Untitled (Andiron Attr. to Paul Revere, Jr.), 2015

It’s not an easy thing, to meet your maker.

– Roy Batty, Blade Runner

Saturday I went to the Metropolitan Museum to see their installation of my piece, Untitled (Andiron Attributed To Paul Revere Jr.), which until now I’d only known from photos.

I think it’s the one on the right.

The thinking this work has generated for me is immense and entertaining and rather ridiculous. Even in a week when Danh Vo sold basically an entire visible storage unit of Martin Wong’s stuff to the Walker as his own installation.

Danh Vo, I M U U R 2, detail, 2013, 4,000 objects and artworks from the estate of Martin Wong, image: Walker Art Ctr via TAN

Vo showed Wong’s collection and artworks as his Hugo Boss Prize exhibition at the Guggenheim, but he turned it into an artwork in order to save it, to prevent Wong’s ailing mother from being forced to sell and disperse the collected objects at a garage sale. As The Art Newspaper put it, “Vo got the idea of turning it into an installation from a curator who suggested that would increase the chance a museum would acquire it.”

Which technically means I M U U R 2 moved in the opposite direction fromUntitled (Andiron &c.), which was a decorative collectible embedded deep in a museum, and turned into an artwork in order to, uh…

I still don’t know. And of course, I wasn’t thinking of this specific relationship on Saturday, but more about the presence of the andiron’s unknown/unphotographed twin, and which was which. Did they have their accession numbers painted underneath? I was thinking about their attribution, and what it’s based on, who made it, how did they compare to the actual [sic] Paul Revere andirons nearby? I thought about that pedestal which, when I started to move it to take a cleaner picture, turned out to be a fire extinguisher cover, so I left it alone.

How nice their location is–in one sense–on the end, near a wide aisle, right by the doorway, and how crappy it is in another–it’s around the corner of a dead end corridor, through a darkened vestibule lined with fireplace mantles. It really might not be that different from the Lexington Ave. antique shop where I imagine Mrs. Flora T. Whiting first buying them. How far they’ve traveled, and yet almost not at all.

It reminded me of the Costume Institute, and how it was set up to accept the tax-deductible donations of last year’s fashions from Nan Kempner and whomever. The Met’s functioned that way a lot, as the hallowed dumping ground of New York’s ruling class. If the Smithsonian is America’s Attic, the Met is the Upper East Side’s. The soft underbelly of the late Met curator William Lieberman’s professed strategy to “collect collectors,” not paintings. [Actually, huge swaths of the Met’s 20th c./Contemp. collection reflect the same “We’ll take it all!” spirit. But that’s for another day.]

There’s a lot of room between museum quality and garbage: studies, archives, and visible storage collections to the left; destroyed works, misattributions, and garage sales to the right. And value in its various forms accrues accordingly. To the extent that they rejigger these value tallies within the museum-object-author-viewer relationship, I guess I M U U R 2 and Untitled (Andiron) are not opposites at all.

Tag: destroyed

Some Other Art At The 1964 New York World’s Fair

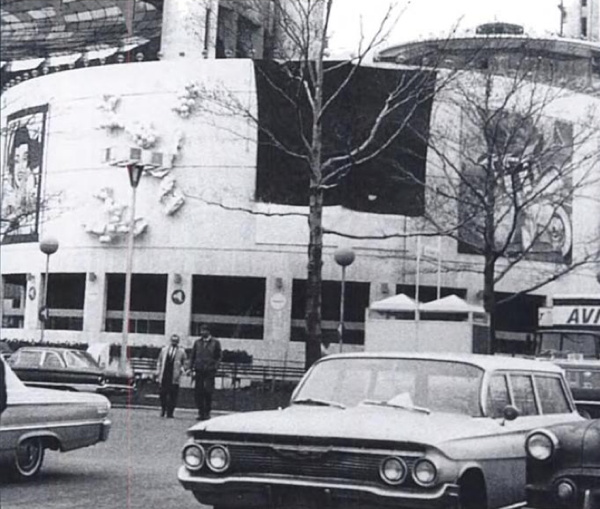

Thirteen Most Wanted Men overpainted and covered by tarp, 1964. Photo: Peter Warner, via Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation

From the amount of attention it gets, you’d think Andy Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men was the biggest art deal at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. And it wasn’t even there for more than a couple of days.

But there was actually other art in the fair, and organizer Robert Moses was not into it. Countries could show art if they wanted, of course–Italy brought Michelangelo’s Pieta, and Franco’s Spain brought some El Greco. But Moses rejected petitions for a dedicated art exhibition at the fair, and he intervened in at least one other situation besides Warhol’s to nix art that attracted criticism. I’ve dug around a bit in the New York Times’ coverage of art and the fair, mostly from the cranky conservative critic John Canaday, and it has broadened and definitely complicated my view of the era, the venue, and the outsize parties involved.

If you do nothing else, read Canaday’s various acidic takedowns of the consumerist banality and kitschy circus of the World’s Fair, and how Art shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same breath. His column, “The Fair As Art,” tries to stretch the definition of folk art to cover the what we’d now recognize as late capitalist spectacle, and it’s interesting how he can’t quite get the nascent Pop Art movement to sync up with the populist source of its content.

No, first read about Canaday’s Feb. 1964 evisceration of the announcement that Tomorrow Forever would be the “theme painting” the Hall of Education. The landscape was filled with the trademark Big-Eyed Children of Walter Keane, the Thomas Kinkade of his day, who, it turned out, couldn’t paint a fence, and instead passed his enslaved, abused wife’s paintings off as his own.

This extraordinary profile of Margaret Keane in The Guardian yetserday led me to Canaday’s review. [Tim Burton’s biopic of Keane comes out in a couple of weeks.] But the piece also says that “Stung by the review, the World’s Fair took down the painting.” Actually, Tomorrow Forever never made it into the fair. Robert Moses intervened almost immediately after Canaday’s attack, more than two months out from the opening, saying, “The fair does not censor exhibitions except in cases of extreme bad taste or low standards. This was such a case.”

[Ouch. Moses’s willingness to boot one reviled painting makes his central role in the Case of the Destroyed Warhol Mugshots seem all the more plausible. For his part, Warhol praised Keane and his outsized commercialism. LIFE Magazine asked Warhol about Keane in 1965: “It has to be good,” he said. “If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.”]

