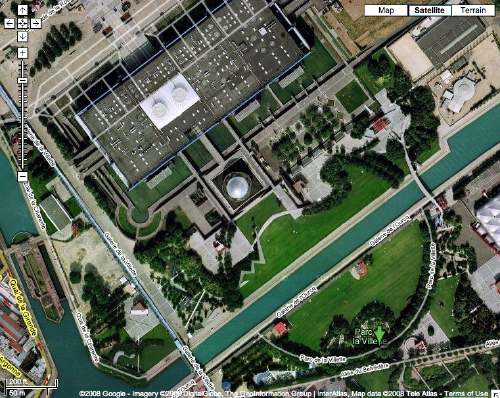

But darned if it isn’t pretty damn close. La Géode is a mirrored geodesic dome housing a hemispheric Omnimax theatre. It’s part of the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, a science museum opened in 1986 in Parc la Villette, which I confess, I only knew as the site of Bernard Tschumi’s red follies. [There are a couple visible in the background here, and judging from this photo from another angle, they’re rightupthere next to the dome.]

At 34m across, Adrien Fainsilber’s stainless steel-clad Geode is the nearest approximation to the physical presence of a Project Echo satelloon that I’ve found. [Thanks to Stuart, actually, who tipped me to the recent post on extremely impressive shiny balls on deputy dog.]

Fainsilber’s site has more pictures, including the grainy-nice snap of the Geode nearing completion. and this amusing explanation:

Symbole de l’Univers, le reflet des nuages suggère la forme des continents et offre une vision immatérielle de l’environnement.

L’écran hémisphérique de 26m de diamètre de la salle de spectacle a engendré la forme sphérique de l’enveloppe.Symbol of the Universe, the reflection of clouds suggests the form of continents, and offers an immaterial vision of the environment.

The hemispheric screen of 26m diameter in the salle de spectacle [heh] engendered the spherical form of the envelope

I love it, a loopy mix of grandiose over-symbolism and bureaucrat-pleasing rationalization. As if the shiny steel awesomeness of the dome was somehow just the unavoidable by-product of the program the humble architect received. [Qu’est ce qu’on a pu faire? C’est logique.] Sure beats the “but it’s art!” pitch that was the last straw for the suits backing the Pepsi Pavilion.

Also, it’s an amusing stick in the eye of the deconstructionist, “form before function” conceit that Tschumi and collaborator [sic] Jacques Derrida put forward for the rest of the park.

I don’t know the story of the creation of Parc de la Villette, but Tschumi sounds like the Robert Irwin to Fainsilber’s self-important Richard Meier. Looking at the landscaping, la Geode has gone from being a Symbol of the Universe to just one stop of Tschumi’s David Rockwellian Cinematic Promenade. Or to the electron on a hydrogen atom. Which, as I zoom in with the all-seeing Google Eye to watch the picnickers in the Parc, i realize is so true. What if the whole universe were just an atom under the fingernail of a giant?

extremely impressiv shiny balls [deputydog.com]

Fainsilber > Realisations > CSI [fainsilber.com]

CSI and la Geode, and guests reading Le Monde, apparently, and letting their kids run wild [google maps]

Metaphysics of Parc de la Villette [gardenvisit.com]

Holy ^%$&! Man Smuggles Art To The &%#$ing Moon!

Holy ^%$&! Man Smuggles Art To The &%#$ing Moon!