I’m getting used to not knowing every work David Hammons makes privately, which he may or may not announce until years later. But I am not dealing well with only finding out about public sculptures commissioned more than three decades ago, which turn out to still be chillin’ in the random corner of a park in Atlanta.

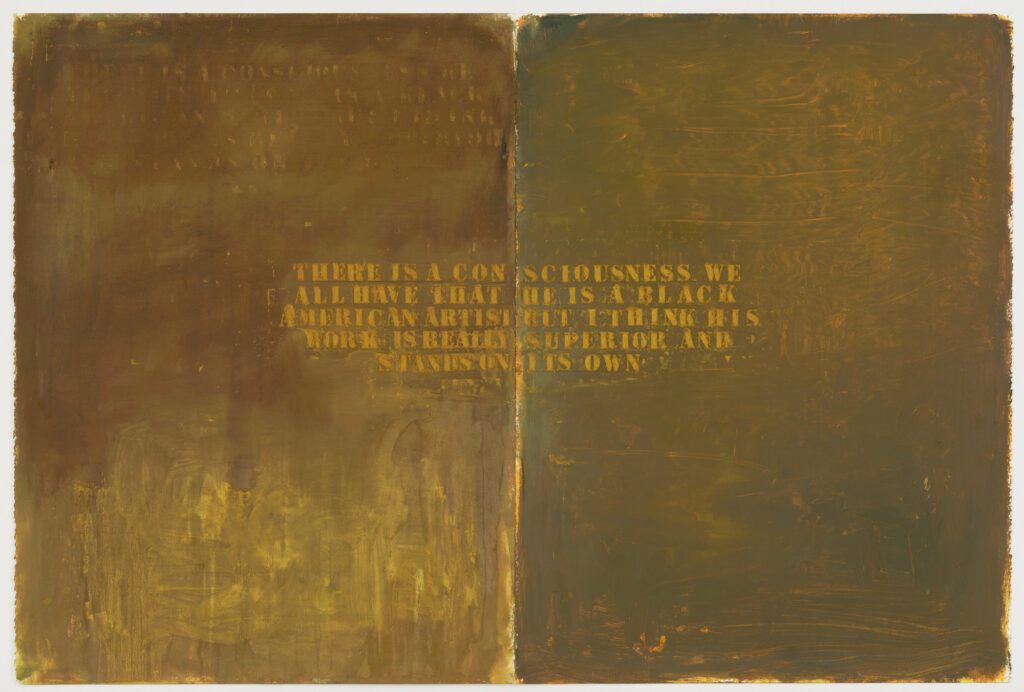

TBF, Free Nelson Mandela IS mentioned in the 1988 intro to Dr. Kellie Jones’ 1986 interview with Hammons, one of the rare, foundational texts on the artist and his practice. But it never occurred to me that it wasn’t just a historic occurrence.

Anyway, it is a giant boulder with a “fan-shaped display” of iron bars topped with barbed wire. When it was originally installed, the gate in the prison-like fence was padlocked shut, and the artist had purportedly buried the key under the sculpture. Probably when it was moved to its permanent location in Piedmont Park, Hammons entrusted the key to Atlanta’s politicians, who opened the gate after Mandela’s release from prison.

The sculpture’s wikipedia page doesn’t seem to have been updated since 2012, but by Mandela’s death in 2013, it had been cleared of extraneous, artist-unapproved shrubbery. The interpretation of the Smithsonian’s public sculpture inventory description has the inscription on the work’s back. Would that also have been behind or “inside” the prison fence? I don’t know. The current siting definitely makes the inscription feel like the front, though.

What seems more interesting is how formally resonant this sculpture is to Hammons’ other works of the time. Like, specifically, Rock Fan, the giant boulder topped with antique fans Hammons installed at Williams College in 1993, which is only the biggest of his rock- and fan-related works, if not the only politically topical one.

The full/official/original title of the work is Nelson Mandela Must Be Free to Lead His People and South Africa to Peace and Prosperity. Which, with meddlesome South Africans in the news lately, makes me wonder if Hammons would make a JAIL ELON MUSK sculpture, perhaps in a park in Pennyslvania.