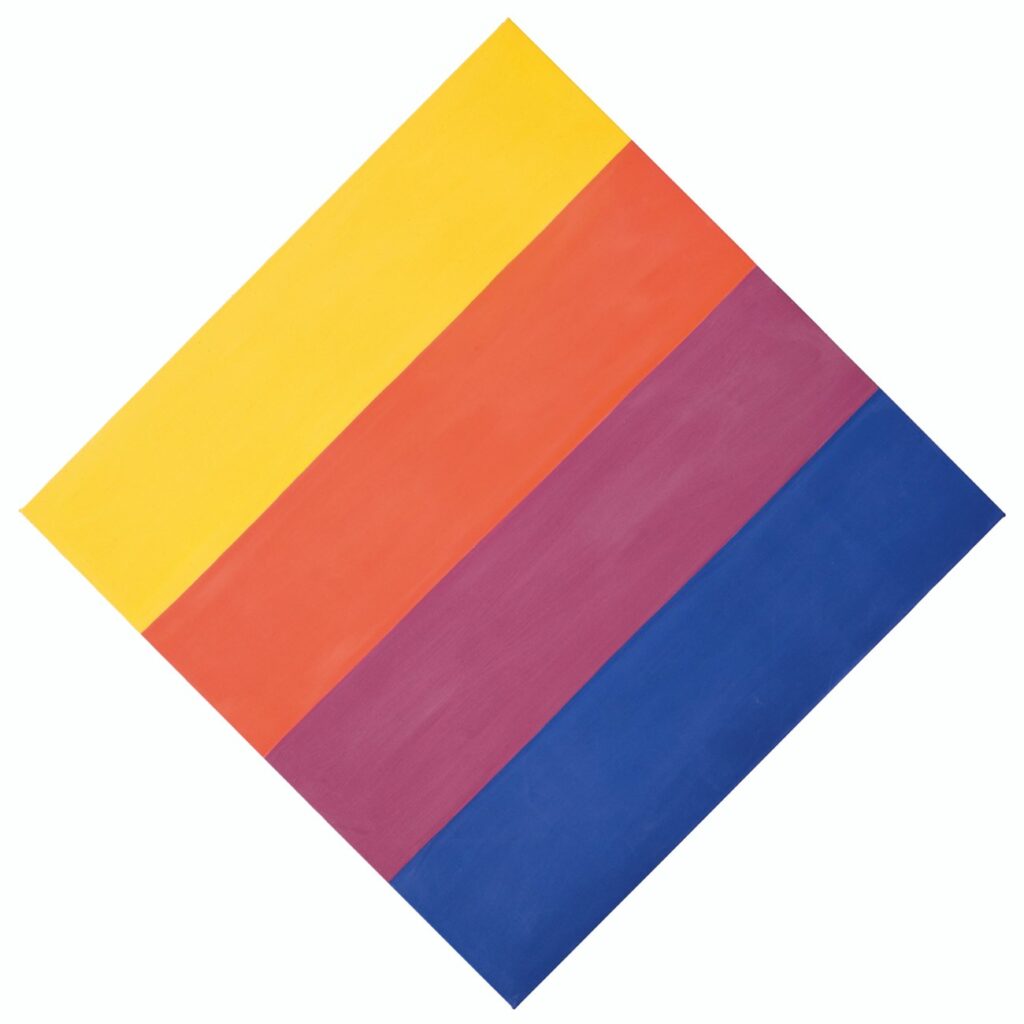

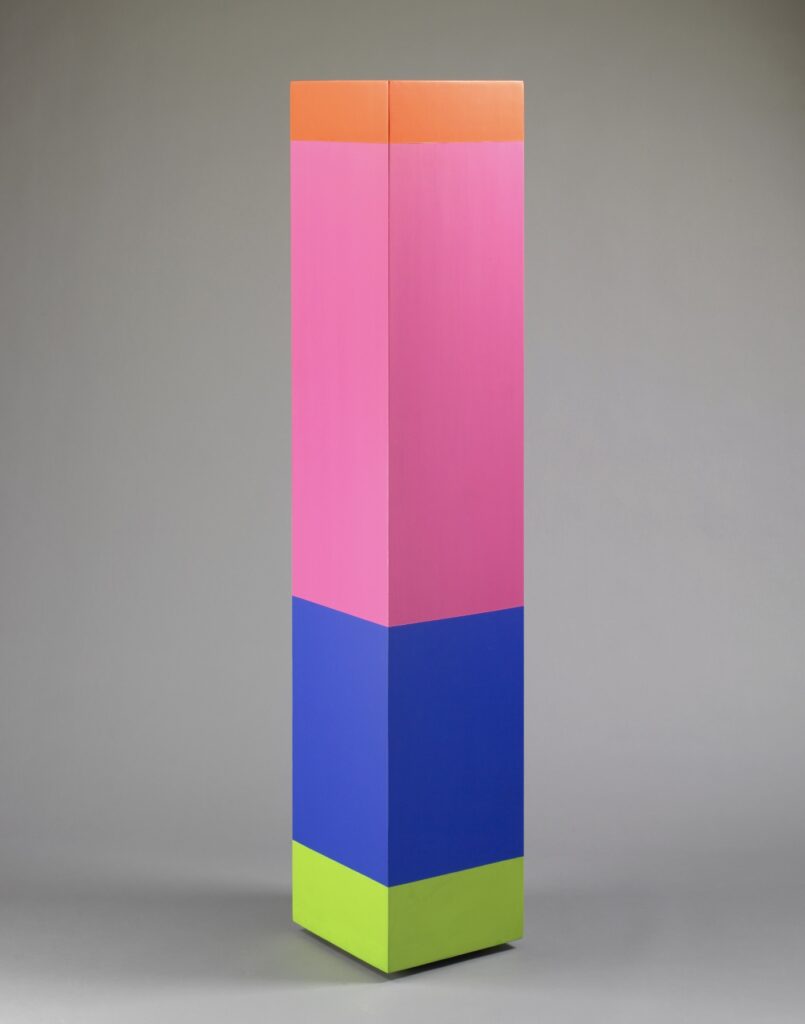

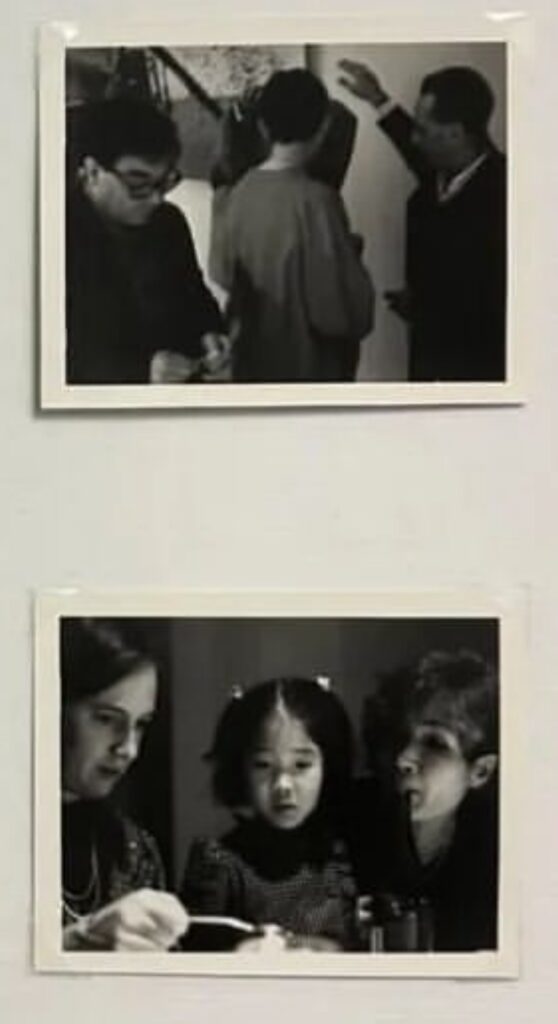

