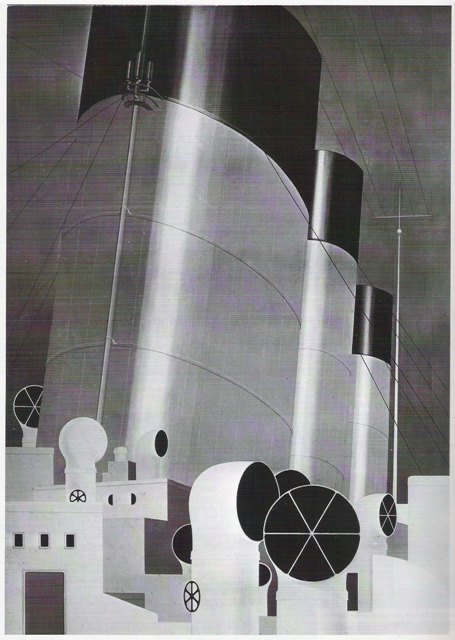

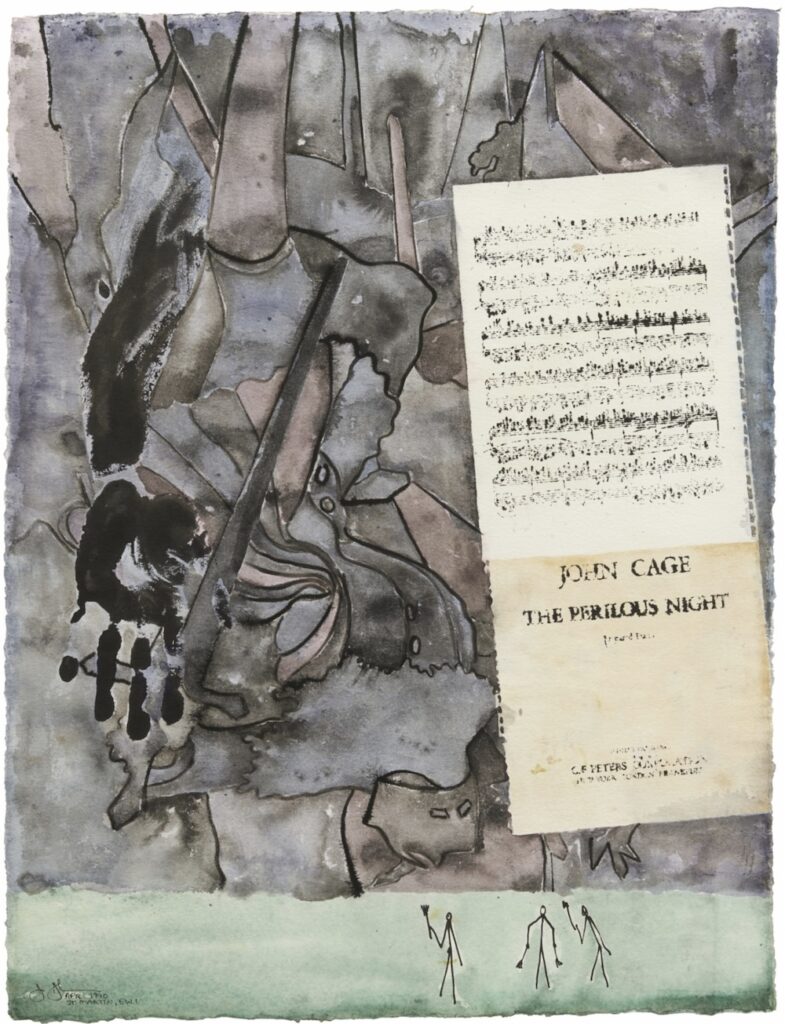

I was excited to read Nicole Acheampong’s feature on David Hammons in art issue of The New York Times’ T Magazine because I knew it would focus on some of the artist’s less documented works off the beaten art world path. [They’d asked me about images of Hammons’ public artworks in Savannah, but opted to not go the appropriated Google Streetview route.] And it does, and it’s great, and it’s especially nice for pointing me back to a profile I misesd in 2018 by M.H. Miller of LES publisher, poet and longtime Hammons whisperer Steve Cannon.