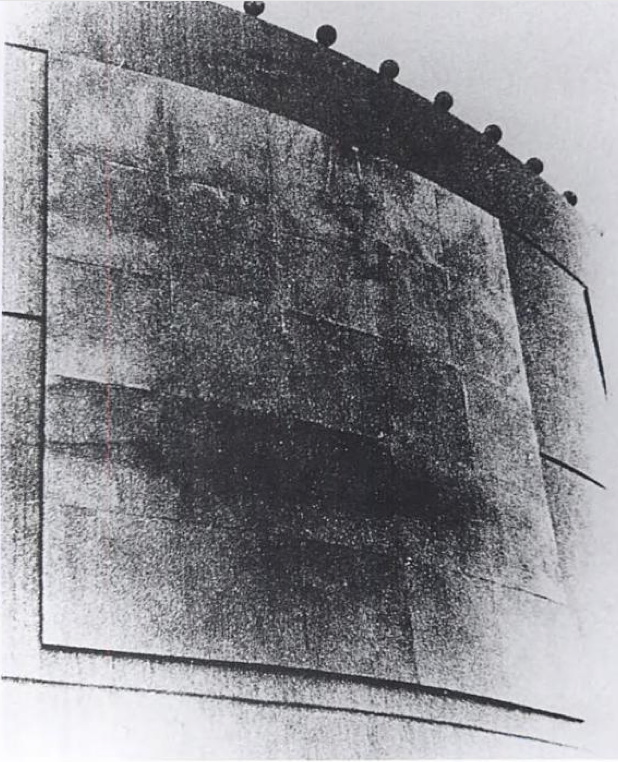

Anyway, Warhol’s World’s Fair piece can’t have been too much of a surprise. Though his name is misspelled, “13 Wanted Men” is mentioned by title in a NYT report from October 1963, “Avant-Garde Art Going To Fair”. The other nine artists Philip Johnson commissioned are also listed, and I realized I never registered that Ellsworth Kelly had been involved. But he produced a work on painted aluminum.

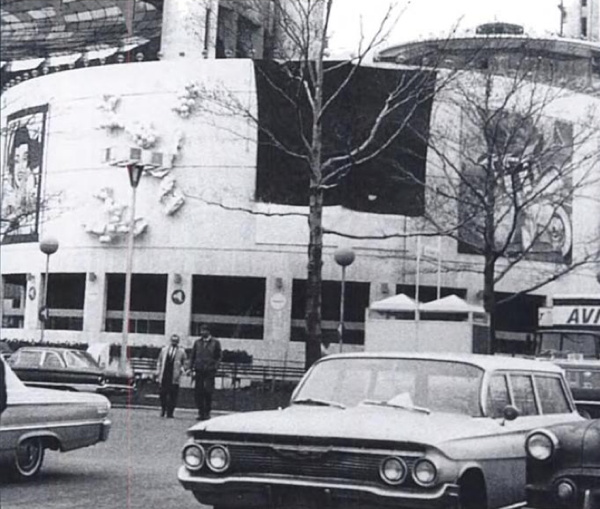

And here it was. Untitled at the time, Kelly’s 18-foot curves projected from the wall of the New York State pavilion, where they were installed next to James Rosenquist’s mural, which was next to Warhol’s. Except the Rosenquist is either covered or gone in this Nov. 1966 photo from World’s Fair enthusiast Randy Treadway. So is Robert Indiana’s EAT, which was on the right of Kelly.

A bunch of the NYS Pavilion pieces ended up in the Weisman collection at UMinn., but in 1967 Johnson apparently donated the Kelly to Harvard, where it was known as either Two Curves or Blue Red. In 2001, a campus-wide survey of culturally important objects found “Blue Red” on the side of the parking garage at Peabody Terrace. The super was about to repaint the deteriorated sculpture with Rust-o-leum when conservators intervened. The Google Streetview image from this summer [above] shows it looking much better.

So Different, Yet So Alike

I know it’s folly to take auction catalogue text as art history, but it is of a piece, at least in this case.

Untitled, recto, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, image: Sotheby’s

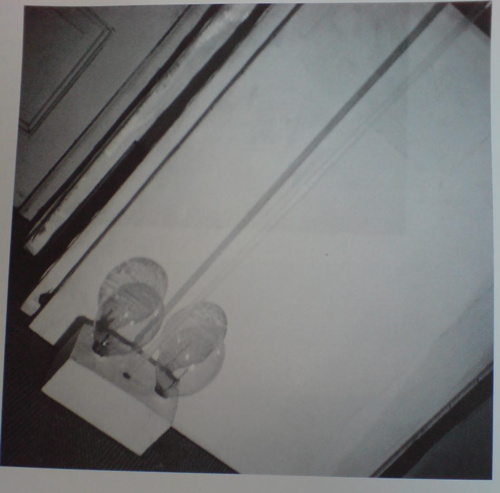

Last night’s sale at Sotheby’s included a very early, underdocumented 1954 combine by Robert Rauschenberg, which he gave to the dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor a decade later. [I say underdocumented because I can’t find any mention of it in Paul Schimmel’s otherwise exhaustive Combines catalogue, or anywhere online not associated with the auction.]

Untitled, verso, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, that polka dot fabric turns up on at least six other combines, including Short Circuit, image: Sotheby’s

The piece is freestanding, tabletop-size, with a double-sided painting/collage mounted on what seems like a 2×4 wood base. There’s a lightbulb sandwiched in between the support slats, and a pair of radiometers, those little gadgets with black & white panels that spin when exposed to light.

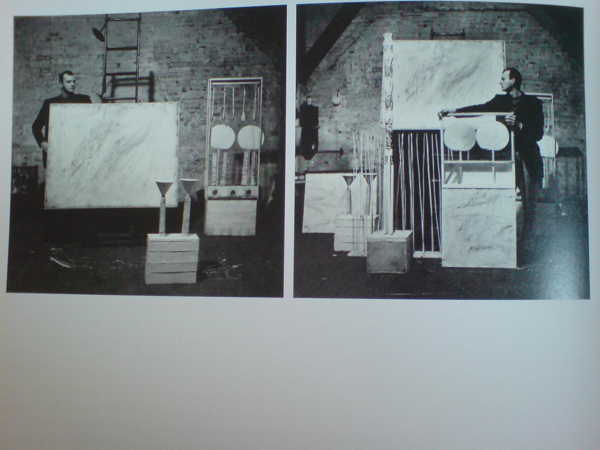

The Man With Two Souls, 1950, photographed by Rauschenberg in 1951 in his UWS apartment, where Twombly told Walter Hopps he’d seen it. He later got it. image: Hopps’s Rauschenberg: The Early 50s

As soon as I saw it, I thought of Rauschenberg’s earliest surviving sculpture, made in 1950. Cy Twombly got it after Rauschenberg’s 1951 show at Betty Parsons, but before he and Bob took off for seven months to Africa, leaving Susan Weil and the baby behind. The piece is called The Man With Two Souls, and it consists of a glass rod flanked by a bulbous pair of wine bottles inserted in a cast plaster block. Charles Stuckey suggested it was an homage to Barnett Newman’s sculpture Here I, which was shown at Parsons earlier in 1951. Yes, that might be one allusion.