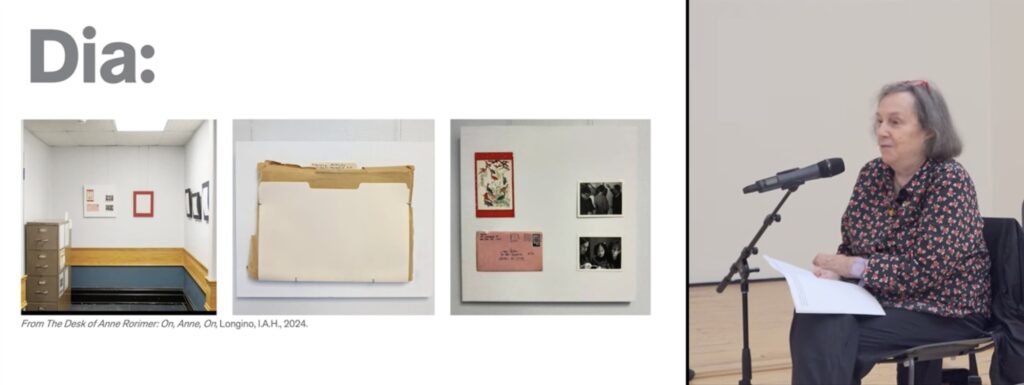

Here are snapshots of On Kawara’s family attending Gerhard Richter’s New Year’s party.

