So I sneaked out last night to see Inglourious Basterds, which I found to be generally fantastic; Brad Pitt’s craft has come a long way since Meet Joe Black.

Because, I confess, I’m still working through a stack of badly panned & scanned DVDs of lost grindhouse epics, I have fallen behind in my study of spaghetti westerns and the lesser-known works of Lee Marvin. And so I was worried that Tarantino’s many subtle, referenzia cinematografistica which so many esteemed critics alluded to might slip by me unnoticed–and if that happens, what’s the point, right?

I needn’t have worried. From the twangy, scratchy get-go, where the opening track sounded like it was being played back on Hi-Fi to mimic the apparently primitive audio post-production facilities of Italy [1], Tarantino is not shy–hah, as if–about his stylistic references.

Oh, and contrary to some opinions, I thought Mike Myers was spot-on. I’d always joke-assumed Pitt won the Travolta/Forster/Carradine/Russell casting lottery this time as the actor whose forgotten talents and fizzling career would be nobly rescued by the director fanboi who Never Forgot. But I was wrong; it’s Myers. You now have at least two years where we won’t hold The Cat In The Hat against you, Mike. Use them well.

Anyway, the point, and the thing I either overlooked or never heard, was what a big, fat, sloppy kiss to the cinema this thing was. And not just the blatant, “Make me a Cannes juror for life!” applause line [“I’m French. We respect directors in this country.”] either. I’m talking about how the whole plot is basically the basterd child of The Dirty Dozen and Cinema Paradiso.

Also, *SPOILER ALERT?* was there NOT a shoutout to the end of Raiders of The Lost Ark? Does this mean Tarantino’s officially moved onto hommaging 80s pop film now? I see Michael Schoeffling as Robert Forster.

[1] Whenever he gets around to making it, I’m sure QT’s Punjabi murder musical will sound like it was recorded in the bathtub.

Category: movies

On LACMA Killing Its Film Program [To Save It?]

Regular readers of greg.org know it, but I’ll say it upfront: I’m Team MoMA. I’ve supported the museum for years–I feel like I grew up in it, art-wise. And film-wise. Right now, MoMA’s film department and programming are stronger than I can ever remember. It feels absolutely vital, critical. And even when the old timers SHHH! people for breathing too loud in the theater, it’s great to see a movie there.

And yet the Bing theater at LACMA is even nicer. And yet, LACMA is suspending [i.e., killing] its film program. In Los Angeles. It’s just mindboggling. They have to be planning a complete, and somehow different reboot, a makeover of some kind for which Michael Govan’s only plausible path is going cold turkey.

Two home team analogies: MoMA’s Projects series, which lived for a very long time just off the lobby as a small gallery for anointing emerging artists, but which was eventually brought back to the Taniguchi building as a roving showcase for [basically] New York debuts by global artists. Generally speaking, it seems to be working.

The other is more directly film-related: the Modern caught a lot of flak for closing its film stills collection, squeezing out the longtime curator and librarian–who happened to be active in the employee’s union, and the whole thing went down around the time of the staff strike–and shipping the whole thing off to the film center in Pennsylvania. It was a controversial action, to say the least, but [film] life goes on. What the net impact is, nearly a decade later?

So yeah, I’m alarmed by Govan’s decision and by Kenneth Turan’s outrage over it. But I also have to hope that some kind of substantial film program will return, even if it’s new and different and takes a while. Because I can’t imagine otherwise.

LACMA slaps film in the face [latimes]

In The Beginning There Was Not Just Tron

So while we were staring slack-jawed at the computer graphics in Tron, Loren Carpenter had already produced and shown Vol Libre, this incredible fractal mountain flythrough animation two years earlier at SIGGRAPH–and had been hired on the spot by Industrial Light & Magic? And you’re only getting around to uploading it now, nearly 30 years later?

Vol Libre from Loren Carpenter on Vimeo.