Twombly and sculptures in Twombly’s studio, 1954, photographed by Rauschenberg, image via Schimmel’s Combines

It also might be similar to almost every Cy Twombly sculpture in these photos Bob took in 1954, the year Taylor’s combine was made. The year, in fact, when Rauschenberg made what’s considered the first of his combines, set pieces for Taylor’s debut as a choreographer after leaving Merce Cunningham’s company in mid-1954.

And depending on which side you’re looking at, Taylor’s piece looks an awful lot like Minutiae, the free-standing set piece Bob made for Merce’s December 1954 performance at BAM. Which is all set up for my complaint about Sotheby’s catalogue text, which acknowledges that Rauschenberg was “informed by the influences” of his contemporaries like Jasper Johns, and then immediately distances the two artists:

Though their practices were fundamentally at odds, both conceptually and aesthetically, the two men supported each other’s stylistic experimentation during this critical time of immense growth and evolution.

Unfathomable difference has been the starting point of any discussion of Rauschenberg and Johns’ early work since at least 1963, when Allan Solomon gave them each one-man shows at the Jewish Museum. It’s a presumption of separateness that shuts off any exploration of similarity, much less exchange or collaboration. And especially in the case of Rauschenberg and his artist/partners, it heads off any questions of joint creation or shared authorship.

Minutiae, made with help from Johns in time for Merce Cunningham’s Dec. 7 1954 performance at BAM

Johns has said publicly he worked on Minutiae. Twombly drew on Rebus and who knows what else. Johns even said he made a Rauschenberg with Bob later signed, and that he came up with the term “combine.”

But whether it’s historic or persistent institutionalized homophobia, emotions & ego, the demands of the market, or the lone genius paradigm of the times, it’s apparently still impossible to ask if there are similarities or connections between these artists’ contemporaneous work.

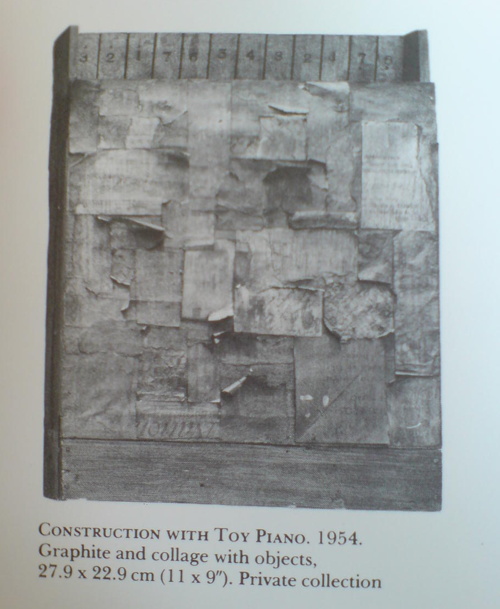

Construction with Toy Piano, 1954, image: Michael Crichton’s Jasper Johns

Twombly and Rauschenberg are both gone, alas, and Johns doesn’t seem too interested to elaborate, seeing as how he has systematically hunted down and destroyed his own work from before 1955. But at least one piece that survives, Construction with Toy Piano, a book-sized wooden object covered with painted collage, looks like it could have been made in the same room as Paul Taylor’s combine, if not by the same mind or hands. Just asking the question.

Wade Guyton And Anxiety In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction

Personally, the thing I remembered about Carol Vogel’s puff piece a couple of weeks ago for Loic Gouzer, organizer of “If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday,” Christie’s Edgy Sale, was that she’d used the word “seminal” twice in one sentence. But if I were an artist whose painting was being used as Exhibit No. 1 to illustrate it, I could see how the headline might catch my eye, too: “For Those Who Can Afford It, Christie’s Is Selling Anxiety”.

The sale was supposed to be a “mould-breaking auction,” a “risky operation” meant to “shake things up” with artworks that “capture the raw angst” that the current “generation of rich embryonic collectors” are all hot for.

image: burningbridges38/s IG

Christie’s own idea of raw shakeup: a promotional video skateboarding video, showing skate pro Chris Martin tooling through the galleries and the back of the house, passing works and staff along the way. It was the most brilliantly ridiculous thing ever. For a day. Then someone pointed out embryonic auction star Parker Ito’s own YT videos of his skateboarding around his studio. And someone else ran the numbers and realized that many lots were presold via third-party guarantees/irrevocable bids, so the actual angst of the evening’s outcome depended entirely on one’s own market ignorance.

image: @burningbridges38’s IG

Until Wade Guyton entered the game. Wade’s 2005 painting Untitled (Fire, Red/Black U) had a starring role in the sale, the video, and the Anxiety article. And last week, as the video racked up views and scorn online, Wade introduced some real anxiety–by making more than a dozen new paintings, identical to the one at Christie’s, using the same digital file. He then posted the images to Instagram. They stream out of his trusty Epson inkjet printer, are strewn across the studio floor, and flutter in the breeze like a fiery curtain on the wall.

When she declared a slightly bent & restored aluminum painting destroyed last year Cady Noland reprogrammed all her remaining work, instilling collectors with the fear that the tiniest nick or bump might render their precious object unsaleable. Similarly, by revealing even the hypothetical existence of infinite digital replication–so far, all he’s done is post pictures of canvases to Intagram–Guyton has stripped away the presumption of uniqueness, and has seized his work back from the outsized speculative frenzies that swirl around it. And the greatest part is that he did all this just days before the big sale [where he doesn’t have anything to win, and much, potentially, to lose].

As Jerry Saltz wrote, “Whatever happens tonight, I admire an artist willing to tank his own market by flooding it with confusing real-fake product.” And except that there doesn’t need to be anything fake at all about the resulting works, I completely agree. This is awesome. [Even though it didn’t slow down the sale one bit: Untitled sold for $3.5 million, a record. So win-win, depending on what actually qualifies as a win here.]

