“Beginning October 17, and spanning three rooms of the Pavilions, Glenstone will share a presentation of works by Cady Noland. Developed in collaboration with the artist, this presentation will mark the first major survey by a U.S. museum of her decades-long career.”

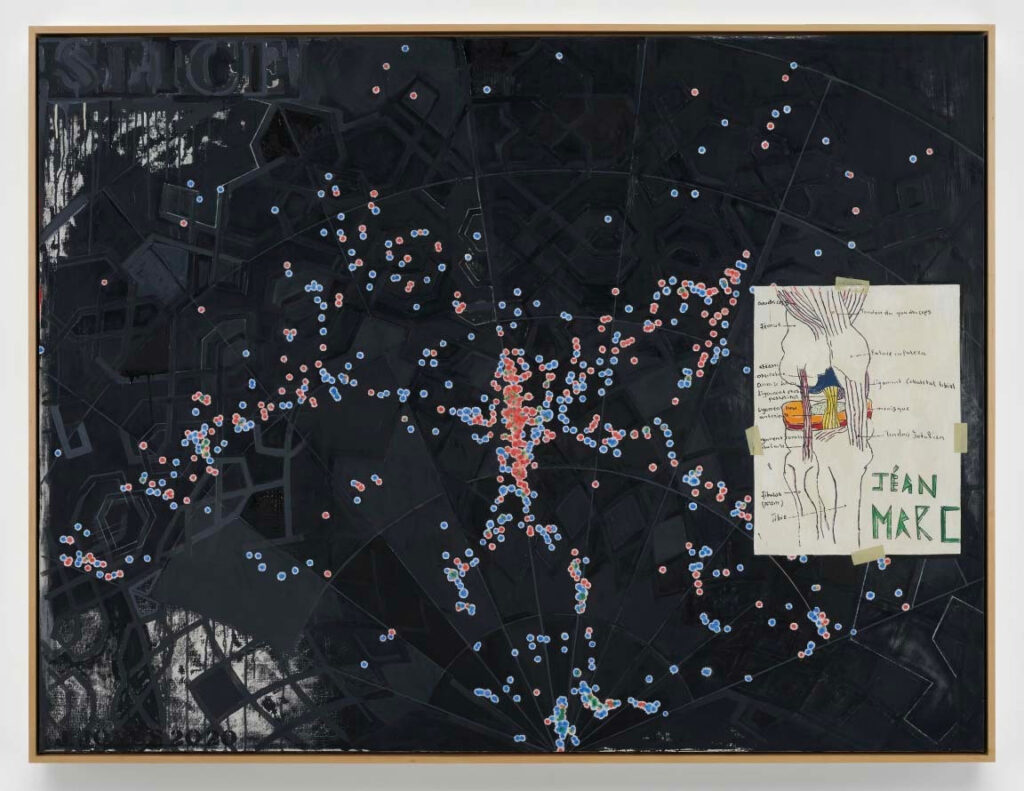

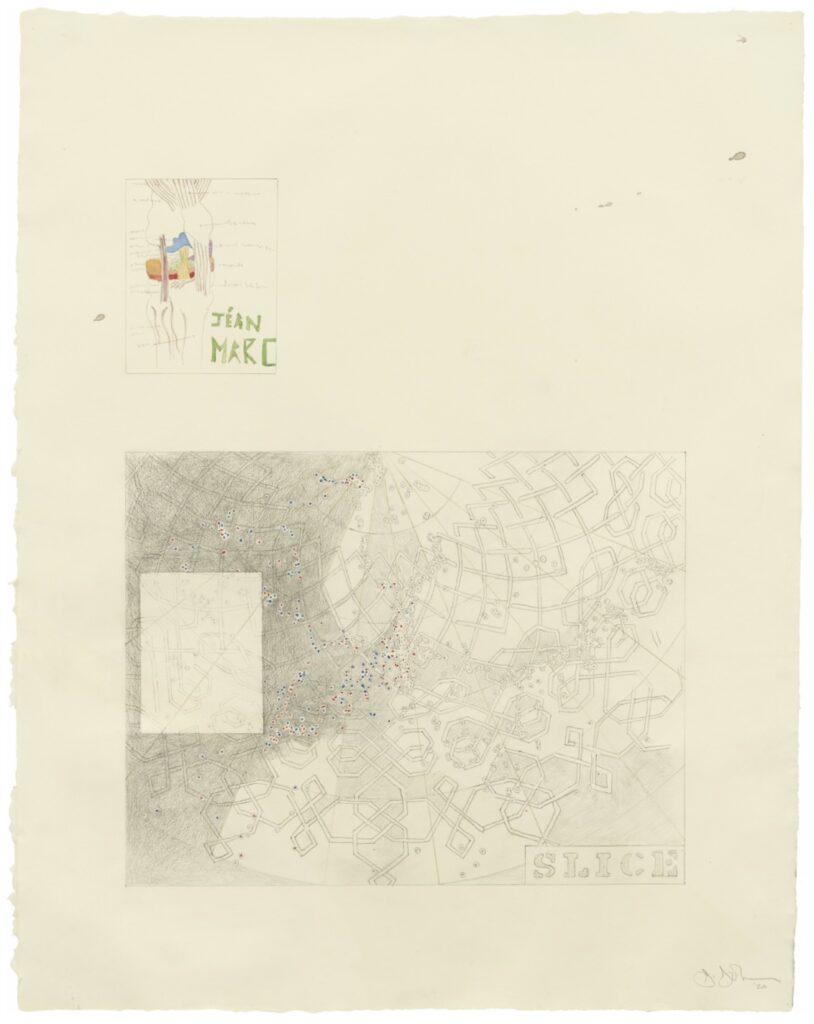