What else you hiding, Pioneers of Computer Animation? [via kottke]

Night At The Apollo Program, Or How The Moon Is Made Of Cheese

Saturday night we went to the Kennedy Center in Washington for the National Symphony Orchestra’s commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the moon landing, Salute to Apollo: The Kennedy Legacy. It was the wackiest cheesefest of a concert I’ve ever been to.

We tried to puzzle out how a program like this came together. NASA was heavily involved, of course, and there was a mix of the nerdy with the obligatory and the available. But I have to think that the prime directive for the evening was written by NSO conductor Emil de Cou, who might be a gigantic space nerd.

The Playbill mentions de Cou’s multiple NASA colabos, including the smashing success of the NSO’s multimedia performance of Holst’s The Planets at Wolftrap in 2006, with narration written by de Cou and performed by Leonard Nimoy and Nichelle Nichols.

Three of these planets were repeated on Saturday, only instead of Spock and Uhura, the narrators were Scott Altman [commander of the last space shuttle mission] and Buzz Aldrin, who is a giant, if amiable, ham. But also a good sport, since Neil Armstrong apparently doesn’t do parties anymore. In addition to his Presidential Medal of Freedom, Aldrin wore some kind of bulbous, metallic, Airstream bowtie. We had truly excellent orchestra seats, and even the most eagle-eyed among us couldn’t figure out what had landed there around Buzz’s neck.

The Planets [“Mars,” “Saturn,” “Jupiter”] were accompanied by dramatic pans of NASA imagery on the large overhead screen. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The performance started, naturally/bombastically enough, with a gorgeous montage of Apollo 11 from Theo Kamecke’s long-forgotten, recently rediscovered and remastered 1971 feature documentary, Moonwalk One–which was cut to the theme from 2001.

2001, of course, came out in 1968, in the middle of the Apollo program, but before A11. And yet it suddenly felt inextricably linked to it, or conversely, the NASA programmers and audience themselves felt a continuity between the scientific and engineering facts of their missions and the science fictions of the time. Like how members of actual Mafia families began patterning their behavior on The Godfather. This is not some cockamamie theory, as the rest of the NSO program clearly illustrates:

Horst was followed by John Williams’ theme song to–no, not what you’re thinking, not yet–Lost in Space. Introduced on video by June Lockhart, who then made a “surprise” live appearance on stage. She was over the moon with excitement, which I took as a sign that she doesn’t do much onscreen work these days. She was thrilled to be there.

Then there was a medley of Star Trek themes, introduced on video by a funny/kooky Nichelle Nichols. She looked great. Clearly, de Cou has stayed in touch. About ten seconds into the orchestra’s intense rendition of ST:TOS, I realized I should have been recording it on my phone to use as my ringtone. But I didn’t.

Nichols didn’t appear on stage, instead the orchestra headed straight into its John Williams Star Wars medley.

Then Denyce Graves came out to sing a moon-related aria from Dvorak, which was the accompaniment to, was accompanied by–it was hard to tell–a montage of beautiful film footage of astronauts jumping around the moon and driving their moon buggies, scenes which caused the audience to erupt in bursts of laughter. Which was not funny, because the song, from Rusalka, is basically the Czech Little Mermaid singing about trading her voice for love or something.

Anyway, then Jamia came out. Never heard of her, but she’s apparently the black Hannah Montana. Then Chaka Khan came out in a Victorian bordello outfit to sing some NASA-commissioned anthem by a famous jingle composer [“You deserve a break today/ So get up and get away”]. Then the Army chorus sang “America the Beautiful” and John Phillip Sousa. I didn’t even know it had words. And then we left.

God bless America and its grandiose cheese spectacles.

On The Likelihood Of The National Gallery’s Barkley Hendrickses Ending Up In The White House, Ch. 1

The “What art should the Obamas hang in the White House?” story rolls slowly onward. Last week in ArtInfo, Ruthie Ackerman published the suggestions of several of the art world’s greatest minds. Greatest among equals, obviously, is Magda Sawon of Postmaster Gallery, whose list began,

“I am seconding Greg Allen of the brilliant blog greg.org to bring Sir Charles aka Willie Harris (1972) by Barkley Hendricks to the White House. It’s a tremendous painting from a still-under-the-radar master that puts Kehinde Wiley to shame.

