I’ve been reading the transcript from Susan Weil’s interviews for the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Oral History Project. It’s four sittings over several months, so stories are retold with slight variations depending on who’s there, more Thanksgiving chestnut than Rashomon, but still interesting.

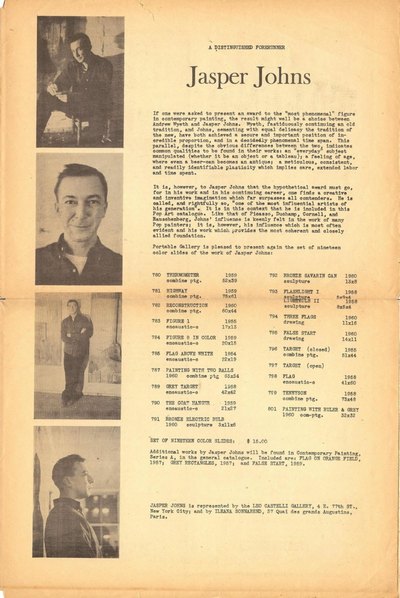

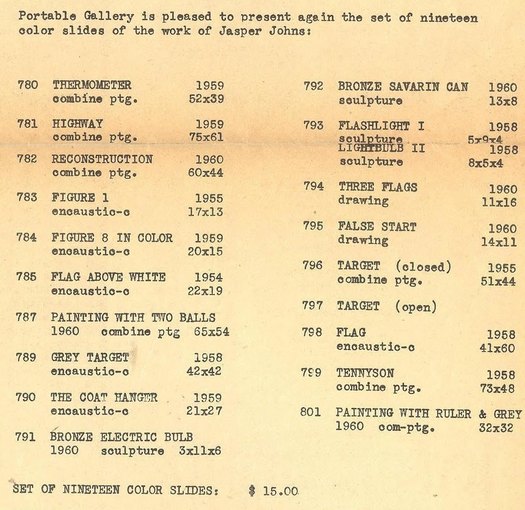

One example, in her first interview session, Weil talked about the collapse of her marriage to Rauschenberg in the Summer of 1951, just as Christopher was being born, and of the aftermath, raising him as a single parent. [Bob was at Black Mountain College during the birth, then soon took up with Cy Twombly and headed to Europe for 17 months. By 1953-4, Rauschenberg was back in New York, way downtown, and in a relationship with Jasper Johns.]:

And was Bob able to see him from time to time?

WEIL: Yes. Particularly when he was in New York, that worked out. He would see him from time to time. But Christopher, he always–they’d try to do things together, and of course at that time, Bob was really into making his art life bigger and broader. So he’d often cancel meetings with Chris, because he would have a meeting with a museum person or something.

And so Bob was supposed to take Chris to the circus, and he said, “Well, Mom, he probably won’t be able to come, because he’ll have something more important.” And I felt so terrible. And of course he did come, but Christopher had it all in his head that he was not at the top of the list.

Ouch.

