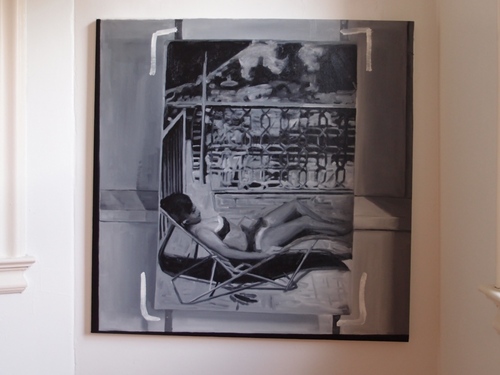

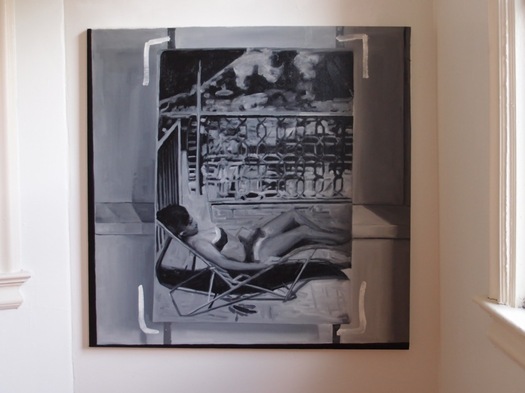

Destroyed Richter Painting #03

First off, a huge thanks to everyone who came to the opening of Richteriana Saturday, and a high five to Magda, Postmasters and the artists in the show. It really does look great, and interesting, and provocative. If you can, you should definitely see it in person.

Destroyed Richter Painting #04

Which is actually one reason I debated not posting images of the Destroyed Richter Paintings paintings I put into the show. One of the real drivers of making the paintings was to approximate the experience of standing in front of paintings that could now only be seen through photos. Or transparencies. Or JPGs. And to measure what the difference is between these different modes of mediated perception.

Destroyed Richter Painting #02

I did not have access to the actual dimensions of Richter’s original works, but I worked hard to deduce the size as well as to approximate the image, so as to make the feeling of seeing a picture in person as authentic [sic] as possible, even while acknowledging that Richter made such an experience impossible.

Destroyed Richter Painting #05

But looking at jpgs of paintings [of jpgs of paintings of photos] obviously falls short of this idealized encounter. As so much of our art encounter/consumption does. It’s a distinction that most people miss or gloss over, but which is not lost on Tyler Green, who recently addressed the subject of critics reviewing shows they haven’t seen by tweeting, “I never ‘work’ off JPEG.”

Richter actually showed most or all of the paintings depicted here between 1964-67, so in a way, there’s an aspect of going back in time, to encounter Richter and his work at the beginning of his Western career. A time when the context of the work wasn’t hype and adulation and skyrocketing prices, but bafflement, resistance, and indignation. There are early photo paintings that survive only because someone bought them or kept them; so these works, which were once good enough to be exhibited or put on sale, were rejected by the market before they were ultimately rejected by the artist himself.

Destroyed Richter Painting #01

The one exception/mystery is Grau. This is one of the 70+ paintings that did make it into the catalogue raisonne, but which are now listed as destroyed. And if there’s a surviving image of the three destroyed grey monochromes [CR395-1-3], I couldn’t find it. So all that’s known publicly is the dimensions, and the unusual support [wood panel]. But that’s part of the beauty of the grey paintings, I thought, that you could think you could credibly extrapolate an actual painting from such minimal information. And seeing it in person really makes me miss Richter’s version–and to wonder what happened to it.

Tag: destroyed

Editing A Life In Painting

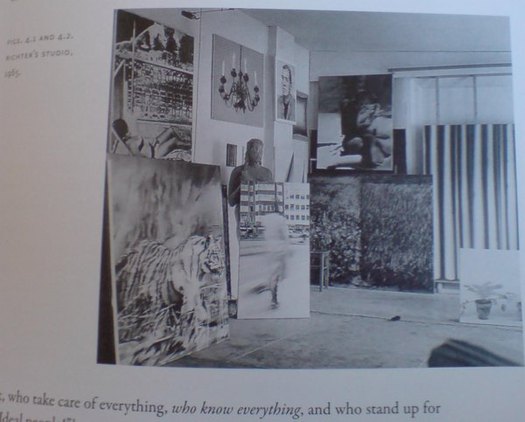

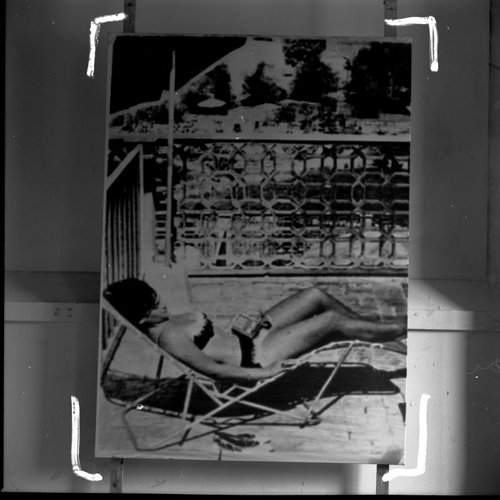

Richter’s studio, 1965, as seen in Elger’s A Life In Painting. Note the lady in the bikini on the left, which

Jasper Johns is well known for destroying his early work, thereby managing and reordering the story of his art by altering its history. But he is by no means alone. Gerhard Richter does it, too. And by turning his image archive and even the list of his paintings into works of art in their own right, Richter might have Johns beat.

