was a longtime friend of both Johns and Rauschenberg; he helped them get their earliest job together as window dressers for Bonwit Teller. I saw a 1976 note in the Smithsonian archives where Walter Hopps says that Bob called de Antonio “a hustler.” He became a complex and controversial filmmaker with a 10,000 page FBI file. For Painters Painting, he conducted extended interviews with both artists and a critically disparate range of others on the scene [the film was mostly shot in 1970]. According to my MFA brother-in-law, the film is a hilarious staple in art schools, which I think I object to; I may take on the film’s content and form head-on at some point, but not now.

Rauschenberg recounted the story of making Erased de Kooning while sitting atop a ladder in front of the church-like windows of his Lafayette St studio. His delivery is deadpan, deliberately ridiculous, and not a little drunk. De Antonio’s editing is kind of disruptive, but the issue isn’t whether erasing the drawing took “nearly three weeks” or a month, or 15 erasers or 40. The issue is Erased de Kooning Drawing itself:

There’s no frame. And no mat. No nothing, just the drawing. Which feels substantively different. De Kooning’s original sheet appears to be mounted onto the piece of paper onto which the label was drawn. Where the mat now seems to separate the label and the drawing, without it, it seems like one thing. A collage, perhaps, but a joined, unified, self-contained whole.

Which makes the label not just a label, but a text, a set of marks, as much a drawing as the erased marks–or the erasure marks. Rauschenberg’s explanation to de Antonio is different from other, later tellings, and from the neo-dada, Freudian interpretations of others. He seems entirely clear about what he wanted to do:

One of the things I wanted to try was an all-eraser drawing. And, uh, I did drawings myself, and erased them. But that seemed like fifty, fifty. And so I knew I need to pull back farther, and like, if it’s gonna be an all-eraser drawing, it had to be art in the beginning.

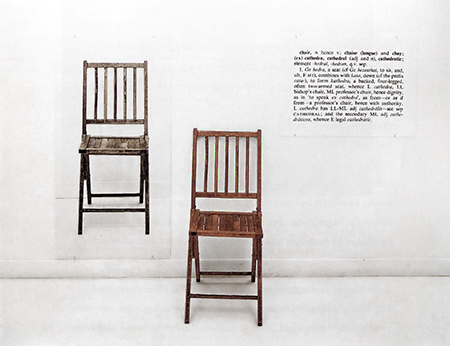

He was trying to make a mark with an eraser. It’s the difference between erasing a drawing, and drawing with an eraser. And when he was done, the result was both an erased de Kooning and a drawing. And the hand-drawn label declared as much. It’s almost a perfectly symmetrical prefiguring of Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, made a dozen years later.

But did Kosuth know and react to Erased de Kooning Drawing in creating his piece? Did de Antonio just happen to shoot the drawing while it was out of its frame, or did it look different–was it constituted differently–in 1970? And before? When did it change to the conceptual object, where the label is demoted, no longer an integral element, diametrically opposite but co-equal with the “drawing,” the concept, but now a separated, ancillary presentation device equivalent to mat and frame? Rauschenberg wrote on the back of the work, “FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING,” but I’m not sure that was always the case.

It seems to me that Erased de Kooning Drawing became one thing in the early 1970s, but before then, it was something else.

Previously: ‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

Next up: looking back at what was said and written and known and shown about Erased de Kooning Drawing before 1973.

‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

How do we know what we know, and when?

For instance, we know that Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is one of Robert Rauschenberg’s most important, influential works. It’s the kind of commonly accepted history that lands a piece in the Final Four of Tyler Green’s Art Madness poll to determine America’s Greatest Post-War Artwork.

And we know the story of it, how Bob took a bottle of liquor with him to Bill’s studio to ask for a drawing to erase. And how Bill, at first reluctant, twice-validated the sacrifice by giving away “a drawing he’d miss” and which would be “hard” for Bob to erase. And then Bob signed it and framed it and sparked an art world scandal with it which hasn’t really abated. We know this because Bob and then his curator and critic advocates repeat the story so frequently. [Vincent Katz has a nice telling of it in Tate Magazine in Autumn 2006.]