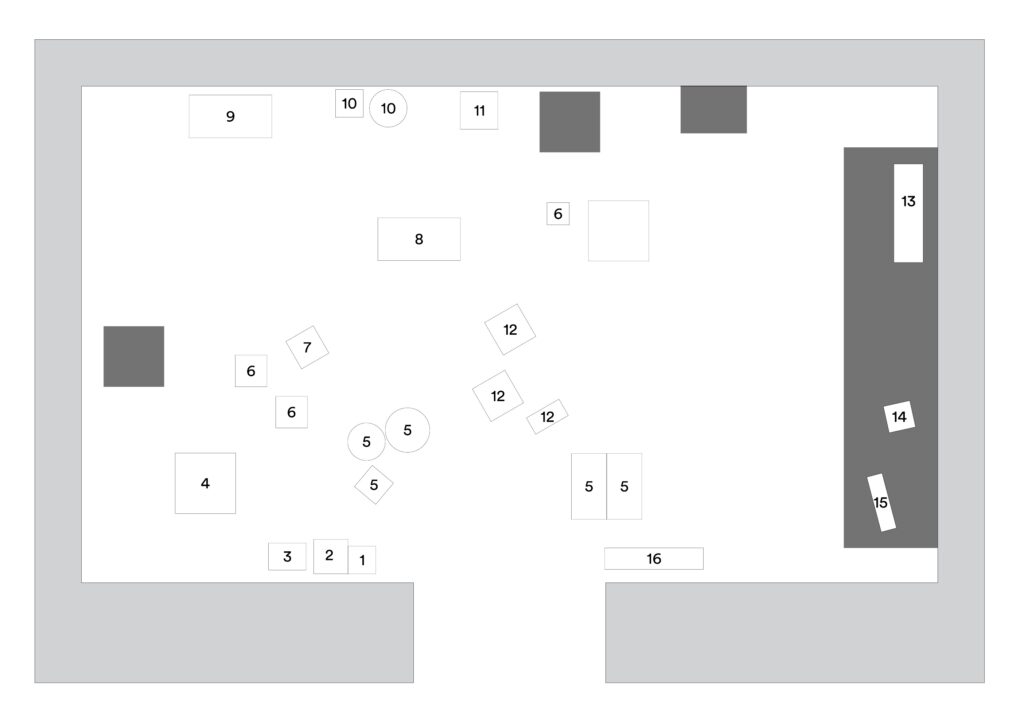

Reader, the presentation has been marked. Last year I poured one out for anyone who’d hoped to buy a new Cady Noland work. But now I feel for anyone who’s been trying to buy a major Cady Noland the last 17 years. Because Glenstone got them all. Look at that map; Glenstone has Cady Nolands even Glenstone doesn’t know about.