Here is an excerpt from Dietmar Elger’s 2009 Richter bio/history, A Life In Painting, which I hadn’t noticed until recently:

In fact, Richter destroyed most of his early [i.e., pre-1962, as well as early photo paintings] works. They are known now only through reproductions in his well-organized archive. There was never, however, a radical break of the sort suggested by his self-organized catalogue raisonne (Werkverzeichnis, or “work list,” as he terms it). This catalog is one of Richter’s ongoing projects–a work in itself–and has long been a subject of controversy. Catalogues raisonnes are ordinarily assembled by scholars, who strive to document every authentic work by a given artist, and are organized chronologically. For Richter, the point is less to establish authenticity than to establish a trajectory within the artwork that he deems acceptable. His catalog does not include all of his work, nor is it consistently chronological. The artist has always excluded his earliest work; while some critics would like to believe that it documents the first paintings that incorporate media images as source material, this is simply not the case. [pp. 44-5.]

Tisch/ Table, CR-1, 1962, via gerhard-richter.com

Count me as one of those critics, or viewers. I knew he’d painted works before then, but I had no idea, for example, that Tisch, which is listed in Richter’s definitive-seeming numbering scheme as CR-1, was actually painted after several other paintings in his catalogue raisonne. It’s No. 1 because looking back from the late 1960s, Richter had figured it was a good place to start.

Richteriana, Postmasters Gallery, 12 May 2012

Destroyed Richter Painting No. 04, 2012, oil on canvas, 110x110cm

Postmasters is pleased to announce:

RICHTERIANA

GREG ALLEN, DAVID DIAO, RORY DONALDSON,

HASAN ELAHI, FABIAN MARCACCIO, RAFAËL ROZENDAAL

May 12 – June 16, 2012

opening reception, saturday, may 12, 6-8

Postmasters‘ new exhibition Richteriana attempts to examine the current canonization of Gerhard Richter, presenting six artists whose works pre-date, update, expand, and subvert “the greatest living artist’s” own.

…[snip much amazing thinking and description of great artists and their work]…

Greg Allen’s Destroyed Richter Paintings channel the elder artist’s own private documentary images back into the photo- based painting feedback loop he once deemed “photography by other means.” They reproduce the experience of encountering Richter’s lost originals, while becoming new objects themselves. By engaging the sprawling Chinese photo-painting industry that has grown up in Richter’s wake, Allen forefronts the market’s incredulous perception of the artist’s autonomy–and his right to declare or destroy his own work.

More to come, obviously.

Previously, related:

a destroyed Richter/Palermo collaboration

“I am practising photography by other means.”

On repainting Gerhard Richter

Overpainted vs Destroyed Gerhard Richter

Infiltration & Replication, Untitled (for Parkett) – Part 2

Untitled (for Parkett), 1994 image via phillips de pury

I’ve been wondering how Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ billboard edition, Untitled (for Parkett) was playing out in the real world. How many of the 84+15+? copies still existed? How many had been installed? Installed and destroyed? Have any been installed and preserved after its permanent site traded hands? Or are most/all of them like mine, still sitting in the box, rolled up, and “incomplete,” waiting? Waiting for what? The perfect wall in the house you’ll never leave? The market to rise too high to ignore?

Untitled (for Parkett), 1994 image via christie’s

What I already knew: seven examples of Untitled (for Parkett) have come up for auction, the first in 2000, and at least three of them didn’t sell, including one example that was missing its certificate. The sales prices, $4,000, $10,000, £6,600, are pretty low in the Felixian scheme of things. More importantly, though, they’re low in relation to real estate, even to high-end wallcovering; if someone were to install the billboard, and then sold the space where it resided, the market value alone–or in combination with the reassurance that eh, whatever, there are a hundred more–is not enough to aid its preservation.

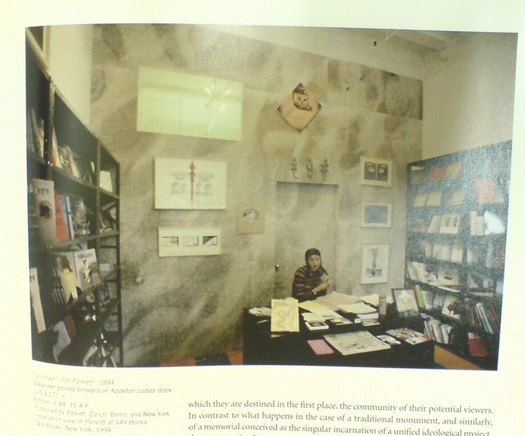

Installation shot, 149 Books, 1994, image via julie ault’s felix gonzalez-torres

Untitled (for Parkett), then is almost doomed by its own nature to exist in a state of fungible incompleteness, or worthless realization, or inevitable destruction. Any billboards that do get installed permanently somewhere will only exist until the paper fades, or the loft is sold, or the kitchen gets remodeled. And then it’ll be gone.

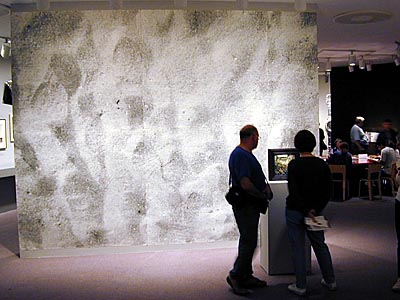

installation view, London, 2001, all images from here on via parkett

I contacted both the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation and Parkett. Allison Hemler, the Foundation’s Director of Archives and Communications did some investigating, and found very little information indeed. There are almost no records of the status of the 84+15 editions, with the exception of #19, which was permanently installedat the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide. [Interestingly, it’s not listed in the collection database, though another Felix piece is. It’s apparently been included in three exhibitions between 1998 and 2009. I’ve emailed the Gallery for any information or images, but haven’t heard back. UPDATE: And a spokesperson told me the work was not in the 2009 show, and is not installed, but is “in the Gallery’s works on paper archive.” So. So I guess there are no known permanent installations of the work right now, despite those being, of course, the only kind.]