Hear, hear!

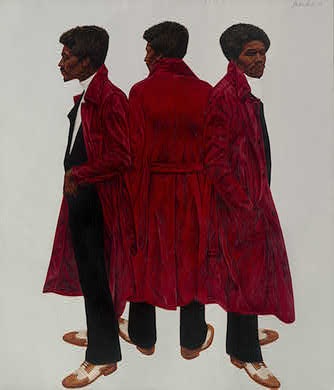

Now that we have consensus, let’s move this plan forward, shall we? The National Gallery of Art brought Sir Charles into the collection in 1973, along with another remarkable Hendricks portrait, George Jules Taylor. Neither have ever been shown in the National Gallery itself, though both are included in “The Birth of Cool,” the highly acclaimed Hendricks retrospective organized by Trevor Schoonmaker of Duke’s Nasher Museum of Art.

By the criteria the Obamas set for themselves, that means the works couldn’t come into the White House until they go back out of public view, 2010, after the retrospective winds up in Houston. Plenty of time to make the case for this awesome painting; let’s take a closer look at it!

Duke art historian Rick Powell explains that Sir Charles was the professional name of a Dixwell Avenue drug dealer in New Haven whose customers were mostly students from the little college a couple of blocks to the east, where Hendricks was studying for his MFA. The Willie Harris reference, meanwhile, is from A Raisin in the Sun; like that fictional Harris, Powell says, Sir Charles “would frequently disappear with [his customers’] money.”

Hmm, could the Obamas ever really bring themselves to hang a painting in the White House of a small-time, money-thieving, pimped out, drug dealer–from Yale??

Hendricks described Sir Charles’s style as “player chic,” which the ever-proper Powell feels compelled to address at some length:

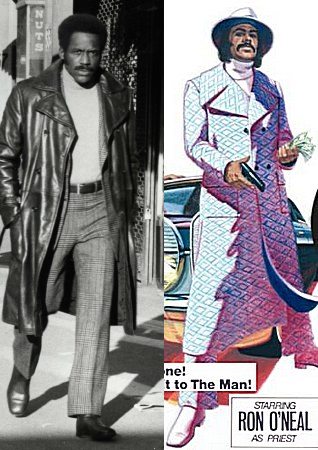

While the term “player chic,” hinting at illicitness and misogyny, points to the ostentatious fashion statements of pimps, street hustlers, and other disreputable members of a black demimonde, the same style of dress–platform shoes, body-hugging jumpsuits, leather pants and maxicoats, real and artificial fur–was worn by a broad spectrum of African Americans. Most were not connected with life’s shadier side, but many did feel an affinity for this provocative “outlaw” persona. The most obvious broad-based celebration of the “player chic” aesthetic in the early 1970s was the commercial success of Super Fly (1972), a feature-length film directed by Gordon Parks Jr., about a drug dealer who undergoes a change of heart…

Uh, not to quibble, but wouldn’t the phenomenal critical and financial success of Shaft, made in 1971 by Gordon Parks Sr., count as a broad-based celebration of player chic, too?

in which case, wasn’t the swaggering black male “outlaw” archetype thoroughly established, even romanticized in popular culture, making Hendricks’ choice of Sir Charles as a subject a little less transgressive or controversial, at least among the edgier liberal audiences at Yale and–

Wait a minute, where was Hendricks’ audience? The guy was still in art school when he painted these things in 1972, and then they were in the National Gallery a few months later? How’d that happen?

Stay tuned.

Khaan! A 23rd Century Portrait

Wow, the 2-minute clip of Daniel Martinico’s 15-minute Khaan! is fantastic. This is more what I thought Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s Zidane would be like, but wasn’t.