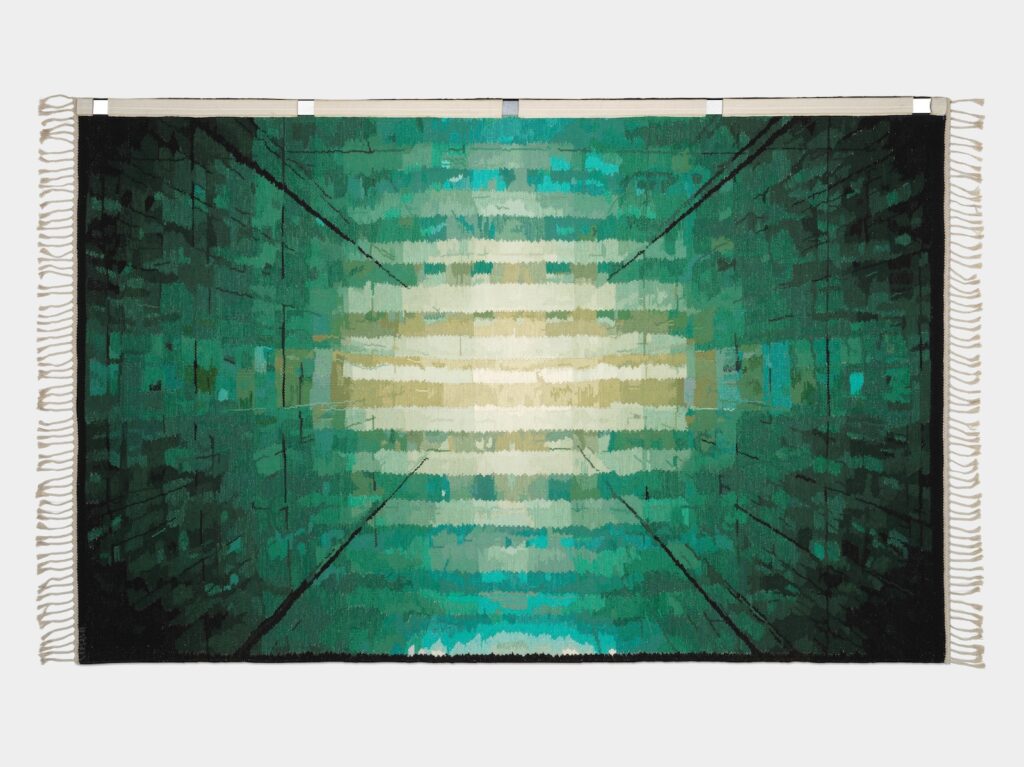

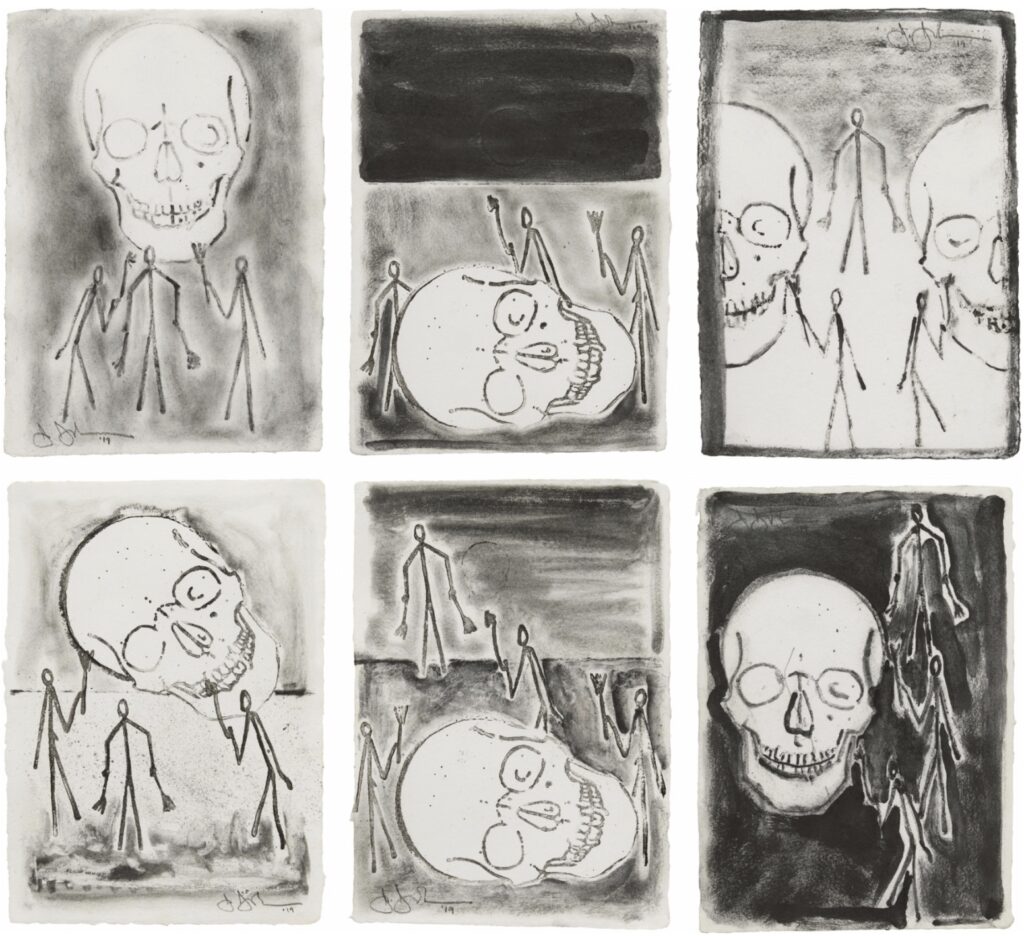

Three of the six open pavilion spaces are Noland’s work. [The others are two galleries of works by Lorraine O’Grady and Melvin Edwards, and the little library.] The first thing you see as you go down the stairs is not a Noland sculpture, but a Noland architectural intervention. At first it read like an Ellsworth Kelly, if only because architecture-scale Kellys were just on view here. Up close, no, closer, inside it, it read like an Anne Truitt, of the back of the Anne Truitts that had backs.