On Warhol And The World’s Fairs

If I ever get a PhD it will be in the US Pavilion at Expo67 as a gesamtkunstwerk. So much going on there, and in my years of fascination and study of it, it just keeps on giving.

And I am stoked for the Queens Museum’s show, opening to day, on Thirteen Most Wanted Men, Andy Warhol’s short-lived commission for the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. It sounds amazing, with an impressive amount of archival research and new understanding.

I haven’t seen it yet, but I have been bothered by a line that’s cropped up in several reviews of the show, which makes me think it’s not accidental, calling the 13 Most Wanted Men panels “Warhol’s only public artwork.”

This characterization only holds up if you define public art so narrowly as to make it irrelevant [which is something that happens to public art a lot, actually, but that’s not the point here.] Warhol exhibited work in at least three World’s Fairs in a row–1964 in New York, 1967 in Montreal, and 1970 in Osaka. And the first two were commissions. In fact, I’d suggest that the New York and Montreal projects are so similar, that they really should be considered together. Warhol’s Expo 67 works suddenly feel like a direct response to the controversy in 1964. When faced with the prospect of wading into another political conflict over his subjects, Warhol chose to depict himself.

In 1964, Warhol painted 25 panels–22 with mug shots, 3 blank/monochromes–on 4-foot square masonite panels. The images came from an internal NYPD pamphlet that gave the piece its title: 13 Most Wanted Men. These were painted over in aluminum house paint within two days.

Thirteen Most Wanted Men overpainted and covered by tarp, 1964. Photo: Peter Warner, via Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation

Later they were covered with a large tarp. They have since been lost or destroyed. In his incisive 2002 history, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art, Richard Meyer quotes John Giorno’s story about the origins of Thirteen Most Wanted Men, and that the mug shots came from the gay cop boyfriend of another painter, Wynn Chamberlain. 1 [No one’s mentioned it, but I assume this is all in the Queens Museum show. Right? And the show will surely explain why Philip Johnson told Warhol in 1963 not to talk about the sources of the paintings? Johnson, who surely knew as much about power, rough trade, and a man in uniform?]

Warhol painted 25 panels with Robert Moses’ headshot, taken from Life magazine, as replacements. Philip Johnson rejected them, and they are also now considered lost or destroyed. [This photo is by Mark Lancaster, who helped Warhol make the Moses panels and much else. There’s a great interview with Lancaster at warholstars.org.]

During the Summer of 1964 Warhol reused the screens to create paintings on canvas of the 13 Most Wanted Men, which Lancaster cropped and stretched. Nine of these are currently in the Queens Museum show.

In 1964 he began making the Screen Tests, which were inspired both by the Thirteen Most Wanted mug shots and the photobooth pictures Warhol began using in 1963. He created Most Wanted series of women and boys as well.

Warhol visiting Expo 67 with the de Menils, that’s John de Menil at left, not Buckminster Fuller, as some online sources would have it. image via menil.org

In 1967 curator Alan Solomon commissioned Warhol to make large paintings for the US Pavilion at Expo 67. Warhol created eight giant Self-Portraits. They are 6-feet across and based on a photo by Rudy Burckhardt. Six of them were installed in Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, above Jasper Johns’ Dymaxion Map. Four of them are visible above, in a photo taken during Warhol’s visit to the Expo with John & Dominique de Menil. The one on the lower right is now in the Tate Modern.

If the Thirteen Most Wanted Men censorship was really as concerned with vice, power, and the homosexual gaze as Meyer argues, then Warhol’s uncensorable Self-Portraits read like an act of defiance. For his 2nd World’s Fair, Warhol didn’t shrink from political conflict; he met it straight on and came out on top.

1 Update: I just came across a story by Lucy Sante about Thirteen Most Wanted, which he published in 2009. It is, I assume, a fictional encounter with a retired NYC policeman who had the idea for a Ten Most Wanted list stolen from him by a fellow cop, who became lovers with a young Warhol, and then years later, while guarding the World’s Fair, saw his Most Wanted Men idea stolen again by his ex. Hmm. I think someone had better talk to John Giorno.

Images And Ideas I’ve Been Thinking Of

So many projects, so many browser tabs, open for so many months, I’ve gotta clear some of these things out:

I’ve wanted to remake the lost/overpainted panels from Andy Warhol’s Thirteen Most-Wanted Men mural for the NY World’s Fair since the Destroyed Richter Paintings days, but now with the comprehensive-sounding show at the Queens Museum opening, I’ve probably got a week to do it. And process it. And put it behind me. Ah well. The show does sound good, though.

Not sure why it didn’t occur to me sooner, but the news this week that MoMA’s started the dismantling of the Folk Art Museum gave me a flash of inspiration: The Williams+Tsien Folk Table Collection. Turn each bronze alloy panel into a unique memento/tabletop. Maybe there’s enough material inside to use for legs, &c., too. I see a couple dozen dining tables, as many coffee/side tables, and a handful of console/sofa tables. An edition of up to 63. They’d be a stunning addition to the finest home, and quite the conversation piece.

Actually, the inspiration came from Chester Higgins Jr’s photo of Billie & Tod holding architectural fragments. The domestication of architecture.

Also from the Times: Fred Conrad’s great photo showing the use of photomurals to evoke/approximate historical spatial experience at the Jewish Museum’s “Other Primary Structures” show. It’s interesting that they’re angled and mounted on wall-sized panels, not stuck to the moulding-encumbered wall. Makes them a bit more exhibition design and a bit less exhibition, I suppose.

Richter tweeted this the other day, and it’s been nagging at me ever since:

Reproductions of ‘Aunt Marianne’ and ‘Mr Heyde’ are shown in the exhibition ‘Registered, Persecuted, Annihilated’. gerhard-richter.com/exhibitions/…

— Gerhard Richter (@gerhardrichter) April 1, 2014

the exhibition of reproductions of paintings, that is, not just paintings based on photographs. Also, of course, the show is at the world’s most intensely named museum, the Topography of Terror.

I’ve reached out to the Topographers, hoping to find out more about how paintings function in an exhibit like this, and how the decision was made to include them as reproductions. But so far I have received absolutely no response. But I did get some screencaps from a YouTube video of the opening, which I can’t find right now:

Hmm, actually the panels look like reproductions of pages of books, not of paintings. Simultaneously more and less interesting.