installation view, MoMA, 2001

The “several exhibition copies” mentioned in the catalogue raisonne turns out to be just four. Triumph Productions, the Manhattan outdoor advertising printer which created the original 8-panel silk screen is still going strong, but neither the Foundation nor the Estate before it has ever reprinted Untitled (for Parkett) for exhibition, and there are currently no practices in place for doing so.

installation view, dublin, 2002

So unlike many, even most, of Gonzalez-Torres’ other works, which are endlessly reproducible and renewable, Untitled (for Parkett) has a finite and dwindling existence. Unless it is installed and preserved in those sites. Which is possible. A billboard preservation network could emerge. These mostly private spaces could become the sites of public pilgrimage. Assuming they were ever private to begin with. From a 1991 interview with Bob Nickas:

Someone’s agenda has been enacted to define “public” and “private.” We’re really talking about private property because there is no private space anymore. Our intimate desires, fantasies, and dreams are ruled and intercepted by the public sphere.

installation view, venice, 2003

Though it has apparently never been written about specifically, Untitled (for Parkett) is mostly seen in reproduction, and in exhibitions. The Foundation’s exhibition history lists 14 shows, including eight exhibitions where it’s not clear if the billboard was shown, or just illustrated: three were at commercial galleries, one was organized by the Sammlung Goetz, and two were at museums. In addition to the three shows in Adelaide which included a single print, the billboard was installed in six exhibitions. I’d add a seventh, the 1997 Whitney Biennial; I remember it installed in the lobby, with the curtain of light strings, Untitled (America), hanging in front of it.

installation view, 2010, singapore

But three of the six shows, including the debut exhibition in 1994, one at MoMA in 2001, and another in 2010 at Singapore’s Tyler Print Institute, are Parkett collection shows. Parkett’s ever-growing collection of artist editions is basically on constant world tour. It’s traveled to at least seven additional venues. Their installation images are interlaced throughout this post in reverse chronological order. They show that billboard at every venue. And why not? Besides the Jeff Koons balloon toy, it’s one of their most ambitious, awesome editions.

Here’s the complete [I think] list: 149 Books, New York (1994); Louisiana Museum, Denmark (1996); MAK Center, Los Angeles (1997); London (2001); MoMA, NY (2001); Dublin (2002); Venice (2003); Kanazawa, Japan (2009); Singapore (2010); Seoul (2011). Ten installations, almost every one with different dimensions and site specific quirks, which should make reinstalling a single exhibition print impossible [as well as unauthorized].

So is Parkett churning through actual numbered editions? The A.P.’s? An undeclared stack of exhibition copies? They haven’t gotten back to me, so I don’t know. But that’s 15 installations total.

Felix did discuss the edition, , or an early conception of it, anyway, with Joseph Kosuth in 1993:

JK: This goes from the earlier idea of the collector as someone who buys knickknacks to the idea of the collector as patron. It’s a certain kind of leap that has more tod o with intellectual engagement and less to do with reducing art to nice little things in the apartment.

FGT: You know, someone once asked me to make an edition of prints. But I thought, why make an edition, why make a print? The world doesn’t need any more prints by artists. So I said no. But then I thought about it, and I said, well, why don’t we push the limits and do a billboard? The conditions are such that you can only show it in public. You have to show it in public.

Obviously, he decided to push the limit in a different direction. When Kosuth lauded his embrace and tweak of a “traditional form” and context, Gonzalez-Torres responded:

Well, my first reaction was a very predictable Leftist reaction which more and more I am questioning and finding very static and self-defeating. At this point I do not want to be outside the structure of power, I do not want to be the opposition, the alternative. Alternative to what? To power? No. I want to have power. It’s effective in terms of change. I want to be like a virus that belongs to the institution. All the ideological apparatuses are, in other words, replicating themselves, because that’s the way the culture works. So if I function as a virus, an imposter, an infiltrator, I will always replicate myself together with those institutions. And I think that maybe I’m embracing those institutions which before I would have rejected. Money and capitalism are powers that are here to stay, at least for the moment. It’s within those structures that change can and will take place. My embrace is a strategy related to my initial rejection.

I can’t tell if the market-based capitalist system is failing to realize Untitled (for Parkett), or succeeding in preserving it, in bulk, unrealized and incomplete, for the future–or both. But it is certain that Felix has successfully infiltrated Parkett, which is busy replicating his work together with their institution.

You Don’t Complete Me, Or Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (for Parkett), Part 1

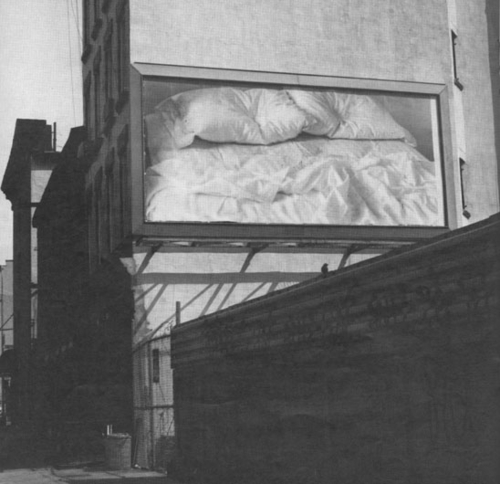

this one. Untitled, 1991, Site #21: 504 W 44th St.

