One of the most incredible works of visionary art in Washington DC is James Hampton’s The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation’s Millennium General Assembly. Hampton, an African American WWII veteran and janitor at the General Services Administration, built the 180+piece assemblage out of discarded furniture, cardboard, cellophane, blotter paper, and foil, in a rented DC garage. He spent at least 14 years working every night, in secret, and it was only discovered by his landlord after his death in 1964. After several uncertain years, it was donated to the Smithsonian’s Museum of American Art in 1970.

Hampton told almost no one about his work, but notes attached to the various objects seem to indicate that he was receiving visitations by angels, who directed him to construct the Throne in preparation for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. Most of the notes, though, and his voluminous writings, as well as the contents of a looseleaf notebook titled, The Atlas of The State of Eternity, are written in Hampton’s own code, which is comprised of mixed and altered Hebrew, Greek, and Roman characters. As far as I can tell, these works have not been deciphered, nor have facsimiles been published.

update>I am happy to be corrected, especially during National Archive Month or whatever. The Archives of American Art has Hampton’s writing available on microfilm. An independent researcher of enciphered documents, Dennis Stallings, has an extensive site about decoding what he calls “Hamptonese.” And in 2004, San Jose State computer scientists Mark Stamp and Ethan Le published a statistical analysis of Hamptonese. Because it doesn’t correspond to a typical substitution code, they defer to the previous hypothesis that Hamptonese is “the written equivalent of ‘speaking in tongues.'” In other words, not their department, either.

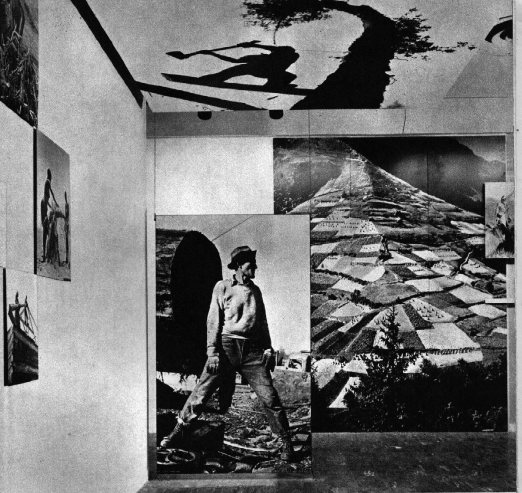

image from Naives [sic] and Visionaries, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1974, via stopping off place

Hampton obviously showed someone his work, because there is a photo of him standing in front of it [above], which Michael from stopping off place posted this summer. Interestingly, those crowns were separated from The Throne in some way, and were only donated to the AAM in 2001. Perhaps there is more work–and more story–still out there somewhere.

After it was conserved, in 1976, The Throne… went on a several cities tour. Curator Lynda Roscoe Hartigan wrote an essay laying out as much of the work’s and its creator’s history as could be known at the time. Hampton, who called himself Saint James in his writing, also mentioned a Baptist minister named A.J. Tyler:

Despite Hampton’s Baptist background, he was not a member of a congregation in Washington. Believing that there is only one God, Hampton considered different religions unnecessary. An important encounter with the Reverend A. J. Taylor, a popular black minister who died in 1936, may have occurred in one of the neighborhood churches he occasionally visited. The Mount Airy Baptist Church, where Taylor served, was not far from Hampton’s boarding house, and it is possible that the Reverend inspired Hampton during a revival meeting or Sunday sermon.

Tyler was noted for having said that in Washington, the city of monuments, there were no monuments to Jesus. During his ministry, he installed an electric sign, “Monument to Jesus,” over the door of the Mount Airy Baptist Church.

Hampton may have been intrigued by the minister’s idea for a monument to Jesus; the word “monument” is entered in one of his notebooks, and numerous references to A. J. Tyler appear in the assemblage. Many pieces bear labels reading “Tyler Baptist Church,” although Tyler never preached in a church of that name. Hampton also indicated in his notebooks that Saint James was the pastor of “The Tyler Baptist Church.” Tyler may thus have been a model and an inspiration for Hampton, whose commemoration of the Reverend seems to have mingled freely with his belief in the Second Coming.

Emphasis added because, hello, “the city of monuments.”

As spectacular as Hampton’s creation is, it’s not at all clear that he himself considered it to be art. In fact, the texts he left behind almost certainly refute that categorization. These are devotional objects, grounded in his complex religious experience. With American Indian tribes, the Smithsonian has gone to great lengths to recognize and preserve the cultural and spiritual aspects of relics and artifacts; I wonder if there has ever been discussion of dealing with Hampton’s work in the same context.

James Hampton, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly, 1950-64 [americanart.si.edu]

The report also mentions the 100 Pasadena type boxes, plus “as many as 16” additional Boxes identified in the CR that were “given as gifts or sold.” Two of those 16 are the

The report also mentions the 100 Pasadena type boxes, plus “as many as 16” additional Boxes identified in the CR that were “given as gifts or sold.” Two of those 16 are the