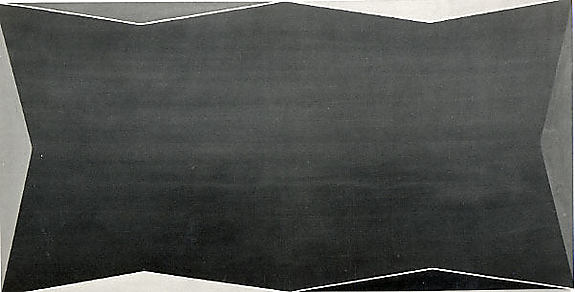

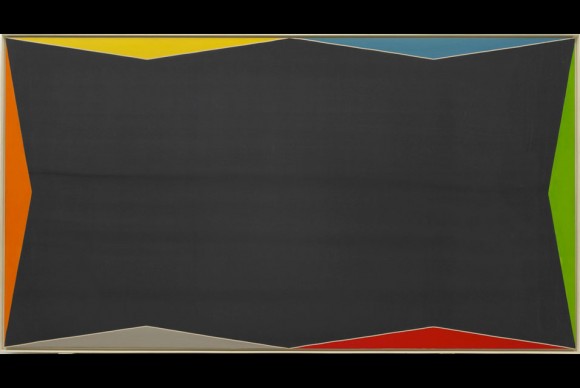

While rummaging around the Met’s collection database, looking for Arthur Vincent Tack info, I Google Imaged up this hard edge painting. Which apparently hadn’t been documented in the color photo era, but I couldn’t find it on the Met’s site.

As I was posting this I realized the filename is the accession number, 1978.565, Larry Zox. 1978’s obviously too old for Hard Edge; the painting’s from 1966, an at once unusual and logical size of 50×100 inches. Untitled (from the Double Gemini Series).

Turns out the Guggenheim has a very similar painting, Alto Velto, from 1969. Color really matters in these jpgs.

Martin Bromirski posted images from a 2008 Larry Zox show at Stephen Haller.

Para-Real Conversation Really Happening, Wed. Feb 5, 7PM At 601Artspace

Vic Muniz After Gerhard Richter (from pictures of color) (2001) and Greg Allen Destroyed Richter Painting No.2 (2012, left) and Destroyed Richter Painting No.4 (2012)

I’m really stoked to have the Destroyed Richter Paintings project included in “Para-Real,” an exhibition at 601Artspace, that has been extended until this weekend [closes Feb. 8, cf. Ken Johnson’s review in the NYTimes].

Magda Sawon curated the show with works from the 601 collection and others, and she paired Vik Muniz’s big paint chip Portrait of Betty with one of the Destroyed Richters. I’ve been a big fan of Muniz’s work for years and was particularly taken by his Pictures of Color series when we first saw them in Venice in August 2001. We barely knew how great we had it back then.

But anyway, that’s just one of many interesting pairings of works that examine notions of the real. If you haven’t seen the show already, I hope you’ll put it on your itinerary.

Maybe you should put it on your calendar tomorrow, in fact, say, 7pm, when our rescheduled conversation takes place with Robert Blake, Director of Special Projects at 601 Artspace, Jennifer & Kevin McCoy, John Powers and I. I’ve been looking forward to it for weeks. Months, even.

A round table conversation on Para-Real moderated by Robert Blake and led by Magdalena Sawon with Greg Allen, Jennifer and Kevin McCoy and John Powers

Wednesday, February 5, 2014, 7-8:30p [601artspace.org]

On Schwendener On Richard Serra & Public Art

I’m pleased to see some actual critical response to Richard Serra’s sculptures, and Martha Schwendener is more right than wrong in her review of Serra’s latest shows at Gagosian. But this retelling of the Tilted Arc controversy is based on several faulty premises that are amply documented and refuted in the written record of the case.

It’s hard to approach Mr. Serra’s sculptures without some kind of baggage. There is, of course, the unfortunate 1989 “Tilted Arc” episode, in which that commissioned sculpture by Mr. Serra was removed from Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan after complaints from neighbors and workers that it impinged on their use of Foley Square. In the aftermath of that fiasco, rather than fighting for the rights of artists creating public sculpture, Mr. Serra’s response was to make abstract drawings with puerile titles like “The United States Government Destroys Art” and “No Mandatory Patriotism,” both from 1989.

When exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2011, these drawings seemed only to iterate Mr. Serra’s myopic misunderstanding of art in the public realm. As the art historian Leo Steinberg put it, the space of Federal Plaza was Serra’s “raw material, but there are a thousand people working there, so this is not raw material but the space of their existence.”

The campaign against Tilted Arc was started by a judge in the building, and it became an ascendant conservative rally that pulled in the likes of Rudy Giuliani. Public opinion, even the opinion of the workers in the Federal Building was not opposed to the sculpture. The commission assembled to judge the work’s fate was stacked, and its recommendations went against the evidence it assembled.

What I bristle against most, I suppose, is Schwendener’s idea that Serra did not “fight for the rights of artists creating public sculpture.” That is exactly what he did when he sued the GSA to stop the removal of the work, and to declare it destroyed when it was removed. In the legal context of the time, this was, unfortunately, the most that could be done.

Of all artists, Serra has pushed the hardest for the primacy and autonomy of the artist’s vision. His take-it-or-leave-it stand is certainly annoying and abrasive to some people, but it is principled, and it is at the core of his practice, and apparently, his personality. He’s not a collaborative guy. He’s not a compromiser. He compared Robert Venturi’s plan for Pennsylvania Avenue to the Nazis. He walked out on Helmut Kohl and removed his name from the Berlin Holocaust Memorial rather than take the chancellor’s suggestions. [Schwendener mentions the memorial in her review, but ignores Serra’s involvement.] He apparently walked out on Steve Ratner when asked to pitch for a Hudson Yards public art project.

It may very well be the case that Serra is unsuited for public art and the political rigamarole that it requires. But he wasn’t poisoning the well so much as pissing on a reactionary fire that had already been lit during the Reagan Era. If such non-accommodationism is damaging to artists’ prospects for making public art, then maybe we should consider the processes by which public art comes to be. Maybe the gargantuan spatial spectacles Serra produces now really are optimized for private consumption, the single decisionmaker, the big checkwriter. But whatever Serra’s faults, the public art ecosystem in the US has rarely produced works that command such a spirited defense as Tilted Arc received back in the day.