One of the formative artworks in my life is set to re-appear this month. I saw one of the giant black & white billboards of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ empty bed in the city in 1992 before I realized it was part of MoMA’s Projects series. Billboards were supposed to promote something, to give you information, I thought, not to leave you wondering. Wondering what the hell is being sold here, what something as private and messy as a bed is doing on a billboard.

When I next walked into MoMA, though, and saw the same billboard, and read curator Anne Umland’s brochure for the show, I realized my encounter was exactly the kind of “illogical meeting” Felix had intended:

Rather than clipping something from the mass media and repositioning it within the clean smooth space of a work of art, he makes the photograph of the bed the informational fragment, and collages it into the broad and varied pattern of the contemporary urban landscape.

The artist has explained that by “taking a little bit of information and displaying this information in absolutely ironic and illogical meetings,” he hopes to reveal the real meaning of issues. The juxtaposition of an image that we are inclined to read as private and a space usually conceived of as public is what Gonzalez-Torres would describe as an “illogical meeting.” When we call something illogical, we are essentially saying that it runs counter to our expectations.

Umland also wrote, “Much of Gonzalez-Torres’ art questions what we mean when we describe something as private or as public.”

This public/private aspect of billboards kicked off a 1993 discussion between Gonzalez-Torres and Joseph Kosuth, both of whom, it turned out, had created billboards that, as Felix put it, “can only be shown in public. They’re privately owned but always publicly shown.”

[Kosuth:] …there were very few people who wanted to spend their money without getting some ‘goods’, you know.

FGT: Well, you opened the way for other artists. People can buy these billboards, but they have to put them in public–they have to rent a public space. It’s like buying edition prints, except that you have to put them up on billboards. It’s also doing a service to the collectors because they don’t have to put the works into storage!

Never mind that fabrication and the monthly cost of renting adspace far outstrips any storage cost. I think Felix’s point with his billboards was that he was fine delivering collectors the “goods”; but to see the goods, they have to print them up and install them in public.

All except one.

For every Felix billboard, the owner gets an image, a certificate, and the right to fabricate and install it in public any time. But for one billboard, Untitled (for Parkett) [above], Felix created his own “illogical meeting,” a work which thwarts the very expectations he set up for the rest of his work.

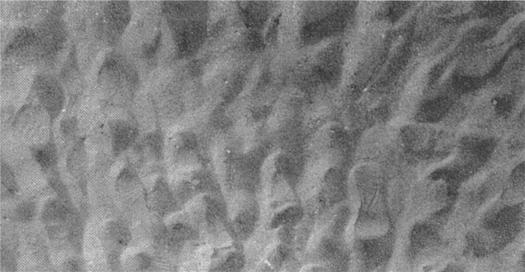

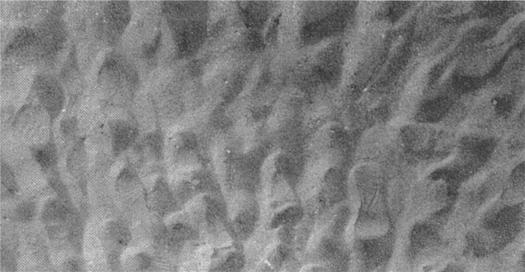

Felix created Untitled (for Parkett), in 1994 for, as the parenthetical says, Parkett’s editions series. The abstraction-like image is a black & white photo of sand churned up by footprints. It was published in an “edition of 84, 15 a.p., several exhibition copies,” and produced the same way as his other billboards are [or were, anyway], as giant silk screened sheets of Appleton coated paper that get tiled and pasted up like wallpaper.

But when they do, that’s it. They’re permanent, can’t be moved. Can’t be taken down and reinstalled. As the lot description in the Phillips catalogue last month that got me thinking about this in the first place put it,

This piece is not complete until installed. The installation site will be its permanent location until the piece is destroyed.

Now, this is not news to me. As it turns out, I have this edition. I have several, in fact, which I bought hoarded precisely because I knew that they were one-time deals, and that, like most New Yorkers, I was not expecting to be in my apartment forever. I figured I’d move someday, maybe even into a place where I could fit a 3×7-meter billboard. Then who knows, maybe I’d move again, or at least rehang the place, and so I’d need another, and so on, and so on…

But the Phillips language struck a chord in a new way. In 2007, Christie’s explained the piece a little harshly: “This work should be displayed in only one location; removal will destroy the piece.” But that’s easy, just never remove it. And anyway, that’s after it’s installed, in some distant unimaginable future. Phillips, though, pointed out the weird anomaly of Untitled (for Parkett), which is that the work, as it exists, as it’s being sold, as I have it, in fact, is incomplete.

Suddenly, I’m not a steward preserving the work; I’m an obstacle impeding its realization. And so is everyone else who bought the work, only to keep it rolled up. The people who hold it in stasis, retarding its potential, and keeping it viable and exchangeable in the marketplace.

As this description I missed in 2010 shows, Phillips’s language of incompleteness seems to come from Parkett themselves:

According to the publisher, Untitled (For Parkett) employs the materials of industrial advertising which are not meant to last indefinately [sic]. The Billboard is not water-proof. Marks and imperfections in the printing are a natural result of the printing process and are part of the image. Bubbles or wrinkles remaining in the paper after installation are an expected and acceptable part of the finished work. The billboard is designed to be installed either indoors or outdoors. Like most of the artist’s works installation is an integral conceptual part of the work, and is considered incomplete until then.

Not only are you depriving the work of its destiny by not installing it, it’s not going to last anyway.

And that auction catalogue blurb turns out to be just about the longest thing anyone’s ever published on Untitled (for Parkett) before. So I started poking around a bit. [to be continued]

On Repainting Gerhard Richter

First, Happy Birthday, Mr. Richter.