LA Weekly review from a 2008 screening [laweekly via boingboing]

Bueller!!

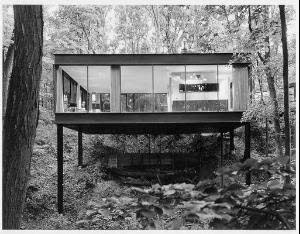

OK, why did no one tell me when I posted about A. James Speyer’s awesome-but-maybe-never-realized Miesian Adirondack cabin that the Chicago architect was responsible for the most important Glass Box-in-a-Forest of the entire 1980s?

Of course, I’m talking about Cameron’s house in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which just went on the market for $2.3 million. [realtor.com, or try cinematical when that one expires]

This Poeme Electronique Was Brought To You By Philips

Hello, Earth to Le Corbusier archive!

Corbusier conceived Poeme electronique for the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Expo in Brussels. It was an 8-minute immersive light, film and sound experience which told mankind’s long, hard slog towards peace.

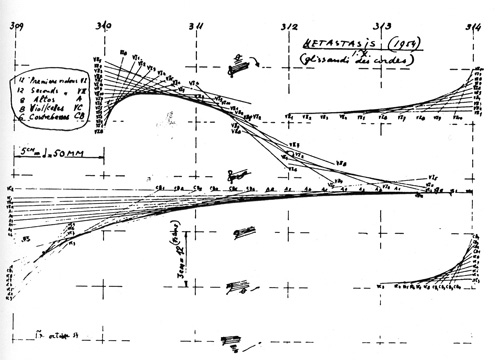

Don’t forget the architecture. The multi-channel version of Poeme electronique, with a score by Edgard Varese, was projected on the walls of the tensile tent-like pavilion, which was designed by composer/architect Iannis Xenakis, who was working for Le Corbusier’s firm at the time. Xenakis recalled–perhaps wishfully, I don’t know–that the parabolic concrete forms came directly from his graph-based score for his 1954 composition, Metastasis. [The piece was staged last March at the Barbican as part of a Xenakis program, concurrent with the Corbusier exhibition.]

Here’s Poeme Electronique in its single channel version:

This brief segment produced in 2000 for a virtual reality recreation of the Poeme Electronique experience also includes period footage, photos, and a couple of interesting looking models from the Philips archives:

Le Corbusier; Iannis Xenakis; Edgard Varèse

«Poème électronique: Philips Pavilion» [mediaartnet.org via things]

previously: E.A.T. and the Pepsi Pavilion, Osaka Expo 70; a lost piece of corporate-sponsored installation art?

Holy Smokes, New Yorker Films Is Closed

I can’t believe it. New Yorker Films is closing after 43 years in the independent and foreign film distribution business. In the business? They were the business for decades.

When I was working the projection booth at International Cinema at BYU, it was New Yorker’s library I was soaking in. When I moved to New York, it was Dan Talbot’s Lincoln Plaza Theater [and the Angelika, which I discovered on its inaugural weekend during a senior year road trip] where I saw most everything since.

New Yorker was sold to Madstone Films in 2002, and that company pledged New Yorker’s library as collateral and then defaulted on the loan. The creditor, which may be Technicolor, initiated foreclosure proceedings last week. For the sake of the 500+ classic title library, at least, I hope it’ll get acquired by someone who knows Ozu from Oshima. For the sake of Dan Talbot and his colleagues, I can only hope for a soft landing and many thanks.

End of the Road for New Yorker Films [indiewire]

Kim’s Video To Reopen In Salemi, Sicilia

The first time I finally dared go into Kim’s video, I thought I was ready, so I asked why Blade Runner wasn’t in the Ridley Scott section. [Yes, son, back when I was a boy, we had to go all the way to St Marks to rent Blade Runner. Uptown both ways.] Anyway, the clerk scoffed, “Because it’s in the Douglas Trumbull section.”