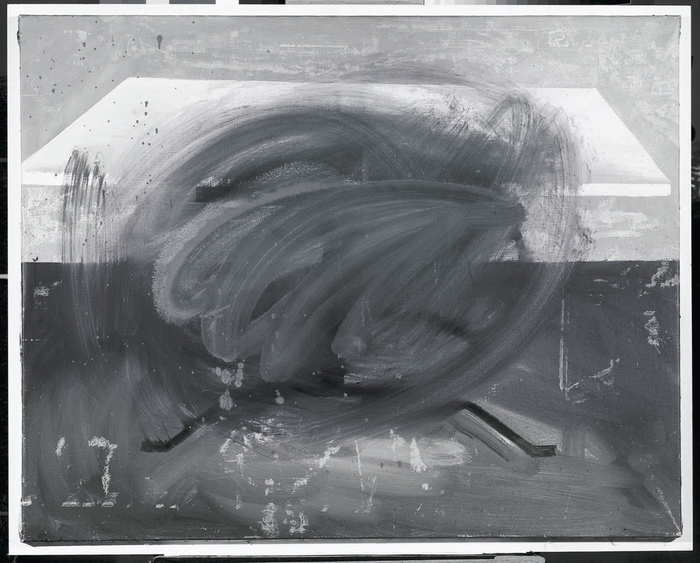

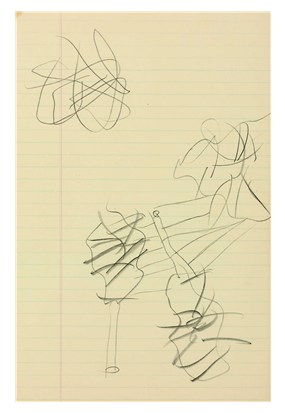

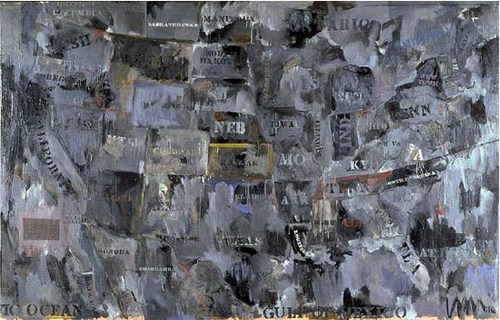

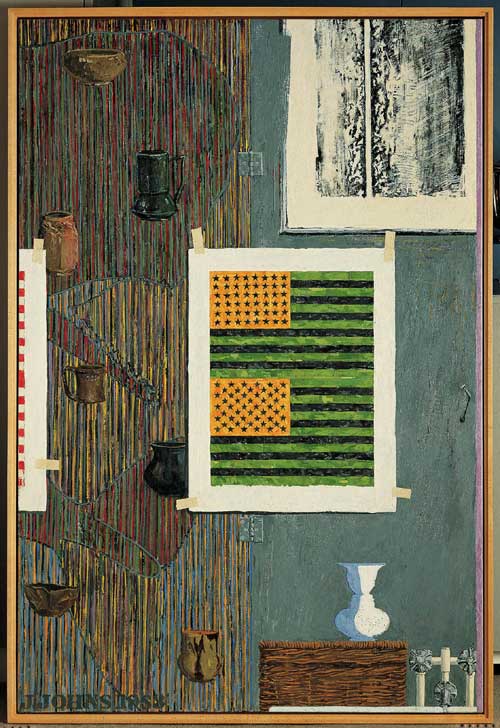

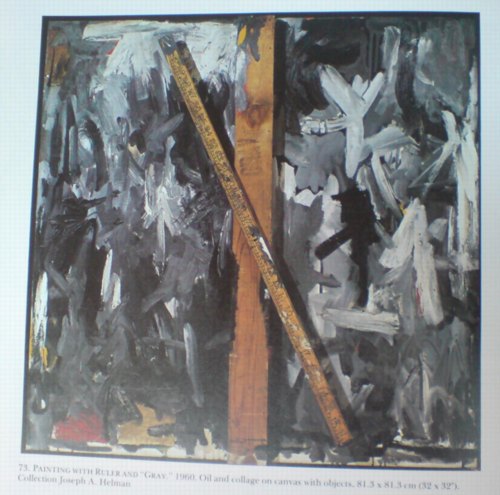

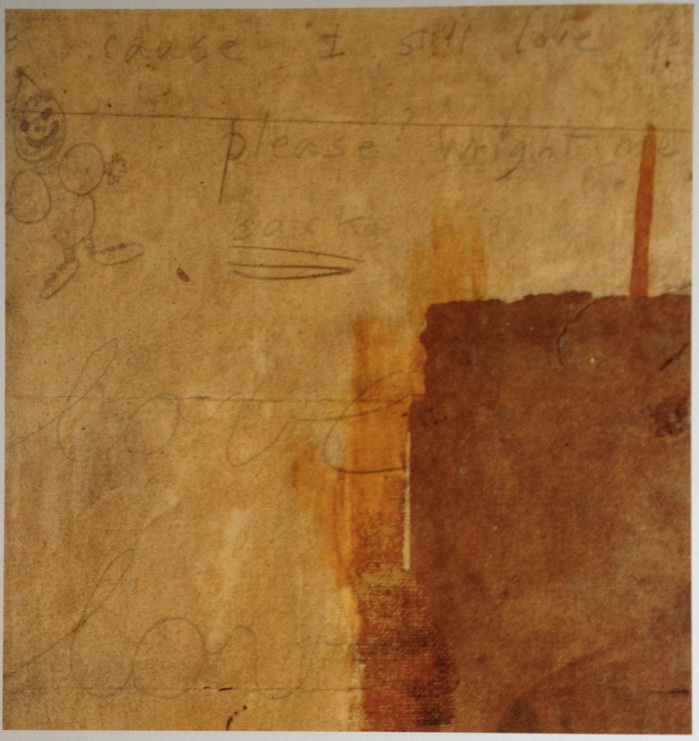

The circus reminded me of this letter, which is collaged to the face of one of Rauschenberg’s earliest combines, Untitled (1954) [above], and which was mentioned in two essays in Paul Schimmel’s 2005 Combines exhibition catalogue:

“I hope that you still like me Bob cause I still love you. Please wright me back love LOVE Christopher.” And there’s a circus clown in the corner. Same circus? Who can say? What’s notable is not whether Rauschenberg was a good dad, but that he incorporated the letter in his artwork, and how.

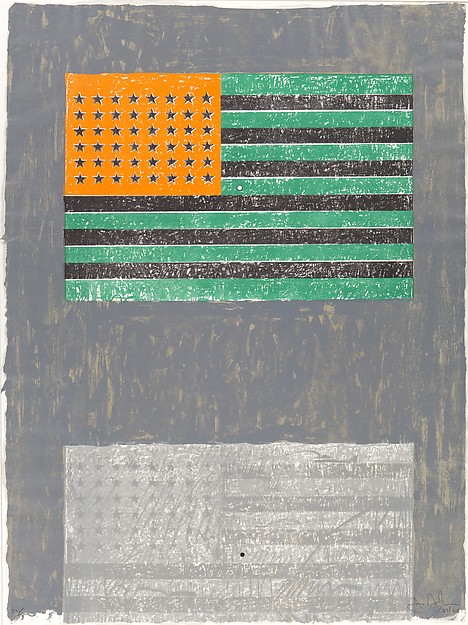

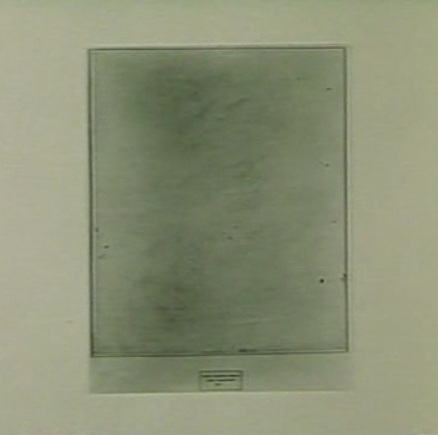

Untitled (1954-58), also called Untitled (Man with White Shoes) and Plymouth Rock, collection: MOCA, image: RRF