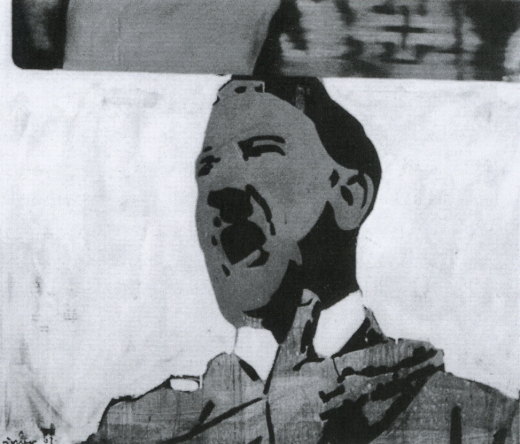

Destroyed 1964 Richter painting, image from Gerhard Richter Archkiv via Spiegel

I don’t know if Joerg knew at the time he first tweeted about it–he is plugged in and German, so who knows?–but I certainly had no idea when I picked up on the topic of Gerhard Richter “destroying” paintings by painting over them. But it turns out that the 74 paintings listed as “[DESTROYED]” on Richter’s website are only a fraction, barely half, of the paintings he’s actually destroyed so far.

In an interview with Ulrike Knöfel for Spiegel, Richter talks about the 60 or so photo-based paintings he destroyed in the 1960s during a very self-critical period of his career. Not to worry, though, because, being Gerhard Richter, he photographed them first

These photos, most of which were never published, are now either in the Gerhard Richter Archive in the eastern German city of Dresden, where the painter was born, or in a box in his studio in the western city of Cologne. They are testaments to his refusal to compromise.

Mhmm. Though the ambivalence/regret/equivocation Richter expresses in the interview reveal that a refusal to compromise is not automatically a win. Couldn’t he have just put them away and not looked at them for a while instead?

None were apparently included in Richter’s first catalogue raisonne, the source for his website’s “[DESTROYED]” list. And many appear to date from the earliest phase of his recognized work, 1962-4. Oh but wait, his much-discussed 1962 Hitler IS online, described as “believed to have been destroyed.”

Hitler, 1962, image via gerhard-richter.com

That seems like a new category, loaded with ambiguity. I like it much better than “[DESTROYED]” or even “Richter painted over this work in ___. The painting is now entitled ____.” Which, it turns out, has another example:

Today, Richter says he’s surprised at how many works he continued to destroy after the 1960s. Perhaps he will return to one motif or another, he adds, noting that “otherwise it would be a shame.” One painting, in particular, comes to mind. It was painted in 1990 and shows two young people standing in front of Madrid’s Museo del Prado, Spain’s national art museum. However, two years later, he painted over this work, turning “Prado, Madrid” into “Abstract Painting, 1992.”

Which, yeah, there is no Prado, Madrid in the CR, and there are at least 279 Abstraktes Bild done in 1992, so, this’ll take a bit of digging. I’ll update the post when/if I find it. [I’ll have to do an update post anyway, because I’ve already found at least two other overpainted paintings.]

This painting over thing is one thing. The other, which I’m kind of fascinated by now, is the relationship between painting and photography as it plays out in these destroyed paintings. Which, of course, still exist as the artist’s photographs. It’s like Barthes’ Camera Lucida; they’re gone, but not. I can’t tell if this is Spiegel’s interpretation or reportage:

Still, since his urge to destroy some of his paintings also made him feel uneasy, he photographed them before doing so.

But someone has to have already looked at this backup, insurance, documentary, archival, post-mortem, forensic, ghost aspect of the way these two mediums intertwine. Right?

Photo of destroyed Gerhard Richter painting, 1960s, by Gerhard Richter, image: Gerhard Richter Archiv Dresden via Spiegel

Meanwhile, the obvious thing–and isn’t that what I’m here to point out?–is to recreate these destroyed Richters. Whether you paint the archival photo, crop marks and background and all, in a meta-Richterian gesture, or just try your darnedest to bring their destroyed, painted subjects back to life, I’ll have to figure out. But paintings based on a painter’s photographs of paintings based on photographs? What’s not to love?

It’d be trivial to the point of meaninglessness to just print the Spiegel jpgs on canvas, or to order them up from Chinese paint mills. But I’d be interested to see just how much more meaning could be gleaned by painstakingly copying them by hand. Even if the answer is very little, that’s still an important datapoint.

His Own Harshest Critic | A New Look at Works Destroyed by Gerhard Richter [spiegel.de via bigthink]

Overpainted Gerhard Richter Painting

Joerg tweeted last night about a “[DESTROYED]” 1982 Gerhard Richter candle painting, and heeyeahsure, I’ll look at that.

It turns out though, that the artist’s own term is not entirely accurate. Because according to his website, the painting, 2 Candles 1982, (CR 499-3), still exists: “Richter painted over this work in 1996. The painting is now entitled Abstract Painting (CR 837-4).”

l: 2 Candles, 1982-96 state; r: Abstract Painting 837-4, 1996-, images via gerhard-richter.com

Which would be interesting enough if it were a one-off thing. And no, it appears that Richter has not painted over any of the 73 other paintings listed as “[DESTROYED]”. But by 1996, he had already been painting on photographs for a decade. In 1989, in fact, he produced two editions of candle images overpainted with squeegees.

Candle III, 1989, ed. of 30+10, image: gerhard-richter

There are at least a dozen other such editions since then which combine photos or photoreproductions and squeegeed abstract overpainting. They constitute a persistent connection between the two seemingly diametrically opposed bodies of Richters’ work: photo-based representation and so-called aleatoric, or mechanized, gestureless abstraction. It’s a dichotomy that continues to stump even the illustrious Benjamin Buchloh, who laments while writing, at great length, in the latest Artforum: “The question posed over and over again (and which has basically remained unanswered) was how these photographic images could be related to the emerging works of abstraction.”