But this weekend, I suddenly had cause to wonder just how all this went down, and when, really, did this revolution start? Because it’s not as clear or as obvious as I had always assumed.

That’s Erased de Kooning Drawing up there, precisely matted and framed. That’s how I saw it for the first time in Walter Hopps’ “Rauschenberg In The Early 1950s” show at the Menil 20 years ago, and then again in John Cage’s “Rolywholyover” a couple of years after that. [Or am I conflating the two Guggenheim SoHo versions of those shows?]

At the time, it was still in the artist’s own collection. In 1998, SFMOMA acquired it along with a group of other Rauschenberg works. [Calvin Tomkins wrote in the New Yorker in 2005 that MoMA was offered the works first and turned them down.] Its official description: “drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” It’s not just a drawing, not just an erased drawing, it’s an object assembled.

SFMOMA has a nice little, c.2000 interactive that includes the back of the piece:

“DO NOT REMOVE

DRAWING FROM FRAME

FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING”

LOVE THAT. I could geek out staring at the backs of artworks all day. Did Bob himself write that? It looks like it.

The early line on Erased de Kooning was either “neo-dada,” which was a standard critical reaction to Rauschenberg in the 50s, or AbEx patricide. But it has since evolved far beyond these bad boy, enfant terrible readings, to be considered a precursor of huge swaths of contemporary art.

In his 2009 book, Random Order: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-Garde, Branden Joseph discussed Erased de Kooning Drawing as one of the touchstones of conceptual art and appropriation art, alongside Marcel Duchamp’s mustache-on-the-Mona-Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q:

Whether by defacement or effacement, the two works’ devaluation of the appropriated representation (an essential factor in the process of allegorization) is equally effective. Rauschenberg’s subsequent mounting of the erased sheet of paper within a gold frame, together with the addition of a carefully hand-lettered label with a new authorial attribution, title, and date (“Erased de Kooning drawing / Robert Rauschenberg / 1953”), simultaneously doubles the visual text with a new signification and calls attention away from the (now depleted) visual aspect of the work and toward the conventional and institutional devices of the work’s “framing.”…For Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing essentially reenacted the reception of his White Paintings: the initial evacuation of expressive or representational meaning in favor of transitional, temporal forces subsequently gave way to a process in which meaning was reattributed to the work from the outside.

Indeed it was. As the White Paintings were to the reflections and shadows in the room, so Erased de Kooning Drawing was to passing theories of art.

In 1976 Bernice Rose put “the famous Erased de Kooning drawing” along side Jasper Johns’ Diver at the foundation of The Modern’s major survey, “Drawing Now.” Reviewing the show for the New Yorker, Harold Rosenberg dismissively labeled Pop, Minimalism and Conceptualism, the work that followed Rauschenberg’s and Johns’s “parodies of Action painting,” as the new “Academy of the Erased de Kooning.”

Later that year, the drawing was in Walter Hopps’ Rauschenberg Retrospective at the Smithsonian, which traveled back, in 1977, to MoMA. Where it prompted Grace Glueck to open her NY Times story with a rhetorical question–“Wasn’t it only a couple of years ago that Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning?”

Yes, only a couple, give or take twenty four. Maybe it just took that long to get it. We had to wait for Conceptualism to be invented before anyone could recognize Erased de Kooning was its foundation.

In the September 1982 issue of Artforum, none other than Benjamin Buchloh discussed Erased de Kooning Drawing‘s historical importance in a sprawling 14-page essay titled, “Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary Art”:

At the climax of the Abstract Expressionist idiom and its reign in the art world this may have been perceived as a sublimated patricidal assault by the new generations most advanced artists, but it now appears to have been one of the first examples of allegorization in post-New York School art. It can be recognized as such in its procedures of appropriation, the depletion of the confiscated image, the superimposition or doubling of a visual text by a second text, and the shift of attention and reading to the framing device. Rauschenberg’s appropriation confronts two paradigms of drawing: that of de Kooning’s denotative lines, and that of the indexical functions of the erasure. Production procedures (gesture), expression, and sign (representation) seem to have become materially and semantically congruent. Where perceptual data are withheld or removed from the traditional surface of display, the gesture of erasure shifts the focus of attention to the appropriated historical constrict on the one hand, and to the devices of framing and presentation, on the other.

