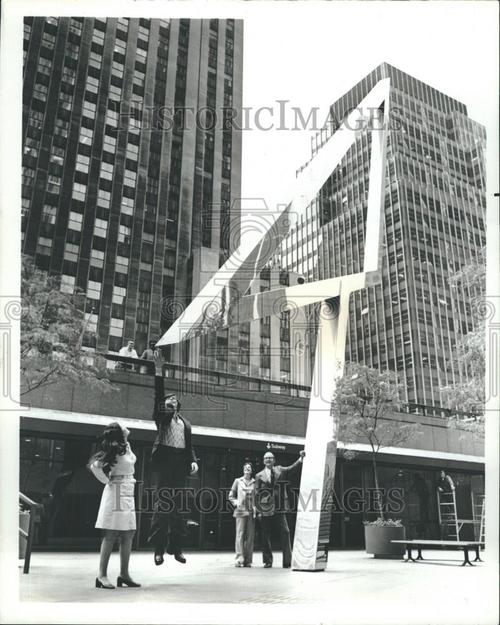

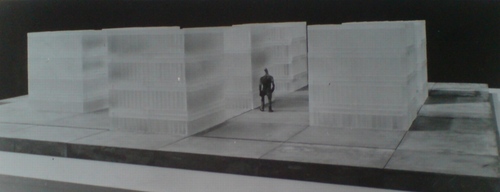

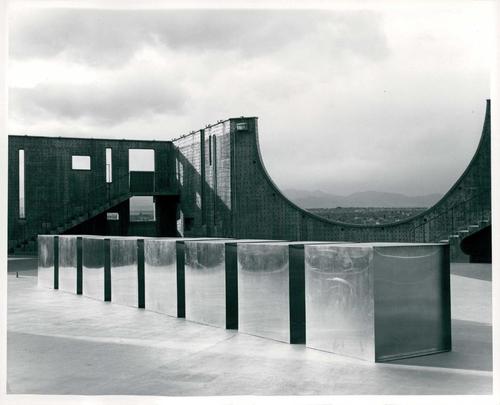

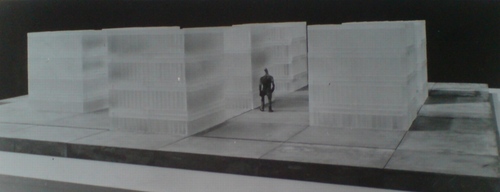

I recently came across this photo of Louis Kahn’s “Monument To The Six Million Jewish Martyrs,” which, I had no idea. And it was to be built in New York City, Battery Park, to be exact, and was perhaps the last best chance for an apparently serially disastrous effort to build a Holocaust memorial in the city. Ultimately, of course, the city did get the Jewish Memorial Museum in the 1990s, in Battery Park.

There is no doubt a story to tell about the tumultuous history of that process. And I’m sure someone has already written a decisive history of how people attempted to grapple with the Shoah and Holocaust as history, and how and when those concepts took hold. Because they’re absent from the contemporary discussion of this memorial. But what really sticks with me is the story and particulars of Kahn’s memorial design, and how resonant it seems with memorials followed it.

Kahn was recommended by an Art Advisory Committee [via Philip Johnson] that had been brought in in 1966 to help the Committee to Commemorate the Six Million Jewish Martyrs solve their seemingly impossible charge: creating a suitable memorial to genocide. The NY Times’ architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable complained that the previous designs were full of “wrenching angst” in which “the agony and the art were almost too much to bear.”

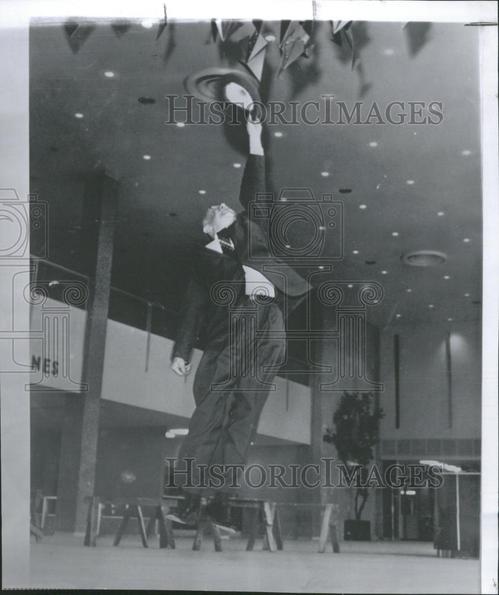

After the City Art Commission approved it, Kahn’s 6-foot model was put on impromptu display in the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art for month, from Oct-Nov. 1968. Which is when Huxtable praised as architecture and sculpture “of the highest order”:

In an age that has made a flat mockery of conventional memorial values and platitudes, Mr. Kahn’s solution is a cool, abstract, poetic, powerful and absolute statement of the unspeakable tragedy. It could rank with the great works of commemorative art in which man has attempted to capture spirit, in symbol. for the ages.

And in case you needed any more reminder that memorials are as much an expression of the time they’re created, not just the history they mark, here’s Huxtable’s final judgment:

The generation that lived through the time and events the monument proposes to commemorate will never forget them. We have that memorial seared in our souls.