But my bigger point here, which Buchloh also cursorily notes, as does anyone who’s seen Corinna Belz’s film Gerhard Richter Painting, is that overpainting is central to Richter’s abstract practice. In these stills from the scene that appears in Belz’s original trailer, Richter very thoughtfully creates classical gestural abstractions:

Which remind me of nothing so much as the great, underappreciated-until-just-now, large-scale paintings of Willem de Kooning from the mid-1970s.

It’s one of the main reasons I hustled back to MoMA to see the de Kooning show on the last day, after seeing Belz’s film, and after getting both the Richter and de Kooning catalogues for Christmas. Because these amazing wet-on-wet structures that Richter laid down

felt almost like reincarnations of some of the virtuoso brushstrokes de Kooning made in 1975 paintings like Screams of Children Come from Seagulls [check out this dark blue, sideways L from the upper right quadrant, for example]

or the single, epic loop at the center of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Untitled XI (1975):

And then when they’re just right, Richter takes his squeegee to them. As if getting erased by Rauschenberg wasn’t enough.

But–oh man, I really did just mean to do a quick, “ooh, look, overpainted Richter!” post here–but this is the thing that bugged me so bad about Buchloh’s reading: his extraordinarily limited range of references in discussing Richter’s work. I mean, it’s basically Johns and Stella [Stella!]. And he dismisses Johns on false pretenses. And doesn’t mention de Kooning once.

Here’s what Buchloh got from Belz’s film–WHICH HE WAS IN: some kind of Surrealist theatrical something or other:

Starting the production of each canvas with strange rehearsals of various forms of gestural abstraction, as though moving through recitals of its legacies, in the final phases Richter seems literally to execute the painting with a massive device that rakes paint across an apparently carefully planned and painted surface. Crisscrossing the canvas horizontally and vertically with this rather crude tool the artist accedes to a radical diminishment of tactile control and manual dexterity, suggesting that the erasure of painterly detail is as essential to the work’s production as the inscription of procedural traces. Thus an uncanny and deeply discomforting dialectic between enunciation and erasure occurs at the very core of the pictorial production process itself, opening up the insight that we might be witnessing a chasm of negation and destruction as much as the emergence of enchanting coloristic and structural vistas.

Alright, so maybe it’s not that wrong. No, it is, because after 20 years working on layers and layers of paint with that “crude tool,” Richter has proved, I think, that he has all the control he needs.

Just as Rauschenberg’s erasing were not negation, but creation through another type of mark, I think Richter’s squeegee strokes are generative additions to, not killers of, the rich repertoire of markmaking techniques he inherited. Maybe it took Belz’s film to show how tightly the squeegee marks are linked to Richter’s body and movement. They don’t diminish, but magnify; they’re full-body gestural abstraction.

For a great illumination of the specifics of Richter’s abstract production, I keep going back to Tate Modern conservator Rachel Parker’s discussion with blogger Mark Godfrey during the Panorama show:

If we think about the very large scale of Wald 3, we must consider the logistics of one man making this painting. Although Richter probably dragged the squeegee across the wet surface in two separate applications this process must have demanded enormous physical energy. The two resulting squeegee tracks are obvious: one track extends from the top to about 5/8 of the way down the painting surface and the other starts just below this. It would appear that Richter applies the squeegee first to the left side of the work and then drags it from left to right: with both tracks he appears to stop ¾ of the way across for a rest before completion. You can also tell exactly when the momentum of dragging the squeegee across the very tacky surface began to slow down as the drag marks become more shallow. The upper track is characterised by the squeegee having embedded itself more deeply into the paint resulting in slightly sharper surface disturbances and deeper excavations. The lower track has glided more fluidly across the surface creating lighter disturbances. There is undoubtedly an element of chance in the results of this technique: the first track will bear most influence on the final composition whereas with the second track, Richter tries to replicate the same direction, speed and weight behind the squeegee to re-create the same marks in the paint. The compositional balance between track 1 and track 2 in Wald 3 exposes Richter’s trust in his materials and intuitive craftsmanship.

I’ve got more bone to pick with Buchloh’s analysis, which ultimately fails to convince because it seems so disengaged, so cut off within the hermetic, Richterworld bubble. But maybe later.

Because Parker and Godfrey make a very persuasive case, I think, for some of the implications of Richter’s overpainting,. In this case, they discussed SFMOMA’s 1999 Abstract Painting (CR 858-6) [above] on aludibond panel:

Richter has applied his paint in a similar manner as before, manipulating the paint with a squeegee when the paint is very newly applied, hence its fluid character…Once the paint has dried Richter has taken a sharp wide-head palette knife and gouged and scraped features out of the paint layer, exposing the paint-stained white preparatory layer beneath. The technique creates a hallucinatory effect (are the shapes portals or are they solid elements floating in a multi-dimensional composition?).

These underlying paintings aren’t destroyed; they just become something else.

UPDATE: Alright, I’m righter than I knew. There are at least three more overpainted paintings.

