Five years ago today, Cady Noland learned that her 1990 sculpture Log Cabin had been destroyed and refabricated in Germany without her authorization, and that the new version (or whatever it was) had been sold to a “mystery client,” Cleveland collector Scott Mueller.

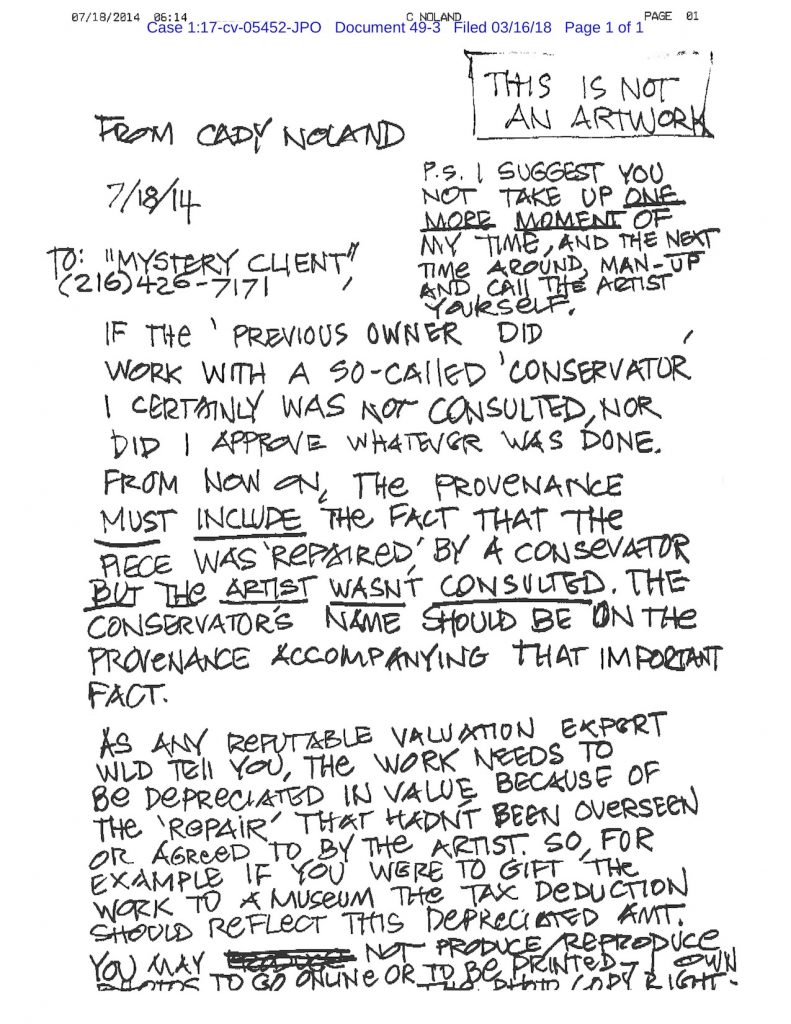

Mueller had a buyback clause in his purchase agreement, allowing him to unwind the transaction and receive his $1.4 million back if the artist contested or rejected the authenticity of the work. Which is exactly what happened. Mueller had to sue Galerie Michael Janssen to get his money back (which he presumably did; the case was ultimately withdrawn.) But in 2017 Noland, who had not been a party to Mueller’s dispute, but rather its subject, filed a copyright infringement claim against Janssen and collector Wilhelm Schürmann, for the unauthorized replication and distribution of her artwork.

Artistically, one would think it hinges on the artist’s determination of the conceptual nature of the sculpture Log Cabin Facade. Because they had a blueprint, Schürmann et al apparently figured they could refabricate the work as needed, no problem. That turns out to not be how Noland conceives of the work, however; her court case emphasizes the importance of the original logs she ordered from Montana, the stain she later instructed Schürmann to apply, and the 25 years’ patina the sculpture acquired. All of this was destroyed and replaced without her knowledge.

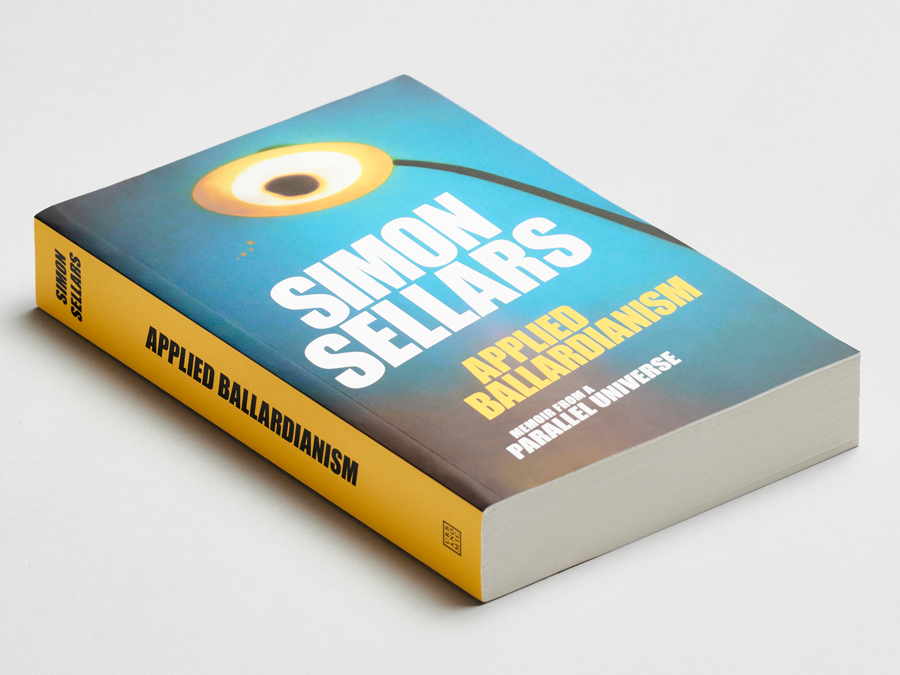

The document read here is one of the most recent filings in the case. It is a memorandum from the artist (via her lawyer) arguing against the defendants’ motion to dismiss her complaint, which has been amended and re-argued three times in three years.

Her claim is fairly atypical, and complicated, and Noland’s interpretation of copying, and fair use is, if successful, probably a net negative for the culture. The Office of Copyright’s denial of copyright registration to Log Cabin, however, feels like an egregious error.

This recording was made on the beach at Emerald Isle, North Carolina. The waves end up sounding like traffic to me, unfortunately, and into what seemed like a pitch black, silent night, some neighbors brought dogs and fireworks.

Download ASMRt-Cady-Noland-gregorg.mp3 [greg.org, mp3, 33mb, 1:09:37]