Whew. But.

Back up. Because here is Buchloh’s account of the gesture, and of the “device of framing and presentation”:

After the careful execution of the erasure, which left vestiges of pencil and the imprint of the drawn lines visible as clues of visual recognizability, the drawing was framed in a gold frame. An engraved metal label attached to the frame identified the drawing as a work by Robert Rauschenberg entitled

and dated 1953.

[Emphasis added because, WTF engraved metal label?] When did it have a metal label?

There wasn’t one in 1991 when I saw it. And there wasn’t one in 1976, when Walter Hopps wrote this catalogue entry: “He [Rauschenberg] then hand-lettered the title, date of the work, and his name on a label and placed the drawing in a gold-leaf frame bought specifically for it.” [Oddly, the only source Hopps cites is an Interview Magazine Q&A, dated May 1976, just as the catalogue was being produced.]

There is no way that the hand-drawn label in the middle of the mat of Erased de Kooning Drawing could be mistaken for a metal label on a frame. At least if you had seen the work in person. Or had discussed it with anyone who had. So the implication, then, is that in 1982, Benjamin Buchloh had not actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing, or that he’d misremembered it or misread a photo of it, and neither he nor anyone at the magazine of record noticed the error. Which does make some sense if Erased de Kooning is a conceptual work in the mode of Joseph Kosuth, not an art object, per se but an “idea of an art work [whose] formal components weren’t important.” [Of course, Kosuth said that in 1965, more than a decade after Rauschenberg apparently already demonstrated it.]

But there are some problems here. Judging by all the registrars’ labels and notes on the back, it seems impossible that someone like Benjamin Buchloh would not have seen Erased de Kooning Drawing in the 30 years since its creation. But looking more closely, I can’t find any exhibitions dating before 1973. That’s when Susan Ginsburg’s show, “3D Into 2D: Drawing For Sculpture,” opened at the New York Cultural Center. [Ginsburg was, among many other things, a board member of Change, Inc., an artist emergency assistance foundation Rauschenberg started in 1970.]

Was Erased de Kooning Drawing shown in the 60s? Or the 50s, for that matter? Where? How? What was the reaction? Because the triumphant Conceptualist historicization of the work seems to have obscured–if not actually erased–its early history.

‘One Of The First Works That They Made After Becoming A Couple’

In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961, Art Institute of Chicago

I’ve had a jpg of Jasper Johns’ 1961 painting, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara on my desktop for months now. It was one of the most important works in the National Portrait Gallery’s “Hide/Seek” exhibition, and I took the chance to study it up close several times throughout the run of the show.

I have also been a little wary to write much about it, and its seemingly powerful resonance with Johns’ Short Circuit flag, partly because I was unsure of how much to read in, and how relevant or not the associations I was seeing really were.

In Memory of My Feelings definitely relates to the other, larger Flag–at 40×60 vs 42×60, it’s nearly identical in size. But unlike the 1955 Flag, or any other flags, it’s made of two canvases hinged together. Hinges, functional and not, are just one unexamined element that appears in both Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s early work. [Light bulbs are another. Maps, just barely.]

When In Memory is discussed, the somber, grey tones come first. Then there’s Johns’ stenciled inclusion of the words “dead man” next to his own name on the bottom. And the overpainted skull that you can barely make out in the upper right quadrant somewhere. And that’s it, and then the Frank O’Hara reference takes over, and the irony that Frank O’Hara would die five years after this was made–as if this had anything to do with the painting, or Johns’ painting of it.

And so I wondered why I couldn’t find anyone talking about what IS clearly visible through the overpainting in the lower right section [detail above], which is a series of vertical red and white stripes. A flag. Or maybe two. Photos weren’t allowed in NPG exhibition, and I can’t remember now. But there is at least one flag painting under there.

One person who does talk about In Memory of My Feelings, though, is “Hide/Seek” co-curator Jonathan Katz. In a gallery talk video, Katz talks about putting Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s works side by side to show it for the first time in the context of their relationship, and particularly their breakup.