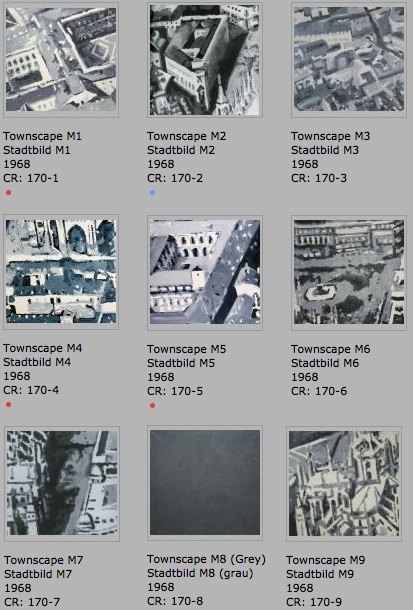

Stadtbild M1-M9, 1968, rearranged into a 3×3 grid, image: gerhard-richter.com

The earliest known example is from the Stadtbild/Townscape series, from 1968. Richter first created a large, 2.7m x 2.7m painting based on an aerial photograph of the center of Milan, which he then cut into nine nearly square paintings, numbered M1-M9. Townscape M8, however, he painted over with grey [above]. Joe Hage, the collector/technologist/uber-groupie behind Richter’s website notes:

Townscape M8 depicted what was presumably a detail taken from the same source photograph and was painted over with grey paint later.

…

The series Townscapes M1 up to M9 illustrates Gerhard Richter’s engagement in the process of abstraction: starting from a concrete depiction, which was enlarged at first and then cropped, the final image can barely be traced back to the source photograph. The numbering of the single parts of the painting, which do not relate in any way to their initial positions in the original large format, also suggests that any kind of identification is less important to Richter than the painterly process of abstraction.

So in this case, at least, there is currently only the presumption of underpainting, based on the series, the title, and the procedure of its making.

Hanged and Blanket, both 1988, via gerhard-richter.com

The next example, though, is the opposite. While painting his October 18, 1977 series in 1988, Richter made two identically sized versions of Hanged [above, left], only to partially paint over one and retitle it, Blanket, after the blurred photo-based image that remains visible under the squeegee. The CR numbers show that Blanket [680-3] was completed some time after Hanged [668], with at least two dozen squeegee paintings in between [including two “[Destroyed]” works]. After evoking the “function of a curtain in art history: a painted curtain indicates that a glance is allowed at something that should not necessarily be seen,” Hage’s note offers an interpretation of this overpainting: “It appears almost as if Richter wanted to shield the events from view, by painting over the second version of the painting almost completely.” Which would be true enough in isolation, but which seems to mean not considering the existence of the un-squeegeed version. Which is nevertheless blurred, as if there’s a continuum of obscuring and revelation.

The third example comes from the Spiegel story on Richter’s destroyed paintings. Ulrike Knöfel writes of a work

painted in 1990 [which] shows two young people standing in front of Madrid’s Museo del Prado, Spain’s national art museum. However, two years later, he painted over this work, turning “Prado, Madrid” into “Abstract Painting, 1992.”

There’s no Prado related work mentioned on the side, but there are two Atlas pages of photos from Madrid. I’m still looking through the 279 108 abstract paintings from 1992 to see if I can figure out which one it is. update from a few minutes later: no idea.

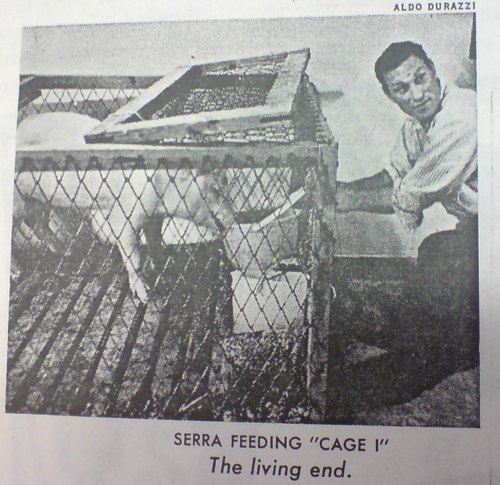

Serra ‘Designs His Works To Last.’

Well this certainly wasn’t in his MoMA retrospective.

There are rubber and neon pieces dated from 1966-7, of course, and because they look prescient now, Benjamin Buchloh’s catalogue essay discusses early Richard Serra sculptures like Doors and Trough Pieces as “the official beginning of his oeuvre.” But Buchloh dismisses Richard Serra’s first solo show in May 1966 in Italy, where the young artist was traveling on a Fulbright, as nothing but “his rather literal responses to Rauschenberg’s combines.” Fortunately, the show got written up–with a picture, even–in Time Magazine:

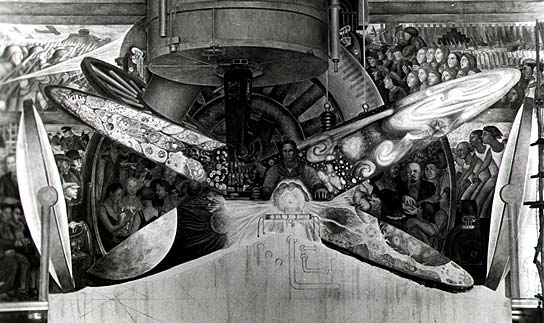

Lucienne Bloch’s Muralphotos

I didn’t realize how closely the Modern’s 1932 Murals and Photomurals exhibition and the anti-communist controversy it provoked dovetailed with the far better known confrontation over Diego Rivera’s rejected and destroyed commission at Rockefeller Center.

Rivera had a hugely successful one-man show at MoMA in 1931. Lincoln Kirstein’s exhibition of murals by American artists was, as he said in the catalogue, “Stimulated in part by Mexican achievement, in part by recent controversy, and current opportunity.” The recent controversy, it turns out, was a January 1932 protest by art students from the New School, who objected to reports that John D. Rockefeller Jr. had selected foreign artists, Rivera and Jose Maria Sert, not Americans, to paint murals in Rockefeller Center. Check out this incredible NYT headline:

WANT NATIVE ART IN ROCKEFELLER CITY; Students Protest on Hearing A Report That Rivera and Sert Are to Paint Murals. ARTISTS NOT YET CHOSEN Architect Promises Citizens Will Have an Equal if Not Better Chance for Commissions. FOREIGNERS CRITICIZED Class at School for Social Research Declares Selection of Any Aliens for Building Here “Inconsistent.”