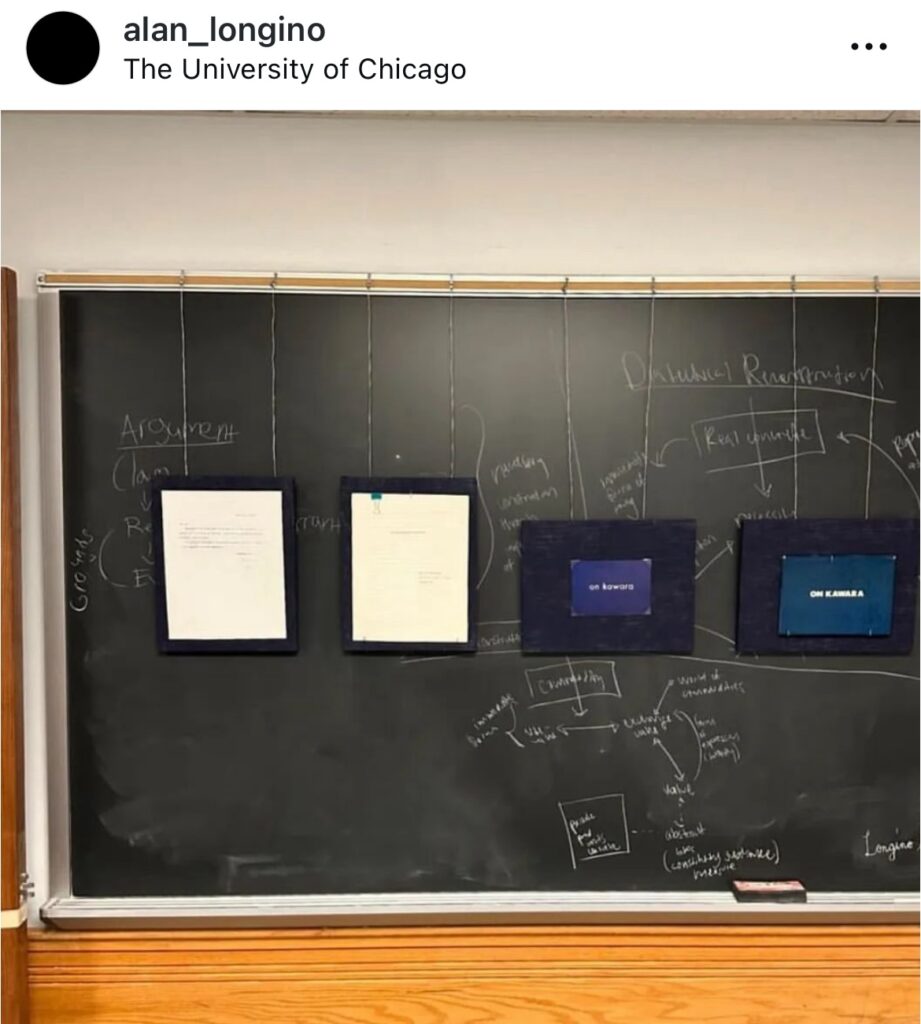

They were included in, “From the Desk of Anne Rorimer: On, Anne, On,” an exhibition staged over a series of weekends in Apr-May 2024 in what looks like a student lounge at the University of Chicago. The material was taken down every night so it wouldn’t disappear. It was the fourth and final show of Longino, IAH, a curatorial project by post-war Japanese Art History graduate student Alan Longino. Longino’s idea was a show focused on an art historian, and Rorimer gamely opened her lifetime of files and correspondence, and archive of artist interactions to him.

More than most artists, Kawara’s work was so intertwined with the medium of interaction, correspondence, and daily activity, and the professional and personal ephemera give glimpses of life beyond the edges of his practice.

The identification of the snapshots was from Rorimer herself, who mentioned the exhibition and Longino in late June at Dia, where she and curator Jordan Carter discussed her work with Kawara and other Dia artists.

Rorimer began working with Kawara in 1979, when she included him in the 79th American Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. Judging by the age of Kawara’s daughter in the lower snapshot, the party would probably have been in the late 1980s. A more intrepid soul than I might deduce the year from the date formats of paintings produced around the holidays. Or it’s on that pink envelope. [update: which, that Sojourner Truth stamp was issued in 1986.] Or just ask Rorimer.

Of Longino, IAH, there is a text by Calvin Lee on Longino’s Google Drive, but the most thorough documentation of the show for the moment is Longino’s Instagram. I was stunned and saddened to learn Longino, 36 and at the very beginning of his career, passed away from cancer in July, barely a week after Rorimer & Carter’s conversation.

Longino, I.A.H. [longino-iah.com]

previously, related: I Hunted Butterflies