Previously:

On those “Revenge Drawings”: Richard Serra was not pleased with the US Government

Serra interview from 1982: And I AM. An American Sculptor.

You really should have The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, the 1990 compendium of material from the case [amazon]

What Makes Today’s Amazon Chinese Paint Mill So Different, So Appealing?

Alright, I know it all looked like a black hole of boring embarrassment last week, but Amazon Art just broke through to the other side.

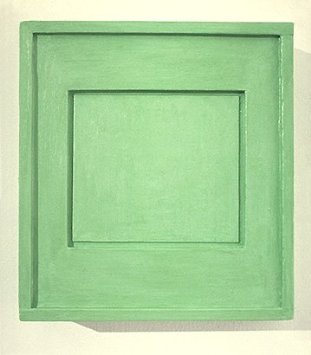

Artisoo Surrogate Painting [No. 783] – Oil painting reproduction 30” x 26” – Allan McCollum, $193

Kriston Capps and Joy Garnett were tweeting this link to what seems to be an Allan McCollum Surrogate Painting (No. 783), a 30×26-in original oil painting, offered on Amazon by a gallery called Artisoo–for $193. Kriston pointed out that Amazon’s gallery system has a forgery problem, or at least an authenticity problem. Which could very well be the case! But this is not why.

Because Allan McCollum’s Surrogate Paintings are not oil on canvas, but acrylic on plaster. Or as in the case of [No. 783], which was made in 1978, acrylic on wood. They’re painting-shaped sculptures, really. And what Artisoo is selling here is actually an original oil painting of the jpg reproduction of the McCollum. Artisoo is making an artwork that’s the picture of an artwork that the original artist hoped would help a gallery “become like a picture.”

Artisoo guarantees that your Surrogate Painting [No. 783] will be “100% hand-painted by our experienced artists. We stand by our top quality.” And you can order with confidence knowing that “The original motifs presented by Artisoo are created by artists from the most prestigious art schools and academies of fine arts. [emphasis added, because, ‘motifs’! -ed.]”

Chinese Paint Mill has appropriated Google Images and put it up for sale on Amazon. There are at least 18 other McCollum jpgs available as oil paintings. They all appear in the first page of the artist’s Google Image results. Artisoo currently offers 8,124 other paintings on Amazon, and unnumbered thousands more on their own website. In your choice of seven sizes.

It’s the fine art equivalent of LifeSphere, the Spamerican Apparel botcompany Babak Radboy wrote about that systematically turns every public domain image into every possible Zazzle product.

At least it’s trying to be. After a quick surf, I’d say that this Artisoo McCollum Surrogate Painting counts as a rare conceptual gem; easily 98% of the company’s merch is Chinese Paint Mill fluff. I’d call it pure over-the-sofa art, but that’d only account for one of the eight options in their Shop By Room function.

But there’s something sublime about the way a painting of a photograph of a minimalistic, monochromatic painted object encapsulates the entirety of orthodox post-war art history, collapses it, and drops it into the world’s biggest online vending machine. It’s painting pared down to its barest essence as a privileged cultural signifier: a decorative picture of whatever, made by hand. Painting sells its soul for Dino Sponges. But wait, there’s more!

Like any serious collector, I like to shop for my art alphabetically, which means the first post-war artist to emerge in Artisoo’s stable is Anne Truitt. Artisoo offers 62 paintings with an Anne Truitt “motif,” including installation shots of her trademark acrylic on poplar columns; monochromatic works on paper; sumi ink drawings; and even the barely visible washes of the Arundel paintings. Can’t wait to see how those come out.

Artisoo’s daring paintings, uh, interrogate the conventions of scale as deftly as the notion of medium, date, authorship, context, and form. At 30×10 inches, this painting of a Parva sculpture is easily three times the size of Truitt’s original.

Artisoo Signal – Oil painting reproduction 30” x 28” – Anne Truitt

In a move that feels appropriated from my own playbook, Artisoo even offers paintings of early works that Truitt destroyed, the aluminum sculptures she created in 1964 while living in Japan. Unlike Destroyed Richter Paintings, however, Artisoo’s Artisoo Signal – Oil painting reproduction 30” x 28” – Anne Truitt ($204) does not attempt to recreate the experience of being in the original’s presence; it promises only its own, bold self: a painting of a vintage Kodachrome of a nautically colored sculpture bathed in the light of Tokyo courtyard.

I’m on slow wireless at the moment, so I gave up hope of surfing through all 340 pages of Artisoo’s products, and instead started plugging in names of artists I liked, or rather, artists I’d like to see appropriated by Amazon Chinese Paint Mill. It didn’t really pan out. No Kosuth, no Andre, no Beuys, Lewitt, Gober, Sherman, Levine, Hesse, Newman or Prince, and no Richter. The company’s web-indexical curation strategy is clearly still a work in progress. There are several dozen Johnses on Artisoo.com, though. I wonder if I could order a copy of Flag in the exact dimensions of the Short Circuit original? Yes, there’s no Sturtevant.

Artisoo Abstract Painting – Oil painting reproduction 30” x 30” – Ad Reinhardt, $221

There are Alma Thomases, though. And 63 Calders. Would you like a painting of a stabile? Oh, nice, there are 50 Ad Reinhardts. Those ought to be interesting. Likewise the 23 Agnes Martins.

Artisoo Happy Valley – Oil painting reproduction 30” x 30” – Agnes Martin, $239

Here’s a standout, though, which reveals a lot about Artisoo’s practice. It’s a painting called, Http En Wikipedia Org Wiki File Hamilton Appealing2 Jpg 1956, and it comes 4x-36x larger than Richard Hamilton’s 10-inch paper collage.

Http En Wikipedia Org Wiki File Hamilton Appealing2 Jpg 1956 ($125-650)

Everything about Artisoo is so immediately and obviously fantastic, I almost don’t want to spoil it by seeing actual paintings. Almost.

Destroyed Agnes Martin Paintings

Untitled, 2004, Agnes Martin’s last painting. Image via Phaidon

The visits that maybe stick in the mind are the ones where she would show me four versions of a single painting and she’d say to me. ‘I think this is the best one, what do you think?’ Invariably there was so little difference between them, it was so hard to say, they were all really beautiful. And then she’d say OK we’re gonna keep that one and we’re going to cut up the others. And I would help with a knife slice up the paintings. Those are the studio visits that I think are the sharpest, helping her destroy the work.