Which means the Modern’s show, which came together in a matter of weeks, was more an attempt by the Rockefellers to blunt nativist criticism in the wake of a Rivera lovefest as it was a helpful promotion of the work of American artists for anyone who might find himself in the market for a few thousand square feet of murals. [And for the record, ascribing this decision to the Rockefellers and not the Museum per se is fine; the show originated in the Advisory Committee, headed by the 23-yo Nelson Rockefeller.]

But this also means that trustees’ objections to anti-capitalist-themed works, and the ensuing threats of a protest and boycott by a dozens of artists in the show, did not happen out of the blue; they occurred in the context of the Depression, where anti-foreign sentiment was as readily expressed as anti-capitalism. And more to the point, it happened in and around a Museum founded by the family that was the symbol of capitalism, who was in the middle of one of the largest building projects in history.

And sure enough, that fall, Rivera was announced as John D. Rockefeller’s pick for a fresco in the complex’s flagship, the RCA Building. It can’t have been a naive decision. The day after Rivera arrived to begin work on the Rockefeller Center mural, his just-finished mural cycle at the Detroit Institute of the Arts, Detroit Industry, came under attack for “blasphemy.” [The DIA had invited local religious leaders to comment on it, and because one small panel in the upper corner depicted a swaddled baby being vaccinated by three wise scientist men, some clerics demanded the work be destroyed. Go figure.]

The Times kicked off its play-by-play coverage of the project by “the fiery crusader with a paint brush,” by noting “DIEGO RIVERA is again the centre of a raging controversy. and his new job at the RCA Building in the Rockefeller Center is likely to provoke another.”

And sure enough, less than three weeks later, after it became clear that that was no random baldheaded, goateed man in the center of Man At The Crossroads with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future, but Lenin himself, Nelson Rockefeller was called in to persuade Rivera to genericize the figure. Rivera refused, and he was quickly paid off and barred from the premises. Eager to not have the nearly-completed work photographed, the Rockefellers first covered it with drapery, and within a day, had covered it with canvas. After unsuccessful attempts spearheaded by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, John D’s wife, to salvage the mural, perhaps to put it in the Modern, it was destroyed. Which prompted workers to protest anew in April 1934.

Now I knew it was a controversy, but I had no idea how heated and seat-of-the-pants the whole situation was, nor what a spectacle. It was on the front page of the Times for days, weeks, even. I also didn’t realize how incredible it was that Lucienne Bloch managed to take the only photos of the mural before it was covered up. Bloch began working as Rivera’s assistant after she was seated next to him at the Modern’s 1931 opening dinner.

The whole photo drama was retold [with perhaps a bit of anti-capitalist gloating?] in Bloch’s obituary in 1999:

Lucienne Bloch, an acclaimed muralist whose most significant contribution to art may have been a series of surreptitious photographs she took in 1933, died on March 13 at her home in Gualala, Calif. She was 90.

She was the photographer whose sneak pictures taken behind enemy lines on May, 8, 1933, are the sole visual record of the great Diego Rivera’s ill-fated Rockefeller Center fresco with its doomed depiction of Lenin.

At a time of economic distress, when capitalism itself seemed vulnerable to competing currents of social change, if anybody was going to pin Lenin on a capitalist wall it was Diego Rivera, the fiery Mexican muralist whose artistic acclaim was matched only by his reputation as a fiercely committed, if renegade, Communist.

If anybody was going to stop him it was John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s son, Nelson A. Rockefeller, who had commissioned Rivera to paint a 1,000-square-foot fresco, ”Man at the Crossroads,” in the great hall of the new RCA Building, the soaring Rockefeller Center capstone now known as the G.E. Building and at the time an especially potent symbol of capitalism.

Rivera used Bloch’s photos to recreate the Man at the Crossroads later in Mexico City.

Beginning With Anne Truitt’s Japanese Works

I hear blogging is out, everyone’s tweeting or facebooking now. While I don’t quite buy it, I am finding that I’m more likely to keep something I find interesting in my browser tabs for months rather than post it straightaway.

I will now attempt to clear those tabs to the general amusement and edification of my readers:

Soon after her first solo show at Andre Emmerich, Anne Truitt followed her then-husband James to Japan for several years. While there, she experimented with making sculptures from aluminum. She showed them at Emmerich, I believe in 1966, but was not pleased with them, and rather famously destroyed them all before her mid-career retrospective at the Corcoran in the early 1970s. Had them all crushed like a soda can. All but two, apparently.

According to Kristen Hileman’s catalogue, there was an aluminum Truitt in the collection of the Trammel Crow corporation, which could not be found, and another in the collection of a Connecticut collector whose name escapes me [and my Truitt catalogue is in our other apartment, alas.] Anway, that one was apparently damaged or destroyed by exposure, it’s not clear.

I’d never seen images of these lost works, but then suddenly, I stumbled across one on the excellent Los Angeles-based art and space blog, You Have Been Here Sometime.

It turns out to have come from the official site, annetruitt.org, which is a great thing to know about. The piece is called Out and dates from 1964. There are other Japanese works, and also installation shots from the Emmerich show. More geometry and fewer right angles than in Truitt’s later work, enough to make me wonder if the artist had issues with form, not just paint, light, and color, as she explained.