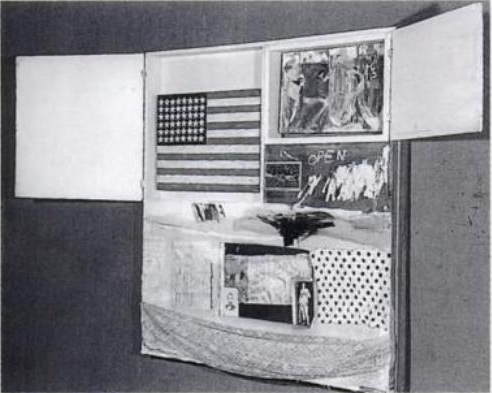

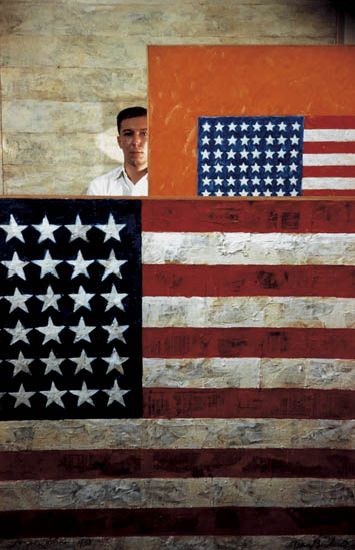

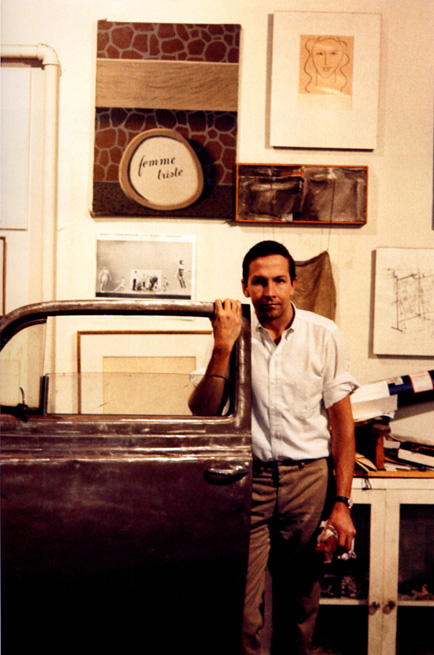

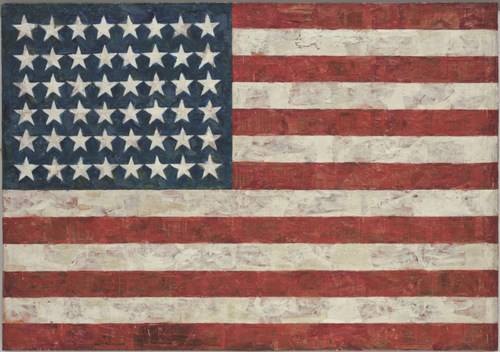

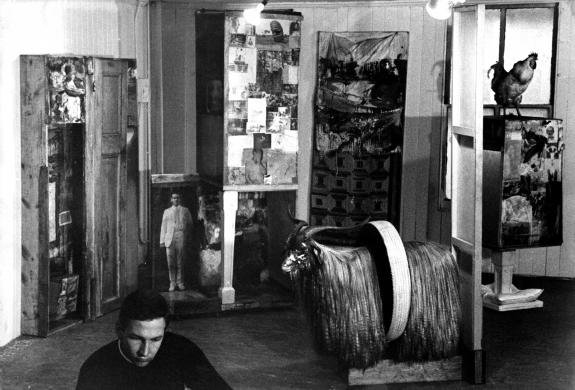

The letter is just below and to the left of an overexposed headshot of a toddler Christopher, but the handwriting is not that of a 3-year-old. Though it’s dated 1954, Rauschenberg clearly kept working on Untitled for several years. This photo of the artist’s studio shows that Christopher’s letter and photo were on there by 1958, though, the year of his (and Johns’) breakout shows at Castelli.

Rauschenberg in his Front St. studio in 1958, with various combines behind him. photo: Kay Harris via RRF

In reviewing Schimmel’s show and catalogue, Yve Alain-Bois mocked the idea of seeking insights into Rauschenberg’s combines from close readings of their collaged elements, even as he pointed out the photo of Johns and the Twombly sketch on Untitled.

When I first connected Weil’s story with Christopher’s letter, it was tragic and infuriating. Rauschenberg wasn’t busy meeting any museum people between 1954-58, he was just not seeing his son. But in Weil’s later tellings, with her son sitting alongside her, a much more sanguine version emerges; as he got a little older Christopher recalled hanging out at his dad’s and helping him make work. He was a teenage studio assistant on screenprinting, rollerskated inside, and helped unleash the turtles at E.A.T.’s 9 Evenings. In short, it got better. And in retrospect, putting his son’s letter and photo on a sculpture meant he saw it every day; Rauschenberg used his combine as the studio equivalent of the refrigerator door, sitting right in that gap between art and life.

Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project [rauschenbergfoundation.org]

Robert Rauschenberg: Combines, the catalogue from Paul Schimmel’s 2005 exhibition, is great [amazon]

Previously: The Orgies of Art History