What goes through your mind the first time you hear something like that?

It’s her work, and I’m a co-worker in the art field. . . but yeah. It is brutal. I was there at the end of her life and she said ‘go down to the studio, there are three paintings. Hanging on the wall is the one I want to keep, I want you to destroy the other two.’ So I went down to the studio. The two paintings she wanted me to destroy were magnificent – absolutely perfect. The one on the wall was a very stormy painting, unlike anything that she had made since the 60s. I certainly didn’t want to destroy those two spectacular paintings but I did. I sliced them to ribbons and put them in the trash. When I came back. She said, ‘did you do it?’ I said, ‘I did it.’ And that was that. Our last conversation.

Arne Glimcher, in a Q&A published last month by Phaidon.

The Q&A is timed to the publication of Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances by Arne Glimcher, an extraordinary collection of Martin’s writings and correspondence, many works, and Glimcher’s own snapshots and notes. He would take extensive notes during his studio visits with Martin in New Mexico, and then transcribe them on the plane home.

He expands on Martin’s last request to destroy some of her work in March 2004:

A mystique exists that Agnes painted very few works but in actuality, she painted almost daily when inspired and that was with some frequency. However, only a relatively small amount of works exist from such a long and productive life because she destroyed most of the works she produced. Probably no artist has ever been a better editor than Agnes Martin. The rejected paintings were shredded with a mat knife. As she grew older, during the last few years, she enlisted the help of friends (myself included) to destroy the unacceptable works, as it was very hard to cut through the thick primed linen fabric. When I once asked her why she was destroying a particularly delicate and beautiful work, she said, ‘It’s too aggressive, and there’s a mistake.’ Most often that referred to a pooling of colour in one of the works that made the brushstrokes discontinuous. The mistake became an unwanted ‘focus’ in a non-compositional painting, which disturbed its serenity.

Trumpet, 1967, an earlier last painting by Agnes Martin, image via zwirnerandwirth

I drove to the studio where I found three grey paintings, all of which were beautiful. Using her mat knife, I reluctantly shredded two and spared the one that hung on the wall. It was unique, expressionistically painted with stormy grey asymmetrical brushstrokes covering the surface. Five thin pencil lines visually grounded the passionate wash to the canvas. There is only one other painting with such an expressionistic asymmetrical handling of brush work. It is called Trumpet and was painted in 1967, just before she took her long hiatus and first departure from painting. On first glance, in this last painting, Agnes appears to have taken a new direction. Comparing Untitled (2004) with Trumpet, it is clear that it was not so much a change in style as it was coming full circle home.

[2016 UPDATE: In 2013 Glimcher spoke with Tate Modern curator Frances Morris about his memoir, and the last audience question was about what the last two destroyed paintings looked like:

The two that I had to destroy were very dissimilar from the one that was left, which you saw the picture of. They were much more rigorous; they were less emotional paintings. They looked more like the 70s than they did the 90s, or the late work. They seemed to be a little bit out of context, but perfect paintings, really exquisite paintings. So I took the box cutter and sliced them to ribbons.

]

In reviewing “Five Decades,” a 10-painting Zwirner & Wirth survey in 2003, Holland Cotter called the artist’s practice, “a kind of yoga of painting.” I’m still trying to think it through, and understand why she destroyed so much of her work–or her paintings, really, and maybe that’s the difference–but perhaps it involves a kind of yoga of looking as well.

Buy Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances by Arne Glimcher via Amazon [amazon]

Ten questions for Pace Gallery’s Arne Glimcher [phaidon via yhbhs]

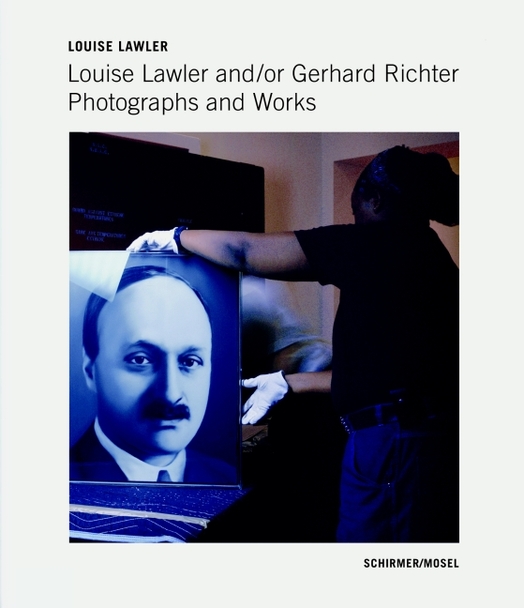

Deployed Gerhard Richter Paintings

Via the New Yorker’s photodesk, an excellent slideshow of a sampling of Louise Lawler’s photographs of artworks by Gerhard Richter, in situ and in transit.

My favorite is still the site-specifically distorted No Drones, which I posted about last winter. But for the newly published book, Louise Lawler and/or Gerhard Richter, Richter archivist Dietmar Elger looks to have stuck with each of the 29 photo’s original dimensions.

Interestingly, the US edition of the book has retitled its way out of the authorial ambiguity of the original: Louise Lawler: The Gerhard Richter Photographs.

Slide Show | Louise Lawler’s Gerhard Richter [newyorker via @janehu and @briansholis]

Previously:the disco ball next to the Lawler

About Destroyed Richter Paintings

Also: the crates for Richter’s 4,900 Colours are so sexy

Richteriana In The German News

There is a review of Richteriana in this week’s DER SPIEGEL [22/2012]. Google doesn’t do tone, so who really knows, but it sounds alright. There’s not a link or an English version of the Spiegel review yet, but I”ll add them as they appear.

It’s written by Ulrike Knoefel, the art critic whose article about “the separate and secret museum” of destroyed Gerhard Richter paintings provided the impetus [and imagery] for my paintings.

I like that she noted,

Der Hinweis darauf, dass die nicht mehr vorhandenen Richter-Gemälde heute viele Millionen wert wären, brachte Allen dazu aus seinem Werk über Richter auch ein Werk über den Kunstmarkt zu machen.

And of course, then there’s the part about how, “Letzlich hat er ebenfalls große Konzeptkunst geschaffen.”

Mhmm.

If I want my Konzeptkunst to be really große, I may have to go all in, and decide to destroy whichever of the Destroyed Richter Paintings the market doesn’t take. While supplies last.