Now the Times has an awesome story about how it came to pass that Kim’s entire collection of 50,000 films, passionately collected from around the world, will become the centerpiece of an art town being organized in an abandoned hilltop village in Sicily.

I count this as a huge win. I will go to Kim’s Salemi ten times before I ever even think of heading to the Village to rent a VHS tape.

La Dolce Video [nyt]

Wait, Where’d Stars Wars A Capella Guy Go?

Why is Corey Vidal’s YouTube account suspended? The guy who did the lip synch video for Moosebutter’s “Star Wars A Capella” which was seen by over 3 million people, and which was nominated for a People’s Choice Award [it lost to Barack Roll] has had his entire YouTube account suspended. The notices say there was a terms of service violation. The Star Wars A Capella video itself was removed “due to a copyright claim by WARNER MUSIC GROUP.”

On Moosebutter’s blog yesterday, they posted this message:

Star Wars video, how we miss you…

moosebutter has finally gotten attention from a major music company!

Unfortunately, it came in the form of pre-emptive legal action.

Corey Vidal and our Star Wars videos were taken down by Warner Music Company, or Warner Brothers, or Warner INC … all we know is, Warner has gotten picky about ‘their’ content on youtube, and even though there are a dozen other videos on youtube with our Star Wars song, and hundreds of videos that illegally rip footage from Harry Potter DVDs, and fake Batman trailers and etc etc etc Warner has been kind enough to target our stuff.

This means one thing: we’ve finally hit the big time! Maybe.

So, we apologize about the videos being gone, but the youtube powers are looking into it, so we hear.

We also believe that the music will still be sold from our web site, since we think we’ve done everything legally… but we thought the youtube videos were legal, too. So, buy the mp3 now before it gets taken down! Hooray!

Vidal’s video brought a massive new audience to Moosebutter’s song–and recording–after YouTube featured it on their front page, but the song itself is almost ten years old, and Moosebutter have been recording and performing it since at least 2000.

And it’s more than a bit confusing what their actual claim is. One of the six John Williams soundtrack melodies in the composition, Superman, is from a Warner Brothers movie, though Warner Music is making the claim, so maybe they distributed this or some of the other soundtracks. But “Star Wars A Capella” seems like a classic example of transformative, not derivative use, exactly the kind of thing that should be allowed under fair use as a parody.

If the sampling industry’s current practice is applied, however, Moosebutter’s use of the core melodies of each song–the whole point/genius of their Williams tribute composition is that the sources are all instantly recognizable to moviegoers–the song is an infringement from beginning to end. Only they didn’t use recordings, but compositions [and dialogue, which almost all comes from Star Wars episodes.]

Whatever the claim, this court finds Warner to have made a dickheaded move.

“An Unannounced Preview At The Coronet” Of Pasolini’s Teorema

From Vincent Canby’s April 22, 1969 review in the New York Times:

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Teorema,” which opened yesterday at the Coronet, is the kind of movie that should be seen at least twice, but I’m afraid that a lot of people will have difficulty sitting through it even once. At least there were some who had that problem Friday night when the film was given an unannounced preview at the Coronet, supplementing the regular program, headed by “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.”

It was a disastrous combination. “Baby Love” is a straightforward, skin-deep narrative movie that elicits conventional responses to familiar stimuli. “Teorema” (theorem) is a parable, a movie of realistic images photographed and arranged with a mathematical precision that drains them of comforting emotional meaning. For the moviegoer whose sensibilities have been preset to receive “Baby Love”–or just about any other movie now in first run here–“Teorema” is likely to be a calamitous and ridiculous experience.

…

There is very little dialogue in the movie–923 words, say the ads (but I’m not sure whether this refers to the Italian dialogue or the English subtitles). Even though Pasolini is a talented novelist and poet, the film is almost completely visual. The actors don’t act, but simply exist to be photographed. The movie itself is the message, a series of cool, beautiful, often enigmatic scenes that flow one into another with the rhythm of blank verse.