Katz talks matter-of-factly about these artists’ relationship and collaboration in a way that no curator ever has. And keeping the bitterness of the breakup in mind certainly brings a lot of content to the fore in Johns’ painting. It feels especially necessary for understanding why Johns might have chosen to reference this poet and this poem. [Spoiler: it’s about dealing with the despair of a breakup.]

But Katz, whose delivery is slick and precise, not a word out of place, drops what I think is a bombshell? And just keeps on going:

When [Johns] and Rauschenberg met, one of the first works that they made after becoming a couple, was the famous–even iconic–Jasper Johns American Flag painting. This is a picture of that flag, in grey, reversed. The obverse of the picture that they made when they got together.

In one sense, it’s obvious, and in another, it’s ridiculous. Or at least unheard-of. Yes, definitely unheard-of. Katz is proposing, in passing, fundamental changes to the understanding of bodies of work, practices, and histories of two of the most important artists of the last 100 years.

This is the compelling thing for me about Short Circuit, an early 1955 Rauschenberg combine with a Jasper Johns flag behind a hinged door. A work which was originally/also titled Construct with J.J. Flag, and which was exhibited by Alan Solomon under both their names in 1958. It makes the otherwise incredible, even shocking assertion that Johns and Rauschenberg collaborated and made some of their most important work together seem perfectly obvious.

Mister Rauschenberg’s Neighborhood

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Did I say partner? I guess I meant neighbor. Here’s Christie’s quoting Paul Schimmel from his 2005 Combines exhibition catalogue:

While Rauschenberg’s work does respond to the painterly traditions of the 1950s, it does so in a manner that isolates the act of painting from the complete composition. For him, painting became a thing, an object treated similarly to Assemblage in which elements were organized on a non-hierarchical surface. Rauschenberg took aspects of Picasso and the Cubist collage, Kurt Schwitters, and the Surrealism of Joseph Cornell and created a three-dimensional, collage-based art. Together with Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg defined the American art of the 1950s; Pop art would have been inconceivable without their respective breakthroughs. Incidentally, many of their most important advancements were devised when they were most closely associated, living as neighbors, during the second half of the 1950s-the period during which The Tower (1957) was created.

[emphasis added for salient points regarding Short Circuit and for WTF, respective? Incidentally? Neighbors??, respectively.]

Schimmel goes on to note that the appearance here of a broom “anticipates Jasper Johns’s use of the broom in Fool’s House (1962), at a time when they were no longer neighbors.” Yet while he notes that “Lights and bulbs,” one of the defining elements of The Tower, “recur in numerous works”–of Rauschenberg–the fact that just months later, while they were still, uh, neighborly, Johns chose a light bulb as the subject of his first sculpture goes completely unmentioned.

Light Bulb (I), 1958, Jasper Johns, image: mcasd.org

Here is Post-War & Contemporary Deputy Co-Chair Laura Paulson in a gallery talk video,

The Tower is very autobiographical, using found imagery, found objects that would give you clues to aspects of Rauschenberg’s life. Rauschenberg was a gregarious, outgoing, very generous person, but he spoke often in sort of cryptic, very defined ways. And in Tower you have this sort of personage, which to me is just so perfectly Rauschenberg, you really feel this inside/outside aspect of it. And to me, that really defines how his art was: very autobiographical, giving you clues, but not necessarily the full story.

You don’t say.

It’s a little bit funny. One reason I’ve stayed so interested in Short Circuit has been the implications of finding the original Jasper Johns Flag on the creation myth of Flag itself. Because really, what would it mean if Johns’ first flag painting was actually shown inside his boyfriend’s combine? And he didn’t even get credited for it? What if Johns’ idea to paint the flag came from the same place as his idea to paint the map, Rauschenberg?

But what if it goes both ways? The Tower, Schimmel writes, dates from “the middle of Rauschenberg’s Combine period, which extends roughly from 1954 to 1962.” Which is, incidentally, also the period Johns and Rauschenberg were a couple. What if combines came from Johns? Or silk screening?

Or maybe it’s not so simplistic or binary. Maybe “their respective breakthroughs” were collaborative? Maybe they talked through and worked through “their most important advancements” together? How does Target with Plaster Casts relate to the combines of 1955? Or how do the combines relate to Johns’ object-laden paintings of the post-breakup era? What do the famously autobiographical, emotionally-charged-yet-obdurate works of these two artists reveal about each other, their life together, their production, and the culture in which they lived?