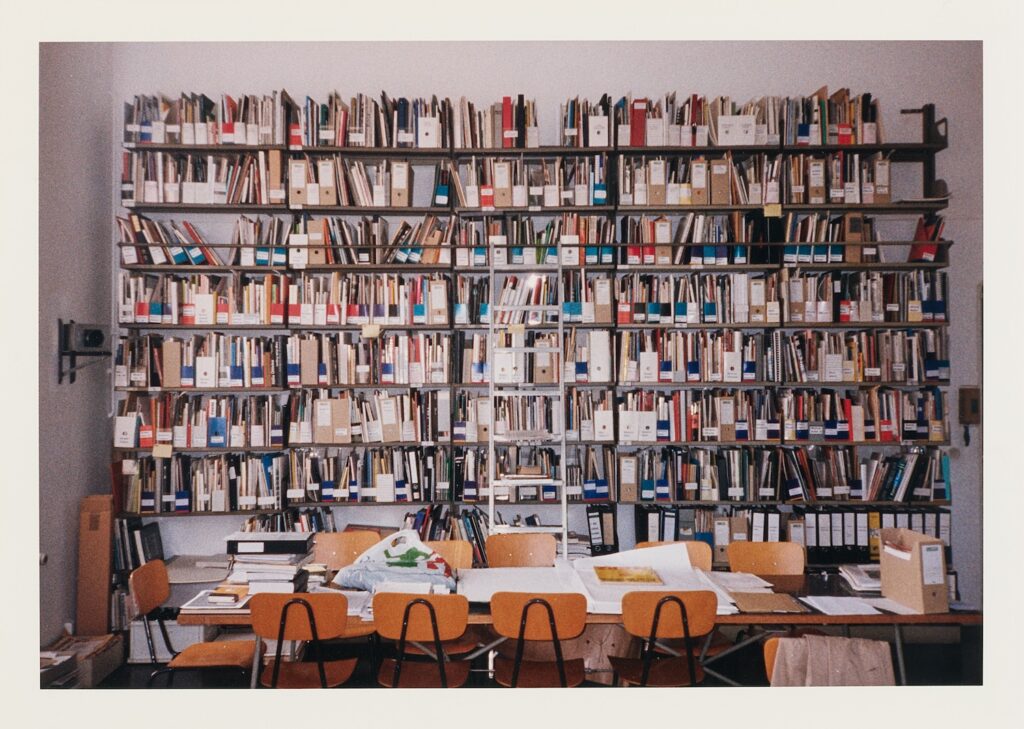

Cannon is one of the creative suns like East Village photographer Alex Harsley who looped Hammons into their regularly orbit from the early 1990s. In the white artworld, Hammons developed a reputation of being aloof, reclusive, evasive But the truth is, he just had his own people he’d rather be in dialogue with, and Cannon has definitely been one of them.

