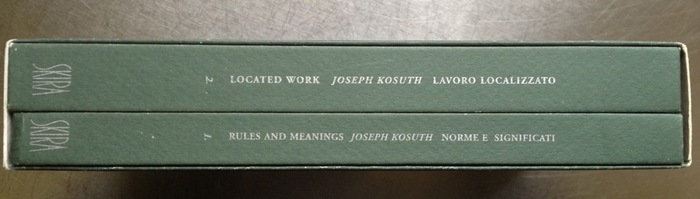

Sometimes it takes a little while to piece things together. I just opened a book for the first time which I bought in 1997: Lavoro Localizzata/Located Work, the 2-volume publication that accompanied Joseph Kosuth’s July 1995 graduate workshop for the Fondazione Antonio Ratti. Kosuth’s project was to have students write out 1-page instructions for an artwork which would be realized by another student. The resulting show was both the instructions and their realizations, and the objectives were primarily related to upsetting ideas of process and authorship. Alas, none of the instructions in the otherwise bilingual catalogue are translated, so who knows how the images relate. What interested me were the conference essays by eminences like Iwona Blazwick, Francesco Bonami and Nicholas Bourriaud, who graciously made the trek to Lake Como. They’re almost nowhere online, only in an archive here on undo.net.

Bourriaud’s quite explicit on the exhibition, not the artwork, as the relevant unit of art production. I am a bit more sanguine about this quote now that its date is fixed to 1995, and not 1997:

While interactivity has, of course, become something of a buzzword, my concept of interactivity goes beyond gadgetry such as the internet. Interactivity begins with a handshake which is, in a way, much more interesting than all the interactive technical devices on offer. As regards my interest in interactivity, I would like to give the following definition of artistic activity: the artist invents relations between people with the aid of signs, forms, actions or gestures. My first point is that I firmly believe it is difficult, nowadays, to represent reality. In a way, I think we are through with the representation of reality. These are times when we should be producing reality.

Bourriaud’s talk feels like a time capsule, just opened to reveal the important ideas and artifacts of the day, preserved untouched by editing or the passage of time:

In my opinion, the most important process to come about since the beginning of Modern Art has been the transformation of the artwork from a monument into an event. An event is something we have to share if we are ever to understand it; nobody understands an event by himself; it calls for discussion, and an attempt to establish an exchange with the participants or other viewers. Another notion worthy of note is conviviality, particularly important over the last few years. Rirkrit Tiravanija, for instance, at ‘Aperto 93’, installed an area where the viewers could partake of instant soup and noodles. Elsewhere, Angela Bulloch has worked extensively on the idea of putting people together, as has Andrea Fraser with his [sic] lectures held in museums. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, too, has insisted on the same issue with his work regarding cafés, including a recent Grenoble outing. If we look slightly further back in time, Gordon Matta-Clark set up a restaurant in 1971, Daniel Spoerri was wont to organize meals in the 60’s, and Robert Filliou and George Brecht had a shop together near Nice in the late 60’s. The point I wish to make, however, is that while conviviality or the production of relationships between people was, for artists in the 60’s and 70’s, an objective, it is now a starting point for artists.

Art as event. The freshness of instant noodles. We now know more how these have panned out. But what is this about a Felix Gonzalez-Torres café? I was drawing a blank, even though I thought I was pretty familiar with Felix’s work–and more relevant here, perhaps, with his non-work. Maybe Bourriaud’s reference was to a project that had been edited out of Felix’s body of work.

So I looked through the documentation and publications of Felix’s work. The only exhibition in Grenoble he’s listed in was “I, Myself and Others: a place to come to” a group show curated by Thierry Ollatt, the director of Le Magasin, which ran from July – Oct. 1992. The show also included Andrea Fisher, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Sean Landers, Philippe Parreno, Philippe Perrin, and Joe Scanlan. The show seems to have been about the title, autobiography.

But the Gonzalez-Torres catalogue raisonné doesn’t list any works as having been shown in Grenoble. There are several go-go boy dance platforms from 1992 listed in the “Registered Non-Works” section, but none have any obvious connection to Grenoble. Seems like a dead end.

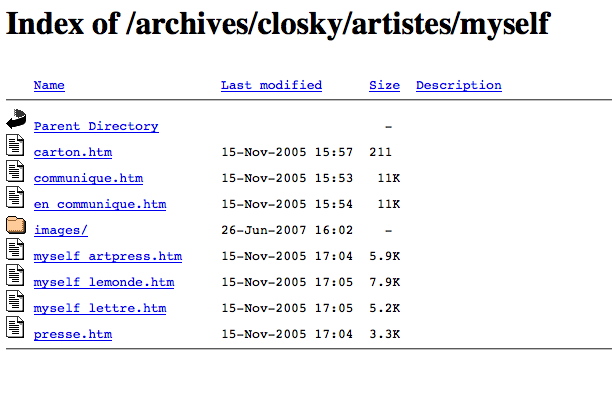

Then as I tried digging up installation shots, or any discussion of the show, I tried looking in the Magasin’s file directory:

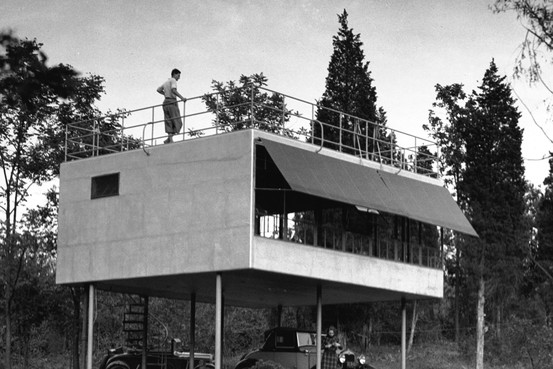

It’s a good day for random corners on servers. Here’s magasin03.jpg, an installation shot with Scanlan’s bookcases.

And here’s magasin02.jpg, the archival image of “Untitled” (USA Today), 1990, Felix’s third corner pour, but the first shown in a museum.

Maybe it’s better to say it’s the first mature corner candy piece. “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner) and “Untitled” (A Corner of Baci) both came before it, but the former is defined by the number of unwrapped [and therefore increasingly gross] cookies, and the latter is small (ideal wt: 42lbs) and pricey to replenish. So “Untitled” (USA Today), ideal wt. 300 lbs, which was shown at the New Museum at the end of 1990, has a symbolic weight and title, and has the take-one-and-replenish dynamic figured out. It also turns out that “Untitled” (USA Today) was originally exhibited with the title “Untitled” (Mirage). The work was shown in at the same time, December 1990, in Berlin, and in 1991 in Kassel, in a two-person show with Cady Noland. [Gotta look that one up next.]

I guess what interests me is not the evidence of shapeshifting and mutability in Felix’s work, which is normal for an artist as he goes along, but which is also a specific characteristic of Felix’s work in its public and posthumous incarnations. It’s how foreign Bourriaud’s brief mention felt to me, how unrecognizable, how far from the way Felix’s work–and particularly the candy pieces–has come to be perceived and discussed. I think the conviviality thing is still valid, so maybe it’s not so far, but I just can’t imagine ever describing his work in terms of a café. Rather than frag Bourriaud, though, it makes me think how prone we are to settling into our experiences with art, and how the present inevitably overwrites not the past, but our memory of it. I know people who know what was in this show, but it never occurred to me to ask, because I never realized I didn’t know.