For three generations now, the art and art history worlds have been arguing for the separation of these two artists and the distinct, unknowable power of their “respective” achievements. Some day maybe we can tell the full story.

Lot 28, The Tower, 1957, est. $12,000,000-18,000,000 [christies.com]

From Jasper Johns’ A History Of Orgies

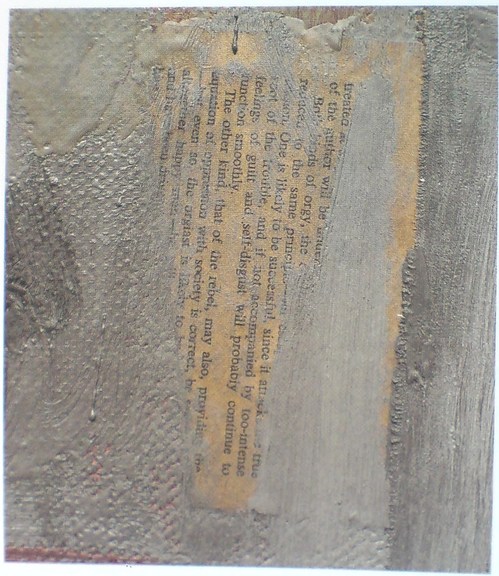

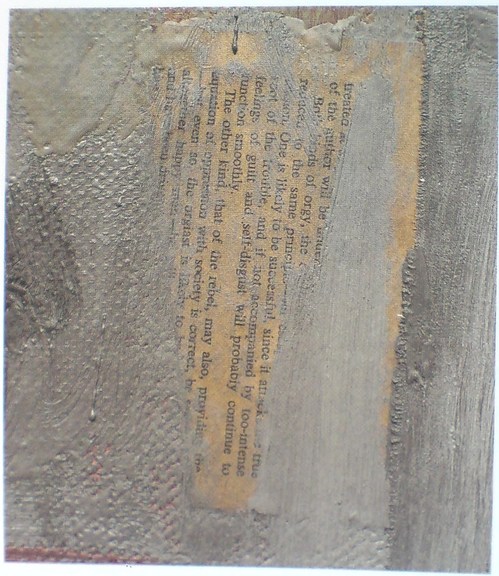

Barbara Rose called this partially obscured page of text “The most tantalizing fragment” visible in Jasper Johns’ 1962 painting, Map, and speculated that it was “probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio.” The visible word “rebel” resonated with Rose’s idea that Map is akin to a battlefield map, and relates to the Civil War, the centennial of which was being commemorated when Johns, who had recently decamped for his native South Carolina, made the painting.

It turns out the page is from the short, 2-page preface to a hardcover, the 1960 US edition of Burgo Partridge’s 1958 book, A History of Orgies. I bought this book, which is basically one Oxford student’s quick tour through the dirty parts of the classics, followed by a brief history of sexual excesses and hypocritical moralizing in Europe, ending with a call to keep pushing modern society toward a Greek ideal of a sensible, guilt-free sexual culture.

A History of Orgies was apparently a good-, if not best-, seller, both in the UK and the US. After buying a copy online–strictly for research purposes, you understand–I skimmed through it. What I don’t know about orgies could fill several books, but its argument, even its thesis, frankly, seems a bit scattershot. Perhaps more lucid syntheses of orgies have followed Partridge’s? I’ll wait for the orgiast literati to chime in. But it was impossible for me to read the preface without thinking of it in terms of Johns’ work, and also his life in 1960-62, and the culture around him.

Rose calls the visible phrases “chosen and deliberately revealed,” and says they “participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter,” which is a kind of hilarious image, given the actual source of the text.