Richteriana In The News

I find the maxim of not reading reviews of one’s work to be much easier to live by when there are no reviews.

Because at least two takes on Richteriana have already been published, and I like the concept. It’s reassuring but also a but unsettling. And then a little invigorating, to encounter other peoples’ takes on your ideas.

In the Village Voice, James Hannaham called the Destroyed Richter Paintings “outlandish,” which I took to be a good sign, even though I wouldn’t–you know what, no, let’s just let it hang out there:

While partially homage, this work invades the great man’s privacy on at least two levels: first, by showing us images he apparently didn’t want anyone to see, and second, by co-opting and outsourcing his technique.

While I don’t think that’s literally true, the invasion of privacy part, I do think Hannaham is right to find an uneasiness in the images, not just whether they should exist, but whether they do or don’t, and if so, how?

And also Jane Hu did a lot of context work on Richter, his art, his history, his control issues, and the larger Richter and Art Industrial Complexes themselves:

[T]he artist has destroyed or painted over many past works, in order, presumably, to maintain a narrative about his artistic trajectory that satisfies his present sense as a painter. Richter knows as well as anyone that art history traffics in selling a story, as much as it does in telling an image. While the first half of his career produced paintings that tried to approximate photographic realism, he later increasingly turned to abstraction. And in doing so, no matter what other aesthetic reasons he may have had, Richter not only has revised his own biography, but those of his paintings as well.

Her discussion of David Diao’s work Synecdoche, is particularly sharp. On its own, David’s painting is amazing, but his wresting control of a vintage Benjamin Buchloh Artforum exhibition catalogue [whoops, 2nd time I’ve made that mistake. -ed] essay is a blunt and powerful and unsettling gesture.

The more I look at Synecdoche, the more it feels like the most important argument in the show.

An Intentionally Incomplete Inventory of Pictures: Richter’s Bilderverzeichnis

Photograph of a painting destroyed by Gerhard Richter, Gerhard Richter Archiv via Spiegel

Since I first started looking into them, I’ve wanted to know why Gerhard Richter destroyed some of his paintings. Because, of course, some of them weren’t “destroyed” destroyed, but just painted over, with their previous state being technically defined as a momentary completion, not a work in process. There are only a few like that in the Catalogue Raisonné, though; most of the works listed as “Destroyed” are presumably actually destroyed.

But at least they all got Catalogue Raisonné numbers. Ulrike Knöfel wrote about a different category of destroyed Richters, largely undiscussed and unseen, which were destroyed before the artist began his catalogue raisonné, and which thus, with maybe one exception, don’t have a CR number, and are thus excluded from Richter’s declared oeuvre. Even if they were authentically created by Richter, and shown in exhibitions, and offered for sale.

As Dietmar Elger points out in his biography of Richter, A Life In Painting, Richter actually conceives of the Catalogue Raisonné as a work of art in itself, one which, like Atlas, is still in process.

I recently met with Dr. Elger during a trip to New York, and we spoke about these dynamics of creation, destruction, recognition, and archiving as they play out in Richter’s practice. Elger runs the Gerhard Richter Archiv at the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and maintains the Catalogue Raisonné, so he has a seat at the table for much of this history. After a brief fanboy prelude, in which he signed my book [and my copy of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres catalogue raisonne which he was also involved in], we got to talking. [We met for information, not as an actual interview, so I didn’t take notes or record our conversation, and I won’t directly attribute quotes, but just try to capture my recollections.]

Continue reading “An Intentionally Incomplete Inventory of Pictures: Richter’s Bilderverzeichnis”

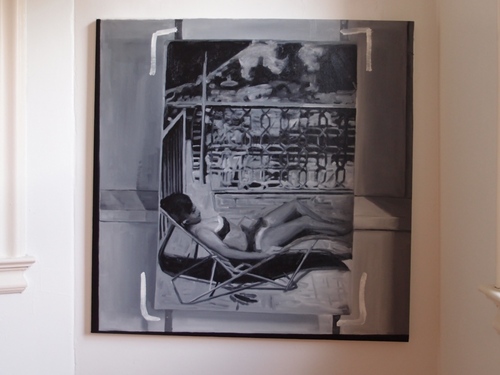

Will Work Off Jpegs: Destroyed Richter Paintings

Destroyed Richter Painting #03

First off, a huge thanks to everyone who came to the opening of Richteriana Saturday, and a high five to Magda, Postmasters and the artists in the show. It really does look great, and interesting, and provocative. If you can, you should definitely see it in person.

Destroyed Richter Painting #04

Which is actually one reason I debated not posting images of the Destroyed Richter Paintings paintings I put into the show. One of the real drivers of making the paintings was to approximate the experience of standing in front of paintings that could now only be seen through photos. Or transparencies. Or JPGs. And to measure what the difference is between these different modes of mediated perception.

Destroyed Richter Painting #02

I did not have access to the actual dimensions of Richter’s original works, but I worked hard to deduce the size as well as to approximate the image, so as to make the feeling of seeing a picture in person as authentic [sic] as possible, even while acknowledging that Richter made such an experience impossible.

Destroyed Richter Painting #05

But looking at jpgs of paintings [of jpgs of paintings of photos] obviously falls short of this idealized encounter. As so much of our art encounter/consumption does. It’s a distinction that most people miss or gloss over, but which is not lost on Tyler Green, who recently addressed the subject of critics reviewing shows they haven’t seen by tweeting, “I never ‘work’ off JPEG.”

Richter actually showed most or all of the paintings depicted here between 1964-67, so in a way, there’s an aspect of going back in time, to encounter Richter and his work at the beginning of his Western career. A time when the context of the work wasn’t hype and adulation and skyrocketing prices, but bafflement, resistance, and indignation. There are early photo paintings that survive only because someone bought them or kept them; so these works, which were once good enough to be exhibited or put on sale, were rejected by the market before they were ultimately rejected by the artist himself.

Destroyed Richter Painting #01

The one exception/mystery is Grau. This is one of the 70+ paintings that did make it into the catalogue raisonne, but which are now listed as destroyed. And if there’s a surviving image of the three destroyed grey monochromes [CR395-1-3], I couldn’t find it. So all that’s known publicly is the dimensions, and the unusual support [wood panel]. But that’s part of the beauty of the grey paintings, I thought, that you could think you could credibly extrapolate an actual painting from such minimal information. And seeing it in person really makes me miss Richter’s version–and to wonder what happened to it.