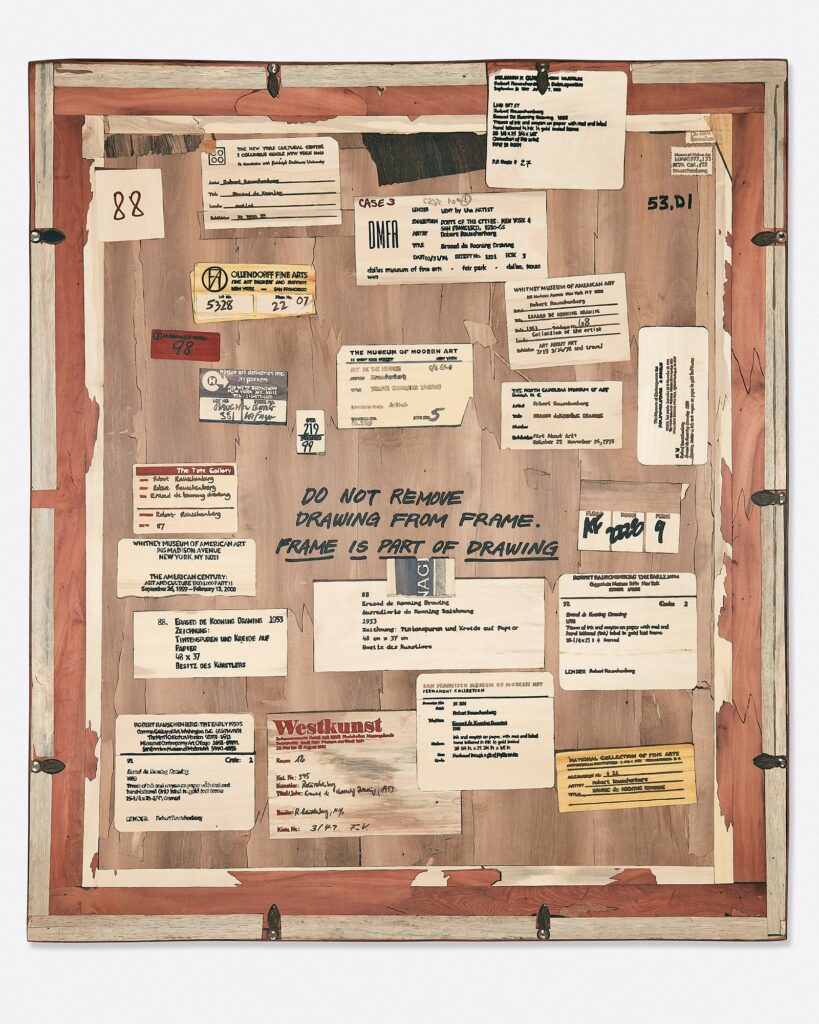

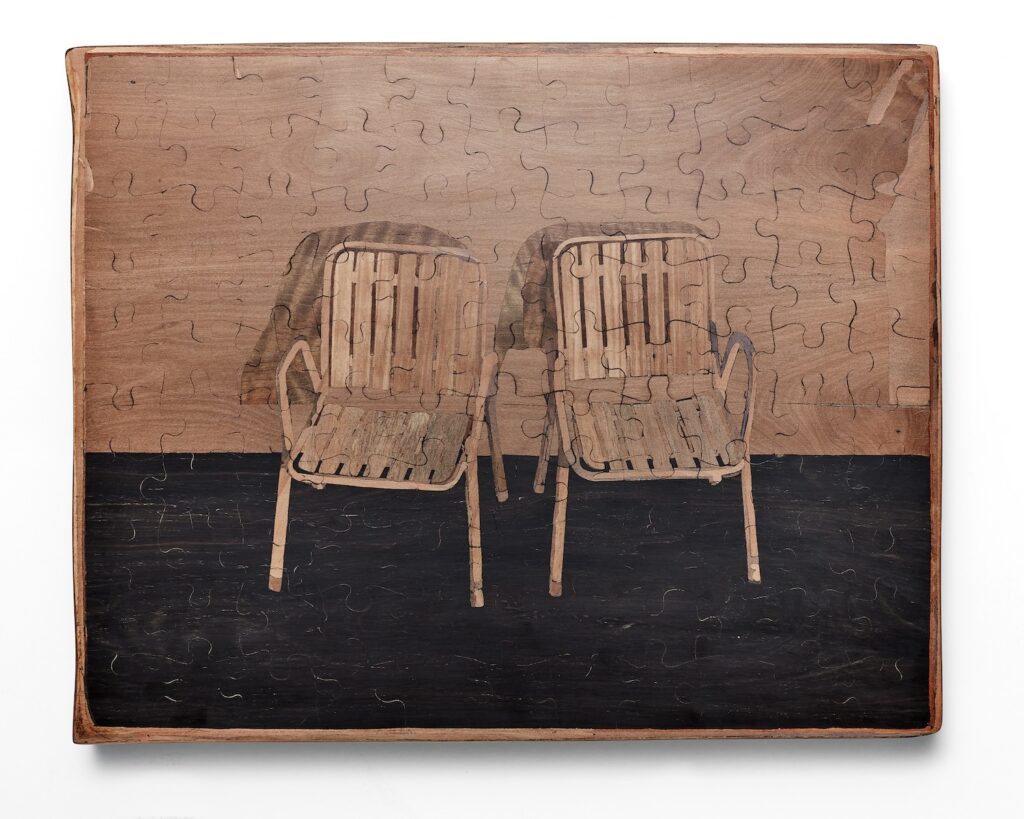

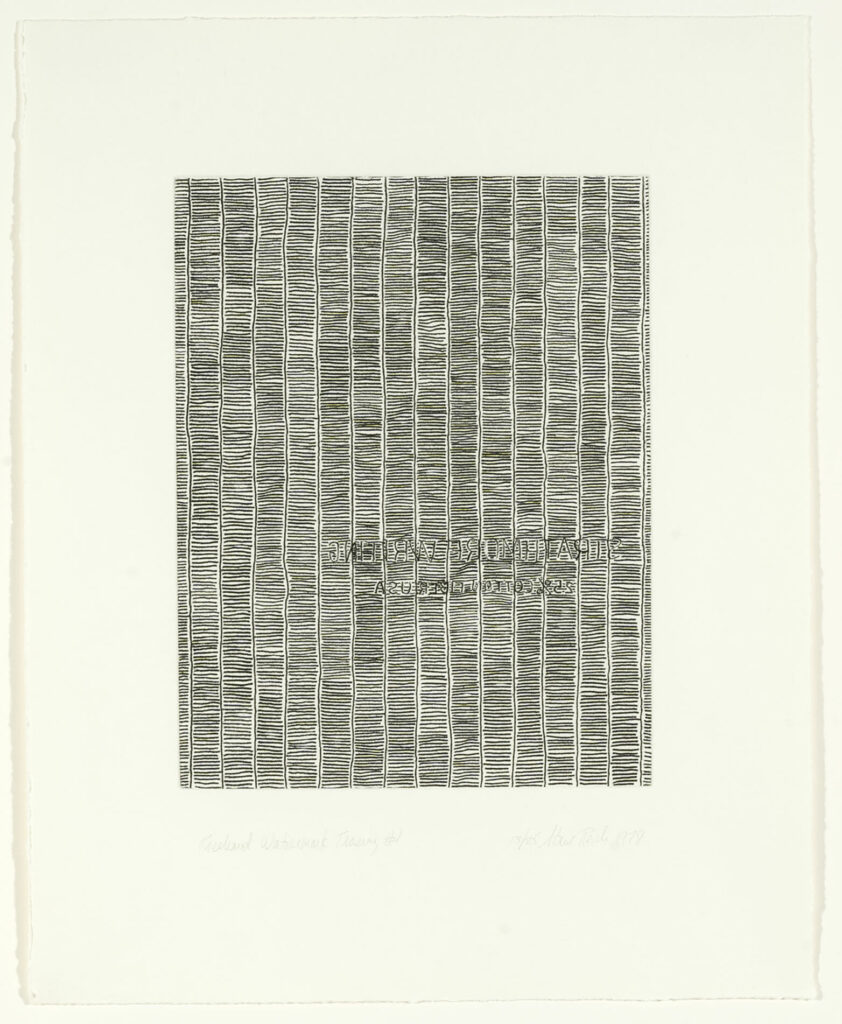

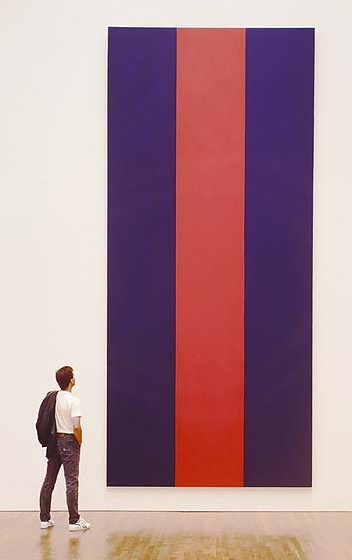

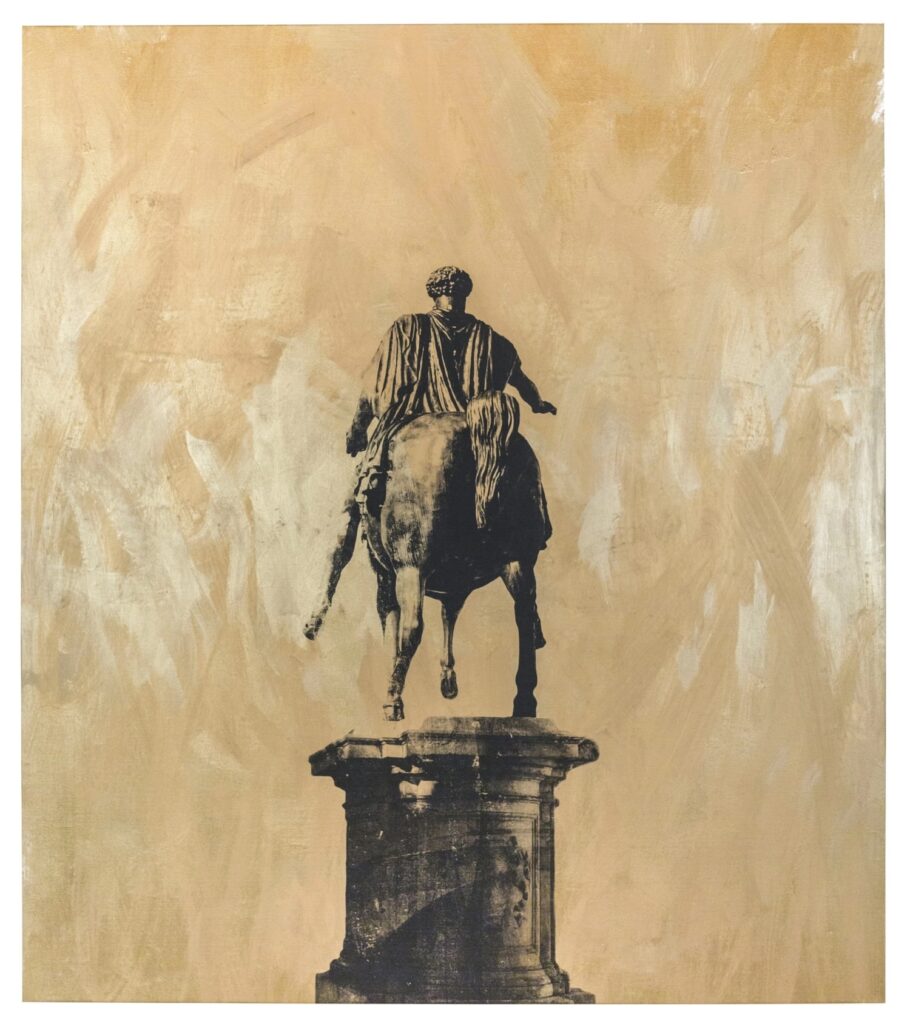

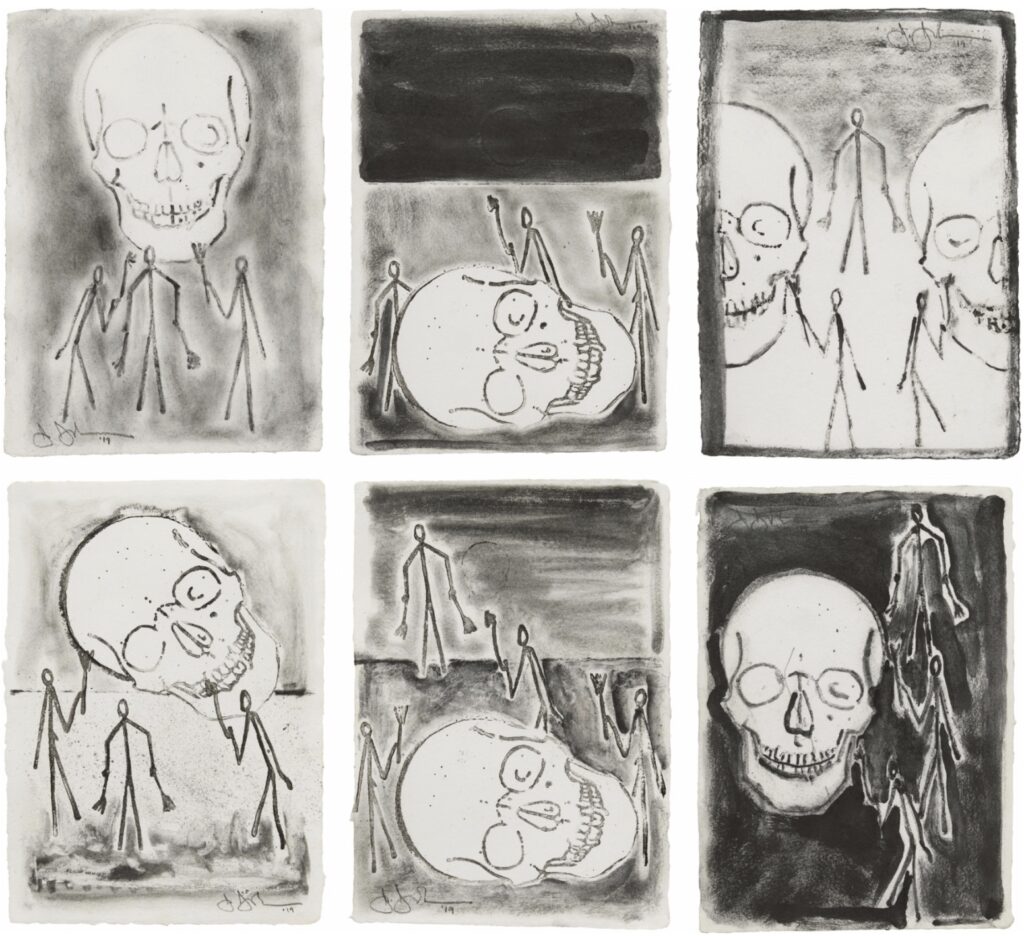

But I was stunned to read Julia Halperin’s cover story about Cady Noland, which tracks the artist’s rise, her apparent withdrawal from the art world—and the rumors or sniping around it—and her recent return to exhibiting her work. Noland’s dedication to the precise positioning and presentation of her work is an ongoing theme, along with the power her work derives from attention some saw as excessive.

I was stunned even though I’m quoted in the article—as “a Noland obsessive,” which lmao is going straight on my bio—stunned because though she refused an interview, Noland agreed to respond to Halperin’s inquiries. The article is thus replete with parenthetical denials of rumors and clarifications of others’ statements, as if she’s carefully correcting the position of each element in her narrative.

Noland also provided the Times with previously unpublished Polaroids. And they confirmed that the artist has been involved in the new installation of her work opening at Glenstone in less than two weeks. Also that the Raleses did indeed buy out her entire show at Gagosian. What is a collector but an obsessive with ten billion dollars?

The Secret Art of David Hammons [t mag]

A Blind Publisher, Poet—and link to the Lower East Side’s cultural history

Cady Noland and the Art of Control