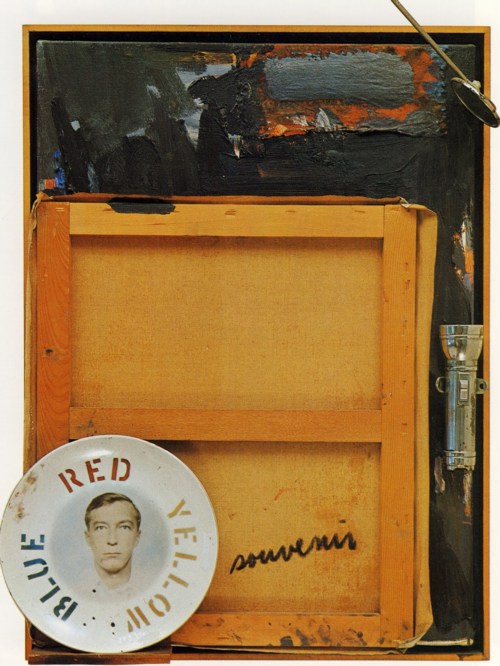

And just as the brushstrokes teasingly obscure some of the text, I also can’t help wondering what’s behind, what we can never see: the other side of the page. There are at least three Johns works from this period–Canvas (1956), Fool’s House (1962), and Souvenir 2 (1964, below)–where the artist affixes smaller canvases face down on his larger work, depriving the viewer of knowing what lies underneath. I have no idea if there’s anything in the first page of Partridge’s preface that Johns wanted to not-show, but the full text of what he ended up not-showing is below.

Souvenir 2, 1964, which was in the Ganz collection until 1997 excellent discussion at Christie’s

In the previous post, I referenced the skepticism, voiced by Yve-Alain Bois, of the usefulness of identifying [and thus being tempted to interpret] all the raw materials in Rauschenberg’s combines. It’s not like there’s a unifying, hidden message, a Rauschenberg Code, waiting to be deciphered by some future Tom Hanks. But technology is rapidly making the once-impossible trivial, and art from the past is going to have to deal with it. It took me only a couple of Googling minutes to identify a text that Rose could only speculate on–and which Johns, if he ever meant for it to be identified, has certainly not discussed.

But this impact of instant, ubiquitous information reminds me of how Land Art, once intended to be remote and highly inaccessible, if not impossible to find, ends up on GPS systems and Google Maps. The times, they’re a-changing.

Anyway, ladies and gentlemen, the preface to Burgo Partridge’s A History of Orgies with pagination intact, and the texts visible in Johns’ Map in italics:

The Orgies Of Art History

Map, 1962, Jasper Johns, via moca.org

For her contribution to the Jasper Johns Gray (2007) catalogue, Barbara Rose writes about the history and significance of Map, 1962, the artist’s first big, gray masterpiece. Johns made it to raise money for his new Foundation for Contemporary Arts, which was founded to stage some performances of Merce Cunningham. Marcia Weisman bought it out of Johns’ studio and ended up leaving it to MoCA.

Rose suggests that Johns’ Map paintings are akin to battlefield maps, and that the gray one, in fact, resonates with a particular Civil War battle, the Battle of Antietam. She cites Johns’ own South Carolina upbringing, the centennial commemoration of the Civil War that was in the news in 1960-2, and a series of paintings by Frank Stella which drew some of their titles from Civil War battlefields. [Rose was married to Stella at the time, of course, and also refers to one diptych from the series titled Jasper’s Dilemma.] Also, Rose writes, “The difficult realities of Johns’s personal life coincide with the idea that this map pictures a battlefield.”

After recounting some formalist skirmishes with General Clement Greenberg’s troops, Rose zooms in on the surface of the painting and on some of the collaged elements in Map that Johns intentionally left visible:

Topographically, the hills, ridges, and ravines of Johns’s gray Map suggest geological strata bursting. Paint washes over the surface like sea spume or waves eroding coastlines. Known borders are changed or blurred. This transgression of boundaries is a physical fact of art historical as well as personal significance. The surface is scarred and scraped in areas so that the printed matter sealed into it with adhesive encaustic is visible. The most tantalizing fragment is not newsprint but part of a page, probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio. One can make out the words “intense feelings of guilt and self-disgust,” as well as “rebel” and “orgiast.” These chosen and deliberately revealed phrases participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter.

Map detail, via Jasper Johns Gray

Lots of interesting stuff, but I am most fascinated by the overall strategy Rose adopts, of floating the connection to “the difficult realities of Johns’s personal life,” and then going both wide and deep about everything but.