This rhythm–one of the legacies of the silent film, especially of silent film comedy–was impossible for the Coronet audience to accept. The seductions are ticked off one after the other with absolutely no thought of emotional continuity. So are the individual defeats, which are punctuated by recurring shots of a desolate, volcanic landscape swept by sulphurous mists.

There is also a kind of rhythm within the images. Someone seen in right profile is immediately repeated in left profile. An action that proceeds to the left across the screen may be switched 90 degrees, directly away from the camera, or into the camera. Early scenes are in black and white. Later scenes are so muted they almost look like the old Cinecolor process, only to go monochromatic again at the end.

Can you imagine a theater today showing an unannounced preview after the feature? Or showing Pasolini at all? I still have a raincheck ticket in my wallet from the Coronet [aka the Baronet Coronet, aka the Coronet I & II, which was demolished to make way for an Urban Outfitters] to go back and see Dancer In The Dark. I went to a noon showing, only to realize I was crazy and had a call at like 2pm, so I left before the trailers ended. Oh wait, I just pulled it out. The ticket was from the Cinema 1,2,3,4 up the street. Never mind. The Pasolini thing’s still crazy, though.

Theorem (1968) The Screen: A Parable by Pasolini: Teorema’ in Premiere at the Coronet Terence Stamp in Role of a Visiting God [nyt, via sal mineo’s ghost, thanks ready for the house]

Star Wars Toasted, With Extra Cheese

I know there’s really no other way for Lucas & co to justify the existence of a Darth Vader Toaster than to just embrace the idiocy and hang on for dear life, but still. Holy smokes:

If there’s something every Sith Lord knows how to do it’s make a balanced breakfast. While the Jedi have to live off of Jawa juice and fried nerfsteak, the Dark Lord of the Sith prefers to have a reminder of his fiery Mustafar defeat at his breakfast table. Every morning he burns that moment into a slice of bread with the Darth Vader Toaster. This black, ominous kitchen appliance easily leaves the mark of Vader’s helmet in every yummy piece of toast. Slather some Bantha butter on top, or make two pieces for an extra-Sithy BLT. Force power not required to operate toaster.

I imagine the $48/toaster gross margin helps ease the conscience as well.

Darth Vader Toaster, $54.99, pre-order for Jan. 2009 delivery [starwars.com via c-monster]

Bruce Willis Type For President?

Two essays, each interesting and thoughtful on its own, crossed my desk this morning. I think they’re inter-related.

First from the always spatially aware Geoff Managh on the seemingly irrational landscapes of presidential campaigning:

…President Bush had stopped off this morning to speak about the credit crisis “with consumers and business people at Olmos Pharmacy, an old-fashioned soda shop and lunch counter” [1] in San Antonio, Texas.

The idea here – the spatial implication – is that Bush has somehow stopped off in a landscape of down-home American democracy. This is everyday life, we’re meant to believe – a geographic stand-in for the true heart and center of the United States.

But it increasingly feels to me that presidential politics now deliberately take place in a landscape that the modern world has left behind. It’s a landscape of nostalgia, the golden age in landscape form: Joe Biden visits Pam’s Pancakes outside Pittsburgh, Bush visits a soda shop, Sarah Palin watches ice hockey in a town that doesn’t have cell phone coverage, Obama goes to a tractor pull.

It’s as if presidential campaigns and their pursuing tagcloud of media pundits are actually a kind of landscape detection society – a rival Center for Land Use Interpretation – seeking out obsolete spatial versions of the United States, outdated geographies most of us no longer live within or encounter.

…

All along they pretend that these landscapes are politically relevant.