The generations that are innocent of this kind of totalitarianism and ultimate tragedy will find no monument meaningful. That is one of the anachronisms of art and history in an age of violence.

This memorial could work, as art and as history, and as a lasting expression of the human spirit. In a nihilistic, value-destroying society, that is no mean artistic accomplishment.

Yow, no Summer of Love here.

Kahn’s Monument was to consist of seven 10×10 squares, 11 feet high, made entirely of elongated, cast glass brick, and arranged 2-3-2 on a 66-ft square grey granite plinth. [His original design, presented to the Committee in 1967, called for nine 12x12x15 squares in a grid. I think the switch to 6+1 was a way to Judaize and particularlize the memorial’s content.] The translucent bricks meant that the blocks would change with light, weather, and the presence and movement of people around the site. Only the center cube would be inscribed and accessible; as Kahn put it, “The one, the chapel, speaks; the other six are silent.”

I think Kahn’s 1967 proposal is at least one of the earliest, if not the first, deployments of Minimalism in a memorial context. Or maybe Post-Minimalism is more accurate, since Kahn’s evocative forms and their deliberate emotional and experiential evocations were anathema to the objective Gestaltism of orthodox Minimalism as it was being argued out at the time.

If the history of using a Minimalist formal vocabulary for intractable memorials typically began with Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial, then Kahn’s Monument pushes it back 15 years–to the conflict-torn heart of the Vietnam era. And though it wasn’t realized as he envisioned, Kahn’s proposal was influential. It’s the best explanation I can see for for the use of glass block in New York State’s disappointing Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Water Street in lower Manhattan. [That memorial’s plaza siting was probably also influenced by Huxtable’s unequivocal condemnation of the Battery Park site for Kahn’s memorial, an insurmountable criticism which probably doomed the design she praised so highly.] More directly, though, Kahn seems like a direct progenitor for the two most prominent Holocaust memorials built in Europe to date.

Kahn’s formal references to the silenced, the room-scale, and the bookshelf-like bands of glass brick are all echoed in Rachel Whiteread’s Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial, where a ghostly library of books the city’s murdered Jews will never write stands on a plinth in a public square in Vienna. Whiteread’s memorial has obvious precedents in her own sculptural practice, and I’ve never seen her mention Kahn as an inspiration, so it’s entirely possible that these resonances are natural and widely held, and which the artist and architect arrived at separately.

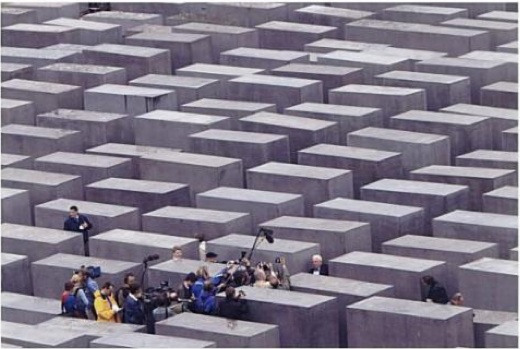

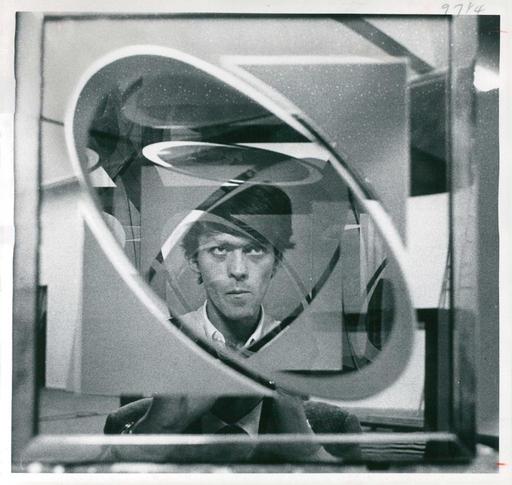

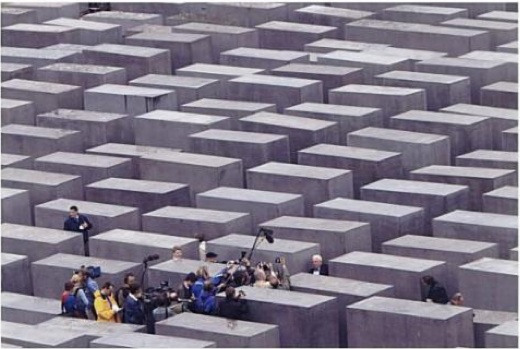

Amazing shot of Peter Eisenman at the 2004 opening of his Berlin Memorial from Mark Godfrey’s book, Abstraction and The Holocaust

I can’t believe that’s what went down, however, with Peter Eisenman and Richard Serra. From its central formal device–passages between impenetrable, figure-dwarfing blocks–to its title, Memorial to the Six MIllion Murdered Jews of Europe, Eisenman and Serra [who subsquently removed his name from the project] had to have been very familiar with Kahn’s proposal, and with the politically fraught development process that spawned it.

Oh, look, Mark Godfrey’s 2007 book Abstraction and the Holocaust has an entire chapter on Kahn’s Monument. [amazon, google books]

Anthony Vidler wrote about Kahn’s memorials [cooper.edu]

The Louis Kahn Collection at UPenn has drawings and a different model of the memorial. [upenn.edu]