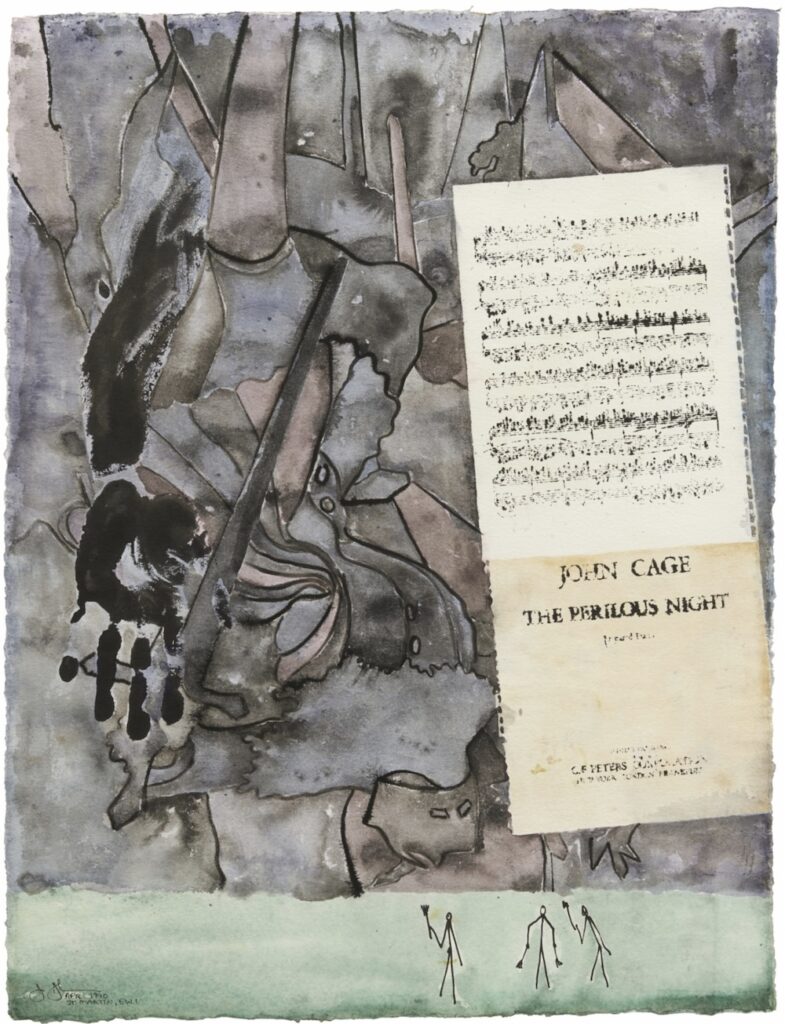

The no photography proscription is excruciating, and I find myself trying to no spoilers my way through this post, as if it’s feasible to say, let’s discuss it after you’ve seen it. The artist adjusted the space to minimize distraction and focus attention on her work, and it works. They borrowed Clip-on Man. Charles Gatewood’s book with the source image is in the library.

The Raleses purportedly acquired Noland’s entire show last year at Gagosian, but it also somehow fills a space three times the size. There is a lot less tape, except when there isn’t.

There are pallet plinths that are not elements of the work, except when they are. There are foam and carpet blocks that precede an installation, except they’re still here. It’s at once pristine and provisional.

The paper labels remain on the white wall tires. You may not ride the tire swings. The internal gear to lift the massive stockade is freshly lubed, but the crank is padlocked. The chain that connected the bench is gone. Oozewald has its corrected and copyrighted stand. The wear on the corners of one (non-mirror-finish) aluminum panel propped on the floor is enough to make the owner of Cowboys Milking weep.

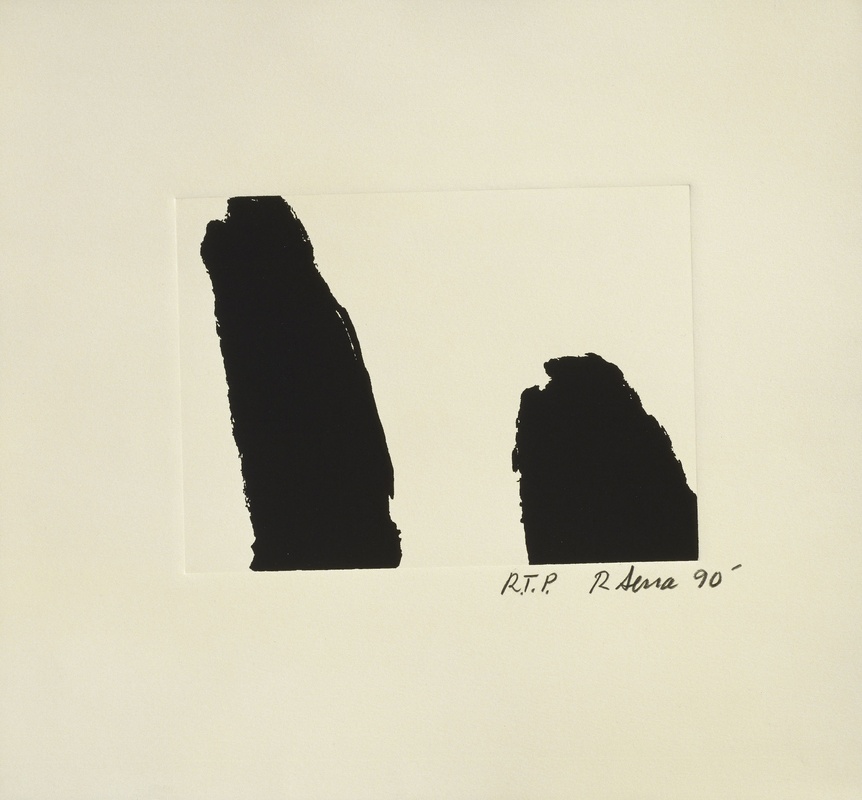

It’s like this survey surveys not only the range of Noland’s work as she made it, but as it was presented, processed and purchased since. Maybe being cast in acrylic and thoughtfully placed in the contemplative suburban art temple of benevolent billionaires is not, after all, all bad.