Then there was Matthew Dessem’s perceptive and awesome explication of The Criterion Collection’s seemingly inexplicable inclusion if Jerry Bruckheimer and Michael Bay’s 1998 oil-drillers [!] turned-astronauts-save-the-world disaster epic, Armageddon–which quotes the much-missed David Foster Wallace:

Critics who thought Armageddon was a sort of terminal end point for filmmaking (which is to say, all of them except David Edelstein, as far as I can tell) missed the point. Janet Maslin, for example, wrote, “Armageddon tries to tell a coherent story of guts, young love and space travel.” But I don’t think it does try; it’s not really interested. You wouldn’t criticize Star Tours or Batman: The Ride for shoddy characterization or wooden acting, and it doesn’t seem fair to me to treat movies like Armageddon as though their writers and directors had the same goals as, say, Tarkovsky. David Foster Wallace put it best (in “David Lynch Keeps His Head”):

Art film is essentially teleological; it tries in various ways to “wake the audience up” or render us more “conscious.” (This kind of agenda can easily degenerate into pretentiousness and self-righteousness and condescending horsetwaddle, but the agenda itself is large-hearted and fine.) Commercial film doesn’t seem like it cares much about the audience’s instruction or enlightenment. Commercial film’s goal is to “entertain,” which usually means enabling various fantasies that allow the moviegoer to pretend he’s somebody else and that life is somehow bigger and more coherent and more compelling and attractive and in general just way more entertaining than a moviegoer’s life really is…

…

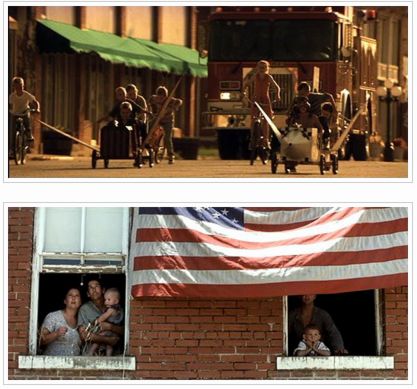

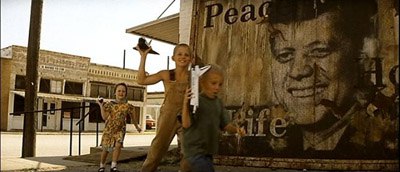

The level of personal wish fulfilment in Armageddon is pretty easy to pick out; it’s worth noting that Michael Bay also sells a kind of national wish fulfilment. Armageddon has a serious hard-on for the early days of the space program, specifically for the sense of national purpose it gave the country. In fact, the movie suggests that that America, that national conception of ourselves, is still pretty much what we are, as you can see below.

In case you miss it, this shot is immediately followed by one of the astronauts saying “Kennedy, we see you. And you never looked so good!” Of course, he’s talking about the Kennedy Space Center…or is he? The point is, these sections are shamelessly manipulative and there’s nothing delicate about them. Nevertheless, they have an elegiac tone that’s more moving than anything else in the movie. And they seem motivated by a genuine longing for a national purpose, and national heroes, for a more innocent version of America. Of course, that America never really existed, and Armageddon offers Bruce Willis as just the sort of national hero we’re looking for, but hey, you take your pleasures where you find them…

Which makes me think that complaining about the irrelevance of political space is like critiquing the incoherence and narrative of Armageddon. The landscapes of the American political blockbuster are designed to provide wish fulfillment and a sense–however fictional or misguided–of “national purpose”–and ultimately, of a “national hero.”

As this remarkable montage of the US president [2] addressing the world shows, the common landscape of Armageddon‘s politics is the flat, square–and as Dessem points out, time zone-free–space of the television screen:

Minor Landscapes and the Geography of American Political Campaigns [bldgblog via city of sound]

#40: Armageddon [criterioncollection via goldenfiddle]

[1] as the photo shows and a bldgblog commenter points out, Olmos Pharmacy has actually been reinvented as Olmos Bharmacy, “a combination soda fountain counter and wine bar.”

[2] For a second I was worried, but then I realized that it was the other 1998 space-object-destroys-the-earth movie, Deep Impact that had the black president.

More Beckett On Film, Or Stop-Action Animated Video, Anyway

Awesome. a Lego Mini-Fig interpretation of the first scene of Beckett’s “Endgame.” The grandparents are just hilarious. [youtube via choire]